Flax in New Zealand

New Zealand Flax is a plant that has played an important part in the cultural and economic history of New Zealand for both the Māori people and the later European settlers. The two native species and their cultivars are also used as garden plants.

New Zealand Flax describes the common New Zealand perennial plants Phormium tenax and Phormium colensoi, known by the Māori names harakeke and wharariki respectively. They are quite distinct from the Northern Hemisphere plant known as flax (Linum usitatissimum), but the genus was given the common name 'flax' by Anglophone Europeans as it too could be used for its fibres.

Phormium produces long leaf fibres that have played an important role in the culture, history, and economy of New Zealand. P. tenax occurs naturally in New Zealand and Norfolk Island, while P. colensoi is endemic to New Zealand. Both species have been widely distributed to temperate regions of the world as economic fibre and ornamental plants.[1]

Constituents

The root of New Zealand Flax contains various chemical components, including anthraquinones (red crystalline compound) which has been obtained from the rhizomes, and tannin. The leaves contain hemicellulose polysaccharides (gum). The cytotoxic cucurbitacins have also been isolated from the leaves.[2] It was found that the chemistry of the gum to be built up of D-xylose and D-glucuronic acid units, which however gives no clue to the plant healing effects.[3] The seed oil is rich in linoleic acid, an 'essential' fatty acid.[2]

Traditional Māori uses

When the Māori came to New Zealand, they brought with them the paper mulberry plant from which they made bark cloth for clothing. The paper mulberry did not flourish and a substitute material was found in the native flax. As Captain Cook wrote: “Of the leaves of these plants, with very little preparation, they (the Māori) make all their common apparel; and of these they make also their strings, lines and cordage …”. They also made baskets, mats, and fishing nets from the undressed flax. The Māori practised advanced weft twining in phormium fibre cloaks.[4]

Plaiting and weaving (raranga) the flax fibres into baskets were but only two of the great variety of uses made of flax by Māori who recognised nearly 60 varieties, and who carefully propagated their own flax nurseries and plantations throughout the land. Leaves were cut near the base of the plant using a sharp mussel shell or specially shaped rocks, more often than not greenstone (jade, or pounamu). The green fleshy substance of the leaf was stripped off, again using a mussel shell, right through to the fibre which went through several processes of washing, bleaching, fixing, softening, dyeing and drying. The flax fibre, called muka, is laboriously washed, pounded and hand wrung to make soft for the skin. The cords (muka whenu) form the base cloth for intricate cloaks or garments (kākahu) such as the highly prized traditional feather cloak (kahu huruhuru). Different type of cloaks, such as Kahu Kiwi and Kahu Kākā, were produced by adorning them with colourful feathers from different native birds, such as kiwi, kākā (parrot), tui, huia and kererū (woodpigeon).

Fibres of various strengths were used to fashion eel traps (hinaki), surprisingly large fishing nets (kupenga) and lines, bird snares, cordage for ropes, baskets (kete), bags, mats, clothing, sandals (paraerae), buckets, food baskets (rourou), and cooking utensils etc. The handmade flax cording and ropes had such great tensile strength that they were used to successfully bind together sections of hollowed out logs to create huge ocean-going canoes (waka). With the help of wakas, pre-European Māori deployed seine nets which could be over one thousand metres long. The nets were woven from green flax, with stone weights and light wood or gourd floats, and could require hundreds of men to haul.[5] It was also used to make rigging, sails and lengthy anchor warps, and roofs for housing. Frayed ends of flax leaves were fashioned into torches and lights for use at night. The dried flower stalks, which are extremely light, were bound together with flax twine to make river rafts called mokihi.

-

Māori stone pestle for flax fibers

-

Flax fibers (muka)

-

Maori woman wearing the traditional costume made of flax fibre, c. 1880

-

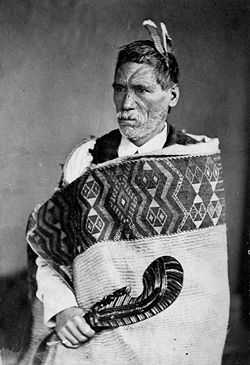

Photo of Rewi Manga Maniapoto in a flax cloak, 1879

Medical

For centuries, Māori have used nectar from the flowers for medicinal purposes and as a general sweetener. Boiled and crushed harakeke roots were applied externally as a poultice for boils, tumours and abscesses, as well as to varicose ulcers. Juice from pounded roots was used as a disinfectant, and taken internally to relieve constipation or expel worms. The pulp of pounded leaves was applied as dressings to bullet, bayonet or other wounds. The gum-like sap produced by harakeke contains enzymes that give it blood clotting and antiseptic qualities to help healing processes. It is a mild anaesthetic, and Māori traditionally applied the sap to boils and various wounds, to aching teeth, to rheumatic and associated pains, ringworm and various skin irritations, and scalds and burns. Splints were fashioned from korari (flower stalks) and leaves, and fine cords of muka fibre utilise the styptic properties of the gel before being used to stitch wounds. Harakeke is used as bandages and can secure broken bones much as plaster is used today.[6]

Defence

During the early Musket Wars and later New Zealand wars, Māori used large, thickly woven flax mats to cover entrances and lookout holes in their "gunfighter's pā" fortifications. Some warriors wore coats of heavily-plaited Phormium tenax, which gave defense characteristics similar to a medieval gambeson, slowing musket balls to be wounding rather than deadly.

Later uses

By the early 19th century the quality of rope materials made from New Zealand flax was known internationally,[7] as was the quality of New Zealand trees which were used for spars and masts. The Royal Navy was one of the largest customers. The flax trade burgeoned, especially after male Māori recognised the advantages of trade and adapted to helping in the harvesting and dressing of flax which had previously been done exclusively by females. "Whole tribes sometimes relocated to swamps where flax grew in abundance but where it was decidedly unhealthy to live. The taking of slaves increased - slaves who could be put to work dressing flax...".[8] A burgeoning flax industry developed with the fibres being used for rope, twine, matting, carpet under felt, and wool packs. Initially wild stands of flax were harvested but plantations were established with three in existence by 1851.[9] There was an active industry harvesting and processing flax at Foxton until demand declined due to the depression of the 1930s. John Stuart Yeates conducted a research program at the nearby Massey University (then Massey College). The flax industry went into decline in the 20th century and the last flax mill closed in 1985.

Since colonial times the fibre from Phormium tenax has been used for papermaking. Several times the possibility of commercial production has been investigated. Currently it is used by artists and craftsmen producing handmade papers.

See also

References

- ↑ Extraction, content, strength, and extension of Phormium variety fibres prepared for traditional Maori weaving, New Zealand Journal of Botany, 2000, Vol. 38: pg. 469.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Booker, S., Cambie, R., & Cooper, R. New Zealand medicinal plants. Reed, Auckland, 1987, p.91

- ↑ Booker, S., Cambie, R., & Cooper, R. New Zealand medicinal plants. Reed, Auckland, 1987), p.91

- ↑ John Gillow and Bryan Sentance, World Textiles: A Visual Guide to Traditional Techniques, London: Thames & Hudson, 2004, p. 64, 220.

- ↑ Meredith, Paul "Te hī ika – Māori fishing" Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Updated 2 March 2009.

- ↑ Brooker, S. G; R. C Cambie; Robert C Cooper (1987). New Zealand medicinal plants. Auckland, N.Z.: Reed. ISBN 9780790002507.

- ↑ "History of the Phormium Fibre Export Trade", 1966 "An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand"

- ↑ A dangerous people whose only occupation is war: Maori and Pakeha in 19th century New Zealand Journal of Pacific History, 1997, Christina A. Thompson

- ↑ Critchfield, Howard J. (Apr–Jun 1951). "Phormium tenax--New Zealand's Native Hard Fiber". Economic Botany (New York Botanical Garden Press) 5 (2): 172–184. doi:10.1007/bf02984775.

External links

- Department of Conservation

- Harakeke weaving varieties

- Flax and flax working at Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- Harakere/New Zealand Flax The Encyclopedia of Alternative & Natural Medicine