Frankish language

| Frankish / Old Franconian | |

|---|---|

| Native to | formerly the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Northern France, Western Germany |

| Era | 5th to the 9th century |

|

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

frk |

| Glottolog |

fran1264[1] |

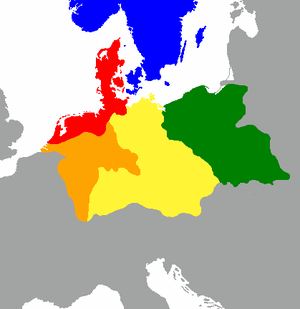

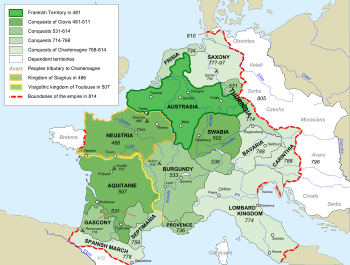

Frankish or Old Franconian (or, less correctly, Old Frankish) was the language spoken by the Germanic Franks in the Low Countries and adjacent parts of contemporary France and Germany between the 4th and 8th century. It belongs to the West Germanic language group and is thought to have given rise to the modern Franconian languages. The Franks descended from Germanic tribes that settled parts of the Netherlands and western Germany during the early Iron Age. From the 4th century, they are attested as extending into what is now the southern Netherlands and northern Belgium. In the 5th and 6th centuries, they expanded their realm and conquered Roman Gaul completely as well as client states such as Bavaria and Thuringia.

Knowledge of Frankish is almost entirely reconstructed from Old Dutch and from etyma and loanwords from Old French. A notable exception is the Bergakker inscription found in 1996, which may be a direct attestation of Old Franconian.

During this period, Frankish had a major influence on the lexicon, pronunciation and grammar of the Romance languages spoken in former Roman Gaul. As a result, many modern French words and placenames (including the country name "France") have a Germanic origin. Between the 5th and 9th centuries, the languages spoken by the Salian Franks in Belgium and the Netherlands evolved into Old Dutch (Old Low Franconian), while in Picardy and Île-de-France it was eventually eclipsed by Old French as the dominant language.

Difficulties arising from lack of attestation

Written texts of the language spoken by the Franks are extremely rare and much more limited when compared to Old English and Old High German. Most of the earliest texts written in the Low Countries were written in Latin. Some of these Latin texts however contained non-Latin words interspersed with the Latin text. These words are the only attestation of the language spoken by the Franks. Also, it is extremely hard to determine whether a text was actually written in the language spoken by the Franks, because the various Germanic dialects spoken at that time were much more closely related.

Nomenclature difficulties

The set of dialects spoken by the Franks before around 500 AD was probably not a separate language per se, but a set of Istvaeonic dialects in the West Germanic branch of Proto-Germanic. It is only around 500 AD that one can speak of a "Frankish" or "Franconian" language.

There is some confusion between "Frankish" and "Franconian", even though they essentially mean the same thing. The historical origins of this confusion are described in detail in a separate section below.

The English term "Old Frankish" is often rather unclearly used (including in this article) to refer to what should properly be called "Old Franconian". The term "Old Frankish" in English is vague, referring sometimes to language and sometimes to other cultural aspects. It is also problematic in that it is not the term used by philologists and it misrepresents a complicated linguistic situation.

In philology, the language spoken by the Salian Franks from around the 5th to the 10th century was a variety of "Old Franconian" called "Old Low Franconian" or, more commonly, "Old Dutch". (This use of two terms to refer to a single language is similar to way that "Anglo-Saxon" and "Old English" are both used to refer to the same language.) This language should properly be called "Old Low Franconian" or "Old Dutch". However, some people refer to this as "Old Frankish" because of its connection to the Frankish people and empire.

The English term "Old Frankish" is, for historical reasons, usually not used in the context of the Ripuarian Franks and their language. It is more often used in the Salian Frank and Dutch contexts. However, the Franks in Germany spoke a variety of Old Franconian. This could also (irregularly) be called Old Frankish.

To make things even more complicated, the language spoken by the Salian Franks is sometimes referred to as "Old West Low Franconian", not just "Old Low Franconian".

So the language spoken by the Salian Franks (including those who expanded into France) should be called "Old Dutch", but it is also referred to as "Old Franconian", "Old Low Franconian", "Old West Low Franconian" and (irregularly) "Old Frankish". The language is referred to by five different names.

It's also confusing that various German language dialects are sometimes called "Franconian", and are included as Franconian languages.

Origins in the Istvaeonic group of the West Germanic branch of Proto-Germanic (before 210 AD)

The Germanic languages are traditionally divided into three groups: West, East and North Germanic.[2] Their exact relation is difficult to determine, and they remained mutually intelligible throughout the Migration Period, so that some individual varieties are difficult to classify.

The language spoken by the Franks was part of the West Germanic language group, which had features from Proto-Germanic in the late Jastorf culture (ca. 1st century BC). The West Germanic group is characterized by a number of phonological and morphological innovations not found in North and East Germanic.[3] The West Germanic varieties of the time are generally split into three dialect groups: Ingvaeonic (North Sea Germanic), Istvaeonic (Weser-Rhine Germanic) and Irminonic (Elbe Germanic). While each had its own distinct characteristics, there certainly must have still been a high degree of mutual intelligibility between these dialects. In fact, it is unclear whether the West Germanic continuum of this time period, or indeed Franconian itself, should still be considered a single language or that it should be considered a collection of similar dialects.[4]

In any case, it appears that the Frankish tribes, or the later Franks, fit primarily into the Istvaeonic dialect group, with certain Ingvaeonic influences towards the northwest (still seen in modern Dutch), and more Irminonic (High German) influences towards the southeast.

Language of the early Salian and Ripuarian Franks (210–500 AD)

Modern scholars of the Migration Period are in agreement that the Frankish identity emerged at the first half of the 3rd century out of various earlier, smaller Germanic groups, including the Salii, Sicambri, Chamavi, Bructeri, Chatti, Chattuarii, Ampsivarii, Tencteri, Ubii, Batavi and the Tungri. It is speculated that these tribes originally spoke a range of related Istvaeonic dialects in the West Germanic branch of Proto-Germanic. Sometime in the 4th or 5th centuries, it becomes appropriate to speak of Old Franconian rather than an Istvaeonic dialect of Proto-Germanic.

Very little is known about what the language was like during this period. One older runic sentence (dating from around 425–450 AD) is on the sword sheath of Bergakker. Another early sentence from the early 6th century AD is found in the Lex Salica. This phrase was used to free a serf:

- "Maltho thi afrio lito"

- (I say, I free you, half-free.)

These are the earliest sentences yet found of Old Franconian.

During this early period, the Franks were divided politically and geographically into two groups: the Salian Franks and the Ripuarian Franks. The language (or set of dialects) spoken by the Salian Franks during this period is sometimes referred to as early "Old Low Franconian", and consisted of two groups: "Old West Low Franconian" and "Old East Low Franconian". The language (or set of dialects) spoken by the Ripuarian Franks are referred to just as Old Franconian dialects (or, by some, as Old Frankish dialects).

However, as already stated above, it may be more accurate to think of these dialects not as early Old Franconian but as Istvaeonic dialects in the West Germanic branch of Proto-Germanic.

Language of the Franks during the Frankish Empire (500–900 AD)

At around 500 AD the Franks probably still spoke a range of related dialects and languages rather than a single uniform dialect or language.[5] The language of both government and the Church was Latin.

Core Frankish territory in the Low Countries and in the Cologne area

During the expansion into France and Germany, many Frankish people remained in the original core Frankish territories in the north (i.e. southern Netherlands, Flanders, a small part of northern France and the adjoining area in Germany centred on Cologne). The Franks united as a single group under Salian Frank leadership around 500 AD. Politically, the Ripuarian Franks existed as a separate group only until about 500 AD. After that they were subsumed under the Salic Franks. The Franks were united, but the various Frankish groupings must have continued to live in the same areas, and speak the same dialects, although as a part of the growing Frankish Empire.

There must have been a close relationship between the various Franconian dialects. There was also a close relationship between Old Low Franconian (i.e. Old Dutch) and its neighbouring Saxon-based languages and dialects to the north and northeast, i.e. Old Saxon and the related Anglo-Saxon dialects called Old English and Old Frisian.

A widening cultural divide grew between the Franks remaining in the north and the rulers far to the south.[6] Franks continued to reside in their original territories and to speak their original dialects and languages. It is not known what they called their language, but it is possible that they always called it "Diets" (i.e. "the people's language"), or something similar.

Philologists think of Old Dutch and Old West Low Franconian as being the same language. However, sometimes reference is made to a transition from the language spoken by the Salian Franks to Old Dutch. The language spoken by the Salian Franks must have developed significantly during the seven centuries from 200 to 900 AD. At some point the language spoken by the Franks must have become identifiably Dutch. Because Franconian texts are almost non-existent and Old Dutch texts scarce and fragmentary, it is difficult to determine when such a transition occurred, but it is thought to have happened by the end of the 9th century and perhaps earlier. By 900 AD the language spoken was recognisably an early form of Dutch, but that might also have been the case earlier.[7] Old Dutch made the transition to Middle Dutch around 1150. A Dutch-French language boundary came into existence (but this was originally south of where it is today).[6][7] Even though living in the original territory of the Franks, these Franks seem to have broken with the endonym "Frank" around the 9th century. By this time the Frankish identity had changed from an ethnic identity to a national identity, becoming localized and confined to the modern Franconia in Germany and principally to the French province of Île-de-France.[8]

France

The Franks expanded south into Gaul. Although the Franks would eventually conquer all of Gaul, speakers of Old Franconian apparently expanded in sufficient numbers only into northern Gaul to have a linguistic effect. For several centuries, northern Gaul was a bilingual territory (Vulgar Latin and Franconian). The language used in writing, in government and by the Church was Latin. Eventually, the Franks who had settled more to the south of this area in northern Gaul started adopting the Vulgar Latin of the local population. This Vulgar Latin language acquired the name of the people who came to speak it (Frankish or Français); north of the French-Dutch language boundary, the language was no longer referred to as "Frankish" (if it ever was referred to as such) but rather came to be referred to as "Diets", i.e. the "people's language".[7] Urban T. Holmes has proposed that a Germanic language continued to be spoken as a second tongue by public officials in western Austrasia and Neustria as late as the 850s, and that it completely disappeared as a spoken language from these regions only during the 10th century.[9]

Germany

The Franks also expanded their rule southeast into parts of Germany. Their language had some influence on local dialects, especially for terms relating to warfare. However, since the language of both the administration and the Church was Latin, this unification did not lead to the development of a supra-regional variety of Franconian nor a standardized German language. At the same time that the Franks were expanding southeast into Germany, there were linguistic changes in Germany. The High German consonant shift (or second Germanic consonant shift) was a phonological development (sound change) that took place in the southern parts of the West Germanic dialect continuum in several phases, probably beginning between the 3rd and 5th centuries AD, and was almost complete before the earliest written records in the High German language were made in the 9th century. The resulting language, Old High German, can be neatly contrasted with Low Franconian, which for the most part did not experience the shift.

Modern descendants of Old Franconian

The set of dialects of the Franks who continued to live in their original territory in the Low Countries eventually developed in three different ways.

- The dialects spoken by the Salian Franks in the Low Countries (Old Dutch, also referred to as Old West Low Franconian) developed into the Dutch language, which itself has a number of dialects. Afrikaans branched off Dutch.

- The Old East Low Franconian dialects are represented today in Limburgish, which is sometimes referred to (especially by Germans) as Low Rhenish or Meuse-Rhenish. Limburgish itself has a number of dialects. It is sometimes considered to be a separate language and sometimes a dialect of Dutch or German.

- It is speculated that the dialects originally spoken by the Ripuarian Franks in Germany possibly developed into, or were subsumed under, the German dialects called the Central Franconian dialects (Ripuarian Franconian, Moselle Franconian and Rhenish Franconian). These languages and dialects were later affected by serious language changes (such as the High German consonant shift), which resulted in the emergence of dialects that are now considered German dialects. Today, the Central Franconian dialects are spoken in the core territory of the Ripuarian Franks. Although there may not be definite proof to say that the dialects of the Ripuarian Franks (about which very little is known) developed into the Central Franconian dialects, there are—apart from mere probability—some pieces of evidence, most importantly the development -hs → ss and the loss of n before spirans, which is found throughout Central Franconian but nowhere else in High German. Compare Luxembourgish Uess ("ox"), Dutch os, German Ochse; and (dated) Luxembourgish Gaus ("goose"), Old Dutch gās, German Gans. The language spoken by Charlemagne was probably the dialect that later developed into the Ripuarian Franconian dialect.[10]

Because of the geographical correspondence, it is particularly tempting to think that the languages and dialects spoken by the early Franks are represented today by the languages and dialects of the Rhenish fan.

The Frankish Empire later extended throughout neighbouring France and Germany. The language of the Franks had some influence on the local languages (especially in France), but never took hold as a standard language because Latin was the international language at the time. Ironically, the language of the Franks did not develop into the lingua franca.

Historical views of the linguistic concept and the meaning of "Franconian" and "Frankish"

"Franconian" is entirely an English word. Continental Europeans use the equivalent of "Frankish", from the original Latin Franci, with the same meaning; for example, the German for Old Franconian is alt-Fränkisch. The Dutch linguist, Jan van Vliet (1622–1666), uses Francica or Francks to mean the language of the oude Francken ("Old Franks"). For van Vliet, Francks descended from oud Teuts, what is today referred to in English as the Proto-Germanic language.[11]

Old Franconian

The name "Franconian", an English adjective made into a noun, comes from the official Latin name of an area (and later Duchy) in the Middle Ages known as Franconia (German Franken). If being in the territory of the original Franci is a criterion of being Frankish, it was not originally Frankish, but Alemannic, as the large Roman base at Mainz, near the confluence of the Main and the Rhine, kept the Franci and the Suebi, core tribe of the Alemanni, apart. When the Romans withdrew, the fort became a major base of the Ripuarian Franks, who promptly moved up the Main, founded Frankfurt ("the ford of the Franks"), established a government over the Suebi between the Rhine and the Danube, and proceeded to assimilate them to all things Frankish, including the dialects. The Ripuarian Franks at that time were not acting as such, but were simply part of the Frankish empire under the Carolingian dynasty.

Franconian is the only English single word describing the region called Franken by the Germans. The population considered as native is also called Franken, who speak a language called Fränkisch, which is dialects included in German. In the Middle Ages, before German prevailed officially over Latin, the Latinizations, Franconia and Francones, were used in official documents. Since Latin was the scholarly lingua franca, the Latin forms spread to Britain as well as to other nations. English speakers had no reason to convert to Franken; moreover, "Frankish" was already being used for French and Dutch. Franconian was kept.

The English did not have much to say about Franconian until the 18th century, except that it was "High Dutch”, and "German”. In 1767 Thomas Salmon published:[12]

| “ | The language of the Germans is High Dutch, of which there are many dialects, so different, that the people of one province scarce understand those of another. | ” |

"Province", as it was applied to Germany, meant one of the ten Reichskreise of the Holy Roman Empire. Slingsby Bethel had published a description of them in a political treatise of 1681,[13] referring to each of them as a "province," and describing, among them, "The Franconian Circle." Slingsby's language development goes no further than "High Germany," where "High Dutch" was spoken and "the lower parts of Germany," speaking, presumably, Low Dutch. Salmon's implicit identification of dialects with Reichskreise speech is the very misconception found objectionable by Green and Siegmund:[5]

| “ | Here we are also touching upon the problem of languages, for many scholars … proceed from the assumption that they were ethnic languages/dialects (Stammessprachen) … the very opposite goes for the Franks … | ” |

In the mid-19th century, a time when the Germans were attempting to define a standard German, the term. alt-Fränkisch made its appearance, which was an adjective meaning "old-fashioned." It came into English immediately as "Old Franconian." English writings mentioned Old Franconian towns, songs and people, among other things. To the linguists, the term was a windfall, as it enabled them to distinguish a Stammsprach. For example, in 1863 Gustave Solling's Diutiska identified the Pledge of Charles the Bald, which is in Old High German, as Old Franconian.[14] He further explains that the latter is an Upper German dialect.

By the end of the century the linguists understood that between "Low Dutch" and "High Dutch" was a partially altered continuum, which they called Middle, or Central, German. It had been grouped with Upper, or High, German. This "Middle" was between low and high, as opposed to the Chronological Middle High German, between old and new. In 1890 Ernest Adams defined Old Franconian as an Old High German dialect spoken on the middle and upper Rhine;[15] i.e., it went beyond the limits of Franconia to comprise also the dialect continuum of the Rhineland. His earlier editions, such as the 1858, did not feature any Old Franconian.

Old Low Franconian

After the English concept of Franconian had expanded to encompass the Rhineland in the 1850s and 1860s, a paradox seemed to prevent it from spreading to the lower Rhine. Language there could not be defined as High German in any way. In 1862 Max Müller pointed out that Jacob Grimm had applied the concept of "German" grammar to ten languages, which "all appear to have once been one and the same."[16] One of these was the "Netherland Language, which appears to have been produced by the combined action of the older Franconian and Saxon, and stands therefore in close relation to the Low German and the Friesian. Its descendants now are the Flemish in Belgium and Dutch in Holland." Müller, after describing Grimm's innovation of the old, middle and new phases of High German, contradicts himself by reiterating that Franconian was a dialect of the upper Rhine.

After somewhat over a generation a formal solution had been universally accepted: Franconian had a low phase. An 1886 work by Strong and Meyer defined Low Franconian as the language "spoken on the lower Rhine."[17] Their presentation included an Upper, Middle and Lower Franconian, essentially the modern scheme. Low Franconian, however, introduced another conflict of concepts, as Low Franconian must mean, at least in part, Dutch. Here Strong and Meyer are anachronistic on behalf of consistency, an error that would not have been made by native Dutch or German speakers. According to them, "Franconian ceases to be applied to this language; it is then called Netherlandish (Dutch)…." Only the English ever applied Franconian anywhere; moreover, Netherlandish had been in use since the 17th century, after which Dutch was an entirely English word. The error had been corrected by the time of Wright's Old High German Primer two years later, in 1888. Wright identifies Old Low Franconian with Old Dutch,[18] both terms used only in English.

Old Frankish

Before it acquired the present name "Germanic", "Germanic" was known as "Teutonic". The Germanics were literary witnesses in history to the alteration of their early Germanic speech into multiple languages. The early speech then became Old Teutonic. However, this Old Teutonic remained out of view, prior to the earliest writings, except for the language of the runic inscriptions, which, being one or two words and numbering less than a thousand, are an insufficient sample to verify any but a few phonetic details of the reconstructed proto-language.

Van Vliet and his 17th century contemporaries inherited the name and the concept "Teutonic". Teutones and Teutoni are names from classical Latin referring to the entire population of Germanics in the Proto-Germanic era, although there were tribes specifically called Teutons. Between "Old Dutch" (meaning the earliest Dutch language) and "Old Teutonic", Van Vliet inserted "Frankish", the language of the Old Franks. He was unintentionally ambiguous about who these "Old Franks" were linguistically. At one point in his writing they were referred to as "Old High German" speakers, at another, "Old Dutch" speakers, and at another "Old French" speakers. Moreover, he hypothesized at one point that Frankish was a reflection of Gothic. The language of the literary fragments available to him was not clearly identified. Van Vliet was searching for a group he thought of as the "Old Franks", which to him included everyone from Mainz to the mouth of the Rhine.

By the end of the 17th century the concept of Old Frankish, the ancestor language of Dutch, German, and the Frankish words in Old French had been firmly established. After the death of Junius, a contemporary of Van Vliet, Johann Georg Graevius said of him in 1694 that he collected fragments of vetere Francica, "Old Frankish," ad illustrandam linguam patriam, "for the elucidation of the mother tongue."[19] The concept of the Dutch vetere Francica, a language spoken by the Franks mentioned in Gregory of Tours and of the Carolingian Dynasty, which at one end of its spectrum became Old Dutch, and at the other, Old High German, threw a shadow into neighboring England, even though the word "Franconian", covering the same material, was already firmly in use there. The shadow remains.

The term "Old Frankish" in English is vague and analogous, referring either to language or to other aspects of culture. In the most general sense, "old" means "not the present", and "Frankish" means anything claimed to be related to the Franks from any time period. The term "Old Frankish" has been used of manners, architecture, style, custom, government, writing and other aspects of culture, with little consistency. In a recent history of the Germanic people, Ozment used it to mean the Carolingian and all preceding governments and states calling themselves Franks through the death of the last admittedly Frankish king, Conrad I of Germany, in 919, and his replacement by a Saxon.[20] This "Old Frankish" period, then, beginning in the Proto-Germanic period and lasting until the 10th century, is meant to include Old High German, Old Dutch and the language that split to form Low German and High German.

Proto-Frankish

Germanic is so diverse as to defy attempts to arrive at a uniform Germanic ancestor. Max Müller finally wrote in the lectures on the Science of Language, under the heading, "No Proto-Teutonic Language:"[21]

| “ | We must not suppose that before that time [7th century] there was one common Teutonic language spoken by all German tribes and that it afterwards diverged into two streams — the High and the Low. There never was a common, uniform Teutonic language; … This is a mere creation of grammarians who cannot understand a multiplicity of dialects without a common type. | ” |

Historical linguistics did not validate his rejection of the Tree model, but it did apply the Wave model to explain the diversity. Features can cross language borders in a wave to impart characteristics not explicable by descent from the language's ancestor. The linguists of the early 19th century, including Müller, had already foreshadowed the Wave Model with a concept of the "blend" of languages, of which they made such frequent use in the case of Germanic that it was difficult to discern any unblended language. These hypothetical "pure" languages were about as inaccessible as the Proto-Germanic Old Frankish; that is, pure guesswork. Dialects or languages in the sense of dialects became the major feature of the Germanic linguistic landscape.

Old Dutch

A second term in use by Van Vliet was oud Duijts, "Old Dutch", where Duijts meant "the entire Continental Germanic continuum". The terms Nederlandsch and Nederduijts were coming into use for contemporary Dutch. Van Vliet used the oud Duijts ambiguously to mean sometimes Francks, sometimes Old Dutch, and sometimes Middle Dutch, perhaps because the terms were not yet firm in his mind.[22] Duijts had been in general use until about 1580 to refer to the Dutch language, but subsequently was replaced by Nederduytsch.

English linguists lost no time in bringing Van Vliet's oud Duijts into English as "Old Dutch". The linguistic noun "Old Dutch", however, competed with the adjective "Old Dutch", meaning an earlier writing in the same Dutch, such as an old Dutch rhyme, or an old Dutch proverb. For example, Brandt's "old Dutch proverb", in the English of his translator, John Childe, mentioned in 1721:[23] Eendracht maekt macht, en twist verquist, "Unity gives strength, and Discord weakness," means contemporary Dutch and not Old Dutch. On the frontispiece, Childe refers to the language in which the book was written as "the original Low Dutch". Linguistic "Old Dutch" had already become "Low Dutch", the contemporary language, and "High Dutch", or High German. On the other hand, "Old Dutch" was a popular English adjective used in the 18th century with reference to people, places and things.

Influence on French

Most French words of Germanic origin came from Frankish (some others are English loanwords[24]), often replacing the Latin word which would have been used. It is estimated that modern French took approximately 1000 stem words from Old Franconian.[25] Many of these words were concerned with agriculture (e.g. French: jardin "garden"), war (e.g. French: guerre "war") or social organization (e.g. French: baron "baron"). Old Franconian has introduced the modern French word for the nation, France (Francia), meaning "land of the Franks", as well as possibly the name for the Paris region, Île-de-France from Lidle Franken or "Little Franconia".

The influence of Franconian on French is decisive for the birth of the early langue d'oïl compared to the other Romance languages, that appeared later such as langue d'oc, Romanian, Portuguese and Catalan, Italian, etc., because its influence was greater than the respective influence of Visigothic and Lombardic (both Germanic languages) on the langue d'oc, the Romance languages of Iberia, and Italian. Not all of these loanwords have been retained in modern French. French has also passed on words of Franconian origin to other Romance languages, and to English.

Old Franconian has also left many etyma in the different Northern Langues d'oïls such as Picard, Champenois, Bas-Lorrain and Walloon, more than in Common French, and not always the same ones.[26]

See below a non-exhaustive list of French words of Frankish origin. An asterisk prefixing a term indicates a reconstructed form of the Frankish word. Most Franconian words with the phoneme w, changed it to gu when entering Old French and other Romance languages; however, the northern langue d'oïl dialects such as Picard, Northern Norman, Walloon, Burgundian, Champenois and Bas-Lorrain retained the [w] or turned it into [v]. Perhaps the best known example is the Franconian *werra ("war" < Old Northern French werre, compare Old High German werre "quarrel"), which entered modern French as guerre and guerra in Italian, Occitan, Catalan, Spanish and Portuguese. Other examples include "gant" ("gauntlet", from *want) and "garder" ("to guard", from *wardōn). Franconian words starting with the phoneme s changed to es when entering Old French (e.g. Franconian skirm and Old French escremie > Old Italian scrimia > Modern French escrime).[27]

| Current French word | Old Franconian | Dutch or other Germanic cognates | Latin/Romance |

|---|---|---|---|

| affranchir "to free" | *frank "freeborn; unsubjugated, answering to no one", nasalized variant of *frāki "rash, untamed, impudent" | Du frank "unforced, sincere, frank", vrank "carefree, brazen", Du frank en vrij (idiom) "free as air"[28] Du Frankrijk "France", Du vrek "miser", OHG franko "free man" Norwegian: frekk "rude" | L līberāre |

| alène "awl" (Sp alesna, It lesina) | *alisna | MDu elsene, else, Du els | L sūbula |

| alise "whitebeam berry" (OFr alis, alie "whitebeam") | *alísō "alder"[29] | MDu elze, Du els "alder" (vs. G Erle "alder"); Du elsbes "whitebeam", G Else "id." | non-native to the Mediterranean |

| baron | *baro "freeman", "bare of duties" | MDu baren "to give birth", Du bar "gravely", "bare", OHG baro "freeman", OE beorn "noble" | Germanic cultural import |

| bâtard "bastard" (FrProv bâsco) | *bāst "marriage"[30] | MDu bast "lust, heat, reproductive season", WFris boaste, boask "marriage" | L nothus |

| bâtir "to build" (OFr bastir "to baste, tie together") bâtiment "building" bastille "fortress" bastion "fortress" |

*bastian "to bind with bast string" | MDu besten "to sew up, to connect", OHG bestan "to mend, patch", NHG basteln "to tinker"; MDu best "liaison" (Du gemenebest "commonwealth") | L construere (It costruire) |

| bière "beer" | *bera | Du bier | L cervisia |

| blanc, blanche "white" | *blank | Du blinken "to shine", blank "white, shining" | L albus |

| bleu "blue" (OFr blou, bleve) | *blao | MDu blā, blau, blaeuw, Du blauw | L caeruleus "light blue", lividus "dark blue" |

| bois "wood, forest" | *busk "bush, underbrush" | MDu bosch, busch, Du bos "forest", "bush" | L silva "forest" (OFr selve), L lignum "wood" (OFr lein)[31] |

| bourg "town/city" | *burg or *burc "fortified settlement" | ODu burg, MDu burcht Got. baurg OHG burg OE burh, OLG burg, ON borg | L urbs "fortified city", Late Latin burgus |

| broder "to embroider" (OFr brosder, broisder) | *brosdōn, blend of *borst "bristle" and *brordōn "to embroider" | G Borste "boar bristle", Du borstel "bristle"; OS brordōn "to embroider, decorate", brord "needle" | L pingere "to paint; embroider" (Fr peindre "to paint") |

| broyer "to grind, crush" (OFr brier) | *brekan "to break" | Du breken "to break", | LL tritāre (Occ trissar "to grind", but Fr trier "to sort"), LL pistāre (It pestare "to pound, crush", OFr pester), L machīnare (Dalm maknur "to grind", Rom măcina, It macinare) |

| brun "brown" | ? | MDu brun and Du bruin "brown" [32] | |

| choquer "to shock" | *skukjan | Du schokken "to shock, to shake" | |

| choisir "to choose" | *kiosan | MDu kiesen, Du kiezen, keuze | L eligēre (Fr élire "to elect"), VL exeligēre (cf. It scegliere), excolligere (Cat escollir, Sp escoger, Pg escolher) |

| chouette "barn owl" (OFr çuete, dim. of choë, choue "jackdaw") | *kōwa, kāwa "chough, jackdaw" | MDu couwe "rook", Du kauw, kaauw "chough" | not distinguished in Latin: L būbō "owl", ōtus "eared owl", ulula "screech owl", ulucus likewise "screech owl" (cf. Sp loco "crazy"), noctua "night owl" |

| cresson "watercress" | *kresso | MDu kersse, korsse, Du kers, dial. kors | L nasturtium, LL berula (but Fr berle "water parsnip") |

| danser "to dance" (OFr dancier) | *dansōn[33] | OHG dansōn "to drag along, trail"; further to MDu densen, deinsen "to shrink back", Du deinzen "to stir; move away, back up", OHG dinsan "to pull, stretch" | LL ballare (OFr baller, It ballare, Pg bailar) |

| déchirer "to rip, tear" (OFr escirer) | *skerian "to cut, shear" | MDu scēren, Du scheren "to shave, shear", scheuren "to tear" | VL extracticāre (Prov estraçar, It stracciare), VL exquartiare "to rip into fours" (It squarciare, but Fr écarter "to move apart, distance"), exquintiare "to rip into five" (Cat/Occ esquinçar) |

| dérober "to steal, reave" (OFr rober, Sp robar) | *rōbon "to steal" | MDu rōven, Du roven "to rob" | VL furicare "to steal" (It frugare) |

| écang "swingle-dag" | *swank "bat, rod" | MDu swanc "wand, rod", Du (dial. Holland) zwang "rod" | L pistillum (Fr dial. pesselle "swingle-dag") |

| écran "screen" (OFr escran) | *skrank[34] | MDu schrank "chassis"; G Schrank "cupboard", Schranke "fence" | L obex |

| écrevisse "crayfish" (OFr crevice) | *krebit | Du kreeft "crayfish, lobster" | L cammārus "crayfish" (cf. Occ chambre, It gambero, Pg camarão) |

| éperon "spur" (OFr esporon) | *sporo | MDu spōre, Du spoor | L calcar |

| espier "to spy" espion "male spy", espionne "female spy", espionnage "espionnage" |

*spehōn "to spy" | Du spieden, bespieden "to spy", HG spähen "to peer, to peek, to scout", | |

| escrime "fencing" < Old Italian scrimia < OFr escremie from escremir "fight" | *skirm "to protect" | Du schermen "to fence", scherm "(protective) screen", bescherming "protection", afscherming"shielding" | |

| étrier "stirrup" (OFr estrieu, estrief) | *stīgarēp, from stīgan "to go up, to mount" and rēp "band" | MDu steegereep, Du stijgreep, stijgen "to rise", steigeren | LL stapia (later ML stapēs), ML saltatorium (cf. MFr saultoir) |

| flèche "arrow" | *fliukka | Du vliek "arrow feather", MDu vliecke, OS fliuca (MLG fliecke "long arrow") | L sagitta (OFr saete, Pg seta) |

| frais "fresh" (OFr freis, fresche) | *friska "fresh" | Du vers "fresh", fris "cold" | |

| franc "free, exempt; straightforward, without hassle" (LL francus "freeborn, freedman") France "France" (OFr Francia) franchement "frankly" |

*frank "freeborn; unsubjugated, answering to no one", nasalized variant of *frāki "rash, untamed, impudent" | MDu vrec "insolent", Du frank "unforced, sincere, frank", vrank "carefree, brazen",[35] Du Frankrijk "France", Du vrek "miser", OHG franko "free man" | L ingenuus "freeborn" L Gallia[36] |

| frapper "to hit, strike" (OFr fraper) | *hrapan "to jerk, snatch"[37] | Du rapen "gather up, collect", G raffen "to grab" | L ferire (OFr ferir) |

| frelon "hornet" (OFr furlone, ML fursleone) | *hurslo | MDu horsel, Du horzel | L crābrō (cf. It calabrone) |

| freux "rook" (OFr frox, fru) | *hrōk | MDu roec, Du roek | not distinguished in Latin |

| galloper "to gallop" | *wala hlaupan "to run well" | Du wel "good, well" + lopen "to run" | |

| garder "to guard" | *wardōn | MDu waerden "to defend", OS wardōn | L cavere, servare |

| gant "gauntlet" | *want | Du want "gauntlet" | |

| givre "frost (substance)" | *gibara "drool, slobber" | EFris gever, LG Geiber, G Geifer "drool, slobber" | L gelū (cf. Fr gel "frost (event); freezing") |

| glisser "to slip" (OFr glier) | *glīdan "to glide" | MDu glīden, Du glijden "to glide"; Du glis "skid"; G gleiten, Gleis "track" | ML planare |

| grappe "bunch (of grapes)" (OFr crape, grape "hook, grape stalk") | *krāppa "hook" | MDu crappe "hook", Du (dial. Holland) krap "krank", G Krapfe "hook", (dial. Franconian) Krape "torture clamp, vice" | L racemus (Prov rasim "bunch", Cat raïm, Sp racimo, but Fr raisin "grape") |

| gris "grey" | *grîs "grey" | Du grijs "grey" | cinereus "ash-coloured, grey" |

| guenchir "to turn aside, avoid" | *wenkjan | Du wankelen "to go unsteady" | |

| guérir "to heal, cure" (OFr garir "to defend") guérison "healing" (OFr garison "healing") |

*warjan "to protect, defend" | MDu weeren, Du weren "to protect, defend", Du bewaren "to keep, preserve" | L sānāre (Sard sanare, Sp/Pg sanar, OFr saner), medicāre (Dalm medcuar "to heal") |

| guerre "war" | *werra "war" | Du war[38] or wirwar "tangle",[39] verwarren "to confuse" | L bellum |

| guigne "heart cherry" (OFr guisne) | *wīksina[40] | G Weichsel "sour cherry", (dial. Rhine Franconian) Waingsl, (dial. East Franconian) Wassen, Wachsen | non-native to the Mediterranean |

| haïr "to hate" (OFr haïr "to hate") haine "hatred" (OFr haïne "hatred") |

*hatjan | Du haten "to hate", haat "hatred" | L odium |

| hanneton "cockchafer" | *hāno "rooster" + -eto (diminutive suffix) with sense of "beetle, weevil" | Du haan "rooster", leliehaantje "lily beetle", bladhaantje "leaf beetle", G Hahn "rooster", (dial. Rhine Franconian) Hahn "sloe bug, shield bug", Lilienhähnchen "lily beetle" | LL bruchus "chafer" (cf. Fr dial. brgue, beùrgne, brégue), cossus (cf. SwRom coss, OFr cosson "weevil") |

| haubert "hauberk" | *halsberg "neck-cover"[41] | Du hals "neck" + berg "cover" (cf Du herberg "hostel") | |

| héron "heron" | *heigero, variant of *hraigro | MDu heiger "heron", Du reiger "heron" | L ardea |

| houx "holly" | *hulis | MDu huls, Du hulst | L aquifolium (Sp acebo), later VL acrifolium (Occ grefuèlh, agreu, Cat grèvol, It agrifoglio) |

| jardin "garden" (VL hortus gardinus "enclosed garden", Ofr jardin, jart)[42][43] | *gardo "garden" | Du gaard "garden", boomgaard "orchard"; OS gardo "garden" | L hortus |

| lécher "to lick" (OFr lechier "to live in debauchery") | *leccōn "to lick" | MDu lecken, Du likken "to lick" | L lingere (Sard línghere), lambere (Sp lamer, Pg lamber) |

| maçon "bricklayer" (OFr masson, machun) | *mattio "mason"[44] | Du metsen "to mason", metselaar "masoner"; OHG mezzo "stonemason", meizan "to beat, cut", G Metz, Steinmetz "mason" | VL murator (Occ murador, Sard muradore, It muratóre) |

| maint "many" (OFr maint, meint "many") | *menigþa "many" | Du menig "many", menigte "group of people" | |

| marais "marsh, swamp" | *marisk "marsh" | MDu marasch, meresch, maersc, Du meers "wet grassland", (dial. Holland) mars | L paludem (Occ palun, It palude) |

| maréchal "marshal" maréchausse "military police" |

*marh-skalk "horse-servant" | ODu marscalk "horse-servant" (marchi "mare" + skalk "servant"); MDu marscalc "horse-servant, royal servant" (mare "mare" + skalk "serf"); Du maarschalk "marshal" (merrie "mare" + schalk "comic", schalks "teasingly") | |

| nord "north" | *Nortgouue (790–793 A.D.) "north" + "frankish district" (Du gouw, Deu Gau, Fri/LSax Go) | Du noord or noorden "north"[45] | L septemtriones "north, north wind, northern regions, seven stars near the north pole", boreas "north wind, north", aquilo"stormy wind, north wind, north", septentriones north wind, north, northern regions, seven stars near the north pole", septentrio "north, great, north regions", septemtrio "north, great, north regions", aquilonium "northerly regions, north", borras "north" septemtrional "north", septentrional "north" |

| osier "osier (basket willow); withy" (OFr osière, ML auseria) | *halster[46] | MDu halster, LG dial. Halster, Hilster "bay willow" | L vīmen "withy" (It vimine "withy", Sp mimbre, vimbre "osier", Pg vimeiro, Cat vímet "withy"), vinculum (It vinco "osier", dial. vinchio, Friul venc) |

| patte "paw" | *pata "foot sole" | Du poot "paw",[47] Du pets "strike"; LG Pad "sole of the foot";[48] further to G Patsche "instrument for striking the hand", Patschfuss "web foot", patschen "to dabble", (dial. Bavarian) patzen "to blot, pat, stain"[49] | Vulg LPauta,[47] LL branca "paw" (Sard brànca, It brince, Rom brîncă, Prov branca, Romansh franka, but Fr branche "treelimb"), see also Deu Pranke |

| poche "pocket" | *poka "pouch" | MDu poke, G dial. Pfoch "pouch, change purse" | L bulga "leather bag" (Fr bouge "bulge"), LL bursa "coin purse" (Fr bourse "money pouch, purse", It bórsa, Sp/Pg bolsa) |

| riche "rich" | *riki "rich" | MDu rike, Du rijk "kingdom", "rich" | L ŏpĭpărus |

| sale "dirty" | *salo "pale, sallow" | MDu salu, saluwe "discolored, dirty", Du (old) zaluw "tawny" | L succidus (cf. It sucido, Sp sucio, Pg sujo, Ladin scich, Friul soç) |

| salle "room" | *sala "hall, room" | ODu zele "house made with sawn beams", Many place names: "Melsele", "Broeksele" (Brussels) etc. | |

| saule "willow" | *salha "sallow, pussy willow" | OHG salaha, G Salweide "pussy willow", OE sealh | L salix "willow" (OFr sauz, sausse) |

| saisir "to seize, snatch; bring suit, vest a court" (ML sacīre "to lay claim to, appropriate") | *sakan "to take legal action"[50] | Du zeiken "to nag, to quarrel", zaak "court case", OS sakan "to accuse", OHG sahhan "to strive, quarrel, rebuke", OE sacan "to quarrel, claim by law, accuse"; | VL aderigere (OFr aerdre "to seize") |

| standard "standard" (OFr estandart "standard") | *standhard "stand hard, stand firm" | Du staan (to stand) + hard "hard" | |

| tamis "sieve" (It tamigio) | *tamisa | MDu temse, teemse, obs. Du teems "sifter" | L crībrum (Fr crible "riddle, sift") |

| tomber "to fall" (OFr tumer "to somersault") | *tūmōn "to tumble" | Du tuimelen "to tumble", OS/OHG tūmōn "to tumble", | L cædere (obsolete Fr cheoir) |

| trêve "truce" | *treuwa "loyalty, agreement" | Du trouw "faithfulness, loyalty" | L pausa (Fr pause) |

| troène "privet" (dialectal truèle, ML trūlla) | *trugil "hard wood; small trough" | OHG trugilboum, harttrugil "dogwood; privet", G Hartriegel "dogwood", dialectally "privet", (dial. Eastern) Trögel, archaic (dial. Swabian) Trügel "small trough, trunk, basin" | L ligustrum |

| tuyau "pipe, hose" (OFr tuiel, tuel) | *þūta | MDu tūte "nipple; pipe", Du tuit "spout, nozzle", OE þwēot "channel; canal" | L canna "reed; pipe" (It/SwRom/FrProv cana "pipe") |

Influence on German

Franconian is the historic basis of the Central Franconian and Low Franconian dialects spoken today in western Germany (largely the states of Rhineland-Palatinate and Saarland, as well as the south-western half of North Rhine-Westphalia). These dialects have, however, had little impact in the emergence of modern Standard German.

The Franks conquered adjoining territories of Germany (including the territory of the Allemanni). The Frankish legacy survives in these areas, for example, in the names of the city of Frankfurt and the area of Franconia. The Franks brought their language with them from their original territory and, as in France, it must have had an effect on the local dialects and languages. However, it is relatively difficult for linguists today to determine what features of these dialects are due to Frankish influence, because the latter was in large parts obscured, or even overwhelmed, by later developments.

Influence on Latin

Franconian also had an influence on late Latin itself. Latin words with Franconian roots include sacire, meaning "seize" (from Franconian sekjan, related to English "seek").

Old French

Franconian speech habits are also responsible for the replacement of Latin cum ("with") with aboc (a Franconian corruption of apud hoc "near this" ≠ Italian, Spanish con) in Old French (Modern French avec), and for the use of a non tonal form of Latin homo "man" : on one side homme "man" and on the other side Old French hum, hom, om > modern on, indefinite pronoun meaning "we", "it", etc. (compare German der Mann "man" and man, indefinite pronoun).

Influence on English

English also has many words with Franconian roots, usually through Old French e.g. random (via Old French randon, Old French verb randir, from *rant "a running"), standard (via Old French estandart, from *standhard "stand firm"), scabbard (via Anglo-French *escauberc, from *skar-berg), grape, stale, march (via Old French marche, from *marka) among others.

Influence on other languages

A few Italian words are of Franconian origin, too. They entered the vulgar language after the Frankish Empire annexed the Lombardic Kingdom of Italy.

See also

- Low Franconian languages

- Franconian languages

- List of French words of Germanic origin

- List of Portuguese words of Franconian origin

- List of Spanish words of Franconian origin

- Old High German

- History of French

Notes and references

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Frankish". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ Hawkins, John A. (1987). "Germanic languages". In Bernard Comrie. The World's Major Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 68–76. ISBN 0-19-520521-9.

- ↑ Robinson, Orrin W. (1992). Old English and Its Closest Relatives. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2221-8.

- ↑ Graeme Davis (2006:154) notes "the languages of the Germanic group in the Old period are much closer than has previously been noted. Indeed it would not be inappropriate to regard them as dialects of one language." In: Davis, Graeme (2006). Comparative Syntax of Old English and Old Icelandic: Linguistic, Literary and Historical Implications. Bern: Peter Lang. ISBN 3-03910-270-2.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Green, D.H.; Frank Siegmund; Center for Interdisciplinary Research on Social Stress (2003). The continental Saxons from the migration period to the tenth century: an ethnographic perspective. Studies in historical archaeoethnology, v.6. Suffolk: Woodbridge. p. 19.

There has never been such a thing as one Franconian language. The Franks spoke different languages.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Milis, L.J.R., "A Long Beginning: The Low Countries Through the Tenth Century" in J.C.H. Blom & E. Lamberts History of the Low Countries, pp. 6–18, Berghahn Books, 1999. ISBN 978-1-84545-272-8.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 de Vries, Jan W., Roland Willemyns and Peter Burger, Het verhaal van een taal, Amsterdam: Prometheus, 2003, pp. 12, 21–27. On page 25: "…Een groot deel van het noorden van Frankrijk was in die tijd tweetalig Germaans-Romaans, en gedurende een paar eeuwen handhaafde het Germaans zich er. Maar in de zevende eeuw begon er opnieuw een romaniseringsbeweging en door de versmelting van beide volken werd de naam Franken voortaan ook gebezigd voor de Romanen ten noordern van de Loire. Frankisch of François werd de naam de (Romaanse) taal. De nieuwe naam voor de Germaanse volkstaal hield hiermee verband: Diets of Duits, dat wil zeggen "volks", "volkstaal". [At that time a large part of the north of France was bilingual Germanic/Romance, and for a couple of centuries Germanic held its own. But in the seventh century a wave of romanisation began anew and because of the merging of the two peoples the name for the Franks was used for the Romance speakers north of the Loire. "Frankonian/Frankish" or "François" became the name of the (Romance) language. The new name for the Germanic vernacular was related to this: "Diets"" or "Duits", i.e. "of the people", "the people's language"]. Page 27: "…Aan het einde van de negende eeuw kan er zeker van Nederlands gesproken worden; hoe long daarvoor dat ook het geval was, kan niet met zekerheid worden uitgemaakt." [It can be said with certainty that Dutch was being spoken at the end of the 9th century; how long that might have been the case before that cannot be determined with certainty.]

- ↑ van der Wal, M., Geschiedenis van het Nederlands, 1992 , p.

- ↑ U. T. Holmes, A. H. Schutz (1938), A History of the French Language, p. 29, Biblo & Tannen Publishers, ISBN 0-8196-0191-8

- ↑ Keller, R.E. (1964). "The Language of the Franks". Bulletin of the John Rylands Library of Manchester 47 (1): 101–122, esp. 122. Chambers, W.W.; Wilkie, J.R. (1970). A short history of the German language. London: Methuen. p. 33. McKitterick 2008, p. 318.

- ↑ Dekker 1998, pp. 245–247.

- ↑ Salmon, Thomas (1767). A new geographical and historical grammar: wherein the geographical part is truly modern; and the present state of the several kingdoms of the world is so interspersed, as to render the study of geography both entertaining and instructive (new ed.). Edinburgh: Sands, Murray, and Cochran, for J. Meuros. p. 147.

- ↑ Bethel, Slingsby (1681). The interest of the princes and states of Europe (2nd ed.). London: J.M. for John Wickins. pp. 152–153.

- ↑ Solling, Gustav (1863). Diutiska: an historical and critical survey of the literature of Germany, from the earliest period to the death of Göthe. London: Tübner. pp. 14–16.

- ↑ Adams, Ernest (1890). The elements of the English language. London: George Bell and Sons. p. 17.

- ↑ Vaughan, Robert; Allon, Henry (July 1, 1862). "The Science of Language". British Quarterly Review 36 (71): 218–220. In this review Vaughan and Allon are paraphrasing from Max Müller's Science of Language lecture series, German language, later translated and published in English.

- ↑ Strong, Herbert Augustus; Meyer, Kuno (1886). Outline of a history of the German language. London: Swan Sonnenschein, Le Bas & Lowrey. p. 68.

- ↑ Wright, Joseph (1888). An Old High-German primer. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 1.

- ↑ Breuker, Ph. H. (2007), "On the Course of Franciscus Junius' Germanic Studies, with Special Reference to Frisian", in Bremmer, Rolf H. Jr.; Van der Meer, Geart; Vries, Oebele, Aspects of Old Frisian Philology, Amsterdam Beiträge zur ãlteren Germanistik Bd. 31/32; Estrikken 69, Amsterdam: Rodopi, p. 44

- ↑ Ozment, Steven (2005). A mighty fortress: a new history of the German people. New York: HarperCollins. p. 49.

- ↑ Müller, F Max (1891). The science of language, founded on lectures delivered at the Royal institution in 1861 and 1863. New York: C. Scribner's sons. pp. 247–248.

- ↑ Dekker 1998, pp. 255–256.

- ↑ Brandt, Gerard; Childe, John (Translator) (1721). The history of the Reformation and other ecclesiastical transactions in and about the Low-countries: from the beginning of the eighth century, down to the famous Synod of Dort, inclusive. In which all the revolutions that happen'd in church and state, on account of the divisions between the Protestants and Papists, the Arminians and Calvinists, are fairly and fully represented. Vol II. London: T. Wood. p. 346.

- ↑ Besides modern loan words, English also influenced French in earlier times, with Old English for example replacing the Latin words for the four cardinal directions: nord "north", sud "south", est "east" and ouest "west".

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/508379/Romance-languages/74738/Vocabulary-variations?anchor=ref603727

- ↑ See a list of Walloon names derived from Old Franconian.

- ↑ CNRTL, "escrime"

- ↑ http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/cali003nieu01_01/cali003nieu01_01_0025.php (entry: Vrank)

- ↑ Because the expected outcome of *aliso is *ause, this word is sometimes erroneously attributed to a Celtic cognate, despite the fact that the outcome would have been similar. However, while a cognate is seen in Gaulish Alisanos "alder god", a comparison with the treatment of alis- in alène above and -isa in tamis below should show that the expected form is not realistic. Furthermore, the form is likely to have originally been dialectal, hence dialectal forms like allie, allouche, alosse, Berrichon aluge, Walloon: al'hî, some of which clearly point to variants like Gmc *alūsó which gave MHG alze (G Else "whitebeam").

- ↑ Webster's Encyclopedic Unabridged Dictionary of the English Language, s.v. "bastard" (NY: Gramercy Books, 1996), 175: "[…] perhaps from Ingvaeonic *bāst-, presumed variant of *bōst- marriage + OF[r] -ard, taken as signifying the offspring of a polygynous marriage to a woman of lower status, a pagan tradition not sanctioned by the church; cf. OFris bost marriage […]". Further, MDu had a related expression basture "whore, prostitute". However, the mainstream view sees this word as a formation built off of OFr fils de bast "bastard, lit. son conceived on a packsaddle", very much like OFr coitart "conceived on a blanket", G Bankert, Bänkling "bench child", LG Mantelkind "mantle child", and ON hrísungr "conceived in the brushwood". Bât is itself sometimes misidentified as deriving from a reflex of Germanic *banstis "barn"; cf. Goth bansts, MDu banste, LG dial. Banse, (Jutland) Bende "stall in a cow shed", ON báss "cow stall", OE bōsig "feed crib", E boose "cattle shed", and OFris bōs- (and its loans: MLG bos, Du boes "cow stall", dial. (Zeeland) boest "barn"); yet, this connection is false.

- ↑ ML boscus "wood, timber" has many descendants in Romance languages, such as Sp and It boscoso "wooded." This is clearly the origin of Fr bois as well, but the source of this Medieval Latin word is unclear.

- ↑ etymologiebank.nl "bruin"

- ↑ Rev. Walter W. Skeat, The Concise Dictionary of English Etymology, s.v. "dance" (NY: Harper, 1898), 108. A number of other fanciful origins are sometimes erroneously attributed to this word, such as VL *deantiare or the clumsy phonetic match OLFrk *dintjan "to stir up" (cf. Fris dintje "to quiver", Icel dynta "to convulse").

- ↑ Webster's Encyclopedic, s.v. "screen", 1721. This term is often erroneously attached to *skermo (cf. Du scherm "screen"), but neither the vowel nor the m and vowel/r order match. Instead, *skermo gave OFr eskirmir "to fence", from *skirmjan (cf. OLFrk bescirman, Du beschermen "to protect", comp. Du schermen "to fence").

- ↑ Nieuw woordenboek der Nederlandsche taal By I.M. Calisch and N.S. Calisch.

- ↑ unsure etymology, debatable. The word frank as "sincere", "daring" is attested very late, after the Middle Ages. The word does not occur as such in Old Dutch or OHG. "Frank" was used in a decree of king Childeric III in the sense of free man as opposed to the native Gauls who were not free. The meaning 'free' is therefore debatable.

- ↑ Le Maxidico : dictionnaire encyclopédique de la langue française, s.v. "frapper" (Paris: La Connaissance, 1996), 498. This is worth noting since most dictionaries continue to list this word's etymology as "obscure".

- ↑ "etymologiebank.nl" ,s.v. "war" "chaos"

- ↑ "etymologiebank.nl" ,s.v. "wirwar"

- ↑ Gran Diccionari de la llengua catalana, s.v. "guinda", .

- ↑ http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=hauberk

- ↑ http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=garden&searchmode=none

- ↑ http://www.etymologiebank.nl/trefwoord/gaard1

- ↑ C.T. Onions, ed., Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, s.v. "mason" (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), 559. This word is often erroneously attributed to *makjo "maker", based on Isidore of Seville's rendering machio (c. 7th c.), while ignoring the Reichenau Glosses citing matio (c. 8th c.). This confusion is likely due to hesitation on how to represent what must have been the palatalized sound [ts].

- ↑ etymologiebank.nl noord

- ↑ Jean Dubois, Henri Mitterrand, and Albert Dauzat, Dictionnaire étymologique et historique du français, s.v. "osier" (Paris: Larousse, 2007).

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 etymologiebank.nl "poot"

- ↑ Onions, op. cit., s.v. "pad", 640.

- ↑ Skeat, op. cit., s.v. "patois", 335.

- ↑ Onions, op. cit., s.v. "seize", 807.

External links

- Gotische Runeninschriften (photo of Bergakker scabbard)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||