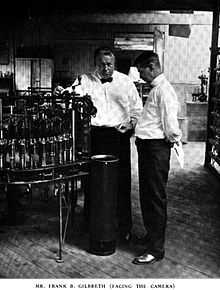

Frank Bunker Gilbreth, Sr.

| Frank Bunker Gilbreth, Sr. | |

|---|---|

Frank Bunker Gilbreth, Sr. | |

| Born |

July 7, 1868 Fairfield, Maine |

| Died |

June 14, 1924 (aged 55) Montclair, New Jersey |

| Employer | Purdue University |

| Spouse(s) | Lillian Moller Gilbreth (m. Oct. 19, 1904) |

| Children | Anne Gilbreth, Mary Gilbreth, Ernestine Gilbreth Carey, Martha Gilbreth, Frank Bunker Gilbreth, Jr., Bill Gilbreth, Lillian Gilbreth, Fred Gilbreth, Dan Gilbreth, Jack Gilbreth, Bob Gilbreth, Jane Gilbreth |

Frank Bunker Gilbreth, Sr. (July 7, 1868 – June 14, 1924) was an early advocate of scientific management and a pioneer of motion study, and is perhaps best known as the father and central figure of Cheaper by the Dozen. He and his wife Lillian Moller Gilbreth were themselves industrial engineers and efficiency experts who contributed to the study of industrial engineering in fields such as motion study and human factors.

Biography

Youth

Born in Fairfield, Maine, in 1868 to John Hiram and Martha (née Bunker) Gilbreth, Gilbreth had no formal education beyond high school. For a long time in New England, his father ran a hardware store. At age 3, his father died and his family moved to Boston, Massachusetts. After high school, he attained a job as a bricklayer apprentice and then became a building contractor, an inventor with several patents, and finally a management engineer. He eventually became an occasional lecturer at Purdue University, which houses his papers. He married Lillian Evelyn Moller on October 19, 1904, in Oakland, California; they had 12 children, 11 of whom survived him. Their names were Anne, Mary (1906–1912), Ernestine, Martha, Frank Jr., William, Lillian, Frederick, Daniel, John, Robert, and Jane.

Early career

Gilbreth discovered his vocation when, as a young building contractor, he sought ways to make bricklaying (his first trade) faster and easier. This grew into a collaboration with his wife, Lillian Moller Gilbreth, who studied the work habits of manufacturing and clerical employees in all sorts of industries to find ways to increase output and make their jobs easier. He and Lillian founded a management consulting firm, Gilbreth, Inc., focusing on such endeavors.

They were involved in the development of the design for the Simmons Hardware Company's Sioux City Warehouse. The architects had specified that hundreds of 20-foot (6.1 m) hardened concrete piles were to be driven in to allow the soft ground to take the weight of two million bricks required to construct the building. The "Time and Motion" approach could be applied to the bricklaying and the transportation. The building itself was also required to support efficient input and output of deliveries via its own railroad switching facilities.[1]

Motion studies

.ogv.jpg)

Gilbreth served in the U.S. Army during World War I. His assignment was to find quicker and more efficient means of assembling and disassembling small arms. According to Claude George (1968), Gilbreth reduced all motions of the hand into some combination of 17 basic motions. These included grasp, transport loaded, and hold. Gilbreth named the motions therbligs – "Gilbreth" spelled backwards with the th transposed. He used a motion picture camera that was calibrated in fractions of minutes to time the smallest of motions in workers.

George noted that the Gilbreths were, above all, scientists who sought to teach managers that all aspects of the workplace should be constantly questioned, and improvements constantly adopted. Their emphasis on the "one best way" and therbligs predates the development of continuous quality improvement (CQI),(George (1968, p. 98)) and the late 20th century understanding that repeated motions can lead to workers experiencing repetitive motion injuries.

Gilbreth was the first to propose the position of "caddy" (Gilbreth's term) to a surgeon, who handed surgical instruments to the surgeon as called for. Gilbreth also devised the standard techniques used by armies around the world to teach recruits how to rapidly disassemble and reassemble their weapons even when blindfolded or in total darkness.

Death

Gilbreth died of a heart attack on June 14, 1924, at age 55. He was at the Lackawanna railway station in Montclair, New Jersey, talking on a telephone. Lillian outlived him by 48 years.[2][3]

Legacy

Although the work of the Gilbreths is often associated with that of Frederick Winslow Taylor, there was a substantial philosophical difference between the Gilbreths and Taylor. The symbol of Taylorism was the stopwatch; Taylor was concerned primarily with reducing process times. The Gilbreths, in contrast, sought to make processes more efficient by reducing the motions involved. They saw their approach as more concerned with workers' welfare than Taylorism, which workers themselves often perceived as concerned mainly with profit. This difference led to a personal rift between Taylor and the Gilbreths which, after Taylor's death, turned into a feud between the Gilbreths and Taylor's followers. After Frank's death, Lillian Gilbreth took steps to heal the rift;[4] however, some friction remains over questions of history and intellectual property.[5]

In conducting their Motion Study method to work, they found the key to improving work efficiency was in reducing unnecessary motions. Not only were some motions unnecessary, but they caused employee fatigue. Their efforts to reduce fatigue not only included reducing motions, but tool design, parts placement, bench and seating height, for which they began to develop workplace standards.

If you were to review their standards alongside current knowledge in ergonomics, you would find many identical concepts. While never credited, the Gilbreths' work broke ground for our current understanding of ergonomics.[6]

Frank and Lillian Gilbreth often used their large family (and Frank himself) as guinea pigs in experiments. Their family exploits are lovingly detailed in the 1948 book Cheaper by the Dozen, written by son Frank Jr. and daughter Ernestine (Ernestine Gilbreth Carey). The book inspired two films of the same name – one (1950) starring Clifton Webb and Myrna Loy,[7] and the other (2003) starring comedians Steve Martin and Bonnie Hunt,[8] which bears no resemblance to the book, except that it features a family with twelve children, and the wife's maiden name is Gilbreth. A 1952 sequel, titled Belles on Their Toes, chronicled the adventures of the Gilbreth family after Frank's 1924 death. A later biography, Time Out For Happiness, was authored by Frank Jr. alone and published in 1971; it is out of print and considered rare.

See also

References

- ↑ "Historic Battery Building". hardrockcasinosiouxcity.com. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ "Maj. Frank B. Gilbreth.". Washington Post. June 15, 1924. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ↑ "Maj. Gilbreth Stricken With Heart Attack at Railway Station After Talking to His Wife.". Washington Post. June 15, 1924. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

Frank B. Gilbreth, 56 years old, known mechanical engineer and author, died of heart ... Gilbreth was born at Fairfield, Maine on July 7, 1868 and educated at Boston. ...

- ↑ Price 1990.

- ↑ The Gilbreth Network at gilbrethnetwork.tripod.com

- ↑ The Gilbreth Network at gilbrethnetwork.tripod.com

- ↑ Cheaper by the Dozen (1950) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Cheaper by the Dozen (2003) at the Internet Movie Database

Further reading

- The Magic of Motion Study

- George, C. S. (1968). The History of Management Thought. Prentice Hall.

- Gilbreth, Frank Jr., and Ernestine Gilbreth Carey, 1948. Cheaper by the Dozen. ISBN 0-06-008460-X

- Gilbreth, Frank Jr., 1950. Belles on Their Toes. ISBN 0-06-059823-9

- Lillian Moller Gilbreth, 1998. As I Remember. Norcross, GA: Engineering & Management Press.

- Price, B. (1990). "Frank and Lillian Gilbreth and the Motion Study Controversy, 1907-1930" (PDF). In Nelson, D. A Mental Revolution: Scientific Management since Taylor. Ohio State University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Frank Bunker Gilbreth. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Frank Bunker Gilbreth, Sr. |

- Gilbreth archive at Purdue University.

- The Gilbreth Network.

- Bibliography of books by and about Gilbreth.

- "The Gilbreth 'Bug-lights', by Frank B. Gilbreth, Jr. Originally published in the Historic Nantucket, Vol 39, no. 2 (Summer 1991), p. 20–22.

- Original Films of Frank B Gilbreth 1945

| ||||||||||||||||||

|