Folk theorem (game theory)

| Folk theorem | |

|---|---|

| A solution concept in game theory | |

| Relationships | |

| Subset of | Minimax, Nash Equilibrium |

| Significance | |

| Proposed by | various, notably Ariel Rubinstein |

| Used for | Infinitely repeated games |

| Example | Repeated prisoner's dilemma |

In game theory, folk theorems are a class of theorems about possible Nash equilibrium payoff profiles in an infinitely repeated game (Friedman 1971).

For an infinitely repeated game, any Nash equilibrium payoff must weakly dominate the minmax payoff profile of the constituent stage game. This is because a player achieving less than his minmax payoff always has incentive to deviate by simply playing his minmax strategy at every history. The folk theorem is a partial converse of this: A payoff profile is said to be feasible if it lies in the convex hull of the set of possible payoff profiles of the stage game. The folk theorem states that any feasible payoff profile that strictly dominates the minmax profile can be realized as a Nash equilibrium payoff profile, with sufficiently large discount factor.

For example, in the Prisoner's Dilemma, both players cooperating is not a Nash equilibrium. The only Nash equilibrium is given by both players defecting, which is also a mutual minmax profile. The folk theorem says that, in the infinitely repeated version of the game, provided players are sufficiently patient, there is a Nash equilibrium such that both players cooperate on the equilibrium path.

In mathematics, the term folk theorem refers generally to any theorem that is believed and discussed, but has not been published. In order that the name of the theorem be more descriptive, Roger Myerson has recommended the phrase general feasibility theorem in the place of folk theorem for describing theorems which are of this class.[1]

Sketch of proof

The proof of the non-perfect folk theorem employs what is called a grim trigger strategy (Rubinstein 1979). All players start by playing the prescribed action and continue to do so until someone deviates. If player i deviates, all players switch to the strategy which minmaxes player i forever after. For players discounting at a high rate, the potential one-stage gain from deviation will not be enough to cover the loss from punishment. Thus all players stay on the intended path.

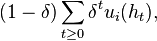

In more detail, assume that the payoff of a player in an infinitely repeated game is given by the average discounted criterion with discount factor 0<δ<1: if a strategy profile results in the path of histories {ht}, player i's payoff is

where ui is player i's utility in the constituent stage game G. The discount factor indicates how patient the players are.

Let a be a pure strategy profile with payoff profile v which strictly dominates the minmax payoff profile. One can define a Nash equilibrium with v as resulting payoff profile as follows:

- 1. All players start by playing a and continue to play a if no deviation occurs.

- 2. If any one player, say player i, deviated, play the strategy profile m which minmaxes i forever after.

- 3. Ignore multilateral deviations.

If player i gets ε more than his minmax payoff each stage by following 1, then the potential loss from punishment is

If δ is close to 1, this outweighs any finite one-stage gain, making the strategy a Nash equilibrium.

The above Nash equilibrium need not be subgame perfect. The threat of punishment may not be credible. Under the additional assumption that the set of feasible payoff profiles is full dimensional and the minmax profile lies in its interior, the argument can be strengthened to achieve subgame perfection as follows.

- 1. All players start by playing a and continue to play a if no deviation occurs.

- 2. If any one player, say player i, deviated, play the strategy profile m which minmaxes i for N periods. (Choose N and δ large enough so that no player has incentive to deviate from phase 1.)

- 3. If no players deviated from phase 2, all player j ≠ i gets rewarded ε above j's minmax forever after, while player i continues receiving his minmax. (Full-dimensionality and the interior assumption is needed here.)

- 4. If player j deviated from phase 2, all players restart phase 2 with j as target.

- 5. Ignore multilateral deviations.

Player j ≠ i now has no incentive to deviate from the punishment phase 2. This proves the subgame perfect folk theorem.

Applications

It is possible to apply this class of theorems to a diverse number of fields. An application in anthropology, for example, would be that in a community where all behavior is well known, and where members of the community know that they will continue to have to deal with each other, then any pattern of behavior (traditions, taboos, etc.) may be sustained by social norms so long as the individuals of the community are better off remaining in the community than they would be leaving the community (the minimax condition).

On the other hand, MIT economist Franklin Fisher has noted that the folk theorem is not a positive theory.[2] In considering, for instance, oligopoly behavior, the folk theorem does not tell the economist what firms will do, but rather that cost and demand functions are not sufficient for a general theory of oligopoly, and the economists must include the context within which oligopolies operate in their theory.[2]

In 2007, Borgs et al. proved that, despite the folk theorem, in the general case computing the Nash equilibria for repeated games is not easier than computing the Nash equilibria for one-shot finite games, a problem which lies in the PPAD complexity class.[3]

Notes

- ↑ Myerson, Roger B. Game Theory, Analysis of conflict, Cambridge, Harvard University Press (1991)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Fisher, Franklin M. Games Economists Play: A Noncooperative View The RAND Journal of Economics, Vol. 20, No. 1. (Spring, 1989), pp. 113–124, this particular discussion is on page 118

- ↑ Christian Borgs, Jennifer Chayes, Nicole Immorlica, Adam Tauman Kalai, Vahab Mirrokni, and Christos Papadimitriou (2007). "The Myth of the Folk Theorem" (PDF).

References

- Friedman, J. (1971), "A non-cooperative equilibrium for supergames", Review of Economic Studies 38 (1): 1–12, doi:10.2307/2296617, JSTOR 2296617.

- Rubinstein, Ariel (1979), "Equilibrium in Supergames with the Overtaking Criterion", Journal of Economic Theory 21: 1–9, doi:10.1016/0022-0531(79)90002-4

- Mas-Colell, A., Whinston, M and Green, J. (1995) Micreoconomic Theory, Oxford University Press, New York (readable; suitable for advanced undergraduates.)

- Tirole, J. (1988) The Theory of Industrial Organization, MIT Press, Cambridge MA (An organized introduction to industrial organization)

- Ratliff, J. (1996). A Folk Theorem Sampler. A set of introductory notes to the Folk Theorem.