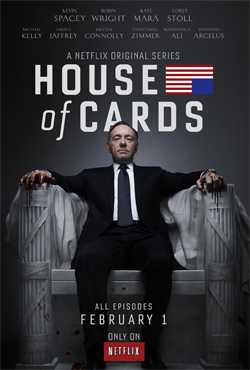

Frank Underwood (House of Cards)

| Frank Underwood | |

|---|---|

| House of Cards character | |

|

Kevin Spacey as Frank Underwood | |

| First appearance | "Chapter 1" |

| Created by | Beau Willimon |

| Portrayed by | Kevin Spacey |

| Information | |

| Full name | Francis James Underwood |

| Occupation |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina's 5th congressional district (Season 1) House Majority Whip (Season 1) Vice President of the United States (Season 2) President of the United States (Season 2–present) |

| Title | Juris Doctor |

| Spouse(s) | Claire Underwood |

| Religion | None[1] |

| Party | Democratic |

| Hometown | Gaffney, South Carolina |

| Alma mater | The Sentinel, Harvard Law School |

| Source | Francis Urquhart |

Francis Joseph "Frank" Underwood is a fictional character and the protagonist of the Netflix web television series House of Cards, played by Kevin Spacey. He is a variation of Francis Urquhart, the protagonist of the British novel and television series House of Cards, from which the American Netflix series is adapted. He is married to Claire Underwood (Robin Wright), but also had a sexual relationship with Zoe Barnes (Kate Mara) in season 1. He made his first appearance in the series' pilot episode, "Chapter 1".

Underwood is from Gaffney, South Carolina. He graduated from The Sentinel, a fictionalized version of The Citadel, The Military College of South Carolina, and Harvard Law School. Some of Underwood's dialogue throughout the series is presented in a direct address to the audience, a narrative technique that breaks the fourth wall. The character speaks in a Southern dialect. During season 1, he is the Democratic Majority Whip in the United States House of Representatives. In season 2, he is the newly appointed Vice President of the United States, before becoming President of the United States in the season finale.

The character has been described as manipulative, conniving, Machiavellian, and even evil and homicidal, while receiving significant critical praise as one of 21st century television's antiheroes. Spacey shared the distinction of being among the first three leading web television roles to be nominated for Primetime Emmy Awards when the 65th Primetime Emmy Awards were announced on July 18, 2013. Spacey's portrayal of Underwood is the only one of those three to earn a Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series nomination. Spacey has also been nominated for two Golden Globe Awards, winning one, and three Screen Actors Guild Awards, including one cast nomination and including one win, for his performance.

Background and description

Underwood's hometown is Gaffney, South Carolina.[2] He graduated from The Sentinel—a fictionalized version of The Citadel, The Military College of South Carolina—and Harvard Law School. He speaks in a southern dialect.[3][2][4] Underwood's great-great-great grandfather was fictional Corporal Augustus Elijah Underwood, who died at the age of 24 serving the 12th Regiment of McGowan's Brigade at the Bloody Angle engagement in the American Civil War. Underwood's great-great grandfather was 2 when his father was killed.[5] Publicly, Underwood speaks fondly of his father, who died at age 43 of a heart attack,[6] as a political ploy; in reality, he hardly knew his father, and did not think much of him.[7] Nonetheless, he was influenced by his father.[8] In Season 2's finale, he says that, at the age of thirteen, he walked in on his father putting a shotgun in his mouth, and that his father asked him to pull the trigger. Underwood says that his biggest regret is that he did not do it, as his father's alcoholism and abuse caused the family several more years of misery.[9]

Much of Underwood's dialogue throughout the series is presented in a direct address to the audience, a narrative technique that breaks the fourth wall.[10] Immediately prior to starring in House of Cards, Spacey had starred in a production of William Shakespeare's Richard III as Richard III of England,[10][11] a character that serves as a partial basis for both Urquhart and Underwood.[12] He may have been named by the show's creators after Oscar Underwood, who served as the first Democratic House Minority Whip from about 1900 to 1901.[13] Among his few vices are smoking cigarettes. He has a hobby of playing video games;[14] when his online gaming service becomes unavailable after he becomes Vice President, he takes up creating model figurines.

Spacey viewed portraying Underwood for a second season as a continuing learning process. "There is so much I don’t know about Francis, so much that I'm learning... I've always thought that the profession closest to that of an actor is being a detective... We are given clues by writers... Then you lay them all out and try to make them come alive as a character who’s complex and surprising, maybe even to yourself."[15]

Underwood's sexuality is ambiguous throughout much of the first two seasons; he has sexual liaisons with both men and women, but he is never explicitly identified as gay or bisexual. Before Season 2, various sources speculated about his homosexuality. The New York Times blog review of "Chapter 8" notes that he had a one semester experience with homosexuality in college.[16] According to David Carr and Ashley Parker, although it is unclear how his youthful homosexual experience influenced his choices, we never see Frank and Claire have sex in season 1.[16] Slate journalist Hanna Rosin notes that, if Frank and Claire Underwood were a real-life Washington couple and they were found each to be having an affair, Frank would be accused of being "secretly gay, turned on by women only when he can use them for a pure power play".[17] Other sources make no definite stance on Underwood's sexuality, but hypothesize that he is not sexually attracted to Claire.[18] In season 2, Frank is involved in a threesome with his wife and male Secret service agent Edward Meechum (Nathan Darrow),[19] while in season 3 there is a moment of sexual tension between Frank and his biographer, Tom Yates (Paul Sparks).[20]

Underwood vs. Urquhart

Underwood is an Americanized version of the original BBC character Francis Urquhart, a Machiavellian post-Margaret Thatcher Chief Whip of the Conservative Party. Urquhart employs deceit, cunning, murder, and blackmail to influence and pursue the office of Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. According to series producer Beau Willimon, the name change stemmed from the "Dickensian" feeling and "more legitimately American" sounding resonance of the name Underwood. Whereas Urquhart is an aristocrat by birth, Underwood is a self-made man.[21] Urquhart was one of television's first antiheroes,[12] whereas Underwood follows the more recent rash of antiheroes that includes Tony Soprano of The Sopranos, Walter White of Breaking Bad, and Dexter Morgan of Dexter.[11] However, unlike most other antiheroes, Underwood is not forced into immorality either by circumstance (White), birth (Soprano) or upbringing (Morgan). In his review of Season 2, Slant Magazine 's Alan Jones writes that Underwood is evil by choice.[22] Although the character is based on the BBC show's lead character, in interviews during the writing and filming of season 2, creator and showrunner Willimon said that he used Lyndon B. Johnson as a source of themes and issues addressed in House of Cards.[23] Unlike the right-leaning Urquhart, who is affiliated with the Conservative Party, the centrist Underwood is a member of the Democratic Party, but cares little for ideology in favor of "ruthless pragmatism" in furthering his own political influence and power.[2]

Relationships with Claire

Stelter described Frank and Claire Underwood as a "scheming" couple.[24] Michael Dobbs compares the compelling nature of their relationship favorably to the characters in the original British show and likens them to Macbeth and Lady Macbeth.[12] Frank has strong feelings for Claire, and frequently plots with her at night. He says "I love that woman, I love her more than sharks love blood."[25] While Frank is Machiavellian, Claire, like Lady Macbeth, encourages her husband to do whatever is necessary to seize power.[26][27] Hank Stuever of The Washington Post describes her as an ice-queen wife.[28] She encourages his vices while noting her disapproval of his weakness, saying, "My husband doesn’t apologize... even to me."[27] Her overt encouragement gives a credibility to their symbiosis.[29] Smith says "The Underwoods have proven themselves almost robotic in their pursuit of power."[30] Upon viewing a four-episode preview of season 2, Goodman says the series "...sells husband and wife power-at-all-costs couple...as a little too oily and reptilian for anyone's good."[31] Willimon notes that "What's extraordinary about Frank and Claire is there is deep love and mutual respect, but the way they achieve this is by operating on a completely different set of rules than the rest of us typically do."[32] Los Angeles Times critic Mary McNamara makes the case that House of Cards is a love story on many levels, but most importantly between Frank and Claire. It is a story about a man who will commit almost any crime imaginable while in pursuit of power and a political wife who gives him the encouragement to pursue that power.[33]

Relationships with Zoe

Underwood develops an intimate relationship with reporter Zoe Barnes (Kate Mara), with Claire's knowledge.[21] Stuever notes that as the show begins, Barnes is desperate to rise from covering the "Fairfax County Council" beat to covering "'what's behind the veil' of power in the Capitol hallways."[28] Stanley notes that by the end of the first episode, Mara's Barnes is among the cadre of Frank's accomplices. They begin a relationship, with Zoe promising to earn his trust and not "ask any questions" in return for his supplying her with sensitive political information.[27] Toward the end of Season 1, she ends their personal relationship and begins investigating his connection to Congressman Peter Russo's apparent suicide (Underwood had in fact murdered him).[30] Frank ultimately kills Zoe in the season 2 premiere, by pushing her in front of an oncoming subway train, after she begins to follow clues related to the murder.[34]

Breaking the Fourth Wall

Spacey summed up Underwood's relationship with the viewer - i.e. whenever he breaks the fourth wall - as being like that of a "best friend" and "the person [he trusts] more than anyone."[35] Indeed, Underwood's constant asides to the camera serve as a reminder of his intentions, and usually reveal his actual opinions on people that he is interacting with - he may, in one instance, smile to one of his colleagues' faces, but then tell the viewer of the disgust he feels for that individual. In this sense, the viewer serves as Frank's closest confidante over the course of the series. During these asides, he will try and justify his actions and address moral qualms or concerns the viewer may have - in the season 2 premiere, after having gone the whole episode without doing so, Frank addresses the viewer directly, and immediately brings up his recent murder of Zoe Barnes, justifying himself by saying that she would have just become a thorn in his side later. In addition, in season 3, after an argument with Claire that ends with her storming out on him, he looks directly at the viewer and snaps, "What're you lookin' at?"

Season 1

"Power is a lot like real estate. It’s all about location, location, location. The closer you are to the source, the higher your property value."

Underwood is a Democratic Majority Whip in the United States House of Representatives representing South Carolina's 5th congressional district since 1990.[2][36][37]

Underwood is passed over for an appointment as United States Secretary of State even though he had been promised the position after ensuring the election of United States President Garrett Walker (Michel Gill). Presidential Chief of Staff Linda Vasquez (Sakina Jaffrey) gives him this news prior to the January 2013 United States presidential inauguration. With the aid of Claire and his Chief of Staff Doug Stamper (Michael Kelly), Underwood uses his position as House Whip to seek retribution. He quickly allies with reporter Zoe Barnes (Kate Mara), whom he uses to undermine his rivals via the press, and begins manipulating Pennsylvania Rep. Peter Russo (Corey Stoll), whom he eventually murders as part of his plan. The viciousness of Underwood's manipulations escalates over the course of the season.[11] In the season finale, "Chapter 13", he is appointed Vice President to replace Jim Matthews (Dan Ziskie), whom he had manipulated into resigning earlier in the season.

According to Time television critic James Poniewozik, by the end of the first episode, it becomes clear that Underwood both literally and figuratively uses meat as his metaphor of choice. He may begin a day with a celebratory rack of ribs, because "I’m feelin’ hungry today!", and he depicts his life with meat metaphors. For example, he describes the White House Chief of Staff with grudging admiration: "She’s as tough as a two-dollar steak", and plans to destroy an enemy the way "you devour a whale. One bite at a time". He also endures a tedious weekly meeting with House leaders, as he tells the audience, by "[imagining] their lightly salted faces frying in a skillet."[29]

Season 2

"There are two types of vice presidents: doormats and matadors. Which do you think I intend to be?"

Underwood assumes the position of Vice President of the United States. Tim Goodman of The Hollywood Reporter notes that with his new position "he's got more power now and that means he instills more fear in his enemies".[31] At one point during the season, he states "The road to power is paved with hypocrisy and casualties. I need to prove what the vice president is capable of."[38] Frank and Claire "continue their ruthless rise to power as threats mount on all fronts."[39] Over the course of the season, Underwood "faces challenges from similarly ambitious businessmen, the Chinese government and Congress itself" as he continues to pursue his political aspirations.[40] His plotline revolves around battles with billionaire Raymond Tusk (Gerald McRaney), involving Chinese money laundering. Over the course of the season his biggest challenges are the institutional power of the Office of the President and Tusk's power as a billionaire industrialist.[41]

According to Sara Smith of The Kansas City Star, Underwood fails to break the fourth wall as he had done throughout the first season until the end of the first episode in this season, when he finally asks the audience "Did you think I’d forgotten you? Perhaps you hoped I had."[30] Subsequently, Underwood begins with his trademark fourth wall statements beginning with "For those of us climbing to the top of the food chain, there can be no mercy. There is but one rule: Hunt or be hunted."[30] He finds new rivals in Tusk, who seeks to replace him as Walker's right-hand adviser, and his former communications director, Remy Danton (Mahershala Ali), who is now a lobbyist working with Tusk.[30]

At the beginning of the season, Underwood is trying to erase all links to Russo's death.[42] Thus, he kills Barnes by shoving her in front of an oncoming Washington Metro train.[43] Another early task for newly promoted Underwood is finding his own replacement as House Majority Whip. He supports Jacqueline Sharp (Molly Parker), a military veteran and third-term Representative from California, although he refrains from offering public backing.[44]

Toward the end of the season, Underwood orchestrates Walker's downfall. He secretly leaks the details of the money laundering, for which Walker is blamed. While publicly supporting Walker, Underwood works behind the scenes to have him impeached, with Sharp's help. In the season finale, "Chapter 26", Walker resigns, and Underwood succeeds him as President of the United States.

Frank and Claire engage in a threesome during the season, but have otherwise largely given up intramarital and extramarital sex in favor of their pursuit of power. International Business Times critic Ellen Killoran notes that this may relate back to Frank's quotation of Oscar Wilde in Season 1: "A great man once said, everything is about sex. Except sex. Sex is about power." Avoiding sex may retain the balance of power in their relationship.[45] His relationship with Claire is the epicenter of season 2.[46]

Season 3

"When they bury me, it won't be in my backyard, and when they come to pay their respects, they'll have to wait in line."

Season begins with Frank's presidency off to a rocky start: six months into his term, he is unpopular with the public, and Congress is blocking his attempts to move legislation forward. He plans to secure his legacy with an ambitious jobs bill, America Works, but the Democratic Congressional leadership refuses to support it; they also tell him that they will not support him if he seeks the presidential nomination in the next election. To make matters worse, Claire's run for a United Nations post is defeated after she makes a gaffe during a Senate nomination hearing. Frank then announces that he will not run for president, and advocates for the jobs bill, which he intends to pay for by stripping entitlement programs. He fails to get the jobs bill through Congress and uses that as a reason to renege on his promise to not run in 2016. Solicitor General Heather Dunbar announces that she will seek the presidential nomination, and actually gives Frank a battle. Frank convinces Jackie Sharp to get married so she can announce her candidacy, for the sole reason of sapping women’s votes from Dunbar, at which point she will withdraw and accept the nomination for VP. After the presidential debate, where Frank attacks Dunbar and Sharp, she announces her withdrawal from the race, and gives her support to Dunbar. Ultimately, however, Frank wins the Iowa caucuses.

Meanwhile, the Underwoods' marriage is faltering. Frank gives Claire the ambassador job in a recess appointment, but she is forced to resign in order to solve a diplomatic crisis. Claire begins to question whether she still loves Frank, and they get into an ugly fight in which Frank tells her that she is nothing without him. Season 3 ends with Claire leaving Frank as he prepares for the New Hampshire primary.[48]

Critical response

Season 1

The New York Times' David Itzkoff called Underwood a "scheming politician" who does "some of the most evil and underhanded things imaginable".[49] Brian Stelter of The New York Times said Underwood "…is on a quest for power that’s just as suspenseful as anything on television."[4] New York Daily News critic Don Kaplan says "…conniving Congressman Frank Underwood, is easily one of the most complex antiheroes on TV — except he’s not on TV".[50] David Wiegand of the San Francisco Chronicle describes the character as one who "all but salivates over the chance to use his considerable power to gain more power, especially if it involves pulling the rug out from under some colleagues and the wool over the eyes of others."[51]

Director David Fincher describes the character as a "Machiavellian taking you under his wing and walking you through the corridors of power, explaining the totally mundane and crass on a mechanical level to the most grotesque manipulations of a system that is set up to have all these checks and balances".[21] Beau Willimon describes him as "remorselessly self-interested, desiring power for power's sake".[12] Andrew Davies, the producer of the original UK TV series, feels that Underwood lacks the "charm" of the original character, Francis Urquhart.[21]

The Independent praised Spacey's portrayal as a more "menacing" character, "hiding his rage behind Southern charm and old-fashioned courtesy,"[12] while The New Republic noted that "When Urquhart addressed the audience, it was partly in the spirit of conspiratorial fun. His asides sparked with wit. He wasn't just ruthlessly striving, he was amusing himself, mocking the ridiculousness of his milieu. There is no impishness about Spacey’s Frank Underwood, just numb, machine-like ambition. Even his affection for his wife is a calculation."[11]

Poniewozik praises Underwood's accent, saying "Spacey gives Underwood a silky Southern accent you could pour over crushed ice and sip with a sprig of mint on Derby Day."[29] Nancy deWolf Smith of The Wall Street Journal describes the accent as a "mild but sometimes missing Carolina accent".[25] Time listed Frank Underwood among the 11 most influential fictional characters in 2013.[52]

According to Salon 's David Sirota, by making Underwood a liberal rather than a conservative "'House of Cards' is avoiding the standard cartoonish portrayal of Washington as a place of Evil-And-Powerful Conservatives and Idealistic-But-Powerless Liberals. Instead, it is more honestly admitting that in many cases, both parties’ leaders are equally vicious, powerful and corrupt."[2]

Spacey says he followed the real life House Majority Whip Kevin McCarthy in order to add realism to his portrayal. He also claims that the portrayal of a Congress that is efficient and effective is both enviable and realistic.[53]

Season 2

According The Kansas City Star 's Smith, "Frank hasn’t changed, and neither has his brand of Machiavellian political theater" and "Spacey has lost none of his smarmy magnetism as the cartoonish villain".[30] According to Variety 's Brian Lowry, "Kevin Spacey’s showy performance as an unscrupulous politician" is foremost among the show's strengths, but the show's weakness is the "failure to present its scheming protagonist with equally matched foes".[54] Lowry feels that as conniving as Underwood is, it is unfathomable that "nobody else in a town built on power seems particularly adept at recognizing this or combating him".[54] Goodman says "Spacey is nothing if not constantly magnetic".[31] The delayed use of the fourth wall is perceived as clever.[31] Alison Willmore of Indiewire says that "Unlike Walter White or Tony Soprano, Frank feels at peace with his ruthless pragmatism and what he does in pursuit of power, and reminds us of the fact in his asides to the camera...he may be a ruthless sociopath, but there's something to admire there".[55] However Willmore noted that Frank became lighter in season 2 noting that the season was "...delivered with more of a wink by Frank than before."[55]

Poniewozik notes that "It also remains a delight to watch Spacey pump the humid breath of life into House of Cards’ arid Capitol chill. If only his character weren’t so dominant of his surroundings as well. One reason the series’ movements can feel so mechanical is that, so far, no one seems nearly in Underwood’s league: not the adversaries he battles directly, nor the sad sacks that he gulls without their even knowing it."[14] Chuck Barney of the San Jose Mercury News notes that the preview episodes show that "Frank's "Survivor"-like back-stabbing is beginning to feel a bit repetitive." and that his lack of an adversarial foil has become an issue: "...things always seem to fall neatly into place for him. Even his showdowns with the president (Michel Gill) come off as one-sided..."[56] Verne Gay of Newsday notes that "Frank Underwood has no remorse, no superannuated sense of Washington tradition or decorum, and certainly no second thoughts. He is TV's perfect monster of the moment - a compleat malefactor, with a pleasing honey-toned drawl."[57]

Alessandra Stanley of The New York Times says "By positing a Johnsonesque power broker and master schemer who wields cabalistic influence behind the scenes, House of Cards assigns order and purpose to what, in real life, is too often just an endless, baffling tick-tack-toe stalemate."[58] NPR's Eric Deggans says that Underwood "blends velvety charm and mesmerizing menace like no other character on television".[59]

New York Observer critic Drew Grant notes that although the series aired during the golden age of dramatic antiheroes, Underwood's villainy has become trite: "House of Cards is a good reminder, however, that there is a reason Iago wasn’t the center of Othello. Unrelenting, unexplained cruelty can be as pedantic as constant kindness."[60]

Awards and nominations

At the 3rd Critics' Choice Television Awards, Spacey was nominated for Best Actor in a Drama Series for his portrayal of Underwood.[61]

On July 18, 2013, Netflix earned the first Primetime Emmy Award nominations for original online only web television for the 65th Primetime Emmy Awards. Three of its web series, Arrested Development, Hemlock Grove, and House of Cards, earned nominations.[24] For the first time, three Primetime Emmy nominations for lead roles were from web television series: Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series to Spacey for his portrayal of Frank Underwood, Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series to Robin Wright for her portrayal of Claire Underwood, and Outstanding Lead Actor in a Comedy Series to Jason Bateman for his portrayal of Michael Bluth in Arrested Development.[24] Spacey submitted "Chapter 1" for consideration to earn his nomination.[62] Spacey also earned a Golden Globe nomination for Best Actor in a Television Series Drama and a Screen Actors Guild nomination for Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Drama Series nominations.[63][64]

In season 2, Spacey won the Golden Globe for Best Actor in a Television Series Drama at the 72nd Golden Globe Awards and Screen Actors Guild Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Drama Series at the 21st Screen Actors Guild Awards, as well as nominations for Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series at the 66th Primetime Emmy Awards and a Screen Actors Guild nomination for Outstanding by an Ensemble in a Drama Series.[65][66][67][68][69]

Notes

- ↑ Congressional Prayer. Youtube.com. 2014-02-13. Retrieved 2014-06-14.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Sirota, David (March 12, 2013). "Why was Francis Underwood a Democrat?". Salon. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ↑ Abad-Santos, Alex (February 27, 2015). "What linguists say about Kevin Spacey's bizarre Southern accent on House of Cards". Vox. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Stelter, Brian (January 18, 2013). "A Drama’s Streaming Premiere". The New York Times. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ↑ House of Cards (U.S. TV series) [House of Cards (season 2)] (Streaming video). Chapter 18, 29:10 remaining: Netflix. 2014. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- ↑ House of Cards (U.S. TV series) [House of Cards (season 1)] (Streaming video). Chapter 3, 20:05 remaining: Netflix. 2013. Retrieved 2014-03-16.

- ↑ Couch, Aaron (2014-02-13). "'House of Cards': Frank Underwood's 10 Most Ruthless Moments (Poll)". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2014-03-16.

- ↑ Busis, Hillary (2014-02-18). "'House of Cards': Let's talk all of season 2". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2014-03-16.

- ↑ Jeffries, Stuart (2014-03-05). "House of Cards recap, series two, episode 13 – 'Cut out his heart and put it in his hands'". The Guardian. Retrieved 2014-03-16.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Cornet, Roth (January 31, 2013). "Netflix's Original Series House of Cards -- From David Fincher and Kevin Spacey -- May be the New Face of Television". IGN. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Bennett, Laura (February 5, 2013). "Kevin Spacey's Leading-Man Problem The star of the 13-hour "House of Cards" is as impenetrable as ever". New Republic. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Hughes, Sarah (January 30, 2013). "'Urquhart is deliciously diabolical': Kevin Spacey is back in a remake of House of Cards". The Independent. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ↑ McCormack, Kirsty (2014-02-14). "Kate Mara steals the show at 'House of Cards' season premiere in sexy cut-out dress". Daily Express. Retrieved 2014-12-26.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Poniewozik, James (2014-02-12). "Review: House of Cards Returns for Season Two: Kevin Spacey's D.C. power play still has cynical bite, but some old problems remain.". Time. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- ↑ Moore, Frazier (2014-02-12). "Kevin Spacey dealing Season 2 of 'House of Cards'". Boston.com. Associated Press. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Carr, David and Ashley Parker (March 21, 2013). "‘House of Cards’ Recap, Episode 8: You Can Go Home Again, It Just Might Get Complicated". The New York Times. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ↑ Rosin, Hanna (March 18, 2013). ""More Than Sharks Love Blood": Do Frank and Claire Underwood have the ideal marriage?". Slate. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ↑ McGee, Ryan (March 22, 2013). "House Of Cards: "Chapter 8"". The A.V. Club. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ↑ Dockterman, Eliana (2014-02-17). "The 9 Most Shocking Moments from House of Cards Season 2". Time. Retrieved 2014-02-18.

- ↑ House of cards, Season 3, Episode 10, "Chapter 36"

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Lacob, Jace (January 30, 2013). "David Fincher, Beau Willimon & Kate Mara On Netflix’s ‘House of Cards’". The Daily Beast. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ↑ Jones, Alan (2014-02-18). "House of Cards: Season Two". Slant Magazine. Retrieved 2014-03-14.

- ↑ Leopold, Todd (August 28, 2013). "'House of Cards' creator Beau Willimon plays a solid hand". CNN. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Stelter, Brian (July 18, 2013). "Netflix Does Well in 2013 Primetime Emmy Nominations". The New York Times. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 deWolf Smith, Nancy (January 31, 2013). "Fantasies About Evil, Redux". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Ostrow: Kevin Spacey shines in "House of Cards" political drama on Netflix". The Denver Post. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Stanley, Alessandra (January 31, 2013). "Political Animals That Slither: ‘House of Cards’ on Netflix Stars Kevin Spacey". The New York Times. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Stuever, Hank (January 31, 2013). "‘House of Cards’: Power corrupts (plus other non-breaking news)". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Poniewozik, James (January 31, 2013). "Review: House of Cards Sinks Its Sharp Teeth into Washington". Time. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 30.6 Smith, Sara (2014-02-07). "Second season of ‘House of Cards’ is a vote for vice". The Kansas City Star. Retrieved 2014-02-09.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 Goodman, Tim (2014-02-03). "House Of Cards: TV Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ↑ Oldenburg, Ann (2014-02-13). "'House of Cards' promises more 'plotting and scheming'". USA Today. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- ↑ McNamara, Mary (2014-02-14). "Review: 'House of Cards' plays new hand with brutal, clear resolve". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ D'Addario, Daniel (2014-02-15). "Yes, that really just happened on "House of Cards"". Salon. Retrieved 2014-02-18.

- ↑ http://www.bustle.com/articles/14708-house-of-cards-kevin-spacey-isnt-talking-to-you-when-he-speaks-into-camera

- ↑ Blake, Aaron (December 17, 2013). "Obama wishes D.C. worked more like it does in ‘House of Cards’". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ Plumb, Terry (September 29, 2013). "Humble pie on the menu". The Herald. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ Lewis, Hilary (December 13, 2013). "'House of Cards' Season 2 Trailer: The Threats and Power Grabs Mount (Video)". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ Blake, Meredith (December 4, 2013). "Netflix sets premiere date for 'House of Cards' Season 2". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- ↑ Welshman, Tom (2014-03-18). "TV Review – House of Cards, Season 2". Impact. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

- ↑ VandenDolder, Tess (2014-02-17). "'House of Cards' Season 2 Review: Shocking and Messy, But Just as Addictive as Ever". In The Capital. Streetwise Media. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

- ↑ Zurawik, David (2014-02-08). "Season 2 of 'House of Cards' packs theatrical power". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2014-02-09.

- ↑ Hooton, Christopher (2014-02-18). "House of Cards season 2 shock twist was planned from day one, says showrunner". The Independent. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ↑ Smith, Sara (2014-02-07). "New season brings a formidable female player to ‘House of Cards’". The Kansas City Star. Retrieved 2014-02-09.

- ↑ Killoran, Ellen (2014-02-18). "'House of Cards' Season 2 Review: Burning Questions Remain After Netflix Binge". International Business Times. Retrieved 2014-03-17.

- ↑ Woods, Baynard (2014-02-26). "Review: House of Cards Season 2: Francis Underwood gives liberals their own Dick Cheney: a vice president able to push through his agenda.". City Paper. Archived from the original on 2014-03-19. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ↑ Season 3, Episode 1, "Chapter 27"

- ↑ Season 3, Episode 13, "Chapter 39"

- ↑ Itskoff, Dave (July 18, 2013). "Emmy Nominees: Kevin Spacey of ‘House of Cards’". The New York Times. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ↑ Kaplan, Don (July 21, 2013). "Kevin Spacey and Netflix's 'House of Cards' receive Emmy nominations, signaling a new order in TV". New York Daily News. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ↑ Wiegand, David (January 30, 2013). "'House of Cards' review: Sexy political revenge". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ↑ Alter, Charlotte and Eliana Dockterman (December 9, 2013). "The 11 Most Influential Fictional Characters of 2013: These are the on-screen figures who got our attention: 6. Frank Underwood". Time. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ↑ Munsil, Leigh (2014-02-16). "Spacey: 'House of Cards' not far from reality". Politico. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Lowry, Brian (2014-01-31). "TV Review: ‘House of Cards’ – Season Two". Variety. Retrieved 2014-02-09.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Willmore, Alison (2014-02-05). "In Its Second Season, 'House of Cards' Brings Its D.C. Machinations to the Next Level". Indiewire. Retrieved 2014-02-11.

- ↑ Barney, Chuck (2014-02-11). "Review: 'House of Cards' returns for more political dirty deeds". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved 2014-02-11.

- ↑ Gay, Verne (2014-02-13). "'House of Cards' Season 2 review: A joyride". Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- ↑ Stanley, Alessandra (2013-02-13). "How Absolute Power Can Delight Absolutely: ‘House of Cards’ Returns, With More Dark Scheming". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-02-14.

- ↑ Deggans, Eric (2014-02-14). "Antihero Or Villain? In 'House Of Cards,' It's Hard To Tell". NPR. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ Grant, Drew (2014-02-17). "The Anhedonia of Antiheroes: Why House of Cards’ Second Season Isn’t as Fun as It Should Be". The New York Observer. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ "Big Bang, Horror Story, Parks & Rec, Good Wife, The Americans Lead Critics Choice Nominations". TVLine. May 22, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ↑ Riley, Jenelle (August 26, 2013). "Emmy Episode Submissions: Lead Actor in a Drama". Back Stage. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ↑ "SAG nominations 2014: The complete list of nominees". Los Angeles Times. December 11, 2013. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- ↑ Farley, Christopher John (December 12, 2013). "Golden Globes Nominations 2014: ’12 Years a Slave,’ ‘American Hustle’ Lead Field". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- ↑ "2014 Emmy Nominations: ‘Breaking Bad,’ ‘True Detective’ Among the Honored". New York Times. July 10, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ↑ Mitovich, Matt Webb (December 10, 2014). "SAG Awards: Modern Family, Thrones, Homeland, Boardwalk, Cards Lead Noms; Mad Men Shut Out; HTGAWM, Maslany and Aduba Get Nods". TVLine. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Mitovich, Matt Webb (December 11, 2014). "Golden Globes: Fargo, True Detective Lead Nominations; Jane the Virgin, Transparent Score Multiple Nods". TVLine. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ↑ "List: Who won Golden Globe awards". USA Today. Gannett Company. January 12, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ↑ Leeds, Sarene (January 26, 2015). "SAG Awards: The Complete 2015 Winners List". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

| ||||||||||||||