Flying Hawk

| Flying Hawk Čhetáŋ Kiŋyáŋ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chief Flying Hawk, Čhetáŋ Kiŋyáŋ. | |

| Oglala Lakota leader | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 1854 |

| Died | December 24, 1931 (aged 77) Pine Ridge, South Dakota |

| Spouse(s) | White Day Goes Out Looking |

| Relations | Kicking Bear (brother) Black Fox II (half brother) Crazy Horse (first cousin)) Sitting Bull (uncle) |

| Children | Felix Flying Hawk (son) |

| Parents | Black Fox (father) Iron Cedar Woman (mother) |

| Religion | Lakota |

Flying Hawk (Oglala Lakota: Čhetáŋ Kiŋyáŋ in Standard Lakota Orthography; a/k/a Moses Flying Hawk; March 1854 – December 24, 1931) was an Oglala Lakota warrior, historian, educator and philosopher. Flying Hawk's life chronicles the history of the Oglala Lakota people through the 19th and early 20th centuries, as he fought to deflect the worst effects of white rule; educate his people and preserve sacred Oglala Lakota land and heritage. Chief Flying Hawk was a combatant in Red Cloud's War and in nearly all of the fights with the U.S. Army during the Great Sioux War of 1876. He fought alongside with his first cousin Crazy Horse and his brothers Kicking Bear and Black Fox II in the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876, and was present at the death of Crazy Horse in 1877 and the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890. Chief Flying Hawk was one of the five warrior cousins who sacrificed blood and flesh for Crazy Horse at the Last Sun Dance of 1877. Chief Flying Hawk is notable in American history for his commentaries and classic accounts of the Battle of the Little Big Horn, Crazy Horse and the Wounded Knee Massacre, and of Native American warriors and statesmen from who fought to protect their families, defend the invasion of their lands and preserve their culture. Chief Flying Hawk was probably the longest standing Wild Wester, traveling for over 30 years throughout the United States and Europe from about 1898 to about 1930. Chief Flying Hawk was an educator and believed public education was essential to preserve Lakota culture. He frequently visited public schools for presentations. Chief Flying Hawk leaves a legacy of Native American philosophy and his winter count covers nearly 150 years of Lakota history.

Early life

Family

Flying Hawk was born about full moon of March 1854, a few miles south of Rapid Creek, Lakota Territory.[1] His father was Oglala Lakota Chief Black Fox, also known as Chief Black Fox I, Cut Forehead and Great Kicking Bear. Chief Black Fox (c.1800-c.1880) had two wives who were sisters who bore him thirteen children. Iron Cedar Woman, the youngest sister, was Flying Hawk's mother and had five children. The other wife had eight children. “In a fight with the Crows, Chief Black Fox was shot below the right eye with an arrow. It was so deep that it could not be pulled out, but had to be pushed through the ear.” Chief Black Hawk died when he was eighty years old. “When my father was dead a long time we went to see how he was on the scaffold where we put him. His bones were all that was left. The arrow-point was sticking in the back of his skull. It was rusted. We took it home with us.” [2] Kicking Bear (c.1846-c.1880) was Flying Hawk's full and older brother. Kicking Bear was a noted warrior and leader of the Ghost Dance. Black Fox II ("Young Black Fox") was Flying Hawk's half-brother and named for his father.[3] Crazy Horse was the first cousin of Flying Hawk. “Though nine years the senior of Flying Hawk, Crazy Horse and Flying Hawk were constant close friends and associates, and they were cousins.” [4] Rattling Blanket Woman, the mother of Crazy Horse, was the sister of Iron Cedar Woman, the mother of Flying Hawk and Kicking Bear. They would have addressed Crazy Horse as ciye, or 'elder brother'.[5] Sitting Bull was Flying Hawk's uncle, Chief Flying Hawk’s mother Iron Cedar Woman and Sitting Bull’s wife being sisters.[6] At the age of 26, Flying Hawk married two sisters, Goes Out Looking and White Day. Goes Out Looking bore him one son, Felix Flying Hawk. White Day had no child.[7]

Intertribal warfare

Flying Hawk was a youth when the white invasion of the Sioux country took place after the American Civil War, flowing into the Great Plains and the mountains of Montana. Flying Hawk wished to be a Chief like his father Black Fox and brother Kicking Bear. To become Chief a warrior must do brave deeds and take many scalps and horses.[8] As a youth, Flying Hawk led many war parties with his older brother Kicking Bear against the Crows and the Piegan.

"When ten years old, I was in my first battle on the Tongue River. It was an overland train of covered wagons who had soldiers with them. The way it was started, the soldiers fired on the Indians, our tribe, only a few of us. We went to our friends and told them we had been fired on by the soldiers, and they surrounded the train and we had a fight with them. I do not know how many we killed of the soldiers, but they killed four of us. After that we had a good many battles, but I did not take any scalps for a good while. I cannot tell how many I killed when a young man."[9]

"When I was twenty years old, we went to the Crows and stole a lot of horses. The Crows discovered us and followed us all night. When daylight came we saw them behind us. I was the leader. We turned back to fight the Crows. I killed one and took his scalp and a field glass and a Crow necklace from him. We chased the others back a long way and then caught up with our own men again and went on. It was a very cold winter. There were twenty of us and each had four horses. We got them home all right and it was a good trip that time. We had a scalp dance when we got back.”[10]

“One night the Piegans came and killed one of our people. We trailed them in the snow all night. At dawn we came up to them. One Piegan stopped. We surrounded the one. He was a brave man. I started for him. He raised his gun to shoot when I was twenty feet away. I dropped to the ground and his bullet went over me; then I jumped on him and cut him through below the ribs and scalped him. We tied the scalp to a long pole. The women blackened their faces and we had a big dance over it.” [11]

“I was thirty-two years old when I was made Chief. A Chief has to do many things before he is Chief, so many brave deeds, so many scalps and so many horses.”[12]

Great Sioux War of 1876-1877

The Great Sioux War of 1876-1877 was a series of conflicts involving the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne tribes. Following the influx of gold miners to the Black Hills of South Dakota, war broke out when the native followers of Chiefs Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse left their reservations, apparently to go on the war path and defend the sacred Black Hills. Flying Hawk fought in Red Cloud's War (1866-1868) and in nearly all of the battles with United States troops during the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877.[13] Flying Hawk fought beside his cousin Crazy Horse and his brothers Kicking Bear and Black Fox II in the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876, and was one of the Five Warrior Cousins who sacrificed blood and flesh for Crazy Horse at the Last Sun Dance of 1877. Flying Hawk was present at the death of Crazy Horse in 1877 and the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890.[14]

Last Sun Dance of 1877

Five warrior cousins

The Last Sun Dance of 1877 is significant in Lakota history as the Sun Dance held to honor Crazy Horse one year after the great victory at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, and to offer prayers for him in the trying times ahead. Crazy Horse attended the Sun Dance as the honored guest but did not take part in the dancing.[15] Five warrior cousins sacrificed blood and flesh for Crazy Horse at the Last Sun Dance of 1887. The five warrior cousins were three brothers, Flying Hawk, Kicking Bear and Black Fox II ("Young Black Fox"), all sons of Chief Black Fox, also known as Great Kicking Bear, and two other cousins, Eagle Thunder and Walking Eagle.[16] The five warrior cousins were braves and vigorous battle men of distinction.[17]

Sun Dance of the Five Warrior Cousins

The Sun Dance is a Lakota religious ceremony. “Only a very brave warrior became a candidate for the Sun Dance, for it meant giving his own body in supreme sacrifice. He must endure the greatest physical pain to ensure that his prayers would be answered. These prayers were to prevent tribal famine or the death of a dear one, or that could bring fortitude in facing immense odds in impending battle or help on behalf of a friend deemed more valuable than himself. It was his way of offering all he had, his own body. After being fastened to the Sun Dance pole by long leather thongs that passed through the flesh of his chest, the participant danced for three or four days without food, water or sleep.”[18]

Fast Thunder acted as ceremonial chief and spiritual pectoral incision overseer of the Last Sundance of 1877.[19] “A tall cottonwood Sun Dance pole was set in the center of the dancing area. Bits of flesh, pinches of tobacco and a pipe were placed in the hole before the pole was raised. The pole symbolically became the stem of the pipe, providing the communication with the Great Spirit. A large shade was then constructed around the Sun Dance Pole, its roof made of animal skins. As each family group came in, they brought a buffalo skin, some covered with wooly brown hair and others tanned a dusty gray. Those who had no buffalo robes brought elk, bear, deer or even sewn-together rabbit skins. Nearby were the medicine man’s tipi where the main dancers prayed and meditated, the sweat bath lodge for purification rights with a huge fireplace.”[20] According to Lakota custom, a commemorative marker of five rocks was placed in a wide V-formation at the ceremonial grounds at the foot of Beaver Mountain in northwestern Nebraska, and reverently dedicated to War Chief Crazy Horse. The rocks were also intended as a permanent memorial to the devotion of the five tribes of the Lakota represented at the ceremony and the five warrior cousins who sacrificed their blood and flesh on behalf of Crazy Horse.[21]

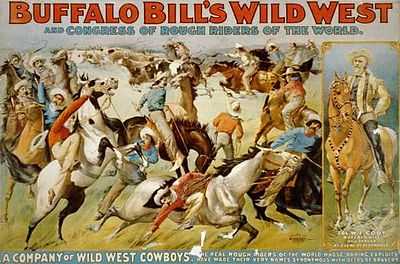

Wild Westing

In the late 1890s, Flying Hawk went Wild Westing with Buffalo Bill Cody. Wild Westing was very popular with the Lakota people and beneficial to their families and communities, and offered a path of opportunity and hope during time when people believed Native Americans were a vanishing race whose only hope for survival was rapid cultural transformation. Between 1887 and World War I, over 1,000 Native Americans went “Wild Westing” with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.[22] Most Wild Westers were Oglala Lakota "Oskate Wicasa" from Pine Ridge, South Dakota, the first Lakota people to go Wild Westing.[23] During a time when the Bureau of Indian Affairs was intent on promoting Native assimilation, Col. Buffalo Bill Cody used his influence with U.S. government officials to secure Native American performers for his Wild West.

Chief Flying Hawk was used to royal receptions in Europe and in America had been entertained by most of the dignitaries of the country.”[24] After Chief Iron Tail’s death on May 28, 1916, Chief Flying Hawk was chosen as successor by all of the braves of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and led the gala processions as the head Chief of the Indians.[25]

“In the spectacular street parades of the great Wild West Shows of old days, Buffalo Bill mounted a beautiful white horse to lead the procession. Alongside of him, mounted on a pinto pony, rode Flying Hawk in full regal style, carrying his feathered guidon erect and fluttering in the breeze, while his eagle-quill bonnet not only made a fitting crown but dangled below the stirrups of his saddle. Scalp locks decorated his buckskin war-shirt, and beaded moccasins adorned his feet, for this was the becoming dress for, and carried out the dignity of his high office of Chief on gala day affairs.”[26]

Only six months after Chief Iron Tail's death, Buffalo Bill died on January 10, 1917. In a ceremony at Buffalo Bill's grave on Lookout Mountain, west of Denver, Colorado, Chief Flying Hawk laid his war staff of eagle feathers on the grave. Each of the veteran Wild Westers placed a Buffalo nickel on the imposing stone as a symbol of the Indian, the buffalo, and the scout, figures since the 1880s that were symbolic of the early history of the American West.[27]

Later, Flying Hawk traveled as a lead performer with Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Show and the Sells Floto Circus. Chief Flying Hawk was probably the longest standing Wild Wester, traveling for over 30 years throughout the United States and Europe from about 1898 to about 1930.

Chief Flying Hawk and Gertrude Käsebier

Gertrude Käsebier was one of the most influential American photographers of the early 20th century and best known for her evocative images of Native Americans. Käsebier spent her childhood on the Great Plains living near and playing with Sioux children. In 1898, Käsebier watched Buffalo Bill’s Wild West troupe parade past her Fifth Avenue studio in New York City, toward Madison Square Garden. Her memories of affection and respect for the Lakota people inspired her to send a letter to Buffalo Bill requesting permission to photograph Sioux traveling with the show in her studio. Cody and Käsebier were similar in their abiding respect for Native American culture and maintained friendships with the Sioux. Cody quickly approved Käsebier's request and she began her project on Sunday morning, April 14, 1898. Käsebier’s project was purely artistic and her images were not made for commercial purposes and never used in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West program booklets or promotional posters.[28]

Käsebier took classic photographs of the Sioux while they were relaxed. Chief Flying Hawk was one of Käsebier’s most challenging portrait subjects. Chief Flying Hawk’s glare is the most startling of Käsebier’s portraits. Other Indians were able to relax, smile or do a “noble pose.” Chief Flying Hawk was a combatant in nearly all of the fights with United States troops during the Great Sioux War of 1876. Chief Flying Hawk fought along with his cousin Crazy Horse and his brothers Kicking Bear and Black Fox II in the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876, and was present at the death of Crazy Horse in 1877 and the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890.[29] In 1898, Chief Flying Hawk was new to show business and unable to hide his anger and frustration imitating battle scenes and from the Great Plains Wars with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West to escape the constraints and poverty of the Indian reservation. Soon, Chief Flying Hawk learned to appreciate the benefits of a Show Indian with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Chief Flying Hawk regularly circulated show grounds in full regalia and sold his “cast card” picture postcards for a penny to supplement promote the show and supplement his income. After Chief Iron Tail’s death on May 28, 1916, Chief Flying Hawk was chosen as successor by all of the braves of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and led the gala processions as the head Chief of the Indians.[30]

Grand Reception for Chief Iron Tail and Chief Flying Hawk

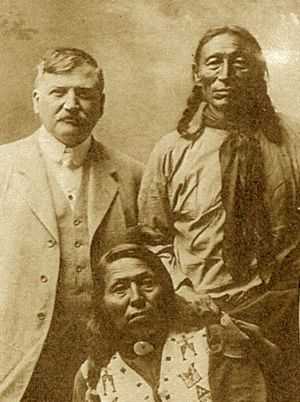

Surprise visits, parties and gala celebrations were common at The Wigwam. In 1915, McCreight hosted a grand reception for Chief Iron Tail and Chief Flying Hawk at The Wigwam. Iron Tail (Oglala Lakota: Sinté Mazá in Standard Lakota Orthography) (1842-May 29, 1916) was one of the most famous Native American celebrities of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and a popular subject for professional photographers who circulated his image across the continents. Iron Tail is notable in American history for his distinctive profile on the Buffalo nickel or Indian Head nickel of 1913 to 1938.

“When Chief Iron Tail was finished with greeting the long line of judges, bankers, lawyers, business men and neighbors who filed past in a receiving line just as the President is obliged to receive and shake the hands of multitude of strangers who call on New Years, the chief grasped hold of the fine buffalo robe which had been thrown over a porch bench for him to rest on drawing it around his shoulders, walked out on the lawn and lay down to gaze into the clouds and over the hundred mile sweep of the hills and valleys forming the Eastern Continental Divide. He had fulfilled his social obligations when he had submitted to an hour of incessant hand-shaking, as he could talk in English, further crowd mixing did not appeal to him. He preferred to relax and smoke his redstone pipe and wait his call to the big dining room. There he re-appeared in the place of honor and partook of the good things in the best of grace and gentlemanly deportment. His courteous behavior, here and at all places and occasions when in company of the writer, was worthy of emulation by the most exalted white man or woman!” After Chief Iron Tail had shaken hands with the assembled guests he gathered the big buffalo hide about his shoulders, waived aside the crowd and walked away. He spread the woolly robe on the grass, sat down upon it and lit his pipe, as if to say, “I’ve done my social duty, now I wish to enjoy myself.”

Chief Flying Hawk long remembered the gala festivities. “Here he and his close friend Iron Tail had held a reception once long ago, for hundreds of their friends, when bankers, preachers, teachers, businessmen, farmers, came from near and far along with their ladies, to pay their respects and say, Hau Cola!” “Flying Hawk recalled that when dinner was served, Iron Tail asked to have his own and Flying Hawk’s meals brought to them on the open porch where they ate from a table he now sat beside, while the many white folks occupied the dining-room, where they could discuss Indians without embarrassment. This, he remembered, was a good time, and they talked about it for a long time together, but now, his good friend had left him and was in the Sand Hills.”

The Wigwam

The Wigwam, Major Israel McCreight’s ("Cante Tanke") home in Du Bois, Pennsylvania, was Chief Flying Hawk’s second home for nearly thirty years. The Wigwam was part of 1,300 acre estate with heavily forested lands and was once the Eastern home of Oglala Lakota "Oskate Wicasa" Wild Westers, and a retreat for Progressive Era politicians, businessmen, journalists and adventurers. Du Bois, a northcentral railroad hub on the Eastern Continental divide, had two active passenger rail stations, and was always a welcome rest stop for weary travelers. For “Old Scouts” Buffalo Bill Cody, Robert Edmund Strahorn and Captain Jack Crawford, from the Great Sioux War, the Wigwam was a place to relax, smoke and talk about the Old West.

Wild Westers needed a place to relax, and The Wigwam was a warm and welcome home where Indians could be Indians, sleep in buffalo skins and tipis, walk in the woods, have a hearty breakfast, smoke their pipes and tell of their stories and deeds. On one occasion 150 Indians with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West camped in the forests of The Wigwam. Oglala Lakota Chiefs Iron Tail and Flying Hawk considered The Wigwam their home in the East. Oglala Lakota Chiefs American Horse, Blue Horse, Jim Grass, Whirlwind Horse, Turkey Legs, Lone Bear, Iron Cloud, Bear Dog, Yellow Boy, Rain-In-The-Face, Hollow Horn Bear, Kills-Close-To-Lodge, Red Eagle, Good Face (Eta Waste), Benjamin Brave (Ohitika) and Thunder Bull visited The Wigwam. Legendary Crow Chief Plenty Coups was also a welcome visitor.

At The Wigwam, Chief Flying Hawk could have rest and relaxation. Show touring schedules were grueling, each spring through fall, with performances twice daily. Traveling, pony riding, war dances and inclement weather weighed on Chief Flying Hawk’s health. Here he could rise with the morning sun for a walk in the forest, enjoy a breakfast of bacon and eggs, with fruit and coffee, smoke his redstone pipe and have a glass of sherry before retiring. Chief Flying Hawk preferred to sleep on the enclosed sun porch at The Wigwam with his robes and blankets and could not be induced to sleep on a white man’s mattress and springs. He refused to be sent to a bedroom, and asked to have the buffalo robes and blankets. With them he made his couch on the open veranda floor, where he retired in the moonlight. McCreight was impressed with Chief Flying Hawk’s grace and dignity: “The Chief was engaged in taking down his long hair-plaits in which were woven strips of otter fur. From his kit sack he took his comb and bottle of bear’s oil and carefully combed and oiled his hair, made up new plaits, then applied a little paint to his cheeks, looked into a small hand-mirror, and was ready to answer questions. His hair, now still reaching to his waist, was streaked with grey. In reply to how Indians were able to retain their hair in such perfect condition, he said they did always retain it, sometimes they got scalped, but they prided themselves in caring for their bodies. He said that long ago Indians often had hair that reached the ground.”

Even in the relaxed atmosphere of The Wigwam, there was a formality to the visits. Of importance, Flying Hawk was an Oglala Lakota Chief and it was his duty to display his beautiful eagle feather “Chief’s Wand” during visits. “At sun-up the Chief was missing. Breakfast was delayed. Presently he was seen coming from the forest which nearly surrounds The Wigwam. In his hand he carried a green switch six feet in length. From his traveling bag he took a bundle which he carefully unfolded and laid out, a beautiful eagle feather streamer which he attached to the pole at either end. After testing it in the breeze he handed it to his friend with gentle admonishment to keep it in a place where it could always been seen. It was the Chief’s “wand,” and he said it must always be kept where it could be seen, else people would not know who was Chief. Having disposed of this, to him, important duty, the Chief was ready for breakfast.”[31]

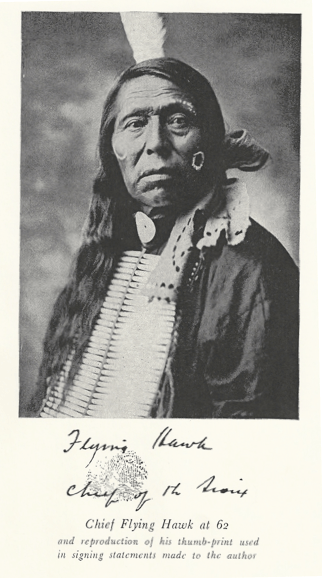

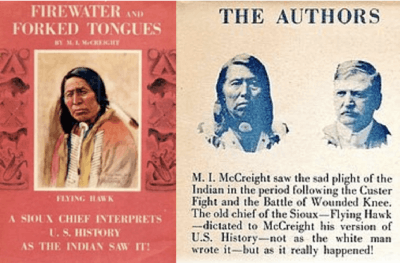

Chief Flying Hawk's Commentaries

After Chief Flying Hawk died in December 1931, McCreight dedicated his life to telling the Old Chief's life. In 1936, at the age of 72, and after eight years of effort, McCreight published Chief Flying Hawk’s Tales: The True Story of Custer’s Last Fight. McCreight followed with 'The Wigwam: Puffs from the Peace Pipe in 1943.[32] In 1947, at the age of 82, McCreight published Firewater and Forked Tongues: A Sioux Chief Interprets U.S. History.[33]

Writing the commentaries

Chief Flying Hawk took the responsibilities of being a chief seriously and always thought about the best way to do things for his people.[34] He appreciated that youth education was essential to preserve Lakota culture and frequently visited public schools for presentations. Flying Hawk wanted to talk about making over the white man’s history so that the young people would know the truth. The white man’s books about Indians did not tell the truth.[35] Major Israel McCreight lived with the Oglala Lakota during the period of their greatest suffering and wanted to tell the story of Native Americans who fought bravely to defend the invasion of their homelands and the lives of their families.[36]

For nearly 30 years, Flying Hawk made periodic visits to The Wigwam, the home of his friend Major Israel McCreight in Du Bois, Pennsylvania. Together, they collaborated to write an Native American’s view of U.S. history. Chief Flying Hawk's commentaries include classic accounts of the Battle of the Little Big Horn, Crazy Horse, the Wounded Knee Massacre, opinions on the European colonization of America, and the statesmen and warriors Red Jacket, Seneca; Little Turtle, Miami; Logan, Oneida; Cornplanter, Seneca; Osceola, Seminole; Red Bird, Winnebago; Pontiac, Ottawa; Tecumseh, Shawnee; Black Hawk, Sauk; Red Cloud, Lakota; and Sitting Bull, Lakota. Chief Flying Hawk was interested in current affairs and an advocate for Native American rights, and requested that his commentaries include a discussion of the status of United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians and the cheating of the Osages in Oklahoma.

On Chief Flying Hawk’s many visits to The Wigwam, these two friends, with the aid of an interpreter, would invariably light up their pipes and begin long discourses on Native American history and current affairs. On each occasion, McCreight would carefully transcribe notes in hope of some day assembling the commentaries for publication. McCreight maintained an extensive library on U.S. history, Indian treaties and reports from government agencies such as the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The library was consulted during the work sessions, and Chief Flying Hawk would often ask that reference materials from the library be translated for him. Through the years, Chief Flying Hawk and McCreight agreed on a formal protocol for recording the commentaries and great care was in assembling the material. First, Chief Flying Hawk would converse with McCreight through one of his two traveling Oglala interpreters, Chief Thunder Bull or Jimmy Pulliam, using a combination of his Lakota language and Indian sign. McCreight was impressed with Chief Flying Hawk’s passionate oration in his native Lakota emphasized by expert sign language to prove his points.[37] “It was thrilling; it was earnest, eloquent and convincing; compelling comparison to the best in the white man’s records.” [38] Next, the information from the discourse was carefully transcribed by McCreight onto paper and read back to the Chief by one of the interpreters for his corrections and approval. Finally, Flying Hawk would sign or mark the pages in ink with his thumbprint, hand them to McCreight, nod his head and declare the paper-talk “Washta” (good).”

September 14, 1928 was a memorable occasion and one of Chief Flying Hawk’s last visits to The Wigwam. The Chief was 76 years of age and extremely ill. He believed that he was nearing the end of his life and wished to review the old notes recorded through the years of visits and add new materials in hope that they would be published. “The Chief said he would soon go to the long sleep and wanted to tell the Indian’s side of things that white people had not told the truth about. The young people had learned to read and should know the truth about history.” [39] The Wigwam was good medicine. The Chief slowly regained his strength, and he was able to finish his final work sessions with the notes and manuscripts before returning to the Black Hills. That month, McCreight completed his first draft of Chief Flying Hawk’s Tales and started searching for publishers. Although McCreight was persistent, the book market at this time was saturated with Wild West stories and the publishing houses showed no interest. Sadly, Flying Hawk and would not live to see his book and passed away on December 24, 1931 at his home in Pine Ridge, South Dakota. Thereafter, McCreight dedicated his life to telling the Old Chief’s story. At the age of 72, and after eight years of effort, McCreight finally published Chief Flying Hawk’s Tales: The True Story of Custer’s Last Fight in 1936.

President Theodore Roosevelt's challenge

McCreight’s second publication of Chief Flying Hawk’s commentaries, Firewater and Forked Tongues: A Sioux Chief Interprets U.S. History was released in 1947 when McCreight was 82 years old. This book contains additional commentary not appearing in Chief Flying Hawk’s Tales.[40] The dedication to Firewater and Forked Tongues quotes President Theodore Roosevelt: “It is greatly to be wished that some competent person would write a full and true history of our national dealings with the Indians. Undoubtedly the latter have suffered a terrible injustice at our hands.” [41] Chief Flying Hawk’s Tales and Firewater and Forked Tongues is a response to President Roosevelt’s challenge. Both men had personal contacts with President Roosevelt. Chief Flying Hawk met every President since President James A. Garfield and liked Theodore Roosevelt the best; McCreight was the father of President Roosevelt’s conservation policy on public and youth education.

Preface to commentaries

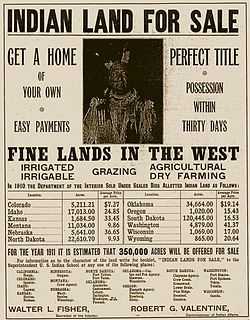

Chief’s Flying Hawk's commentaries reflect a Native American’s views of U.S. history and speak of warriors and statesmen who fought bravely to protect their families, defend the invasion of their lands and safeguard their culture from total destruction. Europeans came to America to escape injustices, and were met by the original proprietors with a handshake and furnished food and shelter. For nearly three centuries, white settlers responded to these benefactors with a relentless campaign of extermination of Native Americans. Treaty upon treaty was broken as American settlement expanded westward to the Pacific. Armed resistance and retaliation by Native American leaders was bloody and fierce, but in the end futile. Eventually, Indian removal became a national policy and the Eastern tribes were forcibly relocated west of the Mississippi River. The Western tribes also fought their wars with the Government. The Sioux Wars were the last efforts of Native Americans to resist the white invasion, ending in the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890. Food was the ultimate weapon in the final conquest, and the power of the Chiefs and the tribes was broken. Tribal lands were annexed and the Indians were confined to reservations on arid lands not suited to agriculture. With the buffalo slaughtered and traditional hunting lands gone, Native Americans became totally dependent on food distribution by the government and churches. In the 19th and 20th century, various policies of the United States federal and state governments attacked Indian cultural identity and attempted to force assimilation. Policies included banning traditional religious ceremonies, mandatory boarding schools for children and restricted freedom of travel and speech.

Chief Flying Hawk as an historian and statesman

Chief Flying Hawk was perhaps the last great Oglala Lakota chief from the Sioux Wars. “No other Indian of his day was better qualified to furnish reliable data covering the great Sioux war, beginning with the ruthless exploitation by rum-runners, prospectors and adventurers, of their homes and hunting grounds forever by sacred treaty with the Government, and ending in the deplorable massacre of Wounded Knee. This old Chief lived through the serious times that befell our people following the gold discovery in the Black Hills.”[42] “He was a youth when the white invasion of Sioux country took place at the close of the Civil War. He was a nephew of Sitting Bull, his mother and Sitting’s Bull’s wife being sisters. His full brother, Kicking Bear, was a leader of the Ghost Dances. He had taken part as a lad in tribal wars with the Crows and the Piegans and he had fought alongside the Great Chief Crazy Horse when Custer was defeated on the Little Big Horn in 1876.”[43] He was a first cousin of Crazy Horse, with whom he participated in nine battles and won them all.[44] Chief Flying Hawk was well qualified as a statesman. Chief Flying Hawk traveled as a lead performer with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West,[45] Miller Brothers 101 Ranch and Sells-Floto Circus for over 30 years throughout the United States and Europe. Chief Flying Hawk was used to extravagant receptions. In Europe he had rounds of them from royalty, and in America had been entertained by most of the dignitaries in the country.[46] Flying Hawk met ten Presidents of the United States and liked Theodore Roosevelt the best for he was a “neighbor in his country.” Harrison, he said, did not treat them right in the uprising of 1890 when they were starving."[47]

Native American history

Chief Flying Hawk commented on a variety of topics including Pre-Columbian civilization; the Spanish conquests of Christopher Columbus, Hernán Cortés and Francisco Vásquez de Coronado; the English colonization of America by Sir Walter Raleigh’s English Expedition of 1584; the Dutch colonization with New Amsterdam and Kieft's War; and massacres of Indians at Sand Creek, Battle of Washita River, The Baker Massacre and Wounded Knee.

Pennsylvania history

During his stays at The Wigwam, Flying Hawk became interested in early Pennsylvania history. He cited William Penn as a man who wished to see fair play, good faith and honesty extended to the Indians. Flying Hawk said if Penn had been obeyed by his officials and followers, there would have been no Indian wars in the Pennsylvania. But when they began to steal Indian land like was done in the Walking Purchase, and cheating them in every trade by getting them drunk, then the Indians retaliated. For half a century the Indians killed white settlers, burned their homes and crops and took their women and children prisoners. The Indians liked the French best because they did not take their land, but only wanted furs. But the English cut down their forests, killed their game and treated them as they did wild animals, wanting only to drive them back so that they could possess their country.[48]

McCreight told Flying Hawk how Indians had killed his great grandfather in 1794. How an Indian had hidden behind a log on the river bank and shot him through the groin while steering a houseboat on the Kiskiminetas River but a few miles from The Wigwam. He asked the Chief how he would explain such a wholly uncalled-for criminal act. Slow to reply, the Chief wanted to ask if this man was a soldier. Told that he had been a captain in the Revolution, the old man said that either the Indian knew the white man, or was drunk when he did the shooting. Investigation of the affair showed that the Indian had been in Pittsburgh and had been drinking that day. But, as the captain shot the Indian, both assailant and victim were dead and nothing was done or could be done about it.[49]

Native American warriors and statesmen

Chief Flying Hawk appreciated that youth education was essential to preserve Lakota culture. During his travels, he frequently visited public schools for presentations, and wanted to talk about making over the white man’s history so that the young people would know the truth. Flying Hawk wanted school history programs to tell the stories of Native American warriors and statesmen who fought to protect their families, defend the invasion of their lands and preserve their culture. He selected Native American warriors and statesmen from different tribes: Red Jacket, Seneca; Little Turtle, Miami; Logan, Oneida; Cornplanter, Seneca; Osceola, Seminole; Red Bird, Winnebago; Pontiac, Ottawa; Tecumseh, Shawnee; Black Hawk, Sauk; Red Cloud, Lakota; and Sitting Bull, Lakota. Flying Hawk was impressed with the oratory of Red Jacket, Logan,[50] Black Hawk,[51] Tecumseh, Sitting Bull and Red Cloud, and requested that their speeches be included in his commentaries.

The Seneca

Chief Flying Hawk once visited some of the survivors of the Seneca tribe in New York State and had great admiration for their great Chiefs Cornplanter and Red Jacket. He wished to put something in his commentaries to show his regard for them. When McCreight informed Flying Hawk that Cornplanter’s father was white and was raised by his Seneca mother, “The Chief said with a smile, That is why he amounted to something.” [52] Flying Hawk requested that Red Jacket’s Speech on "Religion for the White Man and the Red" be included in his commentaries.[53]

Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull was Flying Hawk’s uncle, Flying Hawk’s mother and Sitting Bull’s wife being sisters. He knew him well and wished to talk about him.[54] Flying Hawk observed that Sitting Bull was the key strategist before and again after the fight was over. The fighting was led by Crazy Horse, his young War Chief, and Sitting Bull was not in the Custer fight. “He was a strong speaker just like any white senator. He was a good politician. White politicians are only ‘medicine men’ for their people are most time crazy.”

Flying Hawk was angry about the killing of Sitting Bull.

“The Great Chief would have willingly done anything that James McLaughlin, the agent, or Colonel Cody asked him to do. There was no need to arrest him, he was not doing wrong. He was celebrating the coming of the new Christ who was to restore the buffalo so that his people could once more have peace and plenty, instead of then persecution, hunger, disease and death that confronted them.”

“Sitting Bull was all right but they got afraid of him and killed him. They were afraid of my cousin Crazy Horse, so they killed him. These were the acts of cowards. It was murder. We were starving. We only wanted food.”[55]

“Did you ever know of Indians hanging women as witches? Did you ever hear of Indians burning their neighbors alive because they would not worship a God they did not believe in when priest and parson could not agree? But you know the whites murdered Sitting Bull because he was holding religious ceremonies with the ghost dancers, the same religion that the white man’s priest had taught them to follow!”[56]

Red Cloud

Chief Flying Hawk regarded Red Cloud as "The Red Man’s George Washington." Flying Hawk fought beside Crazy Horse in Red Cloud's War. Chief Red Cloud defeated the U.S. Army in battle, and The Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868) was a great victory. The U.S. Army Powder River Country forts were abandoned and the hunting grounds of the Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho had been protected. Flying Hawk believed that Red Cloud was one of the wisest Native American leaders.

Red Cloud knew what was best for his people and had tried to keep peace with the whites, but it was no use. The whites would not stay out of the Indian’s country, and came and took their gold and killed off all their game. Thus started the trouble and the long bloody war when the soldiers came. After the massacre at Wounded Knee, Red Cloud made a speech. Flying Hawk asked to have the speech read to him, and McCreight brought a volume from the library containing the speech, and it was carefully translated to him by Thunder Bull to refresh his memory. The Chief directed that it be included in his commentaries to tell why they killed Custer and his troopers, and about the Ghost Dance.[57]

Crazy Horse

Recollections of Crazy Horse

“Crazy Horse was a great leader. White men who contended with him and knew him well, spoke of him in the highest terms. His word was not called into question by either white men or red. He was honored by his own people and respected by his enemies. Though they hunted and persecuted him, they murdered him because they could not conquer him.”

“He was born in Southern Dakota Territory in 1844, and his parents gave him the best training as a youth. He grew to manhood, when it was said of him that he was ‘uncommonly handsome, of imposing stature and an Apollo in symmetry, a splendid example of refinement and grace, modest and courteous always, and born leader of men.”[58]

“In his boyhood days there were few white men to be seen, but when met, they extended a hand of friendship. His name derived from a personality like a high-spirited and uncontrolled horse, hence crazy or wild horse. He was an expert horseman. When sixteen years old, he was taken along with a war-party headed by Hump, a famed Sioux Chief, on a campaign against the Gros Ventres. In the fight which came, the Chief’s horse was shot. The enemy rushed in to scalp him while struggling for release from the fallen animal, when Crazy Horse drove his pony alongside and rescued Hump, both escaping on the boy’s horse.”[59]

“When still under twenty, in a winter hunt alone, he brought in ten buffalo tongues for a council feast then being held by old men of the tribe. These were all taken with bow and arrows.”[60]

Crazy Horse spoke this story to Flying Hawk: ‘I was sitting on a hill or rise, and something touched me on the head. I felt for it and found it was a bit of grass. I took it to look at. There was a trail nearby and I followed it. It led to water. I went into the water. There the trail ended and I sat down in the water. I was nearly out of breath. I started to rise out of the water, and when I came out I was born by my mother. When I was born I could know and see and understand for a time, but afterwards went back to it as a baby. Then I grew up naturally. At the age of seven I began to learn, and when twelve began to fight enemies. That was the reason I always refused to wear any war-dress. Only a bit of grass in the hair. That was why I always was successful in battles. The first fight was with the Shoshones. The Shoshones were chasing the Sioux. I, with my younger brother riding double. Two of the Shoshones came for us. We started to meet them. I killed one of them and took his horse. We jumped on him, my brother and I double, and escaped.” [61]

“The young brother of Crazy Horse (Little Hawk) was on a trip where now is Utah, and there he was killed by some white settlers. They were having some trouble with the Indians there. When Crazy Horse learned that his brother was killed he took his wife with him and went away but told no one where he was going. He was gone for a long time. He went to the place where his brother was killed and camped in thew woods where he could see the settlement. He stayed there nine days. Every day he would look around and when he saw someone he would shoot him. He killed enough to satisfy and then he came home.”[62]

“Crazy Horse was never with other Indians unless it was in a fight. He was always the first in a fight, and the soldiers could not beat him in a fight. He won every fight with the whites.” [63]

“Crazy Horse was married but had no children. He was much alone. He never told stories and never took a scalp from his enemies when he killed them. He was the bravest Chief we ever had. He was the leader and the first at the front of the Custer fight. He never talked but always acted first. He was my friend and we went in the Custer fight together.”[64]

“It is well known that he would never take a scalp from his fallen enemy. He struck the body with a switch - coupstick- to show that he neither cared for their weapons, nor cared to waste his. He never dressed in gaudy regalia, feathers and paint a beads; never took part in public demonstrations or dances. He was not an orator and was never known to make a speech. He never sat for a photograph. Yet as a War Chief, he won every battler that he undertook. Once he was attacked in camp when he had his woman and children with them, yet he was able to extricate them with great credit and little loss.” [65]

"I have been in nine battles with Crazy Horse; won them all. Crazy Horse was quiet and not inclined to associate with others; he was in the front of every battle; he was the greatest leader of our tribe.”[66]

“He was a master of strategy.”[67]

“As the youth came to manhood there were rumblings of trouble with the whites, and soon the great Sioux was came on. Spotted Tail, then Chief of the Tetons, and Red Cloud, with other leaders, decided there must be a stand made or they would be annihilated in the grand rush of white hordes who were building roads and railroads into their hunting grounds. At a Grand Council in 1866 it was decided to fight, and when the government built Fort Phil Kearny in the heart of the buffalo range, Crazy Horse took the lead to drive out the invaders. His attack on the Fetterman party at the timber-cutting showed that he was a master of strategy.”[68]

“Thereafter the war became general and Crazy Horse was recognized as a formidable antagonist by the Government’s armies, and the allied tribes acknowledged him as a leader in carrying out the Council’s program of campaigns to fight the troops. For years his band was followed in winter and in summer. The soldiers tracked them as they would trail wild animals to the lair, surrounded and struck them while asleep in their tepees. Every effort was exerted to capture or exterminate Crazy Horse and his people, but without success.” [69]

The Battle of the Little Big Horn

.jpg)

“Baffled on every turn, the Government organized a formidable army of four grand divisions. Crook to advance from the south at Fort Laramie into the Powder River country, Gibbon to come from the west and Custer’s cavalry to join Terry’s division on the Yellowstone, and all to close in on the allied tribes who were believed to be in the game country on the headwaters of the Rosebud and Big Horn Rivers. Crook had reached the head of Rosebud with his army mid-July when contact was made with the Indians. Here Crazy Horse turned on him and gave him such a fight that he turned back and his army never made the junction with Terry, Gibbon and Custer as he set out to do.” [70]

“From here Crazy Horse took his band over the divide to Little Big Horn to get with Sitting Bull’s camp and where they hoped to be let alone. But this was not to be for in the meantime Terry had received Custer’s troops and sent his cavalry division up the Rosebud Valley expecting to find the Indians somewhere near it's head. They crossed to the Little Big Horn and discovered their camps along its west side. The other divisions were not there to help and Custer decided to go it alone. Reno was ordered to open attack on the camp upstream, while Custer himself followed down the east side to attack them where villages were more concentrated. He was not aware that Crazy Horse had stopped his expected aid from Crook a week before and that he was now here and ready to lead his warriors to his own army’s extermination.” [71]

“The Indians were camped along the west side of the Big Horn in a flat valley. We saw a dust but did not know what caused it. Some Indians said it was the soldiers coming. The Chief saw a flag on a pole on a hill. The soldiers made a long line and fired into out tepees among our women and children. That was the first we knew of any trouble. The women got their children by the hand and caught up their babies and ran in every direction.” [72]

“The Indian men got their horses and guns as quick as they could and went after the soldiers. Kicking Bear and Crazy Horse were in the lead. There was the thick timber and when they got out of the timber there was where the first of the fight was.”[73]

“We got right among the soldiers and killed a lot with our bows and arrows and tomahawks. Crazy Horse was ahead of all, and he killed a lot of them with his war-club. He pulled them off their horses when they tried to get across the river where the bank was steep. Kicking Bear was right beside him and killed many too in the water.”[74]

“This fight was in the upper part of the valley where most of the Indians were camped. It was some of the Reno soldiers that came after us there. It was in the day just before dinner when the soldiers attacked us. When we went after them they tried to run into the timber and get over the water where they had left their wagons. The bank was about this high [twelve feet indicated] and steep, and they got off their horses and tried to climb out of the water on their hands and knees, but we killed nearly all of them when they were running through the woods and in the water. The ones that got across the river and up the hill dug holes and stayed in them.”[75]

“Crazy Horse and Flying Hawk were at the upper village when Reno’s troop formed a line after dismounting, and opened fire on the tepees where only women and children were. It was the first intimation that these two Indians had that soldiers were in the vicinity.” [76]

“The Indians could have wiped out Reno’s and all the rest of the soldiers, just as they did Custer’s troops if they had been so disposed. But as Reno had dug in and was willing to quit, the red folks decided to leave them there. They went to look after their women, children and old people who had not been killed in the first assault when no one was with them to defend them and packed up their belongings and left the bloody scene.” [77]

“The soldiers on the hill with the pack-horses began to fire on us. About this time all the Indians had got their horses and guns and bows and arrows and war-clubs and they charged the soldiers in the east and north on top of the hill. Custer was farther north than these soldiers were then. He was going to attack the lower end of the village. We drove nearly all that got away from us down the hill along the ridge where another lot of soldiers were trying to make a stand.” [78]

“Crazy Horse and I left the crowd and rode down along the river. We came to a ravine, then we followed up the gulch to a place in the rear of the soldiers that were making the stand on the hill. Crazy Horse gave his horse to me to hold along with my horse. He crawled up the ravine to see where he could see the soldiers. He shot them as fast as he could load his gun. They fell off their horses as fast as he could shoot.” [Here the Chief swayed rapidly back and forth to show how fast they fell.] When they found they were being killed so fast, the ones that were left broke and ran as fast as their horses could go to some other soldiers that were further along the ridge toward Custer. Here they tried to make another stand and fired some shots, but we rushed them along the ridge where Custer was. Then they made another stand (the third) and rallied a few minutes. Then they went along the ridge and got with Custer’s men.” [79]

“Other Indians came to us after we got most of the men at the ravine. We all kept after them until they got to where Custer was. There was only a few of them left then. By that time all the Indians in the village got their horses and guns and watched Custer. When Custer got nearly to the lower end of the camp. he started to go down a gulch, but the Indians were surrounding him, and he tried to fight. They got off their horses and made a stand but it was no use. Their horses ran down the ravine right into the village. The squaws caught them as fast as they came. One of them was a sorrel with white stocking. Long time after some of our relatives told us that they had seen Custer on that kind of horse when he was on the way to the Big Horn.” [80]

“When we got them surrounded the fight was over in one hour. There was so much dust we could not see much, but the Indians rode around and yelled the war-whoop and shot into the soldiers as fast as they could until they were all dead. One soldier was running away to the east but Crazy Horse saw him and jumped on his pony and went after him. He got him about half a mile from the place where the other soldiers were lying dead. The smoke was lifted so we could see a little. We got off our horses and went and took the rings and money and watches from the soldiers. We took some clothes off too, and all the guns and pistols. We got seven hundred guns and pistols. Then we went back to the women and children and got them together that were not killed or hurt.” [81]

“We did not mutilate the bodies, but just took the valuable things we wanted and left. We got as lot of money but it was of no use.” [82]

“The story that white men told about Custer’s heart being cut out is not true.” [83]

“There was more than one Chief in the fight. But Crazy Horse was leader and did most to win the fight along with Kicking Bear.” [84]

“The names of the Chiefs in the fight were Crazy Horse, Lame Deer, Spotted Eagle and Two Moon. Two Moon led the Cheyennes. Gall and some other Chiefs were there but the ones I told you about were the leaders.[85]

“Sitting Bull was not in the Custer fight, but was one of the main advisors in the strategy before and again after the fight was over.” [86]

“It was hard to hear the women singing the death song for the men killed and for the wailing because their children were shot while they played in the camp. It was a big fight. The soldiers got just what they deserved this time. No good soldiers would shoot into an Indian’s tepee where there were women and children. These soldiers did, and we fought for our women and children. White men would do the same if they were men.” [87]

“We got our things packed up and took care of the wounded the best we could, and left the next day. We could have killed all the men that got into holes on the hill, but they were glad to let us alone, and so we let them alone too. Rain-in-the-Face was with me in the fight. There were twelve hundred of us. Might be no more than one thousand in the fight. Many of our Indians were out on a hunt.” [88]

After the Custer Fight

“Sitting Bull with his people went to Canada to escape the storm of shot and shell which was sure to be rained on them after the story of Custer’s defeat became known in the east. But Crazy Horse stayed on, defiant of his enemies who now more than ever recognized his capabilities for taking care of himself and his persecuted people. Reduced from the scattering of the separate tribes, his people suffered greatly for lack of food in the severe winter which followed and the persistent trailing by guerrilla warfare troops which were furnished with transport, telegraph and the best equipment. He had women and children with him and had to provide food, warm clothing and shelter for them at all times. It was like a pack of hungry wolves on the track of a strayed mother sheep and her lambs!” [89]

“Crazy Horse decided to accede to the plea of the reservation authorities that he come in and accept their promise of supplies and fair treatment. Therefore, in July of 1877 he with several thousands of his own and other Chiefs’ followers, surrendered and came in to the reservation with the distinct condition that the Government would hear band grant his claims.” [90]

“Instead, General Crook immediately recognized Spotted Tail as the head Chief, knowing he had turned against his own people and favored anything the army stood for, and might be depended on to control the late prisoners with military severity. This was received with bitterness by practically all the reservation Indians. Failure to provide food and supplies as promised soon stirred up contention between Spotted Tail adherents and the great number of surrendered people. They of the agency power blamed Crazy Horse. He had been their leader and unconquered enemy of the army forces and might lead them again to liberty from their unsatisfactory position if the surrendered horde at any time so decided. So a conspiracy was formed to assassinate the War Chief. It was discovered by friends of Crazy Horse who told him. He replied by saying ‘only cowards and murderers’ and went about his daily routine.” [91]

“At the time this tale was brought to him, his wife was critically ill and he took her to her parents at Spotted Tail Agency some miles north. During his absence on this mission of love and kindness, his enemies spread the report that he had left to organize another war. Scouts were sent to arrest him. He was overtaken while in the wagon with his sick wife and one other person. He was not arrested but permitted to deliver his patient into the care of her parents.” [92]

“Crazy Horse returned voluntarily, not suspecting any immediate treachery. When he reached the agency, a guard directed him to enter the guard-house. His cousin Touch-the-Cloud, called to him “They are going to put you in the guard-house!” He stopped suddenly to say, “Another white man’s trick, let me go.” But he was held by guards and police, and when he tried to free himself from their grasp, a soldier stepped from behind and ran a bayonet through his kidney. He died during the night while his father sand the death song over his prostrate body. His father and mother and neighbors carried the body to a secret cave, saying it must not be polluted by the touch of any white man.” [93]

“I was present at the death of Crazy Horse; he was my cousin; his father and his two wives and an uncle of Crazy Horse took the body away, and no one knows today were he is buried. Several years later, they went to see how the body was, and when the ground was removed, they found the bones, and they were petrified; they would never tell where they buried him.” [94]

“Crazy Horse was a great leader. White men who contended with him and knew him well, spoke of him in the highest terms. His word was not called into question by either white men or red. He was honored by his own people and respected by his enemies. Though they hunted and persecuted him, they murdered him because they could not conquer him.” [95]

United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians

Chief Flying Hawk was interested in current affairs and was an advocate for Native American rights. The Sioux never accepted the legitimacy of the annexation of the Black Hills “Paha Sapa“. In 1920, lobbyists for the Sioux persuaded Congress to authorize a lawsuit against United States in the U.S. Claims Court to seek redress for grievances. In 1923, Chief Flying Hawk, with the support of McCreight, called upon the Council to file the case of United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians. In a later visit to The Wigwam, McCreight asked Flying Hawk about the status of the case. Flying Hawk appealed to his interpreter to make it clear that the treaty with Napoleon was broken at the time that his country was purchased, and that the whites had, from the beginning of relations with their tribe, ignored and wholly repudiated their first and principle obligation toward the Sioux. [96]

McCreight, who studied the treaties between the Sioux Nation and the United States, served as an expert on Native American affairs and traveled to Washington, D.C. to assist lawyers for the Sioux Nation.[97] Chief Flying Hawk was familiar with the legal claims and pleadings and requested that his commentaries include the swindlings that were perpetrated upon the Sioux tribe in so-called land purchases. Litigation between the Sioux and the government would continue well into the 20th century.[98]

The Osages in Oklahoma

Chief Flying Hawk also requested that a portion of the U.S. Indian Commission’s Annual Report for 1926 citing the cheating of the Osages in Oklahoma be officially included in his commentaries.

“The Chief lit his pipe and relaxed while Jimmy Pulliam (the interpreter) related the old man’s attempt to enlighten him. He was telling Jimmy of the cheating of the Osages in Oklahoma, and that it had been published by the Indian Commission in a recent annual report. This report the host had, and stepping to the library brought it out for Jimmy to read to the Chief. How! How! The Chief said, and demanded that it be written into his statement.”

“The situation in which these Indians find themselves was developed by white men without regard to the interests of the Indians. Nor can we ignore the unhappy fact that for eighteen years or more, these wards of the United States, living in forty counties in Oklahoma, have been shamefully exploited by a group of guardians and their attorneys, whose unconscionable deeds are matters of public record state of affairs and of common knowledge. The land and money stolen from the Indians cannot be given back to them. But it is not too late for Federal and State authorities, legislative and executive, to adopt measures to prevent further civil exploitation of these Indians, and to safeguard their interests and promote their welfare. It is common knowledge that grafting on rich Indians has become an almost recognized profession in Eastern Oklahoma, and a considerable class of unscrupulous individuals find their chief means of livelihood and source of wealth in this grafting. So common is it that the term grafter carried little or no opprobrium in Oklahoma.”

“Long ago the Indians were forced into Indian Territory, because it was land the white man did not then want. Then oil was found, and the white man wanted it very much indeed. But now they could not force the Indian to leave, they had to pay him for the oil. They gave him money for the oil, then cheated him out of the money.” [99]

Three years later, U.S. Commissioner for Indian Affairs Charles H. Burke was asked to resign for the Oklahoma scandal. To McCreight's great surprise, he was nominated for the post in April 1929, by Ray Lyman Wilbur, Secretary of the Department of the Interior.[100] McCreight was considered a national figure in Indian lore and among the two or three men in the United States having the best knowledge of the American Indian and their affairs.[101] McCreight received many endorsements including the National Council of American Indians of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota and the Oglala Lakota representing “eight thousand and 300 Indians.” McCreight was not to receive the appointment and President Herbert Hoover chose Philadelphia financier Charles James Rhoads. McCreight noted: “My education being red school house and hard knocks, did not measure up to Hoover’s class. Rhoads is a fine fellow, Quaker, College-bred and rich. However, I value the endorsement of the Indians more than I would have the endorsement of Mr. Hoover, so there you have it.”

Chief Flying Hawk’s Winter Count

Chief Flying Hawk was a Lakota historian and authored a “winter count” covering nearly 150 years of Lakota history. Lakota years are conceived as extending from the first snow of a winter to the first snow of the next winter. Years are given names based upon significant or unique event that would be easy to recall. For example, Chief Flying Hawk’s Winter Count for 1866 records the Fetterman Fight during Red Cloud’s War as “Wasicu opawinge wica ktepi” or “They killed one hundred white men.” Likewise, 1876 is “Marpiya llute sunkipi” or “They took horses from Red Cloud” (the U.S. Army did after the Battle of the Little Big Horn), 1877 is “Tasunka witko ktepi” or “When they killed Crazy Horse” and 1890 is “Si-tanka ktepi” or “When they killed Big Foot” (the Wounded Knee Massacre). Chief Flying Hawk specifically requested that his Lakota calendar be included the commentaries.[102]

Last visit to The Wigwam

On Sunday, June 23, 1929, Chief Flying Hawk made his last visit to The Wigwam. McCreight sent him clothes since all of his belongings had been lost while performing in Harrisburg. Saturdays and Sundays were always reserved as a day off for the performers. The show was in Oil City, Pennsylvania, the following day. In accordance with established show procedures, a request was made by McCreight for a visit along with transportation arrangements. Chief Flying Hawk was accompanied by his friend and interpreter Chief Thunder Bull.

The Old Chief signed a desire for a smoke and the Red Cloud peace-pipe with its long ornamental stem was brought from the cabinet, and some red-willow bark mixed with tobacco for the old time kinnikinnick, which the Chief enjoyed as between puffs he recalled notable Councils of Treaty with government agents. He said they always talked with “forked tongues” and did not always do as they agreed on paper. “It was Sunday. Flying Hawk's leave of absence was about up and his visit to his white brother was coming to an end. The old man had arisen with the sun and had taken a long walk in the woods to see the squirrels and hear the birds sing, he said. After breakfast, the Chief said that he wanted to go to church. A car was brought around, loaded to capacity, and the old Chief, in full dress and just a little paint on his face to cover his wrinkles, took place beside his host for a trip of two miles to the big Catholic edifice on State Street in the city's First Ward. Throughout the service the Chief responded with dignity to every detail of the long and solemn ceremony--and it may be said too that he attracted the gaze of everyone present. When formal service ended, the popular Father McGivney came to take his hand in welcome and gave his blessing, but it was long before the Chief was permitted to take leave of his friends and neighbors gathered about him to shake hands. The Chief was visibly agitated and frequently referred to his disappointment in having to go. He said he would not likely ever come again; he felt that he would soon go to join his friends in the Sand Hills.”

Chief Flying Hawk's teachings

Flying Hawk leaves a legacy of Native American wisdom and spiritual teachings:[103]

“The white man does not obey the Great Spirit; that is why the Indians never could agree with him.”[104]

“The white people fight among themselves about religion; for this they have killed more than in all other wars; did you ever hear of Indians killing each other about worshiping the Great Spirit?”[105]

“Does the white man know who is right if the Indian says his great grandfather was a bear, and the white man says his great grandfather was a monkey?”[106]

"The tepee is much better to live in; always clean, warm in winter, cool in summer, easy to move. The white man builds big house, cost much money, like big cage, shut out sun, can never move; always sick. Indians and animals know better how to live than white man; nobody can be in good health if he does not have all the time fresh air, sunshine and good water. If the Great Spirit wanted men to stay in one place he would make the world stand still; but he made it to always change, so bird and animals can move and always have green grass and ripe berries, sunlight to work and play, and night to sleep; summer for flowers to bloom, and winter for them to sleep; always changing; everything for good; nothing for nothing.”[107]

“The white people will soon be gone, they go so fast they do not take time to live, but they will learn maybe before they all die. Now they are taking a lesson from the Indian; they make their wigwam on wheels and go on the trail like red people do; Indians make travois and pony pull their tepee; white man’s gas car pull his tepee where he wants to go, soon they learn Indian’s way the best way; no good to stay in one place all of the time.”[108]

“When the Indian wants a squaw, he goes to her father and pays him his price; the white man takes one without pay to her father, but hires a preacher to tie her to him; when he is tired of her, he pays a lawyer to untie the rope so he can catch another one. Which good, which bad?” [109]

“The whites have got rich from controlling the colored people of the world but they got into debt to each other and now they fight among themselves. Soon they will destroy themselves and the original races will go on in the way the Great Spirit made them to do so.”[110]

“White people do not know how to handle fire. They make big fire and smoke and get little heat. Indians make little fire and get plenty heat. Their pipe is a high bowl with little hole for tobacco and a long stem. Little fire, little heat, smoke always cool when it gets to end of mouthpiece.” [111]

“The Great Spirit, the Sun, makes all life. Without it nothing would grow, no birds, no animals, no people. Indians go to the Happy Hunting Ground when they die. Whites do not know where they go when they die.” [112]

“White folks have so many different kinds of religion and churches and preachers the Indians could not tell which was good and which was no good. So they hold fast to their own.” [113]

“The whites tell the Indian that it is wrong to kill, to fight, to lie and steal or to drink strong liquor, and then they give him bad liquor and steal from him and lie to him and cheat him all the time.” [114]

“The whites got the Indians to sign away their land for strong drink. If you look at the record you will find what I say is true. All the country of America was got from the Indians for beads and rum or by cheating them.” [115]

“The white man’s fire-wagons (automobiles) kill more people every year than all the Indians killed in a hundred years.” [116]

“The white man thinks he is wise. The Indian thinks he is a fool. He kill all the buffalo and let them rot on the ground. Then he plow up the grass, puff, the wind blow the ground away. No grass, no buffalo, no pony, no Indian, all starve. White man is a fool. Indian fool too for he give the white man corn, potato, tobacco, tomato, all to make him rich. All the good the white man had got from the Indian. All the bad the Indian has got from the white man. Both fool.” [117]

“Gazing toward the big game country, the Chief was told that each year the people of the state paid more than a million dollars for the right to kill deer, and many of themselves. Much money for ticket. Indian kill just to get food, skins to make tepees, and moccasins and robes to keep warm. Never kill just for fun.” [118]

Final days and death

Chief Flying Hawk and his family did not enjoy the benefits of white men. His son Felix Flying Hawk, and later his grandson David Flying Hawk, had been cheated and jailed by the white man for stealing their own horses. Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull, his family and friends, had been assassinated. He had been placed on public exhibition as a specimen of the vanishing race to escape the poverty and constraints an Indian reservation. “He stroked his breast to show that he was poorly dressed. He was still wearing a coat and vest which had been given to him by the host on a previous visit. He said that if he had what was due him from the Government he could dress like other people, and have plenty to eat all the time, much of the time he was hungry and could not buy medicine or go to the doctor when sick.”[119] On March 5, 1929, at age seventy-five, Flying Hawk made his last visit to The Wigwam in Du Bois, Pennsylvania. He had been traveling with the circus, and the pony riding, war dances and inclement weather were weighing on his health. The Wigwam was good medicine. At The Wigwam he would could have fresh air, good food, rest and home comforts. Chief Flying Hawk died at Pine Ridge, South Dakota, December 24, 1931, at the age of 77 in want. He had written that during the previous winter of 1930-31 his little band was saved from starvation only through contributions from Gutzon Borglum and the American Red Cross. Sadly, it was rumored that Chief Flying Hawk died of starvation.[120]

Further reading

James A. Crutchfield, It Happened in Montana http://books.google.com/books?id=qmVCddIQ6yMC&printsec=frontcover&dq=it+happened+in+montana+by+james+a+crutchfield&source=bl&ots=COJBQlr1cJ&sig=zVBwjjJqG7_NmkGV22a4RGVy-ow&hl=en&ei=LlB9TeK8CY_urAGn1dHWBQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CB8Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

Richard G. Hardorff, Indian Views of the Custer Fight: A Source Book, http://books.google.com/books?id=QM_R7y5tAoIC&printsec=frontcover&dq=richard+g+hardorff+indian+views&source=bl&ots=ECBWeOiDgE&sig=rPuoQ_eipSBBwxmznojOxuyCvx8&hl=en&ei=gk99Tb7kKI_6swPv6_yIAw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&sqi=2&ved=0CBQQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

The Sioux at the Little Big Horn, http://custer.over-blog.com/article-10542515.html. Oglala Sioux Tribe, American Spirit, http://home.comcast.net/~zebrec/Chief_Flying_Hawk.htm

External links

Notes

- ↑ There has been confusion as to Chief Flying Hawk’s year of birth. The Chief notes in Firewater that he was born in 1852. However, the date is 1854. A photograph of Chief Flying Hawk in The Major Israel McCreight Collection notes on the backside, “ Moses Flying Hawk. Born in 1854. Told me he was born in 1852. M.I.M.” The official U.S. Census of Sioux men taken in March 1889 by Jim McLaughlin on the Standing Rock Agency, Lower Yanktonais, states that Flying Hawk was 35 years old at that time.

- ↑ Firewater, p.8-13. See Stevens, “Tiyospaye: An Oglala Genealogy Resource, http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~mikestevens/2010-p/p45.htm#i14346<

- ↑ Firewater, p.4. (c.1844-c.1928) http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~mikestevens/2010-p/p45.htm#i32854

- ↑ Firewater, p.131.

- ↑ Kingsley Bray,'"Notes on the Crazy Horse Genealogy: Part 1", http://www.american-tribes.com/Lakota/BIO/CrazyHorse-Part1.htm.

- ↑ Firewater, p. xv-xxi,115.

- ↑ Firewater, p.13.

- ↑ Firewater, p.12-13.

- ↑ Firewater, p.4

- ↑ Firewater, p.4-5.

- ↑ Firewater, p.5.

- ↑ Firewater, p.13.

- ↑ “When the Great Sioux War came we had lots of battles with the soldiers. We were fighting all the time with Miles and Crook and white soldiers every place we went. Firewater at p.11.

- ↑ “This was the last big trouble with the Indians and the soldiers and was in the winter in 1980. When the Indians would not come in from the Bad Lands, they got a big army together with plenty of clothing and supplies and camp-and-wagon equipment for a big campaign; they had enough soldiers to make a round-up of all the Indians they called hostiles. The government army, after many fights and loss of lives, succeeded in driving these starving Indians, with their families of women and gaunt-faced children, into a trap, where they could be forced to surrender their arms. This was on Wounded Knee Creek, northeast of Pine Ridge, and here the Indians were surrounded by the soldiers, who had Hotchkiss machine guns along with them. There were about four thousand Indians in this big camp, and the soldiers had the machine guns pointed at them from all around the village as the soldiers formed a ring about the tepees so that the Indians could not escape.” Firewater at p.123-124

- ↑ Edward Kadlecek and Mabell Kadlecek, “To Kill An Eagle: Indian Views on the Last Days of Crazy Horse” (hereinafter "Kadlecek"), 1981, p.40.

- ↑ “Young Black Fox was the half brother of Kicking Bear and Flying Hawk. On September 4, 1877, Young Black Fox commanded Crazy Horse’s warriors in his absence. The courage displayed on that occasion earned him the respect of both Indians and whites alike. In the same year Young Black Fox sought sanctuary in Canada, but he was killed on his return to the United States in 1881 by Indians of an enemy tribe. See McCreight, “Firewater and Forked Tongues: A Sioux Chief Interprets U.S. History”, (1947), p.4.

- ↑ Kadlecek, p.314.

- ↑ Kadlecek, p.39.

- ↑ Kadlecek, p.41.

- ↑ Kadlecek, p.41.

- ↑ Kadlecek, p.42.

- ↑ Heppler, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and the Progressive Image of American Indians”. Other major shows included Pawnee Bill, Cummins Wild West, Miller’s 101 Ranch and Sells-Floto Circus.

- ↑ Michele Delaney, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Warriors: A Photographic History by Gertrude Kasebier, Smithsonian National Museum of American History”, (hereinafter “Delaney”) (2007), p.21. “Wild West Shows and Images”, p.xiii.

- ↑ Firewater, p.41.

- ↑ Chief Flying Hawk replaces Chief Iron Tail who was stricken and died a fortnight ago. He was chosen by all of the braves yesterday. Boston Globe, June 12, 1916.

- ↑ Chief Flying Hawk’s Tales, p.11.

- ↑ Pageant organizers took a contingent of Show Indian veterans to Buffalo Bill's grave on Lookout Mountain, west of Denver. Denver's Chevrolet dealers provided the automobiles that carried the troupe to Buffalo Bill's Historical Museum. All the press-agents in Denver, however, could not replicate the genuine outpouring of emotion. A number of veterans spoke in Lakota. Johnny Baker, the former "Cowboy Kid" and Cody's foster son, translated. Flying Hawk laid his war staff of eagle feathers on the grave. Each of the Indians placed a buffalo nickel on the imposing stone as a symbol of the Indian, the buffalo, and the scout, figures since the 1880s that were symbolic of the early history of the American West. Speaking slowly, Spotted Weasel recited at length the virtues of his deceased friend. He told how Buffalo Bill, once an enemy of the Lakota, became in time their best friend among the Wasichus. Pahaska ("Long Hair") had clothed, fed, and given money to many of them, in friendship and the generosity that obliges it. To many others, he provided good jobs. "With his voice shaking with emotion which he made no effort to conceal," a reporter for the Denver Post wrote, Spotted Weasel "ended his eulogy with an appeal to his benefactor's spirit to be with him and his tribe." L. G. Moses, p. 257. Chief Flying Hawk’s Tales, p. 11.

- ↑ Delaney, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Warriors: A Photographic History by Gertrude Käsebier”, Smithsonian National Museum of American History (2007).

- ↑ M.I. McCreight, "Firewater and Forked Tongues: A Sioux Chief Interprets U.S. History", (1947), p.123-124, 131-139.

- ↑ Chief Flying Hawk replaces Chief Iron Tail who was stricken and died a fortnight ago. He was chosen by all of the braves yesterday. Boston Globe, June 12, 1916.

- ↑ Firewater, pp. 19-20.

- ↑ See The Wigwam: Puffs from the Peace Pipe at http://manycoups.net/PUFFS%20FROM%20THE%20PEACE%20PIPE_page1.htm.

- ↑ See Chief Flying Hawk's Tales at http://manycoups.net/ChiefFlyingHawksTales_page1.html.

- ↑ “I was thirty-two years old when I was made a Chief. A chief has to do many things before he is a Chief-so many brave deeds, so many scalps and so many horses. Many times I went out to a hill and stayed three days and three nights and did not eat or drink. Only just think about the best way to do things for my people.” Firewater, p.12-13.

- ↑ Firewater, p.xxiii-xxiv.

- ↑ McCreight “Manifesto”: Because we came to escape injustices, and were met by the original proprietors with a handshake, furnished food and shelter to us from starvation: Because we responded to these benefactors, not as Christians would, or were taught by the Man of Galilees to do, but by brutal and unprecedented savagery: Because we carried on a relentless campaign of extermination of them and all their rights and properties,(modern German style): Because we carried on this ruthless policy nearly three centuries, to the Massacre of Wounded Knee, to the final extermination of the race, except a tiny remnant still imprisoned in our back-lands called “reservations”; Because, nearly sixty years ago, the writer lived a dealt with them during the period of their greatest suffering. He saw first hand, the result of centuries old fighting to take from its original owners the whole of the territory comprising the United States, and it is to sketch lightly, the personality of some of the men who fought bravely to defend against unrighteous invasion of their homelands and the lives of their families, that this is written. November 1942. M.I McCreight, The Wigwam: Puffs From the Peace Pipe, "Because", (1943)

- ↑ Firewater, p. 14.

- ↑ Firewater, p.44.

- ↑ Firewater, p.8

- ↑ “Because this material was garnered over a long period of years in many interviews with Flying Hawk it would be impossible to arrange in chronological order. Rather the thought has been to preserve the flavor of its original telling. Excerpts from this manuscript have been privately published by the author in pamphlet form under the titles Chief Flying Hawk’s Tales (1936) and The Wigwam: Puffs From the Peace Pipe (1943).” Firewater and Forked Tongues, p. xiv-xv. Trail’s End Publishing Co., Pasadena, CA (1947)

- ↑ He gave his own interpretation of government dealings with Native Americans in the following passage from Theodore Roosevelt, The Winning of the West, Vol. 1, Appendix A to Chapter 4. (1889-96).