Fermat's theorem on sums of two squares

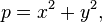

In additive number theory, Pierre de Fermat's theorem on sums of two squares states that an odd prime p is expressible as

with x and y integers, if and only if

For example, the primes 5, 13, 17, 29, 37 and 41 are all congruent to 1 modulo 4, and they can be expressed as sums of two squares in the following ways:

On the other hand, the primes 3, 7, 11, 19, 23 and 31 are all congruent to 3 modulo 4, and none of them can be expressed as the sum of two squares.

Albert Girard was the first to make the observation, describing all positive integral numbers (not necessarily primes) expressible as the sum of two squares of positive integers; this was published posthumously in 1634.[1] Fermat was the first to claim a proof of it; he announced this theorem in a letter to Marin Mersenne dated December 25, 1640: for this reason this theorem is sometimes called Fermat's Christmas Theorem.

Since the Brahmagupta–Fibonacci identity implies that the product of two integers each of which can be written as the sum of two squares is itself expressible as the sum of two squares, by applying Fermat's theorem to the prime factorization of any positive integer n, we see that if all the prime factors of n congruent to 3 modulo 4 occur to an even exponent, then n is expressible as a sum of two squares. The converse also holds.[2] This equivalence provides the characterization Girard guessed.

Proofs of Fermat's theorem on sums of two squares

Fermat usually did not write down proofs of his claims, and he did not provide a proof of this statement. The first proof was found by Euler after much effort and is based on infinite descent. He announced it in two letters to Goldbach, on May 6, 1747 and on April 12, 1749; he published the detailed proof in two articles (between 1752 and 1755).[3][4] Lagrange gave a proof in 1775 that was based on his study of quadratic forms. This proof was simplified by Gauss in his Disquisitiones Arithmeticae (art. 182). Dedekind gave at least two proofs based on the arithmetic of the Gaussian integers. There is an elegant proof using Minkowski's theorem about convex sets. Simplifying an earlier short proof due to Heath-Brown (who was inspired by Liouville's idea), Zagier presented a one-sentence proof of Fermat's assertion.[5]

Related results

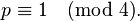

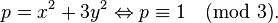

Fermat announced two related results fourteen years later. In a letter to Blaise Pascal dated September 25, 1654 he announced the following two results for odd primes  :

:

He also wrote:

- If two primes which end in 3 or 7 and surpass by 3 a multiple of 4 are multiplied, then their product will be composed of a square and the quintuple of another square.

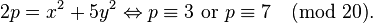

In other words, if p, q are of the form 20k + 3 or 20k + 7, then pq = x2 + 5y2. Euler later extended this to the conjecture that

Both Fermat's assertion and Euler's conjecture were established by Lagrange.

See also

- Proofs of Fermat's theorem on sums of two squares

- Legendre's three-square theorem

- Lagrange's four-square theorem

Notes

- ↑ L. E. Dickson, History of the Theory of Numbers, Vol. II, Ch. VI, p. 227.

- ↑ For a proof of the converse see for instance 20.1, Theorems 367 and 368, in: G.H. Hardy and E.M. Wright. An introduction to the theory of numbers, Oxford 1938.

- ↑ De numerus qui sunt aggregata quorum quadratorum. (Novi commentarii academiae scientiarum Petropolitanae 4 (1752/3), 1758, 3-40)

- ↑ Demonstratio theorematis FERMATIANI omnem numerum primum formae 4n+1 esse summam duorum quadratorum. (Novi commentarii academiae scientiarum Petropolitanae 5 (1754/5), 1760, 3-13)

- ↑ Zagier, D. (1990), "A one-sentence proof that every prime p ≡ 1 (mod 4) is a sum of two squares", American Mathematical Monthly 97 (2): 144, doi:10.2307/2323918, MR 1041893.

References

- L. E. Dickson. History of the Theory of Numbers Vol. 2. Chelsea Publishing Co., New York 1920

- Stillwell, John. Introduction to Theory of Algebraic Integers by Richard Dedekind. Cambridge University Library, Cambridge University Press 1996. ISBN 0-521-56518-9

- D. A. Cox (1989). Primes of the Form x2 + ny2. Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 0-471-50654-0.