Fort Conger

| Fort Conger | |

|---|---|

| Ellesmere Island, Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada | |

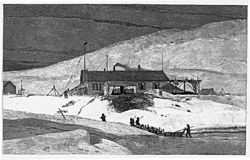

|

Fort Conger, Grinnell Land, May 20, 1883 | |

| Type | Scientific research post |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by |

US Army (originally); Parks Canada (currently) |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1881 |

| In use | Intermittently between 1881 and 1935 |

| Materials |

Wooden boards; tar paper |

| Battles/wars | None |

| Garrison information | |

| Past commanders |

First Lieutenant Adolphus Greely, US Army, Signal Corps |

"Inveniam viam aut faciam ("I shall find a way or make one."), inscribed on a Fort Conger wall by American explorer Robert Peary, 1899.

Fort Conger is a former settlement, military fortification, and scientific research post in Qikiqtaaluk, Nunavut, Canada. It was established in 1881 as an Arctic exploration camp,[3] notable as the site of the first major northern polar region scientific expedition,[4] part of the US government's contribution to the First International Polar Year. In 1991, some of the structures at Fort Conger were designated as Classified Federal Heritage Buildings.[5]

Fort Conger is located on the northern shore of Lady Franklin Bay in northeastern Ellesmere Island within Quttinirpaaq National Park. Bellot Island lies across from Fort Conger within Discovery Harbour. Though lacking in timber, the area is characterized by grasses and sedges. The surroundings are rugged and boast high cliffs around the harbour. Now uninhabited,[6] it is one of only a handful of previously manned stations in the Queen Elizabeth Islands.

History

Before Fort Conger was developed, its Discovery Harbour was used as a wintering site by the crew of the HMS Discovery, led by George Nares, during the British Arctic Expedition of 1875.[7] Though Nares left behind provisions at Fort Conger, most of those supplies were unfound when Fort Conger was established as a research base in 1881 during the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition, led by First Lieutenant Adolphus Greely. The fort was named by Greely after U.S. Senator Omar D. Conger who had supported the expedition. Twenty-five men, including officers, enlisted, and Inuit, lived and conducted research at Fort Conger over the next two years.

During his 1899 expedition to reach the geographic North Pole, Robert Peary reached Fort Conger, only to have several toes snap off at the first joint because of frostbite.[8] Bedridden for weeks while recuperating, Peary wrote on a wall, Inveniam viam aut faciam ("I shall find a way or make one."), attributed to the Roman philosopher Seneca the Elder.[1][2]

Two additional Peary expedition parties returned to Fort Conger in 1905 and 1908. Other explorers used Fort Conger as a base from 1915 through 1935.[5] In 1937, the MacGregor Arctic Expedition attempted to reoccupy Fort Conger.

Construction

The original fort was built as a three-room building, 18 m (59 ft) long, 5 m (16 ft) wide, and 3 m (9.8 ft) high. Lean-tos on either side of the building housed supplies. The double-wall construction of the main building consisted of long, wooden boards, covered with tar paper.[9] This type of construction was found to be unsuitable for the Arctic as it was difficult to keep the building warm.[4]

Peary found Fort Conger to be "grotesque in its utter unfitness and unsuitableness for polar winter quarters" and eventually tore down the original building. Re-using the wood, he built several smaller, adjoining buildings, some of which still stand[4] and are classified as Federal Heritage Buildings.

Research

As a scientific station, Fort Conger has been the site of many research projects from the early "Pendulum Observations",[10] to "Research on the microbes attacking the historic woods at Fort Conger and the Peary huts on Ellesmere Island" conducted by the University of Minnesota.[11] Unexpected large quantities of arsenic have been discovered at Fort Conger in recent years, its presence most likely attributable to it being delivered here for sample preservation.[12] In 2013, a comprehensive 17-page report on the history of Fort Conger was published in the journal, Arctic.[13]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort Conger. |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Fleming, Fergus (2003). Ninety Degrees North: The Quest for the North Pole. Grove Press. p. 308. ISBN 0-8021-4036-X.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Miller, Floyd (2007). Ahdoolo! the Biography of Matthew A. Henson. Read Books. p. 121. ISBN 1-4067-5062-X.

- ↑ "PEARY IS AT FORT CONGER" (PDF). The New York Times. November 10, 1900. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 George, Jane (August 4, 2000). "Fort Conger: old tales of futility and desperation". Nunatsiaq News. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Quttinirpaaq National Park of Canada". pc.gc.ca. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- ↑ "Lady Franklin Bay". The Columbia Gazetteer of North America. bartleby.com. 2000. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ Flemming, Clare. "Collection of the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition 1881-1884". Explorers Club. p. 3. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- ↑ Robinson, Bradley. "Matthew A. Henson (1866-1955)". Arctic (ucalgary.ca) 36 (1): 106–107. doi:10.14430/arctic2253.

- ↑ Mitchell, William (2007). General Greely - The Story of a Great American Author. Read Books. p. 70. ISBN 1-4067-0765-1.

- ↑ Peirce, Charles S.; Max H. Fisch (1986). Writings: a chronological edition. 1872 - 1878 3. Indiana University Press. p. 216. ISBN 0-253-37201-1.

- ↑ "Research on the microbes attacking the historic woods at Fort Conger and the Peary huts on Ellesmere Island". umn.edu. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- ↑ Cullen, William R. (2008). Is arsenic an aphrodisiac?: the sociochemistry of an element. Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 87. ISBN 0-85404-363-2.

- ↑ Bertulli, Margaret M., Lyle Dick, Peter C. Dawson, Panik Lynn Cousins (2013). Fort Conger: a site of arctic history in the 21st century. volume 66, (number 3, September 2013 issue,). Arctic, the journal of the Arctic Institute of North America. p. pages 312–328.