First Triumvirate

|

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Rome and the fall of the Republic |

|---|

The First Triumvirate was a political alliance between two prominent Roman politicians (triumvirs) which included Gaius Julius Caesar, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great. "Pompey and Ceasar now formed a pact, jointly swearing to oppose all legislation of which any one of them might disapprove. One lasting from approximately 59 BCE to Crassus' defeat by the Parthians in 53 BCE.[1] The alliance was "not at heart a union of those with the same political ideals and ambitions", but one where "all [were] seeking personal advantage."[2]

Creation

Marcus Licinius Crassus and Pompey the Great had been colleagues in the consulship in 70 BC, when they had legislated the full restoration of the tribunate of the people.[3] However, since that time, the two men had entertained considerable antipathy for one another, each believing the other to have gone out of his way to increase his own reputation at his colleague's expense.[4] Caesar contrived to reconcile the two men, and then combined their clout with his own to have himself elected consul in 59 BC; as Goldsworthy notes, it would take all of "Caesar's persuasiveness and charm to convince the old enemies" that he could give them they wanted if they both joined in supporting him.[5] Caesar and Crassus were already allies, Crassus already having made "substantial loans" to Caesar),[6] and he solidified his alliance with Pompey—his political motivation—by giving his daughter, Julia, in marriage.[7] Each triumvir had their own reasons for joining together; per Goldsworthy, "Pompey wanted land for his veterans and... ratification of his eastern settlement… Crassus... relief for the tax collectors of Asia… [Caesar] needed powerful backers if he was to achieve anything."[8]

The Triumvirate was kept secret until the Senate obstructed Caesar's proposed agrarian law establishing colonies of Roman citizens, and the associated distribution of portions of the public lands (ager publicus).[9] He promptly brought the law before the Council of the People in a speech that found him flanked by Crassus and Pompey, whose enthusiastic support thus revealed the alliance.[10] Caesar's agrarian law was carried through, and the Triumviri then proceeded to allow the demagogue Publius Clodius Pulcher's election as tribune of the people, successfully ridding themselves both of Marcus Tullius Cicero and Cato the Younger, both adamant opponents of the Triumviri.

The senate offered resistance in ways that it could; it awarded Caesar, as a snub to his dealings in the Triumvirate, "the woods and paths of Italy" as his proconsul territory.

The Triumvirate proceeded to make further arrangements for itself; through a tribune, Caesar passed his own ruling on the proconsul territory matter, the triumvirate naming him proconsul of both Gauls (Gallia Cisalpina and Gallia Transalpina), and of the Roman province of Illyricum, with command of four legions, for five years. Caesar's new father-in-law, Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, was made consul for the year 58 BC.

By 56 BC, the bonds between the three men were fraying,[11] so Caesar invited Crassus, then Pompey, to a secret meeting, the Lucca Conference, to rethink their joint strategy, a meeting that renewed their political alliance. They agreed that Pompey and Crassus would again stand for the consulship in 55 BC; once elected, they would extend Caesar's command in Gaul by five years. At the end of their joint consular year, Pompey would keep Hispania in absentia, and Crassus would have the influential and lucrative governorship of Syria and use it as a base to conquer Parthia[12][13][14][15][16][17]

The alliance allowed the triumvirs to dominate Roman politics completely, but it would not last indefinitely due to the ambitions, egos, and jealousies of the three. Caesar and Crassus were implicitly "hand-in-glove", but Pompey disliked Crassus and grew increasingly envious of Caesar's spectacular successes in the Gallic War, whereby he annexed the whole of the Three Gauls to Rome.

Death of Crassus and Pompey

Julia's death during childbirth and Crassus's ignominious defeat and death at Carrhae at the hands of the Parthians in 53 BC effectively undermined the alliance. Pompey remained in Rome, governing his Spanish provinces through lieutenants, and remained in virtual control of the city throughout that time. He gradually drifted further and further from his alliance with Caesar, eventually marrying the daughter of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius Cornelianus Scipio Nasica, one of the boni ("Good Men"), an archconservative faction of the Senate steadfastly opposed to Caesar.

Pompey was elected consul without colleague in 52 BC, and took part in the politicking which led to Caesar's crossing of the Rubicon in 49 BC, starting the Civil War. Pompey was made commander-in-chief of the war by the Senate, and was defeated by his former ally Caesar at Pharsalus. Pompey's subsequent murder in Egypt in an inept political intrigue left Caesar sole master of the Roman world.

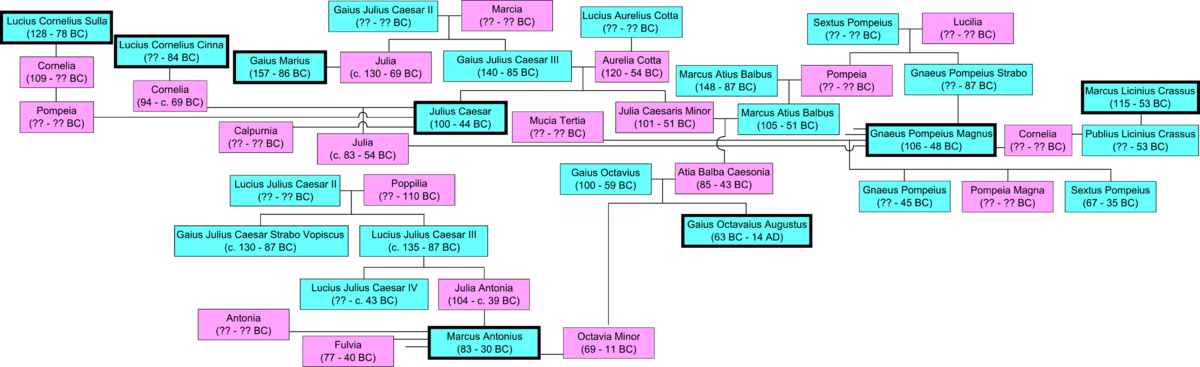

Family tree

See also

Notes and citations

- ↑ Toynbee, Encyclopedia Britannica "Julius Caesar (Roman ruler)," §"The first triumvirate...," and §"Antecedents and outcome…".

- ↑ Goldsworthy, p. 164.

- ↑ Goldsworthy, p. 94

- ↑ Goldsworthy, p. UNKNOWN; "Although Pompey and Crassus had combined to seek office and cooperated in the restoration of the tribunate, their mutual dislike and envy swiftly resurfaced."

- ↑ Goldsworthy, p. UNKNOWN.

- ↑ Goldsworthy, p. 81.

- ↑ Goldsworthy, p. 174.

- ↑ Goldsworthy, p. 166.

- ↑ Goldsworthy, p. 167; "A commission would oversee the purchase and distribution of the land to both Pompey's veteran soldiers and large numbers of the urban poor."

- ↑ Goldsworthy, p. 170; "Both enthusiastically supported the bill, for the first time giving a clear public indication of the association with the consul."

- ↑ Boak, History of Rome to 565 A.D., pg. 169.

- ↑ Cicero, Letters to his brother Quintus, see 2.3, accessed UNKNOWN.

- ↑ Suetonius, "Julius" in Twelve Caesars, see 24, accessed UNKNOWN.

- ↑ Plutarch, "Caesar" in Lives, see 21, accessed UNKNOWN.

- ↑ Plutarch, "Crassus" in Lives, see 14–15, accessed UNKNOWN.

- ↑ Plutarch, "Pompey" in Lives, see 51, accessed UNKNOWN.

- ↑ Boatwright, et al. pg. 229.

Literature cited

- Boak, Arthur E.R. (1925). History of Rome to 565 A.D., New York:Macmillan, see , accessed 18 April 2015.

- Boatwright, Mary T.; Daniel J. Gargola & Richard J. A. Talbert (2004). The Romans: From Village to Empire, Oxford, UK:Oxford University Press, ISBN 0195118758, see , accessed 18 April 2015.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2008). Caesar: Life of a Colossus. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300126891.

- Suetonius [Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus] (2003). The Twelve Caesars, with an introduction by Michael Grant. [Robert Graves, Transl.] (Rev. ed.). London, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 0140449213. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- Toynbee, Arnold Joseph (2014). "Julius Caesar (Roman ruler): The first triumvirate and the conquest of Gaul," and "Julius Caesar (Roman ruler): Antecedents and outcome of the civil war of 49–45 bcd," at Encyclopedia Britannica (online), see and , accessed 18 April 2015.

External links

- Herodotuswebsite.co.uk - an article on how the First Triumvirate came into being. (Site no longer active, please refer to this link, accessed via the Wayback Machine)