France–Thailand relations

|

|

France |

Thailand |

|---|---|

France–Thailand relations cover a period from the 16th century until modern times. Relations started in earnest during the reign of Louis XIV with numerous reciprocal embassies, and a major attempt by France to Christianize Siam (modern Thailand) and establish a French protectorate, which failed when the country revolted against foreign intrusions in 1688. France would only return more than a century and a half later as a modernized colonial power, engaging in a struggle for territory and influence against Thailand in the Indochinese Peninsula, which would last until the 20th century.

16th-17th century relations

First French Catholic missions

The first instance of France-Thailand contacts is also the first historical record of an attempt to introduce Christianity to Thailand: according to the Jesuit Giovanni Pietro Maffei, about 1550 a French Franciscan, Bonferre, hearing of the great kingdom of the Peguans and the Siamese in the East, went on a Portuguese ship from Goa to Cosme (Pegu), where for three years he preached the Gospel, but without any result.[1]

The first major contacts between the two countries occurred after Siam was made a vicariate apostolic by Pope Alexander VII on 22 August 1662. The mission was given to the newly formed Missions Etrangères de Paris (Paris Foreign Missions Society) to evangilize the Far-East, and Siam became the first country to receive these evangilization efforts, to be followed by new missions 40 years later in Cochinchina, Tonkin and parts of China,[2] because Siam was highly tolerant of other religions and was indeed the only country in Southeast Asia where the Catholic Fathers could establish themselves safely.[3]

Monseigneur Pierre Lambert de la Motte, Bishop of Berytus, Vicar-Apostolic of Cochinchina, and member of the Missions Etrangères de Paris, accompanied by Fathers De Bourges and Deydier,[4] left Marseilles on 26 November 1660, and reached Mergui in Siam 18 months later.[2] He arrived in Ayutthaya in 1662.[5]

In 1664, a group of missionaries, led by Monseigneur François Pallu, Bishop of Heliopolis, also of the Missions Etrangères de Paris, joined Mgr Lambert in the capital of Siam Ayutthaya after 24 months overland, and started missionary work.[2] In 1665-66 they built a seminary in Ayutthaya,[6] (the Seminary of Saint Joseph, later Seminary of the Holy Angels, at the origin of the College General now in Penang, Malaysia), with the approval of king Narai.

In 1669, Monseigneur Louis Laneau, Bishop of Metellopolis, also member of the Paris Foreign Missions Society, was nominated as head of a Roman Catholic mission in Indochina, with his headquarters at Ayutthaya.[5] They propagated the Christian faith and also took care of Annamite Christians and Japanese Christian communities in Siam.[4] The Siamese king Narai warmly welcomed these missionaries, providing them with land for a church, a mission-house and a seminary (St. Joseph's colony).[4] Bishops Lambert and Ballue established a Western hospital in Thailand in 1669 at Ayutthaya, with Father Laneau as the head doctor. The hospital provided medical care to about 200-300 people daily.[7]

During a passage in Europe in 1670, Mgr Pallu obtained from Louis XIV a letter to king Narai, which, together with a letter from the Pope, he remitted in Ayutthaya in October 1673 and which was received with great reverence.[8][9]

These contacts were closely associated with the development of French influence in Southern Asia, and especially with the establishment of the French East India Company in 1664, and the development of colonial French India.

First trade contacts (1680)

In 1680, the recently formed French East India Company sent a ship to Thailand, bearing a trading mission led by André Deslandes-Boureau, son-in-law of the Governor General of the French settlement in Pondicherry François Martin,[10] which received a good reception by the Thais.[11]

In September 1680, a ship from the French East India Company visited Phuket and left with a full cargo of tin. The Dutch, the English, and from the 1680s the French, competed with each other for trade with the island of Phuket (the island was named Junk Ceylon at that time), which was valued as a very rich source of tin. In 1681 or 1682, the Siamese king Narai, who was seeking to reduce Dutch and English influence, named Governor of Phuket the French medical missionary Brother René Charbonneau, a member of the Siam mission of the Société des Missions Etrangères. Charbonneau held the position of Governor until 1685.[12]

First Thai embassies to France (1680 and 1684)

The Thai king Narai further sought to expand relations with the French, as a counter-weight to Portuguese and Dutch influence in his kingdom, and at the suggestion of his Greek counsellor Constantine Phaulkon. In 1664, the Dutch had used force to exact a treaty granting them extraterritorial rights as well as freer access to trade. In 1680, a first Siamese ambassador to France was sent in the person of Phya Pipatkosa on board the Soleil d'Orient, but the ship was wrecked off the coast of Africa after leaving Mauritius and he disappeared.[5][11]

A second embassy was sent to France in 1684 (passing through England), led by Khun Pijaiwanit and Khun Pijitmaitri, requesting the dispatch of a French embassy to Thailand.[5] They met with Louis XIV in Versailles. In response, Louis XIV sent an embassy led by the Chevalier de Chaumont.

Embassy of Chevalier de Chaumont (1685)

The Chevalier de Chaumont was the first French ambassador for King Louis XIV in Siam. He was accompanied on his mission by Abbé de Choisy, the Jesuit Guy Tachard, and Father Bénigne Vachet of the Société des Missions Étrangères de Paris. At the same time, he returned to Siam the two ambassadors of the 1684 First Siamese Embassy to France.[13]

Lastly, the Chevalier de Chaumont brought a group of Jesuit mathematicians (Jean de Fontaney (1643–1710), Joachim Bouvet (1656–1730), Jean-François Gerbillon (1654–1707), Louis Le Comte (1655–1728) and Claude de Visdelou (1656–1737))[14] whose mission was to continue to China to reach the Jesuit China missions. Le Comte would remain in Siam besides King Narai, but the others would reach China in 1687.

The Chevalier de Chaumont tried without success to convert King Narai the Great to Catholicism and to conclude significant commercial treaties. A provisional agreement was signed to facilate trade between France and the Royal Warehouse Department. France also received a tin monopoly in Phuket, with Chaumont's former maître d'hôtel Sieur de Billy named governor of the island,[15] and received the territory of Songkla in the south.[5]

When Chaumont returned to France, Claude de Forbin, who had accompanied Chaumont with the rank of major aboard the Oiseau, was induced to remain in the service of the Siamese king, and accepted, though with much reluctance, the posts of grand admiral, general of all the king's armies and governor of Bangkok. His position, however, was soon made untenable by the jealousy and intrigues of the minister Phaulcon, and at the end of two years he left Siam, reaching France in 1688. He was replaced as Governor of Bangkok by the Chevalier de Beauregard.[16]

The French engineer Lamarre also remained in Siam at the king's request in order to build fortifications. He began by building a fortress in Bangkok,[17] and designed fortifications for Ligor (Nakhon Sithammarat), Singor (Songkhla), Phatthalung, Ayutthaya, Louvo (Lopburi), Mergui, Inburi and Thale Chupson.[18]

Second Thai embassy to France (1686)

A second Thai embassy, led by Kosa Pan, was sent to France to ratify the treaties. The embassy accompanied the returning embassy of Chevalier de Chaumont and traveled on the boats l'Oiseau and la Maligne. It brought a proposal for an eternal alliance between France and Siam and stayed in France from June 1686 to March 1687. Kosa Pan was accompanied by two other Siamese ambassadors, Ok-luang Kanlaya Ratchamaitri and Ok-khun Sisawan Wacha.,[19] and by the Jesuit Father Guy Tachard.

Kosa Pan's embassy was met with a rapturous reception and caused a sensation in the courts and society of Europe. The mission landed at the French port of Brest before continuing its journey to Versailles, constantly surrounded by crowds of curious onlookers.

The "exotic" clothes as well as manners of the envoys (including their kowtowing to Louis XIV during their visit to him on September 1, 1686), together with a special "machine" that was used to carry King Narai's missive to the French monarch caused much comment in French high society. Kosa Pan's great interest in French maps and images was commented upon in a contemporary issue of the Mercure Galant.[20]

The main street of Brest was named Rue de Siam in honour of the embassy.

Siam-England war (1687)

Meanwhile, Siam entered into conflict with England (the Honourable East India Company, led by Josiah Child), officially declaring war in August 1687.[21] The reason was that the Englishman Samuel White, brother of George White and a friend of Phaulkon, had risen to prominence to become the Governor of Mergui in 1684, replacing his compatriot Barnaby.[22] From there he traded under the Siamese flag and engaged in piracy, sometimes attacking ships under English jurisdiction. The English responded by sending warships to the harbour of Mergui, and the Siamese, fearing that the city might be taken and resenting corruption, massacred most of the English residents there.[23] The result was that the English were banned from Siam.[24] In the place of Samuel White, the French Chevalier de Beauregard was nominated Governor of Mergui by the king of Siam in 1687.[16]

Embassy of Loubère-Céberet (1687)

A second French embassy to Siam was sent in March 1687,[25] organized by Colbert, of which Guy Tachard was again part. The embassy consisted of a French expeditionary force of 1,361 soldiers, missionaries, envoys and crews aboard five warships, and was bringing the Siamese embassy of Kosa Pan home.[26] The military wing was led by General Desfarges, and the diplomatic mission by Simon de la Loubère and Claude Céberet du Boullay, a director of the French East India Company. The embassy arrived in Bangkok in October 1687,[27] on board the warships Le Gaillard (52 guns), L'oiseau (46 guns), La Loire (24 guns), La Normande and Le Dromadaire.[28]

The mission included 14 Jesuit scientists sent to Siam by Louis XIV, under the guidance of Father Tachard. The Jesuits (among whom was Pierre d'Espagnac) were given the title of "Royal Mathematician" and were sponsored by the Academy.[16][16]

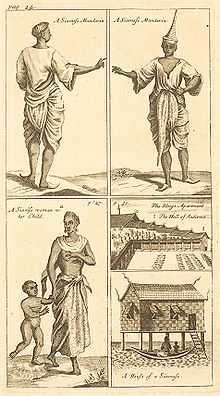

Du Royaume de Siam.

Desfarges had instructions to negotiate the establishment of troops in Mergui and Bangkok rather than the southern Songkla, and to take these locations if necessary by force.[26] King Narai agreed to the proposal, and a fortress was established in each of the two cities, which were commanded by French governors.[29] Desfarges was in command of the fortress of Bangkok, with 200 French officers and men,[30] as well as a Siamese contingent provided by King Narai, and Du Bruant was in command of Mergui with 90 French soldiers.[30][31] In 1688, Jean Rival was named governor of Bangkhli (modern Phang Nga). Another 35 soldiers with 3 or 4 French officers were assigned to ships of the King of Siam, with the mission of fighting piracy.[30]

The diplomatic mission, however, achieved little apart from the reaffirmation of the 1685 commercial treaty. The Jesuit Father Tachard had obtained secret instructions from Seignelay, which allowed him to deal directly with Phaulkon.[32] Hopes for the conversion of King Narai to Catholicism, which had largely motivated the embassy sent by Louis XIV, did not materialize.[32]

As a side-note to the history of mathematics, Simon de la Loubère also brought from his travels to Siam a very simple method for creating n-odd magic squares, known as the "Siamese method" or the "de la Loubère method",[33][34][35] which apparently was initially discovered in Surat, India by another Frenchman by the name of M. Vincent, who was sailing on the return ship with de la Loubère.[36]

Third Thai embassy to France (1688)

Meanwhile the Jesuit Guy Tachard returned to France with the title of "Ambassador Extraordinary for the King of Siam", accompanied by Ok-khun Chamnan, and visited the Vatican in January 1688. He and his Siamese embassy met with Pope Innocent XI and translated Narai's letter to him. In February 1689, the embassy was granted an audience with Louis XIV, and the treaty of commerce Céberet had obtained in 1687 was ratified.[37] Two weeks later a military treaty was signed, designating François d'Alesso, Marquis d'Eragny, as captain of the palace guard in Ayutthaya and inspector of the French troops in Siam.[38]

1688 revolution

The disambarkment of French troops in Bangkok and Mergui led to strong nationalistic movements in Siam directed by the Mandarin and Commander of the Elephant Corps, Phra Petratcha. In April 1688, Phaulkon requested military help from the French in order to neutralize the plot. Desfarges responded by leading 80 troops and 10 officers out of Bangkok to the Palace in Lopburi,[39] but he stopped on the way in Ayutthaya and finally abandoned his plan and retreated to Bangkok for fear of being attacked by Siamese rebels and deterred by false rumors that the king had already died.[40] Desfarges could have eliminated the conspiracy at this point if he had pursued his mission towards Lopburi, and that his judgement failed him, partly based on the false rumours spread by Véret, the Director of the French East India Company in Ayutthaya.[40]

On May 10, the dying King Narai named a regent in the person of his daughter Yothathep. He then learnt that Phetracha was preparing a coup d'état against him.[42] This spurred Phetracha to execute the long-planned coup immediately, initiating the 1688 Siamese revolution.[43] On May 18-17, 1688, King Narai was arrested, and on June 5 Phaulkon was executed. Six French officers were captured in Lopburi and mobbed, one of them dying as a result.[44] Many members of Narai's family were assassinated (the king's brothers, his successors by right, were killed on July 9),[45] and King Narai himself died in detention on July 10–11. Phra Phetracha was crowned king on August 1.[43] Kosa Pan, the 1686 former ambassador to France, as he was one of the most loyalty to King Narai, he became the Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade.[46]

Large-scale attacks were launched on the two French fortresses in Siam, and on June 24, the French under du Bruant soon had to abandon their garrison at Mergui.[43] Du Bruant and the Chevalier de Beauregard managed to escape under fire and with many casualties by seizing a Siamese warship, the Mergui.[31] Du Bruant and his troops were stranded on a deserted island for four months before being captured by a British warship. They ultimately returned to Pondicherry by way of Madras.

Siege of Bangkok

Phetracha besieged the French fortress in Bangkok with 40,000 men,[48] and over a hundred cannon,[49] during a period of four months.[50] The Siamese troops apparently received Dutch support in their fight against the French.[49] On September 9, the French warship Oriflamme, carrying 200 troops and commanded by de l'Estrilles, arrived at the mouth of the Chao Phraya River, but was unable to dock at the Bangkok fortress as the entrance to the river was being blocked by the Siamese.[51]

Phaulkon's Catholic Japanese-Portuguese wife Maria Guyomar de Pinha,[52] who had been promised protection by being ennobled a countess of France, took refuge with the French troops in Bangkok, but Desfarges returned her to the Siamese under pressure from Phetracha on October 18.[53] Despite the promises that had been made regarding her safety, she was condemned to perpetual slavery in the kitchens of Phetracha.[54] Desfarges finally negotiated to return with his men to Pondicherry on November 13, on board the Oriflamme and two Siamese ships, the Siam and the Louvo, provided by Phetracha.[43][55]

Some of the French troops remained in Pondicherry to bolster the French presence there, but most left for France on February 16, 1689, on board the French Navy Normande and the French Company Coche, with the engineer Vollant des Verquains and the Jesuit Le Blanc on board. The two ships were captured by the Dutch at The Cape, however, because the War of the Augsburg League had started. After a month in the Cape, the prisoners were sent to Zeeland where they were kept at the prison of Middelburg. They were able to return to France through a general exchange of prisoners.[56]

On April 10, 1689, Desfarges, who had remained in Pondicherry, led an expedition to capture the island of Phuket in an attempt to restore some sort of French control in Siam.[57][58] The occupation of the island led nowhere, and Desfarges returned to Pondicherry in January 1690.[59] Recalled to France, he left 108 troops in Pondicherry to bolster defenses, and left with his remaining troops on the Oriflamme and the Company ships Lonré and Saint-Nicholas on February 21, 1690.[60] Desfarges would die on his way back trying to reach Martinique, and the Oriflamme would later sink on February 27, 1691, with most of the remaining French troops, off the coast of Britanny.[61]

Duquesne-Guiton mission (1690)

The 1688 Siamese embassy was returned to Siam by the six warship fleet of Abraham Duquesne-Guiton (nephew of the famous Abraham Duquesne) in 1690, but because of unfavourable winds the fleet was only able to go as far as Balassor, at the mouth of the Ganges, where they dropped the embassy.[62] The embassy finally returned to Ayutthaya overland.

Father Tachard (1699)

In 1699, Father Guy Tachard again went to Siam, and managed to enter the country. He met with Kosa Pan, now Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade, and the new king Phetracha, but the meeting remained purely formal and led to nothing.[59] He apparently kept insisting on the establishment of a French fort in Tenasserim, with the effect that negotiations were broken off without any result.[5]

18th century relations

The revolution in Thailand essentially interrupted relations between France and Thailand until the 19th century, although French Jesuits were allowed to continue preaching in Thailand.[5]

After the reestablishment of peace in 1690, Bishop Laneau was able to resume his missionary work until his death in 1696. He was then succeeded by Bishop Louis of Cice (1700–27). The rest of the century consisted in persecutions by the Siamese themselves or by the Burmese invaders. The king kept his favour for Bishops Texier de Kerlay and de Lolière-Puycontat (1755).

Between 1760 and 1765, a French group of gunners under the leadership of Chevalier Milard participated to the Burmese invasions of Siam, as an elite corps of the Burmese army.[63][64]

After the Burmese invasions, in 1769 Father Corre resumed missionary work in Siam, followed by Mgr Lebon (1772–80). Mgr Lebon had to leave in 1775 after persecutions, but his successors Bishops Condé and Garnault returned to Siam.[4]

19th century relations

New missionaries arrived to Siam in 1826 and 1830 (among them Fathers Bouchot, Barbe, Bruguière, Vachal, Grandjean, Pallegoix and Courvezy). In 1834, Mgr Courzevy became Vicar Apostolic of Siam, heralding a new beginning for missionary work. He was succeeded by Bishop Pallegoix (1840–62), who was instrumental in getting Napoleon III to renew the French alliance with Siam.[4]

Some overtures were made by Thailand to establish trade relations with France in 1840 and 1851. Napoleon III sent an embassy to King Mongkut led by Charles de Montigny in 1856. A Treaty was signed on August 15, 1856, to facilitate trade, guarantee religious freedom, and allow the access of French warships to Bangkok. In June 1861, French warships would bring a Thai embassy to France, led by Phya Sripipat (Pae Bunnag).[65]

In the meantime, France was establishing a foothold in neighbouring Vietnam, putting it on a collision course with Siam. Under the orders of Napoleon III, French gunships under Rigault de Genouilly attacked the port of Da Nang in 1858, causing significant damage, and holding the city for a few months. De Genouilly decided to sail south and captured the poorly defended city of Saigon in 1859.[66] From 1859 to 1867, French troops expanded their control over all 6 provinces on the Mekong delta and formed a French Colony known as Cochin China. In 1863, France and the King Norodom of Cambodia signed a treaty of protection with France, which transferred the country from Siamese and Vietnamese overlordship to French colonial rule. A new treaty was signed between France and Siam on July 15, 1867.

Franco-Siamese war (1893)

Territorial conflict in the Indochinese peninsula for the expansion of French Indochina led to the Franco-Siamese War of 1893. In 1893 the French authorities in Indochina used border disputes, such as the Grosgurin affair, followed by the Paknam naval incident, to provoke a crisis. French gunboats appeared at Bangkok, and demanded the cession of Lao territories east of the Mekong. King Chulalongkorn appealed to the British, but the British minister told the King to settle on whatever terms he could get, and he had no choice but to comply. Britain's only gesture was an agreement with France guaranteeing the integrity of the rest of Siam. In exchange, Siam had to give up its claim to the Tai-speaking Shan region of north-eastern Burma to the British, and cede Laos to France. (Although it is to note that the Lao king asked for French protection in place of Siamese rule.)

20th century relations

The French, however, continued to pressure Siam, and in 1906–1907 they manufactured another crisis. This time Siam had to concede French control of territory on the west bank of the Mekong opposite Luang Prabang and around Champasak in southern Laos, as well as western Cambodia. France also occupied the western part of Chantaburi. In the Franco-Siamese Convention signed February 13, 1904,[67] in order to get back Chantaburi Siam had to give Trat to French Indochina. Trat became part of Thailand again on March 23, 1906 in exchange for many areas east of the Mekong river like Battambang, Siam Nakhon and Sisophon.

The British interceded to prevent more French expansion against Siam, but their price, in 1909 was the acceptance of British sovereignty over of Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis and Terengganu under Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909. All of these "lost territories" were on the fringes of the Siamese sphere of influence and had never been securely under their control, but being compelled to abandon all claim to them was a substantial humiliation to both king and country. In the early 20th century these crises were adopted by the increasingly nationalist government as symbols of the need for the country to assert itself against the West and its neighbours.

French-Thai War (1940-1941)

Shortly before World War II, the French government agreed to border negotiations with Thailand which were expected to make minor changes in Thailand's favour. However, France soon fell to Hitler's forces, and the negotiations never took place. Thailand then took the opportunity of French weaknesses to reclaim previously lost territories in French Indo-China, resulting in the French-Thai War between October 1940 and 9 May 1941. Thai military forces did well on the ground and in the air to defeat the French and regain her territory, but Thai objectives in the war were limited. In January, however, Vichy French naval forces decisively defeated Thai naval forces in the Battle of Koh Chang. The war ended in May with the help of the Japanese, allied with Nazi Germany, who coerced the French to relinquish their hold on the disputed border territories.

To commemorate the victory Thailand had the Victory Monument built. Thailand invited Japan and Germany to join the celebration. Japan ordered Shōjirō Iida to join the celebration and The German Foreign Ministry ordered Robert Eyssen to join the celebration.

After the war, in October 1946, northwestern Cambodia and the two Lao enclaves on the Thai side of the Mekong River were returned to French sovereignty after the French provisional government threatened to veto Thailand's membership in the United Nations.[18]

See also

- France–Asia relations

- France-Burma relations

- Sip Song Chau Tai

Notes

- ↑ The Catholic encyclopedia, p.766

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Missions, p.4

- ↑ Les Missions Etrangeres, p.45

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Catholic Encyclopedia

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- ↑ The Cambridge History of Christianity by Stewart J. Brown, Timothy Tackett, p.464

- ↑ History and evolution of western medicine in Thailand Somrat Charuluxananana, Vilai Chentanez, Asian Biomedicine Vol. 1 No. 1 June 2007, p.98

- ↑ Smithies 2002, p.8

- ↑ Les Missions Etrangeres, p.122

- ↑ Smithies 2002, p.9

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Smithies 2002, p.182

- ↑ New Terrains in Southeast Asian History, p.294, Abu Talib

- ↑ Asia in the Making of Europe By Donald F. Lach, p.253

- ↑ Eastern Magnificence and European Ingenuity: Clocks of Late Imperial China - Page 182 by Catherine Pagani (2001)

- ↑ Smithies 2002, p.50, note 99

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 English intercourse with Siam in the seventeenth century - Page 365 by John Anderson - 2000

- ↑ Smithies 2002, p.25, note 21

- ↑ Smithies 2002, p.87

- ↑ Smithies 1999, p.59

- ↑ Suarez, p.29

- ↑ A history of South-east Asia: 2. Ed Page 349 by Daniel George Edward Hall 1964

- ↑ Søren Mentz p.226

- ↑ The English Gentleman Merchant at Work: Madras and the City of London 1660-1740 by Søren Mentz p.227

- ↑ Søren Mentz p.228

- ↑ Mission Made Impossible: The Second French Embassy to Siam, 1687, by Michael Smithies, Claude Céberet, Guy Tachard, Simon de La Loubère (2002) Silkworm Books, Thailand ISBN 974-7551-61-6

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Smithies 2002, p.10

- ↑ Smithies 2002, p.183

- ↑ Narrative of a Residence at the Capital of the Kingdom of Siam by Frederick Arthur Neale, Page 214

- ↑ Smithies 2002, p.99, note 5

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Desfarges, in Smithies 2002, p.25

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 De la Touche, in Smithies 2002, p.76

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Smithies 2002, p.11

- ↑ Mathematical Circles Squared" By Phillip E. Johnson, Howard Whitley Eves, p.22

- ↑ CRC Concise Encyclopedia of Mathematics by Eric W. Weisstein, Page 1839

- ↑ The Zen of Magic Squares, Circles, and Stars by Clifford A. Pickover Page 38

- ↑ A new historical relation, Tome II, p.228

- ↑ Smithies 1999, p.7

- ↑ Smithies 1999, p.8

- ↑ Smithies 2002, p.110

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Smithies 2002, p.18

- ↑ Smithies 2002, p.80

- ↑ Smithies 2002, p.31

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 Smithies 2002, p.184

- ↑ Desfarges, in Smithies 2002, p.39-40

- ↑ Smithies 2002, p.46

- ↑ Desfarges, in Smithies 2002, p.35

- ↑ Smithies 2002, p.95-96

- ↑ Smithies 2002, p.66

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 De la Touche, in Smithies 2002, p.70

- ↑ Smithies 2002, p.71

- ↑ Smithies 2002, p.49, note 93

- ↑ Vollant de Verquains, in Smithies 2002, p.100

- ↑ Smithies 2002, p.11/p.184

- ↑ Desfarges, in Smithies 2002, p.51

- ↑ De la Touche, in Smithies 2002, p.73

- ↑ Smithies 2002, p.19

- ↑ A History of South-east Asia p. 350, by Daniel George Edward Hall (1964) St. Martin's Press

- ↑ Dhiravat na Pombejra in Reid, p.267

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Smithies 2002, p.185

- ↑ Smithies 2002, p.179

- ↑ Smithies 2002, p.16/p.185

- ↑ Smithies 1999, p.9

- ↑ Findlay, Ronald and O'Rourke, Kevin H. (2007) Power and Plenty: Trade, War, and the World Economy in the Second Millennium p.277

- ↑ History of Burma By Harvey G. E. p.231

- ↑ Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- ↑ Tucker, p.29

- ↑ Franco-British Rivalry over Siam, 1896-1904

References

- Colvin, Ian D. (2005) The Cape of Adventure: Strange and Notable Discoveries, Perils, Shipwrecks, Kessinger Publishing ISBN 0-7661-9781-6

- Gunn, Geoffrey C. (2003) First Globalization: The Eurasian Exchange, 1500-1800 Rowman & Littlefield ISBN 0-7425-2662-3

- Hall, Daniel George Edward (1964) A History of South-east Asia St. Martin's Press

- Missions étrangères de Paris. 350 ans au service du Christ 2008 Editeurs Malesherbes Publications, Paris ISBN 978-2-916828-10-7

- Reid, Anthony (Editor), Southeast Asia in the Early Modern Era, Cornell University Press, 1993, ISBN 0-8014-8093-0

- Smithies, Michael (1999), A Siamese embassy lost in Africa 1686, Silkworm Books, Bangkok, ISBN 974-7100-95-9

- Smithies, Michael (2002), Three Military Accounts of the 1688 "Revolution" in Siam, Itineria Asiatica, Orchid Press, Bangkok, ISBN 974-524-005-2

- Lach, Donald F. Asia in the Making of Europe

- Tucker, Spencer C (1999) Vietnam University Press of Kentucky ISBN 0-8131-0966-3

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||