Fréchet space

In functional analysis and related areas of mathematics, Fréchet spaces, named after Maurice Fréchet, are special topological vector spaces. They are generalizations of Banach spaces (normed vector spaces that are complete with respect to the metric induced by the norm). Fréchet spaces are locally convex spaces that are complete with respect to a translation invariant metric. In contrast to Banach spaces, the metric need not arise from a norm.

Even though the topological structure of Fréchet spaces is more complicated than that of Banach spaces due to the lack of a norm, many important results in functional analysis, like the Hahn–Banach theorem, the open mapping theorem, and the Banach–Steinhaus theorem, still hold.

Spaces of infinitely differentiable functions are typical examples of Fréchet spaces.

Definitions

Fréchet spaces can be defined in two equivalent ways: the first employs a translation-invariant metric, the second a countable family of semi-norms.

A topological vector space X is a Fréchet space if and only if it satisfies the following three properties:

- it is locally convex

- its topology can be induced by a translation invariant metric, i.e. a metric d: X × X → R such that d(x, y) = d(x+a, y+a) for all a,x,y in X. This means that a subset U of X is open if and only if for every u in U there exists an ε > 0 such that {v : d(v, u) < ε} is a subset of U.

- it is a complete metric space

Note that there is no natural notion of distance between two points of a Fréchet space: many different translation-invariant metrics may induce the same topology.

The alternative and somewhat more practical definition is the following: a topological vector space X is a Fréchet space if and only if it satisfies the following three properties:

- it is a Hausdorff space

- its topology may be induced by a countable family of semi-norms ||.||k, k = 0,1,2,... This means that a subset U of X is open if and only if for every u in U there exists K≥0 and ε>0 such that {v : ||v - u||k < ε for all k ≤ K} is a subset of U.

- it is complete with respect to the family of semi-norms

A sequence (xn) in X converges to x in the Fréchet space defined by a family of semi-norms if and only if it converges to x with respect to each of the given semi-norms.

Constructing Fréchet spaces

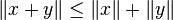

Recall that a seminorm ǁ ⋅ ǁ is a function from a vector space X to the real numbers satisfying three properties. For all x and y in X and all scalars c,

If ǁxǁ = 0 actually implies that x = 0, then ǁ ⋅ ǁ is in fact a norm. However, seminorms are useful in that they enable us to construct Fréchet spaces, as follows:

To construct a Fréchet space, one typically starts with a vector space X and defines a countable family of semi-norms ǁ ⋅ ǁk on X with the following two properties:

- if x ∈ X and ǁxǁk = 0 for all k ≥ 0, then x = 0;

- if (xn) is a sequence in X which is Cauchy with respect to each semi-norm ǁ ⋅ ǁk, then there exists x ∈ X such that (xn) converges to x with respect to each semi-norm ǁ ⋅ ǁk.

Then the topology induced by these seminorms (as explained above) turns X into a Fréchet space; the first property ensures that it is Hausdorff, and the second property ensures that it is complete. A translation-invariant complete metric inducing the same topology on X can then be defined by

Note that the function u → u/(1+u) maps [0, ∞) monotonically to [0, 1), and so the above definition ensures that d(x, y) is "small" if and only if there exists K "large" such that ǁx - yǁk is "small" for k = 0, …, K.

Examples

- Every Banach space is a Fréchet space, as the norm induces a translation invariant metric and the space is complete with respect to this metric.

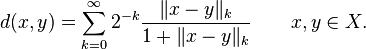

- The vector space C∞([0, 1]) of all infinitely differentiable functions ƒ: [0,1] → R becomes a Fréchet space with the seminorms

- for every non-negative integer k. Here, ƒ(k) denotes the k-th derivative of ƒ, and ƒ(0) = ƒ.

- In this Fréchet space, a sequence (ƒn) of functions converges towards the element ƒ of C∞([0, 1]) if and only if for every non-negative integer k, the sequence (

) converges uniformly towards ƒ(k).

) converges uniformly towards ƒ(k).

- The vector space C∞(R) of all infinitely often differentiable functions ƒ: R → R becomes a Fréchet space with the seminorms

- for all integers k, n ≥ 0.

- The vector space Cm(R) of all m-times continuously differentiable functions ƒ: R → R becomes a Fréchet space with the seminorms

- for all integers n ≥ 0 and k=0, ...,m.

- Let H be the space of entire (everywhere holomorphic) functions on the complex plane. Then the family of seminorms

- makes H into a Fréchet space.

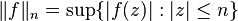

- Let H be the space of entire (everywhere holomorphic) functions of exponential type τ. Then the family of seminorms

- makes H into a Fréchet space.

- If M is a compact C∞-manifold and B is a Banach space, then the set C∞(M, B) of all infinitely-often differentiable functions ƒ: M → B can be turned into a Fréchet space by using as seminorms the suprema of the norms of all partial derivatives. If M is a (not necessarily compact) C∞-manifold which admits a countable sequence Kn of compact subsets, so that every compact subset of M is contained in at least one Kn, then the spaces Cm(M, B) and C∞(M, B) are also Fréchet space in a natural manner.

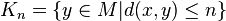

- In fact, every smooth finite-dimensional manifold M can be made into such a nested union of compact subsets. Equip it with a Riemannian metric g which induces a metric d(x, y), choose x in M, and let

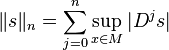

- Let M be a compact C∞-manifold and V a vector bundle over M. Let C∞(M, V) denote the space of smooth sections of V over X. Choose Riemannian metrics and connections, which are guaranteed to exist, on the bundles TX and V. If s is a section, denote its jth covariant derivative by Djs. Then

- (where |⋅| is the norm induced by the Riemannian metric) is a family of seminorms making C∞(M, V) into a Fréchet space.

- The space Rω of all real valued sequences becomes a Fréchet space if we define the k-th semi-norm of a sequence to be the absolute value of the k-th element of the sequence. Convergence in this Fréchet space is equivalent to element-wise convergence.

Not all vector spaces with complete translation-invariant metrics are Fréchet spaces. An example is the space Lp([0, 1]) with p < 1. This space fails to be locally convex. It is a F-space.

Properties and further notions

If a Fréchet space admits a continuous norm, we can take all the seminorms to be norms by adding the continuous norm to each of them. A Banach space, C∞([a,b]), C∞(X, V) with X compact, and H all admit norms, while Rω and C(R) do not.

A closed subspace of a Fréchet space is a Fréchet space. A quotient of a Fréchet space by a closed subspace is a Fréchet space. The direct sum of a finite number of Fréchet spaces is a Fréchet space.

Several important tools of functional analysis which are based on the Baire category theorem remain true in Fréchet spaces; examples are the closed graph theorem and the open mapping theorem.

Differentiation of functions

If X and Y are Fréchet spaces, then the space L(X,Y) consisting of all continuous linear maps from X to Y is not a Fréchet space in any natural manner. This is a major difference between the theory of Banach spaces and that of Fréchet spaces and necessitates a different definition for continuous differentiability of functions defined on Fréchet spaces, the Gâteaux derivative:

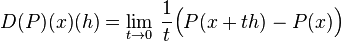

Suppose X and Y are Fréchet spaces, U is an open subset of X, P: U → Y is a function, x ∈ U and h ∈ X. We say that P is differentiable at x in the direction h if the limit

exists. We call P continuously differentiable in U if

is continuous. Since the product of Fréchet spaces is again a Fréchet space, we can then try to differentiate D(P) and define the higher derivatives of P in this fashion.

The derivative operator P : C∞([0,1]) → C∞([0,1]) defined by P(ƒ) = ƒ′ is itself infinitely differentiable. The first derivative is given by

for any two elements ƒ and h in C∞([0,1]). This is a major advantage of the Fréchet space C∞([0,1]) over the Banach space Ck([0,1]) for finite k.

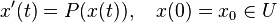

If P : U → Y is a continuously differentiable function, then the differential equation

need not have any solutions, and even if does, the solutions need not be unique. This is in stark contrast to the situation in Banach spaces.

The inverse function theorem is not true in Fréchet spaces; a partial substitute is the Nash–Moser theorem.

Fréchet manifolds and Lie groups

One may define Fréchet manifolds as spaces that "locally look like" Fréchet spaces (just like ordinary manifolds are defined as spaces that locally look like Euclidean space Rn), and one can then extend the concept of Lie group to these manifolds. This is useful because for a given (ordinary) compact C∞ manifold M, the set of all C∞ diffeomorphisms ƒ: M → M forms a generalized Lie group in this sense, and this Lie group captures the symmetries of M. Some of the relations between Lie algebras and Lie groups remain valid in this setting.

Generalizations

If we drop the requirement for the space to be locally convex, we obtain F-spaces: vector spaces with complete translation-invariant metrics.

LF-spaces are countable inductive limits of Fréchet spaces.

References

- Conway, John B. (1990), A Course in Functional Analysis, Graduate Texts in Mathematics 96 (2nd ed.), Springer, ISBN 0-387-97245-5

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Fréchet space", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Rudin, Walter (1991), Functional Analysis, McGraw-Hill Science/Engineering/Math, ISBN 978-0-07-054236-5

- Treves, François (1967), Topological vector spaces, distributions and kernels, Boston, MA: Academic Press

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![\|f\|_k = \sup\{|f^{(k)}(x)|: x \in [0,1]\}](../I/m/346d59475b3d5292bae487a0045fc7d3.png)

![\|f\|_{k, n} = \sup \{ |f^{(k)}(x)| : x \in [-n, n] \}](../I/m/1c10dd123d512a18933ed4226ad0d8b9.png)

![\|f\|_{n} = \sup_{z \in \mathbb{C}} \exp \left[-\left(\tau + \frac{1}{n}\right)|z|\right]|f(z)|](../I/m/f5b19f94ff5edb144cc551f99fe0328d.png)