Franz Joseph I of Austria

| Franz Joseph I | |

|---|---|

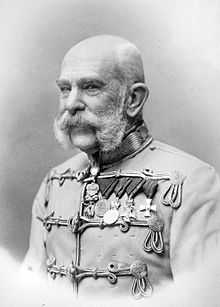

Franz Joseph in c. 1905 | |

| Emperor of Austria King of Hungary and Croatia King of Bohemia | |

| Reign |

2 December 1848 – 21 November 1916 |

| Predecessor | Ferdinand I |

| Successor | Charles I & IV |

| King of Lombardy–Venetia | |

| Reign |

2 December 1848 – 12 October 1866 |

| Predecessor | Ferdinand I |

| President of the German Confederation | |

| In office | 1 May 1850 – 24 August 1866 |

| Predecessor | Frederick William IV |

| Successor | William I |

| Spouse | Elisabeth of Bavaria |

| Issue |

Archduchess Sophie Archduchess Gisela Crown Prince Rudolf Archduchess Marie Valerie |

| House | House of Habsburg-Lorraine |

| Father | Archduke Franz Karl of Austria |

| Mother | Princess Sophie of Bavaria |

| Born |

18 August 1830 Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna |

| Died |

21 November 1916 (aged 86) Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna |

| Burial | Imperial Crypt |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Signature |

|

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (German: Franz Joseph I., Hungarian: I. Ferenc József, 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria and Apostolic King of Hungary from 1848 until his death in 1916. From 1 May 1850 until 24 August 1866 he was President of the German Confederation.[1]

In December 1848, Emperor Ferdinand abdicated the throne as part of Ministerpräsident Felix zu Schwarzenberg's plan to end the Revolutions of 1848 in Austria, which allowed Ferdinand's nephew Franz Joseph to ascend to the throne. The event took place in the Moravian city of Olomouc. Largely considered to be a reactionary, Franz Joseph spent his early reign resisting constitutionalism in his domains. The Austrian Empire was forced to cede most of its claim to Lombardy–Venetia to the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia following the conclusion of the Second Italian War of Independence in 1859, and the Third Italian War of Independence in 1866. Although Franz Joseph ceded no territory to the Kingdom of Prussia after the Austrian defeat in the Austro-Prussian War, the Peace of Prague (23 August 1866) settled the German question in favour of Prussia, which prevented the unification of Germany under the House of Habsburg (Großdeutsche Lösung).[2]

Franz Joseph was troubled by nationalism during his entire reign. He concluded the Ausgleich of 1867, which granted greater autonomy to Hungary, hence transforming the Austrian Empire into the Austro-Hungarian Empire under his dual monarchy. His domains were then ruled peacefully for the next 45 years, although Franz Joseph personally suffered the tragedies of the execution of his brother, Maximilian in 1867, the suicide of his son, Crown Prince Rudolf in 1889, and the assassination of his wife, Empress Elisabeth in 1898.

After the Austro-Prussian War, Austria-Hungary turned its attention to the Balkans, which was a hotspot of international tension due to conflicting interests with the Russian Empire. The Bosnian crisis was a result of Franz Joseph's annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908, which had been occupied by his troops since the Congress of Berlin (1878). On 28 June 1914, the assassination of the heir-presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne, his nephew Archduke Franz Ferdinand, at the hands of Gavrilo Princip, a Serbian nationalist, resulted in Austria-Hungary's declaration of war against the Kingdom of Serbia, which was Russia's ally. This activated a system of alliances which resulted in World War I.

Franz Joseph died on 21 November 1916, after ruling his domains for almost 68 years. He was succeeded by his grandnephew Charles. He was the longest-reigning emperor of Austria.

Name

His name in German was Franz Joseph I and in Hungarian was I. Ferenc József. His names in other languages were:

- Romanian: Francisc Iosif (no number used)

- Croatian and Bosnian: Franjo Josip I.

- Serbian: Фрања Јосиф (no number used)

- Slovene: Franc Jožef I.

- Czech: František Josef I.

- Slovak: František Jozef I.

- Italian: Francesco Giuseppe I.

Early life

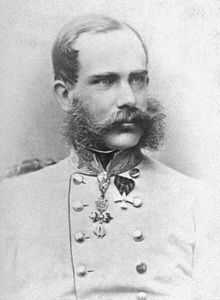

.jpg)

Franz Joseph was born in the Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, the oldest son of Archduke Franz Karl (the younger son of Holy Roman Emperor Francis II), and his wife Princess Sophie of Bavaria. Because his uncle, from 1835 the Emperor Ferdinand, was weak-minded, and his father unambitious and retiring, the young Archduke "Franzl" was brought up by his mother as a future Emperor with emphasis on devotion, responsibility and diligence. Franzl came to idolise his grandfather, der Gute Kaiser Franz, who had died shortly before the former's fifth birthday, as the ideal monarch. At the age of 13, young Archduke Franz started a career as a colonel in the Austrian army. From that point onward, his fashion was dictated by army style and for the rest of his life he normally wore the uniform of a military officer.[3]

Franz Joseph was soon joined by three younger brothers: Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian (born 1832, the future Emperor Maximilian of Mexico); Archduke Karl Ludwig (born 1833, and the father of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria), and Archduke Ludwig Viktor (born 1842), and a sister, Maria Anna (born 1835), who died at the age of four.[4]

Following the resignation of the Chancellor Prince Metternich during the Revolutions of 1848, the young Archduke, who it was widely expected would soon succeed his uncle on the throne, was appointed Governor of Bohemia on 6 April, but never took up the post. Instead, Franz was sent to the front in Italy, joining Field Marshal Radetzky on campaign on 29 April, receiving his baptism of fire on 5 May at Santa Lucia. By all accounts he handled his first military experience calmly and with dignity. Around the same time, the Imperial Family was fleeing revolutionary Vienna for the calmer setting of Innsbruck, in Tyrol. Soon, the Archduke was called back from Italy, joining the rest of his family at Innsbruck by mid-June. It was at Innsbruck at this time that Franz Joseph first met his cousin Elisabeth, his future bride, then a girl of ten, but apparently the meeting made little impact.[5]

Following victory over the Italians at Custoza in late July, the court felt safe to return to Vienna, and Franz Joseph travelled with them. But within a few months Vienna again appeared unsafe, and in September the court left again, this time for Olmütz in Moravia. By now, Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz, the influential military commander in Bohemia, was determined to see the young Archduke soon put onto the throne. It was thought that a new ruler would not be bound by the oaths to respect constitutional government to which Ferdinand had been forced to agree, and that it was necessary to find a young, energetic emperor to replace the kindly, but mentally unfit Emperor.[6]

It was thus at Olmütz on 2 December that, by the abdication of his uncle Ferdinand and the renunciation of his father, the mild-mannered Franz Karl, Franz Joseph succeeded as Emperor of Austria. It was at this time that he first became known by his second as well as his first Christian name. The name "Franz Joseph" was chosen deliberately to bring back memories of the new Emperor's great-granduncle, Emperor Joseph II, remembered as a modernising reformer.[7]

Domestic policy

Under the guidance of the new prime minister Prince Schwarzenberg, the new emperor at first pursued a cautious course, granting a constitution in early 1849. At the same time, military campaigns were necessary against the Hungarians, who had rebelled against Habsburg central authority under the name of their ancient liberties. Franz Joseph was also almost immediately faced with a renewal of the fighting in Italy, with King Charles Albert of Sardinia taking advantage of setbacks in Hungary to resume the war in March 1849. Soon, though, the military tide began to turn in favor of Franz Joseph and the Austrian whitecoats. Almost immediately, Charles Albert was decisively beaten by Radetzky at Novara, and forced both to sue for peace and to abdicate his throne. In Hungary, the situation was more grave and Austrian defeat was quite possible. Sensing a need to secure his right to rule, he sought help from Russia, requesting the intervention of Tsar Nicholas I, in order "to prevent the Hungarian insurrection developing into a European calamity."[8] Russian troops entered Hungary in support of the Austrians and the revolution was crushed by late summer of 1849. With order now restored throughout the Empire, Franz Joseph felt free to go back on the constitutional concessions he had made, especially as the Austrian parliament, meeting at Kremsier, had behaved, in the young Emperor's view, abominably. The 1849 constitution was suspended, and a policy of absolutist centralism was established, guided by the Minister of the Interior, Alexander Bach.[9]

The next few years saw the seeming recovery of Austria's position on the international scene following the near disasters of 1848–1849. Under Schwarzenberg's guidance, Austria was able to stymie Prussian scheming to create a new German Federation under Prussian leadership, excluding Austria. After Schwarzenberg's premature death in 1852, he could not be replaced by statesmen of equal stature, and the Emperor effectively took over himself as prime minister.[9]

Assassination attempt in 1853

On 18 February 1853, the Emperor survived an assassination attempt by Hungarian nationalist János Libényi.[10] The emperor was taking a stroll with one of his officers, Maximilian Karl Lamoral O'Donnell, on a city-bastion, when Libényi approached him. He immediately struck the emperor from behind with a knife straight at the neck. Franz Joseph almost always wore a uniform, which had a high collar that almost completely enclosed the neck. The collars of uniforms at that time were made from very sturdy material exactly to counter this kind of attack. Even though the Emperor was wounded and bleeding, the collar saved his life. Count O'Donnell (descendant of the Irish noble dynasty O'Donnell of Tyrconnell[11]) struck Libényi down with his sabre.[10]

O'Donnell, hitherto only a Count by virtue of his Irish nobility, was thereafter made a Count of the Habsburg Empire, conferred with the Commander's Cross of the Royal Order of Leopold, and his customary O'Donnell arms were augmented by the initials and shield of the ducal House of Austria, with additionally the double-headed eagle of the Empire. These arms are emblazoned on the portico of no. 2 Mirabel Platz in Salzburg, where O'Donnell built his residence thereafter. Another witness who happened to be nearby, the butcher Joseph Ettenreich, quickly overwhelmed Libényi. For his deed he was later elevated to nobility by the Emperor and became Joseph von Ettenreich. Libényi was subsequently put on trial and condemned to death for attempted regicide. He was executed on the Simmeringer Heide.

After this unsuccessful attack, the Emperor's brother Ferdinand Maximilian Joseph, later Emperor of Mexico, called upon Europe's royal families for donations to a new church on the site of the attack. The church was to be a votive offering for the survival of the Emperor. It is located on Ringstraße in the district of Alsergrund close to the University of Vienna, and is known as the Votivkirche.[10]

Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867

The 1850s witnessed several failures of Austrian external policy: the Crimean War and break-up with Russia, and defeat in the Second Italian War of Independence. The setbacks continued in the 1860s with defeat in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, which resulted in the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867.[12]

Political difficulties in Austria mounted continuously through the late 1800s and into the 20th century. But Franz Joseph remained immensely respected. His patriarchal authority held the Empire together while the politicians squabbled.[13]

Foreign policy

The German question

The main foreign policy goal of Franz Joseph I had been the unification of Germany under the House of Habsburg.[14] This was justified on grounds of precedence; from 1452 to the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, with only one period of interruption under the Wittelsbachs, the Habsburgs had generally held the German crown.[15] However, Franz Joseph's desire to retain the non-German territories of the Habsburg Austrian Empire in the event of German unification proved problematic. There quickly developed two factions, one party of German intellectuals favouring a Greater Germany under the House of Habsburg; the others favouring a Lesser Germany. The Greater Germans favoured the inclusion of Austria in a new all-German state on the grounds that Austria (Österreich) had always been a part of Germanic empires, that it was the leading power of the German Confederation, and that it would be absurd to exclude eight million Austrian Germans from an all-German nation state. The champions of a lesser Germany argued against the inclusion of Austria on the grounds that it was a multination state, not a German one, and that its inclusion would bring millions of non-Germans into the German nation state.[16] If Greater Germany was to prevail, the crown would necessarily have to go to Franz Joseph, who had no desire to cede it in the first place to anyone else.[16] On the other hand, if the idea of a smaller Germany won out, the German crown could of course not possibly go the Emperor of Austria, but would naturally be offered to the head of the largest and most powerful German state outside of Austria–the King of Prussia. The contest between the two ideas thus quickly developed into a contest between Austria and Prussia. After Prussia decisively won the Seven Weeks war, this question was solved; Austria lost no territories as long as they remained out of German affairs.[16]

The Three Emperors League

In 1873, two years after the unification of Germany, Franz Joseph entered into the League of Three Emperors with Kaiser Wilhelm I of Germany and Tsar Alexander II of Russia (who was succeeded by Tsar Alexander III in 1881). The league had been designed by the German chancellor Otto von Bismarck, as an attempt to maintain the peace of Europe. It would last intermittently until 1887.

The Czech Question

Many Czech people were waiting for political changes in monarchy, including Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk and others. Masaryk served in the Reichsrat (Austrian Parliament) from 1891 to 1893 in the Young Czech Party and again from 1907 to 1914 in the Realist Party (which he founded in 1900), but he did not campaign for the independence of Czechs and Slovaks from Austria-Hungary. In 1909 he helped Hinko Hinković in Vienna in the defense during the fabricated trial against mostly prominent Croats and Serbs, members of the Croato-Serb Coalition (such as Frano Supilo and Svetozar Pribićević), and others, who were sentenced to more than 150 years and a number of death penalties. The Czech question was not solved during all Franz Joseph's political career.

The Vatican

In 1903, Franz Joseph's veto of Cardinal Rampolla's election to the papacy was transmitted to the conclave by Cardinal Jan Puzyna. It was the last use of such a veto, because new Pope Pius X provided penalties for such.[17][18]

Bosnia and Herzegovina

The mid 1870's witnessed a series of violent rebellions against Ottoman rule in the Balkans, and equally violent and repressive responses from the Turks. The Russian Tsar, Alexander II, wanting to intervene against the Ottomans, sought and obtained an agreement with Austria-Hungary. In the Budapest Conventions of 1877, the two powers agreed that Russia would annex Bessarabia, and Austria Hungary would observe a benevolent neutrality toward Russia in the pending war with the Turks. As compensation for this support, Russia agreed to Austria-Hungary's annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina.[19] A scant 15 months later, the Russians imposed the Treaty of San Stefano on the Ottomans, which reneged on the Budapest accord and declared that Bosnia-Herzogovina would be jointly occupied by Russian and Austrian troops.[20] The treaty of San Stefano was overturned by the 1878 Treaty of Berlin. which allowed for sole Austrian occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, but did not specify a final disposition of the provinces. This omission was addressed in the Three Emperors' League treaty of 1881, where both Germany and Russia endorsed Austria's right to annex Bosnia-Herzegovina[21] However, by 1897, under a new Tsar, the Russian Imperial government had managed, again, to withdraw its support for Austrian annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina. The Russian Foreign minister, Count Michael Muraviev, stated that an Austrian annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina would raise "an extensive question requiring special scrutiny".[22]

In 1908, the Russian foreign minister, Alexander Izvolsky again, and for the third time, offered Russian support for the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina by Austria-Hungary, in exchange for Austrian support for the opening of the Bosporus Strait and the Dardanelles to Russian warships. The Austria's foreign minister, Alois von Aehrenthal, pursued this offer vigorously, resulting in the quid pro quo understanding with Izvolsky, reached on the 16th of September 1908, at the Buchlau Conference. However, Izvolsky made this agreement with Aehrenthal, without the knowledge of Tsar Nicholas II, his government in St. Petersburg, nor any of the other foreign powers including Britain, France and Serbia.

Based upon the assurances of the Buchlau Conference, not to mention the preceding treaties, Franz Joseph signed the proclamation announcing the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina into the empire on 6 October 1908. However, a diplomatic crisis erupted, as both the Serbs, and, incomprehensibly, the Italians, demanded compensation for the annexation, which the Austrian-Hungarian government would not entertain. The matter was not resolved until the revision of the Treaty of Berlin in April 1909. The incident served to exacerbate tensions between Austria-Hungary and the Serbs.

Outbreak of World War I

After the death of Crown Prince Rudolf, Franz Joseph's nephew, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, became heir to the throne. On 28 June 1914, Franz Ferdinand and his morganatic wife, Countess Sophie Chotek, were assassinated on a visit to Sarajevo. When he heard the news of the assassination, Franz Joseph said that "one has not to defy the Almighty. In this manner a superior power has restored that order which I unfortunately was unable to maintain."[23]

While the emperor was shaken, and interrupted his vacation in order to return to Vienna, he soon resumed his vacation to his imperial villa at Bad Ischl. With the emperor five hours away from the capital, most of the decision-making during the "July Crisis" fell to Count Leopold Berchtold, the Austrian foreign minister, Count Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, the chief of staff for the Austrian army, and the rest of the ministers.[24] On 21 July, Franz Joseph was apparently surprised by the severity of the ultimatum that was to be sent to the Serbs, and expressed his concerns that Russia would be unwilling to stand idly by, yet he nevertheless chose to not question Berchtold's judgment.[25] A week after the ultimatum, on 28 July, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, and two days later, the Austro-Hungarians and the Russians went to war. Within weeks, the French and British entered the fray. Because of his age, Franz Joseph was unable to take as much as an active part in the war in comparison to past conflicts.[26]

Death

Franz Joseph died in the Schönbrunn Palace on the evening of 21 November 1916, aged 86, during World War I. His death was a result of him developing pneumonia of the right lung several days after catching a cold while he was walking in Schonbrunn Park with the King of Bavaria.[27] He was succeeded by his grand-nephew Karl. But two years later, after the defeat in World War I, the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy was dissolved.[28]

His 67-year reign is the third-longest in the recorded history of Europe (after those of Louis XIV of France and Johann II, Prince of Liechtenstein).[29]

He is buried in the Kaisergruft in Vienna, where flowers are still left by monarchists.

Family

It was generally felt in the court that the Emperor should marry and produce heirs as soon as possible. Various potential brides were considered: Princess Elisabeth of Modena, Princess Anna of Prussia and Princess Sidonia of Saxony.[30] Although in public life the Emperor was the unquestioned director of affairs, in his private life his formidable mother still had a crucial influence. She wanted to strengthen the relationship between the Houses of Habsburg and Wittelsbach, descending from the latter house herself, and hoped to match Franz Joseph with her sister Ludovika's eldest daughter, Helene ("Nené"), four years the Emperor's junior. However, the Emperor became besotted with Nené's younger sister, Elisabeth ("Sisi"), a girl of sixteen, and insisted on marrying her instead. Sophie acquiesced, despite some misgivings about Sisi's appropriateness as an imperial consort, and the young couple were married on 24 April 1854 in St. Augustine's Church, Vienna.[31]

Their married life was not happy. Sisi never really adapted herself to the court and always had disagreements with the imperial family; their first daughter Sophie died as an infant; and their only son, Crown Prince Rudolf, died by suicide in 1889, in the infamous Mayerling Incident.[17]

In 1885 Franz Joseph met Katharina Schratt, a leading actress of the Vienna stage, and she became his friend and confidante. This relationship lasted the rest of his life, and was, to a certain degree, tolerated by Sisi. Franz Joseph built Villa Schratt in Bad Ischl for her, and also provided her with a small palace in Vienna.[32] Though their relationship lasted 34 years, it remained platonic.[33]

The Empress was an inveterate traveller, horsewoman, and fashion maven who was rarely seen in Vienna. She was stabbed to death by an Italian anarchist in 1898 while on a visit to Geneva; Franz Joseph never fully recovered from the loss. According to the future empress Zita of Bourbon-Parma he usually told his relatives: "You'll never know how important she was to me" or, according to some sources, "You will never know how much I loved this woman." (although there is no definite proof he actually said this).[34]

Relationship with Franz Ferdinand

With Rudolf's death, Archduke Franz Ferdinand became heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary. The aging emperor, Franz Joseph, had a fairly contentious relationship with his nephew, however. He had never been a favorite nephew of the emperor. Franz Ferdinand had earned the ire of Franz Joseph in declaring his desire to marry Sophie Chotek, a marriage that was out of the question in the mind of the emperor, as Chotek was merely a countess, as opposed to being of royal or imperial blood. Despite the fact that the emperor was receiving letters from members of the imperial family throughout the fall and winter of 1899, Franz Joseph stood his ground.[35] Franz Joseph finally consented to the marriage in 1900. However, the marriage was to be morganatic and any children that they were to have would be ineligible to succeed to the throne.[36] The couple were married on 1 July 1900. The emperor did not attend the wedding, nor did any of the archdukes. After that, the two men disliked and distrusted each other.[32]

Following the assassination of Franz Ferdinand and Sophie in 1914, Franz Joseph's daughter, Marie Valerie noted that her father expressed his greater confidence in his new heir presumptive, his great-nephew, Archduke Karl.[37] The emperor admitted to his daughter, regarding the assassination, that, "for me, it is a relief from a great worry."[37]

Issue

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Duchess Elisabeth in Bavaria (24 December 1837 – 10 September 1898; married on 24 April 1854 in St. Augustine's Church, Vienna) | |||

| Sophie Friederike Dorothea Maria Josepha | 5 March 1855 | 29 May 1857 | died in childhood |

| Gisela Louise Marie | 15 July 1856 | 27 July 1932 | married, 1873 her second cousin, Prince Leopold of Bavaria; had issue |

| Rudolf Francis Charles Joseph | 21 August 1858 | 30 January 1889 | died in the Mayerling Incident married, 1881, Princess Stephanie of Belgium; had issue |

| Marie Valerie Mathilde Amalie | 22 April 1868 | 6 September 1924 | married, 1890 her second cousin, Archduke Franz Salvator, Prince of Tuscany; had issue |

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Franz Joseph I of Austria | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Orders, decorations, and honours

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Austrian decorations

Emperor Franz Joseph was Grand Master of the following chivalric orders:

- Order of the Golden Fleece (ex officio as Emperor of Austria)

- Military Order of Maria Theresa (Militär Maria-Theresien-Orden, ex officio as Emperor of Austria)

- Royal Hungarian Order of Saint Stephen (Königlich ungarischer St. Stephan-Orden, ex officio as Emperor of Austria)

- Order of Leopold (Leopold-Orden, ex officio as Emperor of Austria)

- Order of the Iron Crown (Orden der Eisernen Krone, ex officio as Emperor of Austria)

- Imperial Order of Franz Joseph

- Order of Elizabeth

He was awarded the following military medals:

- War Medal

- Cross of Honour for 50 years of military service

- Military Cross for the 60th year of the reign

Franz Joseph founded the Order of Franz Joseph (Franz Joseph-Orden), 1849, and the Order of Elizabeth (Elizabeth-Orden), 1898.

- Foreign decorations

- Order of Milosh the Great, Kingdom of Serbia

- Knight of the Supreme Order of the Order of the Most Holy Annunciation (Kingdom of Italy) – 1869

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus (Kingdom of Italy) – 1869

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown of Italy (Kingdom of Italy) – 1869

- Knight of the Order of the Garter (United Kingdom) – 1867 (Expelled in 1915)

- Royal Victorian Chain (UK) (Expelled in 1915) - 1904

- Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order (United Kingdom) (Expelled in 1915)

- Knight Grand Cross of the Military Order of Max Joseph (Bavaria)

- Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle (Prussia)

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Red Eagle (Prussia)

- Pour le Mérite ("Blue Max", Prussia)

- Knight Grand Cross of the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern (German Empire)

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Prince Danilo I (Montenegro)

- Knight Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order (Grand Duchy of Hesse)

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Norwegian Lion (Norway)

- Knight Grand Cross of the Military Order of St. Henry (Saxony)

- Knight of the Order of Saints Cyril and Methodius (Kingdom of Bulgaria)

- Knight of the Order of St. Andrew (Russian Empire)

- Imperial Order of St. George, 4th class (Russian Empire)

- Bailiff of Honour and Devotion of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta

- Knight Grand Cross of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre (Vatican)

- Senator Grand Cross with Necklace of the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George (6 September 1849, Duchy of Parma)

- Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Order of Kamehameha I (Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, 1865)

- Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the Royal Order of Kalākaua (Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, 1878)

- Honorary appointments

- Colonel-in-chief, 1st (The King's) Dragoon Guards, British Army, 25 March 1896 – 1914

- Colonel-in-chief, Kexholm Life Guards Grenadier Regiment, Russian Army, until 26 June 1914

- Colonel-in-chief, 12th Belgorod Lancer Regiment, Russian Army, until 26 June 1914

- Colonel-in-chief, 16th (Schleswig-Holstein) Hussars, German Army

- Colonel-in-chief, 122nd (Emperor Francis Joseph of Austria, King of Hungary (4th Württemberg) Fusiliers

- Field Marshal, British Army, 1 September 1903 – 1914

Legacy

The archipelago Franz Josef Land in the Russian high Arctic was named in his honor in 1873. Franz Josef Glacier in New Zealand's South Island bears his name.

Franz Joseph founded in 1872 the Franz Joseph University (Hungarian: Ferenc József Tudományegyetem, Romanian: Universitatea Francisc Iosif) in the city of Cluj-Napoca (at that time a part of Austria-Hungary under the name of Kolozsvár). The university was moved to Szeged after Cluj became a part of Romania, becoming the University of Szeged.

In certain areas, celebrations are still being held in remembrance of Franz Joseph's birthday. The Mitteleuropean People's Festival takes place every year around 18 August, and is a "spontaneous, traditional and brotherly meeting among peoples of the Central-European Countries[38] ". The event includes ceremonies, meetings, music, songs, dances, wine and food tasting, and traditional costumes and folklore from Mitteleuropa.

| Monarchical styles of Franz Joseph I of Austria-Hungary | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty |

| Alternative style | My Lord |

| Monarchical styles of Franz Joseph I of Austria | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) | |

| Reference style | His Imperial Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Imperial Majesty |

| Alternative style | My Lord |

| Monarchical styles of Franz Joseph I of Hungary | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Apostolic Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Apostolic Majesty |

| Alternative style | My Lord |

Official Grand Title

His Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty,

Franz Joseph I, by the Grace of God Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, Bohemia, King of Lombardy and Venice, of Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia, Galicia, Lodomeria and Illyria; King of Jerusalem etc., Archduke of Austria; Grand Duke of Tuscany and Cracow, Duke of Lorraine, of Salzburg, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola and of the Bukovina; Grand Prince of Transylvania; Margrave of Moravia; Duke of Upper and Lower Silesia, of Modena, Parma, Piacenza and Guastalla, of Auschwitz, Zator and Teschen, Friuli, Ragusa (Dubrovnik) and Zara (Zadar); Princely Count of Habsburg and Tyrol, of Kyburg, Gorizia and Gradisca; Prince of Trent (Trento) and Brixen; Margrave of Upper and Lower Lusatia and in Istria; Count of Hohenems, Feldkirch, Bregenz, Sonnenberg, etc.; Lord of Trieste, of Cattaro (Kotor), and over the Windic march..[39]

After 1867:

His Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty,

Francis Joseph I, by the grace of God Emperor of Austria; Apostolic King of Hungary, King of Bohemia, Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia, Galicia, Lodomeria, Illyria; King of Jerusalem, etc.; Archduke of Austria; Grand Duke of Tuscany, Crakow; Duke of Lorraine, Salzburg, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, the Bukovina; Grand Prince of Transylvania; Margrave of Moravia; Duke of the Upper & Lower Silesia, Modena, Parma, Piacenza, Guastalla, Oswiecin, Zator, Cieszyn, Friuli, Ragusa, Zara; Princely Count of Habsburg, Tyrol, Kyburg, Gorizia, Gradisca; Prince of Trent, Brixen; Margrave of the Upper & Lower Lusatia, in Istria; Count of Hohenems, Feldkirch, Bregenz, Sonnenberg, etc.; Lord of Triest, Kotor, the Wendish March; Grand Voivode of the Voivodship of Serbia etc. etc..

Personal motto

- "mit vereinten Kräften" (German) = "Viribus Unitis" (Latin) = "With united forces" (as the Emperor of Austria). A homonymous war ship existed.

- "Bizalmam az Ősi Erényben" (Hungarian) = "Virtutis Confido" (Latin) = "My trust in [the ancient] virtue" (as the Apostolic King of Hungary)

In popular culture

- Franz Joseph is a character in both the 1930 operetta/musical The White Horse Inn (in German: Im weißen Rößl) and the Danish 1964 film (inspired by the operetta/musical) Summer in Tyrol (in Danish: Sommer i Tyrol), starring actor Peter Malberg as the Emperor in the latter.

- In the 1974 BBC miniseries Fall of Eagles, he was played by Miles Anderson as a young man and by Laurence Naismith in old age.

- In Kronprinz Rudolf (2006) (TV Movie) aka "The Crown Prince", a retelling of the tragic love affair between Austrian Archduke Rudolf, the only son of the aging Emperor, and Baroness Mary Vetsera, in which Franz Joseph I is played by Klaus Maria Brandauer.

- Franz Joseph I is seen as part of a Tom and Jerry cartoon episode in which the cat and mouse duo are set in c. 1890's Vienna. Word of their accidental yet successful cooperation in piano play receives the attention of the public and high Imperial officials, eventually leading to 'the Emperor himself!', who then organizes a royal command concert, mimicking the famous concert Empress Maria Theresa once arranged for child prodigy Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in 1762.

- He also occures as one of the historical cameos in novel Signum laudis (1988) written by Czech writer Vladimír Kalina.

See also

- Family tree of the German monarchs – he was related to every other ruler of Germany.

- List of coupled cousins

- Franc Jozeph Island, island in Albania in honor of the Emperor.

References

- ↑ Francis Joseph, in Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 19 April 2009

- ↑ "Gale Encyclopedia of Biography: ''Francis Joseph''". Answers.com. Retrieved 2013-12-02.

- ↑ Murad 1968, p. 61.

- ↑ Murad 1968, p. 101.

- ↑ Murad 1968, p. 33.

- ↑ Murad 1968, p. 8.

- ↑ Murad 1968, p. 6.

- ↑ Rothenburg, G. The Army of Francis Joseph. West Lafayette, Purdue University Press, 1976. p. 35.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Murad 1968, p. 41.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Murad 1968, p. 42.

- ↑ O'Domhnaill Abu – O'Donnell Clan Newsletter no. 7, Spring 1987 (ISSN 0790-7389))

- ↑ Murad 1968, p. 169.

- ↑

- William M. Johnston, The Austrian Mind: An Intellectual and Social History, 1848–1938 (University of California Press, 1983), p. 38

- ↑ Murad 1968, p. 149.

- ↑ Murad 1968, p. 150.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Murad 1968, p. 151.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Murad 1968, p. 127.

- ↑ See also http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05677b.htm (discussing the papal veto from the perspective of the Catholic Church)

- ↑ Albertini, Luigi (2005). The Origins of the War of 1914. New York, NY: Enigma Books. p. 16.

- ↑ Albertini, Luigi (2005). The Origins of the War of 1914. New York, NY: Enigma Books. p. 16.

- ↑ Albertini, Luigi (2005). The Origins of the War of 1914. New York, NY: Enigma Books. p. 37.

- ↑ Albertini, Luigi (2005). The Origins of the War of 1914. New York, NY: Enigma Books. p. 94.

- ↑ ↑ Albert Freiherr von Margutti: Vom alten Kaiser. Leipzig & Wien 1921, S. 147f. Zitiert nach Erika Bestenreiter: Franz Ferdinand und Sophie von Hohenberg. München (Piper), 2004, S. 247

- ↑ Palmer, Alan Twighlight of the Habsburgs: the Life and Times of Emperor Francis Joseph (Atlantic Monthly Press, 1994) pg. 328

- ↑ Palmer, pg. 330

- ↑ Palmer pgs. 332 & 333

- ↑ "Sausalito News 25 November 1916 — California Digital Newspaper Collection". Cdnc.ucr.edu. 1916-11-25. Retrieved 2013-12-02.

- ↑ Norman Davies, Europe: A history p. 687

- ↑ Murad 1968, p. 1.

- ↑ Twilight of the Habsburgs: The Life and Times of Emperor Francis Joseph By Alan Palmer

- ↑ Murad 1968, p. 242.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Murad 1968, p. 120.

- ↑ Morton, Frederic (1989). Thunder at Twilight: Vienna 1913/1914. pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Murad 1968, p. 117.

- ↑ Palmer, pg. 288

- ↑ Palmer, pg. 289

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Palmer, pg. 324

- ↑ Associazione Culturale Mitteleuropa. Retrieved 21 April 2012

- ↑ The official title of the ruler of Austrian Empire and later the Austria-Hungary had been changed several times: by a patent from 1 August 1804, by a court office decree from 22 August 1836, by an imperial court ministry decree from 6 January 1867 and finally by a letter from 12 December 1867. Shorter versions were recommended for official documents and international treaties: "Emperor of Austria, King of Bohemia etc. and Apostolic King of Hungary", "Emperor of Austria and Apostolic King of Hungary", "His Majesty Emperor and King" and "His Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty". The term Kaiserlich und königlich (K.u.K.) was decreed in a letter from 17 October 1889 for the military, the navy and the institutions shared by both parts of the monarchy.

From the Otto's encyclopedia (published during 1888–1909), subject 'King', online in Czech.

Bibliography

- Anatol Murad (1968). Franz Joseph I of Austria and his Empire. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8290-0172-3.

Further reading

- Bagger, Eugene Szekeres (1927). Francis Joseph: Emperor of Austria--king of Hungary. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons.

- Beller, Steven. Francis Joseph. Profiles in power. London: Longman, 1996. ISBN 0582060907

- Bled, Jean-Paul. Franz Joseph. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992. ISBN 0631167781

- Cunliffe-Owen, Marguerite. Keystone of Empire: Francis Joseph of Austria. New York: Harper, 1903.

- Gerö, András. Emperor Francis Joseph: King of the Hungarians. Boulder, Colo.: Social Science Monographs, 2001.

- Owens, Karen. Franz Joseph and Elisabeth The Last Great Monarchs of Austria-Hungary. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2013. . ISBN 9781476612164

- Palmer, Alan. Twilight of the Habsburgs: The Life and Times of Emperor Francis Joseph. New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1995. ISBN 0871136651

- Redlich, Joseph. Emperor Francis Joseph Of Austria. New York: Macmillan, 1929.

- Unterreiner, Katrin. Emperor Franz Joseph, 1830-1916: Myth and Truth. Wien: C. Brandstätter, 2006. ISBN 3902510447

- Van der Kiste, John. Emperor Francis Joseph: Life, Death and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire. Stroud, England: Sutton, 2005.

- Winkelhofer, Martina. The Everyday Life of the Emperor: Francis Joseph and His Imperial Court. Innsbruck-Wien: Haymon Taschenbuch, 2012. ISBN 9783852189277

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Emperor Franz Joseph I |

| German Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Franz Joseph I of Austria. |

- Biography at WorldWar1.com

- Details at Regiments.org at the Wayback Machine (archived December 19, 2007)

- Genealogy

- Mayerling tragedy

- Miklós Horthy reflects on Franz Josef

- Internet museum of Emperor Franz Joseph I, Wilhelm II and First World War

- Wien – Attentat – Kaiser Franz Joseph – Lasslo Libényi – Graf O'Donnell – Josef Ettenreich – Geschichte – Votivkirche at www.wien-vienna.at

| Franz Joseph I of Austria Born: 18 August 1830 Died: 21 November 1916 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ferdinand I & V |

Emperor of Austria King of Hungary 1848–1916 |

Succeeded by Charles I & IV |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Ferdinand I of Austria |

President of the German Confederation 1849–1866 |

Succeeded by William I of Prussia (President of the North German Confederation) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

.svg.png)