Fisher's method

In statistics, Fisher's method,[1][2] also known as Fisher's combined probability test, is a technique for data fusion or "meta-analysis" (analysis of analyses). It was developed by and named for Ronald Fisher. In its basic form, it is used to combine the results from several independent tests bearing upon the same overall hypothesis (H0).

Application to independent test statistics

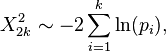

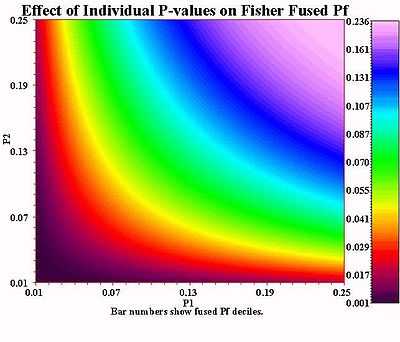

Fisher's method combines extreme value probabilities from each test, commonly known as "p-values", into one test statistic (X2) using the formula

where pi is the p-value for the ith hypothesis test. When the p-values tend to be small, the test statistic X2 will be large, which suggests that the null hypotheses are not true for every test.

When all the null hypotheses are true, and the pi (or their corresponding test statistics) are independent, X2 has a chi-squared distribution with 2k degrees of freedom, where k is the number of tests being combined. This fact can be used to determine the p-value for X2.

The distribution of X2 is a chi-squared distribution for the following reason. Under the null hypothesis for test i, the p-value pi follows a uniform distribution on the interval [0,1]. The negative natural logarithm of a uniformly distributed value follows an exponential distribution. Scaling a value that follows an exponential distribution by a factor of two yields a quantity that follows a chi-squared distribution with two degrees of freedom. Finally, the sum of k independent chi-squared values, each with two degrees of freedom, follows a chi-squared distribution with 2k degrees of freedom.

Limitations of independent assumption

Dependence among statistical tests is generally positive, which means that the p-value of X2 is too small (anti-conservative) if the dependency is not taken into account. Thus, if Fisher's method for independent tests is applied in a dependent setting, and the p-value is not small enough to reject the null hypothesis, then that conclusion will continue to hold even if the dependence is not properly accounted for. However, if positive dependence is not accounted for, and the meta-analysis p-value is found to be small, the evidence against the null hypothesis is generally overstated. The mean false discovery rate,  ,

,  reduced for

reduced for  independent or positively correlated tests, may suffice to control alpha for useful comparison to an over-small p-value from Fisher's X2.

independent or positively correlated tests, may suffice to control alpha for useful comparison to an over-small p-value from Fisher's X2.

Extension to dependent test statistics

In cases where the tests are not independent, the null distribution of X2 is more complicated. A common strategy is to approximate the null distribution with a scaled χ2-distribution random variable. Different approaches may be used depending on whether or not the covariance between the different p-values is known.

Brown's method [3] is designed to combine dependent p-values with known covariance while Kost's method [4] is designed to combine dependent p-values with unknown covariance.

Interpretation

Fisher's method is typically applied to a collection of independent test statistics, usually from separate studies having the same null hypothesis. The meta-analysis null hypothesis is that all of the separate null hypotheses are true. The meta-analysis alternative hypothesis is that at least one of the separate alternative hypotheses is true.

In some settings, it makes sense to consider the possibility of "heterogeneity," in which the null hypothesis holds in some studies but not in others, or where different alternative hypotheses may hold in different studies. A common reason for the latter form of heterogeneity is that effect sizes may differ among populations. For example, consider a collection of medical studies looking at the risk of a high glucose diet for developing type II diabetes. Due to genetic or environmental factors, the true risk associated with a given level of glucose consumption may be greater in some human populations than in others.

In other settings, the alternative hypothesis is either universally false, or universally true – there is no possibility of it holding in some settings but not in others. For example, consider several experiments designed to test a particular physical law. Any discrepancies among the results from separate studies or experiments must be due to chance, possibly driven by differences in power.

In the case of a meta-analysis using two-sided tests, it is possible to reject the meta-analysis null hypothesis even when the individual studies show strong effects in differing directions. In this case, we are rejecting the hypothesis that the null hypothesis is true in every study, but this does not imply that there is a uniform alternative hypothesis that holds across all studies. Thus, two-sided meta-analysis is particularly sensitive to heterogeneity in the alternative hypotheses. One sided meta-analysis can detect heterogeneity in the effect magnitudes, but focuses on a single, pre-specified effect direction.

Relation to Stouffer's Z-score method

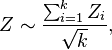

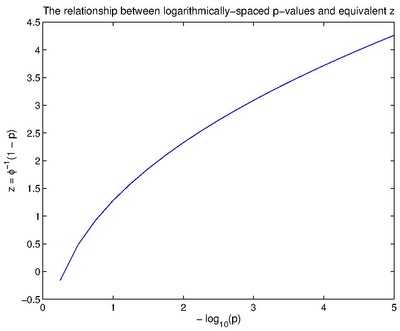

A closely related approach to Fisher's method is based on Z-scores rather than p-values.[5] If we let Zi = Φ − 1(1−pi), where Φ is the standard normal cumulative distribution function, then

is a Z-score for the overall meta-analysis. This Z-score is appropriate for one-sided right-tailed p-values; minor modifications can be made if two-sided or left-tailed p-values are being analyzed. This method is named for the sociologist Samuel A. Stouffer.

Since Fisher's method is based on the average of −log(pi) values, and the Z-score method is based on the average of the Zi values, the relationship between these two approaches follows from the relationship between z and −log(p) = −log(1−Φ(z)). For the normal distribution, these two values are not perfectly linearly related, but they follow a highly linear relationship over the range of Z-values most often observed, from 1 to 5. As a result, the power of the Z-score method is nearly identical to the power of Fisher's method.

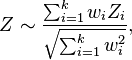

One advantage of the Z-score approach is that it is straightforward to introduce weights. [6][7] If the ith Z-score is weighted by wi, then the meta-analysis Z-score is

which follows a standard normal distribution under the null hypothesis. While weighted versions of Fisher's statistic can be derived, the null distribution becomes a weighted sum of independent chi-squared statistics, which is less convenient to work with.

Implemented in R, a functions to compute Fisher's X2 and Stouffer's (weighted) Z and their p-values is:

Stouffer.test <- function(p, w) { # p is a vector of p-values if (missing(w)) { w <- rep(1, length(p))/length(p) } else { if (length(w) != length(p)) stop("Length of p and w must equal!") } Zi <- qnorm(1-p) Z <- sum(w*Zi)/sqrt(sum(w^2)) p.val <- 1-pnorm(Z) return(c(Z = Z, p.value = p.val)) } Fisher.test <- function(p) { Xsq <- -2*sum(log(p)) p.val <- pchisq(Xsq, df = 2*length(p), lower.tail = FALSE) return(c(Xsq = Xsq, p.value = p.val)) } p <- c(.01, .2, .3) Stouffer.test(p = p) # p-value = 0.017 Fisher.test(p = p) # p-value = 0.022

References

- ↑ Fisher, R.A. (1925). Statistical Methods for Research Workers. Oliver and Boyd (Edinburgh). ISBN 0-05-002170-2.

- ↑ Fisher, R.A.; Fisher, R. A (1948). "Questions and answers #14". The American Statistician 2 (5): 30–31. doi:10.2307/2681650. JSTOR 2681650.

- ↑ Brown, M. (1975). "A method for combining non-independent, one-sided tests of significance". Biometrics 31 (4): 987–992. doi:10.2307/2529826.

- ↑ Kost, J.; McDermott, M. (2002). "Combining dependent P-values". Statistics & Probability Letters 60 (2): 183–190. doi:10.1016/S0167-7152(02)00310-3.

- ↑ Stouffer, S.A.; E.A. Suchman, L.C. DeVinney, S.A. Star, R.M. Jr. Williams (1949). The American Soldier, Vol.1: Adjustment during Army Life. Princeton University Press, Princeton,.

- ↑ Mosteller, F.; Bush, R.R. (1954). "Selected quantitative techniques". In Lindzey, G. Handbook of Social Psychology,Vol1. Addison_Wesley, Cambridge, Mass. pp. 289–334.

- ↑ Liptak, T. (1958). "On the combination of independent tests". Magyar Tud. Akad. Mat. Kutato Int. Kozl. 3: 171–197.