Flannan Isles

| Location | |

|---|---|

Flannan Isles Flannan Isles shown within the Outer Hebrides | |

| OS grid reference | NA720460 |

| Names | |

| Gaelic name |

|

| Meaning of name | Flannan Isles |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Lewis and Harris |

| Area | 58.87 hectares (145.5 acres) over more than seven islands.[1] |

| Area rank | Eilean Mòr is 325th [2] |

| Highest elevation | 88 m on Eilean Mòr |

| Political geography | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Na h-Eileanan Siar |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 0 |

| Largest settlement | Flannan Isles Lighthouse is the only habitable structure |

| References | [3][4] |

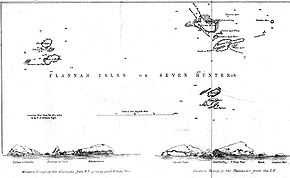

The Flannan Isles (Scottish Gaelic: Na h-Eileanan Flannach,[5] pronounced [nə ˈhelanən ˈflˠ̪an̪ˠəx]) or alternatively, the Seven Hunters are a small island group in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland, approximately 32 kilometres (20 mi) west of the Isle of Lewis. They may take their name from Saint Flannan, the seventh-century Irish preacher and abbot.[4] The islands have been devoid of permanent residents since the automation of Flannan Isles Lighthouse in 1971.[6] They are the location of an enduring mystery that occurred in December 1900, when all three lighthouse keepers vanished without trace.

Geography

The islands are split into three groups: the main cluster of rocks that lie to the northeast include the two principal islands of Eilean Mòr (Big Isle), which is approximately 17.5 hectares (43 acres) in extent,[4] and Eilean Taighe (House Isle); to the south lie Soray (Eastward Isle) and Sgeir Tomain; while the main western outcrops are Eilean a' Gobha (Isle of the Blacksmith), Roaireim (which has a natural rock arch), and Bròna Cleit (Sad Sunk Rock). The total land area amounts to approximately 50 hectares (120 acres) and the highest point is 88 metres (289 ft) above sea level on Eilean Mòr.[4]

The geology consists of a dark breccia of gabbros and dolerites intruding Archaean gneiss.[4] In prehistoric times, the area was covered by ice sheets that spread from Scotland out into the Atlantic Ocean. After the last retreat of the ice circa 20,000 years BP, sea levels were as much as 122 metres (400 ft) lower than at present and it is likely that the existing islands were part of a much larger land mass, although still separated from the Outer Hebrides by many miles of open water. Steadily rising sea levels thereafter would have reduced the land remaining above sea level to its present extent.[8]

There are two possible landing places for yachts visiting Eilean Mòr to the east and west, although this may be hazardous given the regular heavy swells.[4]

History

As the name implies, Eilean Taighe hosts a ruined stone shelter. Eilean Mòr is home to the lighthouse and a ruined chapel dedicated to St. Flannan, which the lighthouse keepers referred to as the "dog kennel" because of its small size. These ruined bothies were described collectively by the Ancient Monuments Commission as The Bothies of the Clan McPhail,[9] or Bothain Chlann ‘ic Phaill.[10] It is not entirely clear which St. Flannan the chapel honours. It is likely that the honoree was either the seventh century Abbot of Killaloe in County Clare or alternatively, the half brother of the eighth century St. Ronan who gave his name to the nearby island of North Rona. There was also a certain Flann, son of an Abbot of Iona, called Maol-duine, who died in 890 and may have loaned his name to these isolated isles.[4]

The archipelago also is known as 'The Seven Hunters'. During the Middle Ages they also may have been called the 'Seven Haley (Holy) Isles'.[11] Martin Martin (1703) lists a number of unusual customs associated with regular pilgrimages to Eilean Mòr, such as removing one's hat and making a sunwise turn when reaching the plateau.[12] It is possible that the saint or his acolytes lived on Eilean Mòr and perhaps, on Eilean Taighe as well. It is unlikely, however, that there were permanent residents on the islands once the Celtic Church fell into decline in the Hebrides (as a result of ninth century Viking invasions), until the construction of the lighthouse and its occupation very shortly before the dawn of the twentieth century.

Wildlife

The isles provide nesting for a population of seabirds, including Atlantic Puffins, Northern Fulmars, European Storm-petrels, Leach's Petrels, Common Shag, and Black-legged Kittiwakes. There is a gannetry on Roaireim.[10] From the late Middle Ages on, Lewismen regularly raided these nests for eggs, birds, and feathers. There is a population of rabbits, brought to the islands by the lighthouse keepers,[13] and crofters from Bernera graze sheep on the most fertile islands.[4] Minke and Pilot Whales, as well as Risso's and other species of dolphin are commonly observed in the vicinity.[10]

The islands became a Site of Special Scientific Interest in December 1983.[14]

Lighthouse

Designed by David Alan Stevenson, the 23-metre (75 ft) tower was constructed for the Northern Lighthouse Board (NLB) between 1895 and 1899 and it is located near the highest point on Eilean Mòr. Construction was undertaken by George Lawson of Rutherglen at a cost of £6,914 inclusive of the building of the landing places, stairs, railway tracks, etc. All of the materials used had to be hauled up the 45-metre (148 ft) cliffs directly from supply boats, no trivial task in the ever-churning Atlantic. A further £3,526 was spent on the shore station at Breasclete on the Isle of Lewis.[9] It was lit first on 7 December 1899.

In 1925, it was one of the first Scottish lights to receive communications from the shore by wireless telegraphy.[15] On 28 September 1971, it was automated. A reinforced concrete helipad was constructed at the same time to enable maintenance visits in heavy weather. The light is produced by burning acetylene gas and it has a range of 32 kilometres (20 mi). It now is monitored from the Butt of Lewis[6] and the shore station has been converted into flats.[16] Other than its relative isolation, it would be a relatively unremarkable light, were it not for the events that took place just over a year after it was commissioned.

Mystery of 1900

Discovery

The first hint of anything untoward on the Flannan Isles came on 15 December 1900. The steamer Archtor on passage from Philadelphia to Leith passed the islands in poor weather and noted that the light was not operational. This was reported on arrival at Oban, although no immediate action seems to have been taken. The island lighthouse was manned by a three-man team (Thomas Marshall, James Ducat, and Donald MacArthur), with a rotating fourth man spending time on shore. The relief vessel, the lighthouse tender Hesperus, was unable to set out on a routine visit from Lewis planned for 20 December due to adverse weather and did not arrive until noon on Boxing Day (26 December).[6] On arrival, the crew and relief keeper found that the flagstaff was bare of its flag, none of the usual provision boxes had been left on the landing stage for re-stocking, and more ominously, none of the lighthouse keepers were there to welcome them ashore. Jim Harvie, captain of the Hesperus, gave a strident blast on his whistle and set off a distress flare, but no reply was forthcoming.

A boat was launched and Joseph Moore, the relief keeper, was put ashore alone. He found the entrance gate to the compound and main door both closed, the beds unmade, and the clock stopped. Returning to the landing stage with this grim news, he then went back up to the lighthouse with the Hesperus's second-mate and a seaman. A further search revealed that the lamps were cleaned and refilled. A set of oilskins was found, suggesting that one of the keepers had left the lighthouse without them, which was surprising considering the severity of the weather on the date of the last entry in the lighthouse log. The only sign of anything amiss in the lighthouse was an overturned chair by the kitchen table. Of the keepers there was no sign, neither inside the lighthouse nor anywhere on the island.[17][6]

Moore and three volunteer seamen were left to attend the light and the Hesperus returned to the shore station at Breasclete. Captain Harvie sent a telegram to the Northern Lighthouse Board dated 26 December 1900, stating:

A dreadful accident has happened at the Flannans. The three keepers, Ducat, Marshall and the Occasional have disappeared from the Island... The clocks were stopped and other signs indicated that the accident must have happened about a week ago. Poor fellows they must have been blown over the cliffs or drowned trying to secure a crane or something like that.[6][17]

The men remaining on the island scoured every corner for clues as to the fate of the keepers. At the east landing everything was intact, but the west landing provided considerable evidence of damage caused by recent storms. A box at 33 metres (108 ft) above sea level had been broken and its contents strewn about; iron railings were bent over, the iron railway by the path was wrenched out of its concrete, and a rock weighing more than a ton had been displaced above that. On top of the cliff at more than 60 metres (200 ft) above sea level, turf had been ripped away as far as 10 metres (33 ft) from the cliff edge. The missing keepers had kept their log until 9 a.m. on 15 December, however, and their entries made it clear that the damage had occurred before the disappearance of the writers.[6][18]

Speculations and misconceptions

No bodies were ever found and the loneliness of the rocky islets may have lent itself to feverish imaginings. Theories abounded and resulted in "fascinated national speculation".[19] Some, simply were elaborations on the truth. For example, the events were commemorated in Wilfrid Wilson Gibson's 1912 ballad, Flannan Isle.[20] The poem refers erroneously to an uneaten meal laid out on the table, indicating that the keepers had been suddenly disturbed.

Yet, as we crowded through the door,

We only saw a table spread

For dinner, meat, and cheese and bread;

But, all untouch'd; and no-one there,

As though, when they sat down to eat,

Ere they could even taste,

Alarm had come, and they in haste

Had risen and left the bread and meat,

For at the table head a chair

Lay tumbled on the floor.[1]

- ^ Quotation from Nicholson (1995) p. 178.

However, Nicholson (1995) makes it clear that this does not square with Moore's recorded observations of the scene, which state that: "The kitchen utensils were all very clean, which is a sign that it must be after dinner some time they left."[6][21]

Other less plausible rumours ensued—that one keeper had murdered the other two and then thrown himself into the sea in a fit of remorse (which is likely not the case, simply because the keepers only had to work together for short amounts of time, and none of the men reported any psychotic behavior); that a sea serpent (or giant sea bird) had carried the men away; that they had been abducted by foreign spies; or that they had met their fate through the malevolent presence of a boat filled with ghosts—and the baleful influence of the "Phantom of the Seven Hunters" was widely suspected locally.[6]

Northern Lighthouse Board investigation

On 29 December 1900, Robert Muirhead, a Northern Lighthouse Board (NLB) superintendent, arrived to conduct the official investigation into the incident.

The explanation offered by Muirhead is more prosaic than the fanciful rumours suggested. He examined the clothing left behind in the lighthouse and concluded that James Ducat and Thomas Marshall had gone down to the western landing stage, and that Donald MacArthur (the 'Occasional') had left the lighthouse during heavy rain in his shirt sleeves. He noted that whoever left the light last and unattended, was in breach of NLB rules.[6] He also noted that some of the damage to the west landing was “difficult to believe unless actually seen”.[20]

From evidence which I was able to procure I was satisfied that the men had been on duty up till dinner time on Saturday the 15th of December, that they had gone down to secure a box in which the mooring ropes, landing ropes etc. were kept, and which was secured in a crevice in the rock about 110 ft (34 m) above sea level, and that an extra large sea had rushed up the face of the rock, had gone above them, and coming down with immense force, had swept them completely away.[22]

Whether this explanation brought any comfort to the families of the lost keepers is unknown. The deaths of Thomas Marshall, James Ducat (who left a widow and four children), and Donald MacArthur (who left a widow and two children) cast a shadow over the lighthouse service for many years.[20]

Later theories and interpretations

Nicholson (1995) offers an alternative idea for the demise of the keepers. The coastline of Eilean Mòr is deeply indented with narrow gullies called geos. The west landing, which is situated in such a geo, terminates in a cave. In high seas or storms, water would rush into the cave and then explode out again with considerable force. Nicholson speculates that McArthur may have seen a series of large waves approaching the island, and knowing the likely danger to his colleagues, ran down to warn them, only to suffer the same fate as well.[23] This theory has the advantages of explaining the over-turned chair, and the set of oilskins remaining indoors,[6] although perhaps, not the closed door and gate.[4]

Haswell-Smith (2004) attributes the origins of the theory to Walter Aldebert, a keeper on the Flannans from 1953–1957. Aldebert believed one man may have been washed into the sea, that his companion rushed back to the light for help but that both would-be rescuers also were washed away by a second freak wave.[4]

The event remains a popular issue of contention among those who are interested in paranormal activity. Inevitably perhaps, modern imaginations speculate about abduction by aliens.[19] A fictional use of this idea is the basis for the Doctor Who serial Horror of Fang Rock.[24] The mystery also was the inspiration for the composer Peter Maxwell Davies's modern chamber opera The Lighthouse (1979).[25] The British rock group Genesis wrote and recorded "The Mystery of Flannan Isle Lighthouse" in 1968 while working on their first album, but it was not released until 1998 in Genesis Archive 1967-75.[26] Angela J. Elliott wrote a novel which was published in 2005 about the disappearance of the lighthouse keepers, it was entitled Some Strange Scent of Death after a line from Gibson's poem.[27] The "haunted" islands and the lighthouse also feature heavily as a hideout for a villain in British author Manda Benson's novel, Pilgrennon's Beacon.[28] In 2008, the New Zealand band Beltane wrote a song about the lighthouse and its mysterious disappearances on the album ...Through Darker Seasons.[29]

See also

- Mary Celeste

- Missing persons

- List of people who have mysteriously disappeared

- Draupner wave

- Neil M. Gunn - an episode in his novel The Silver Darlings takes place on Eilean Mòr

References

- McCloskey, Keith. (1 July 2014) "The Lighthouse: The Mystery of the Eilean Mor Lighthouse Keepers", Stroud, the History Press.ISBN 978-0750953658

- Bathhurst, Bella. (2000) The Lighthouse Stevensons. London. Flamingo. ISBN 0-00-653076-1

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- Harvie-Brown, J. A. & Buckley, T. E. (1889), A Vertebrate Fauna of the Outer Hebrides. Edinburgh. David Douglas.

- Martin, Martin (1703) A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland including A Voyage to St. Kilda Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- Murray, W.H. (1973) The Islands of Western Scotland. London. Eyre Methuen. SBN 413303802

- Munro, R.W. (1979) Scottish Lighthouses. Stornoway. Thule Press. ISBN 0-906191-32-7

- Nicholson, Christopher. (1995) Rock Lighthouses of Britain: The End of an Era? Caithness. Whittles. ISBN 1-870325-41-9

- Perrot, D. et al. (1995) The Outer Hebrides Handbook and Guide. Machynlleth. Kittiwake. ISBN 0-9511003-5-1

Notes

- ↑ "SPA description:Flannan Isles". JNCC. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ↑ Area and population ranks: there are c. 300 islands >20ha in extent and 93 permanently inhabited islands were listed in the 2011 census.

- ↑ General Register Office for Scotland (28 November 2003) Scotland's Census 2001 – Occasional Paper No 10: Statistics for Inhabited Islands. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. pp. 329–31. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- ↑ Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2003) Ainmean-àite/Placenames. (pdf) Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 Nicholson (1995) pp. 168–79.

- ↑ Harvie-Brown & Buckley (1889) facing p. XXIV

- ↑ Murray (1973) pp. 68–69.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Flannan Isles Lighthouse " Northern Lighthouse Board. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Western Isles Guide Book: Flannan Islands. Charles Tait photographic Ltd. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- ↑ Munro, Sir Donald (1594) Description of the Western Isles of Scotland.

- ↑ Martin (1703) pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Murray (1973) p. 108.

- ↑ Scottish Natural Heritage list of SSSIs. (pdf) SNH. Retrieved 28 December 2006.

- ↑ Munro (1979) p. 223.

- ↑ Perrot, D. et al. (1995) p. 132.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Transcripts from documents related to the Flannan Isles mystery. Museum of Scottish Lighthouses/Wayback. Original retrieved 3 September 2008, Wayback version retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ↑ Munro (1979) pp. 170–71.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Bathhurst (2000) p. 249.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Munro (1979) p. 171.

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) nonetheless states: “A meal of cold meat, pickles and potatoes was untouched on the kitchen table.”

- ↑ Munro (1979) pages 170–71, although Nicholson (1995), Bathhurst (2000) and Haswell-Smith (2004) quote the same report using somewhat different language: "After a careful examination of the place.... I am of the opinion that the most likely explanation of the disappearance of the men is that they had all gone down on the afternoon of Saturday, 15 December to the proximity of the west landing to secure the box with the mooring ropes etc. and that an unexpectedly large roller had come up on the island, and that a large body of water going up higher than where they were and coming down upon them, swept them away with resistless force.”

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) suggests these events are "very rare”.

- ↑ "The Mystery of Flannan Isle" bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- ↑ "Opera: 'The Lighthouse' by Davies" New York Times. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ↑ "The Mystery Of The Flannan Isle Lighthouse (Demo 1968)". Yahoo.com. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- ↑ Elliott, Angela J (2005). Some Strange Scent of Death. Whittles. ISBN 978-1-904445-15-9.

- ↑ Benson, Manda, (2011) Pilgrennon's Beacon. Tangentrine. ISBN 978-0-9566080-2-4.

- ↑ ...Through_Darker_Seasons Encyclopaedia Metallum. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

External links

- Northern Lighthouse Board information about Flannan Isles lighthouse

- Northern Lighthouse Board information about the disappearance of the keepers

- The Vanishing Lighthousemen of Eilean Mór Investigative paper based on primary sources

| ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Coordinates: 58°17′N 07°35′W / 58.283°N 7.583°W