Fatty acid synthesis

Fatty acid synthesis is the creation of fatty acids from acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA precursors through action of enzymes called fatty acid synthases. It is an important part of the lipogenesis process, which – together with glycolysis – functions to create fats from blood sugar in living organisms.

Straight-chain fatty acids

Straight-chain fatty acids occur in two types: saturated and unsaturated.

Saturated straight-chain fatty acids

Much like β-oxidation, straight-chain fatty acid synthesis occurs via the six recurring reactions shown below, until the 16-carbon palmitic acid is produced.[1][2]

The diagrams presented show how fatty acids are synthesized in microorganisms and list the enzymes found in Escherichia coli.[1] These reactions are performed by fatty acid synthase II (FASII), which in general contain multiple enzymes that act as one complex. FASII is present in prokaryotes, plants, fungi, and parasites, as well as in mitochondria.[3]

In animals, as well as yeast and some fungi, these same reactions occur on fatty acid synthase I (FASI), a large dimeric protein that has all of the enzymatic activities required to create a fatty acid. FASI is less efficient than FASII; however, it allows for the formation of more molecules, including "medium-chain" fatty acids via early chain termination.[3]

Once a 16:0 carbon fatty acid has been formed, it can undergo a number of modifications, resulting in desaturation and/or elongation. Elongation, starting with stearate (18:0), is performed mainly in the ER by several membrane-bound enzymes. The enzymatic steps involved in the elongation process are principally the same as those carried out by FAS, but the four principal successive steps of the elongation are performed by individual proteins, which may be physically associated.[4][5]

| Step | Enzyme | Reaction | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | Acetyl CoA:ACP transacylase | |

Activates acetyl CoA for reaction with malonyl-ACP |

| (b) | Malonyl CoA:ACP transacylase | |

Activates malonyl CoA for reaction with acetyl-ACP |

| (c) | 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthetase |  |

Reacts priming acetyl-ACP with chain-extending malonyl-ACP. |

| (d) | 3-ketoacyl-ACP reductase | |

Reduces the carbon 3 ketone to a hydroxyl group |

| (e) | 3-Hydroxyacyl ACP dehydrase | |

Removes water |

| (f) | Enoyl-ACP reductase | |

Reduces the C2-C3 double bond. |

Abbreviations: ACP – Acyl carrier protein, CoA – Coenzyme A, NADP – Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate.

Regulation

Acetyl-CoA is formed into malonyl-CoA by acetyl-CoA carboxylase, at which point malonyl-CoA is destined to feed into the fatty acid synthesis pathway. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase is the point of regulation in saturated straight-chain fatty acid synthesis, and is subject to both phosphorylation and allosteric regulation. Regulation by phosphorylation occurs mostly in mammals, while allosteric regulation occurs in most organisms. Allosteric control occurs as feedback inhibition by palmitoyl-CoA and activation by citrate. When there are high levels of palmitoyl-CoA, the final product of saturated fatty acid synthesis, it allosterically inactivates acetyl-CoA carboxylase to prevent a build-up of fatty acids in cells. Citrate acts to activate acetyl-CoA carboxylase under high levels, because high levels indicate that there is enough acetyl-CoA to feed into the Krebs cycle and produce energy.[6]

De Novo Synthesis in Humans

In humans, fatty acids are formed predominantly in the liver and lactating mammary glands, and, to a lesser extent, the adipose tissue. Most acetyl-CoA is formed from pyruvate by pyruvate dehydrogenase in the mitochondria. Acetyl-CoA produced in the mitochondria is condensed with oxaloacetate by citrate synthase to form citrate, which is then transported into the cytosol and broken down to yield acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate by ATP citrate lyase. Oxaloacetate in the cytosol is reduced to malate by cytoplasmic malate dehydrogenase, and malate is transported back into the mitochondria to participate in the Citric acid cycle.[7]

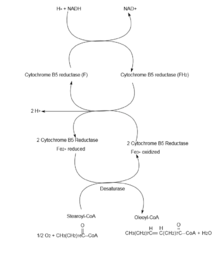

Desaturation

Desaturation of fatty acids involves a process that requires molecular oxygen (O2), NADH, and cytochrome b5. The reaction, which occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum, results in the oxidation of both the fatty acid and NADH. The most common desaturation reactions involve the placement of a double bond between carbons 9 and 10 (as in the conversion of palmitic acid to palmitoleic acid and the conversion of stearic acid to oleic acid, facilitated by the action of Δ9-desaturase). Other positions that can be desaturated in humans include carbon 4, 5, and 6, via Δ4-, Δ5-, and Δ6-desaturases, respectively.

Unsaturated fatty acids are essential components to prokaryotic and eukaryotic cell membranes. These fatty acids function primarily in maintaining membrane fluidity.[8] They have also been associated with serving as signaling molecules in other processes such as cell differentiation and DNA replication.[8] There are two pathways organisms use for desaturation: Aerobic and Anaerobic.

Anaerobic desaturation

Many bacteria use the anaerobic pathway for synthesizing unsaturated fatty acids. This pathway does not utilize oxygen and is dependent on enzymes to insert the double bond before elongation utilizing the normal fatty acid synthesis machinery. In Escherichia coli, this pathway is well understood.

- FabA is a β-hydroxydecanoyl-ACP dehydrase – it is specific for the 10-carbon saturated fatty acid synthesis intermediate (β-hydroxydecanoyl-ACP).

- FabA catalyzes the dehydration of β-hydroxydecanoyl-ACP, causing the release of water and insertion of the double bond between C7 and C8 counting from the methyl end. This creates the trans-2-decenoyl intermediate.

- Either the trans-2-decenoyl intermediate can be shunted to the normal saturated fatty acid synthesis pathway by FabB, where the double bond will be hydrolyzed and the final product will be a saturated fatty acid, or FabA will catalyze the isomerization into the cis-3-decenoyl intermediate.

- FabB is a β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase that elongates and channels intermediates into the mainstream fatty acid synthesis pathway. When FabB reacts with the cis-decenoyl intermediate, the final product after elongation will be an unsaturated fatty acid.[9]

- The two main unsaturated fatty acids made are Palmitoleoyl-ACP (16:1ω7) and cis-vaccenoyl-ACP (18:1ω7).[10]

Most bacteria that undergo anaerobic desaturation contain homologues of FabA and FabB.[11] Clostridia are the main exception; they have a novel enzyme, yet to be identified, that catalyzes the formation of the cis double bond.[10]

Regulation

This pathway undergoes transcriptional regulation by FadR and FabR. FadR is the more extensively studied protein and has been attributed bifunctional characteristics. It acts as an activator of fabA and fabB transcription and as a repressor for the β-oxidation regulon. In contrast, FabR acts as a repressor for the transcription of fabA and fabB.[9]

Aerobic desaturation

Aerobic desaturation is the most widespread pathway for the synthesis of unsaturated fatty acids. It is utilized in all eukaryotes and some prokaryotes. This pathway utilizes desaturases to synthesize unsaturated fatty acids from full-length saturated fatty acid substrates.[12] All desaturases require oxygen and ultimately consume NADH even though desaturation is an oxidative process. Desaturases are specific for the double bond they induce in the substrate. In Bacillus subtilis, the desaturase, Δ5-Des, is specific for inducing a cis-double bond at the Δ5 position.[8][12] Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains one desaturase, Ole1p, which induces the cis-double bond at Δ9.[8]

Regulation

In B. subtilis, this pathway is regulated by a two-component system: DesK and DesR. DesK is a membrane-associated kinase and DesR is a transcriptional regulator of the des gene.[8][12] The regulation responds to temperature; when there is a drop in temperature, this gene is upregulated. Unsaturated fatty acids increase the fluidity of the membrane and stabilize it under lower temperatures. DesK is the sensor protein that, when there is a decrease in temperature, will autophosphorylate. DesK-P will transfer its phosphoryl group to DesR. Two DesR-P proteins will dimerize and bind to the DNA promoters of the des gene and recruit RNA polymerase to begin transcription.[8][12]

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

In general, both anaerobic and aerobic unsaturated fatty acid synthesis will not occur within the same system, however Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Vibrio ABE-1 are exceptions.[13][14][15] While P. aeruginosa undergoes primarily anaerobic desaturation, it also undergoes two aerobic pathways. One pathway utilizes a Δ9-desaturase (DesA) that catalyzes a double bond formation in membrane lipids. Another pathway uses two proteins, DesC and DesB, together to act as a Δ9-desaturase, which inserts a double bond into a saturated fatty acid-CoA molecule. This second pathway is regulated by repressor protein DesT. DesT is also a repressor of fabAB expression for anaerobic desaturation when in presence of exogenous unsaturated fatty acids. This functions to coordinate the expression of the two pathways within the organism.[14][16]

Branched-chain fatty acids

Branched-chain fatty acids are usually saturated and are found in two distinct families: the iso-series and anteiso-series. It has been found that Actinomycetales contain unique branch-chain fatty acid synthesis mechanisms, including that which forms tuberculosteric acid.

Branch-chain fatty acid synthesizing system

The branched-chain fatty acid synthesizing system uses α-keto acids as primers. This system is distinct from the branched-chain fatty acid synthetase that utilizes short-chain acyl-CoA esters as primers.[17] α-Keto acid primers are derived from the transamination and decarboxylation of valine, leucine, and isoleucine to form 2-methylpropanyl-CoA, 3-methylbutyryl-CoA, and 2-Methylbutyryl-CoA, respectively.[18] 2-Methylpropanyl-CoA primers derived from valine are elongated to produce even-numbered iso-series fatty acids such as 14-methyl-pentadecanoic (isopalmitic) acid, and 3-methylbutyryl-CoA primers from leucine may be used to form odd-numbered iso-series fatty acids such as 13-methyl-tetradecanoic acid. 2-Methylbutyryl-CoA primers from isoleucine are elongated to form anteiso-series fatty acids containing an odd number of carbon atoms such as 12-Methyl tetradecanoic acid.[19] Decarboxylation of the primer precursors occurs through the branched-chain α-keto acid decarboxylase (BCKA) enzyme. Elongation of the fatty acid follows the same biosynthetic pathway in Escherichia coli used to produce straight-chain fatty acids where malonyl-CoA is used as a chain extender.[20] The major end products are 12–17 carbon branched-chain fatty acids and their composition tends to be uniform and characteristic for many bacterial species.[19]

BCKA decarboxylase and relative activities of α-keto acid substrates

The BCKA decarboxylase enzyme is composed of two subunits in a tetrameric structure (A2B2) and is essential for the synthesis of branched-chain fatty acids. It is responsible for the decarboxylation of α-keto acids formed by the transamination of valine, leucine, and isoleucine and produces the primers used for branched-chain fatty acid synthesis. The activity of this enzyme is much higher with branched-chain α-keto acid substrates than with straight-chain substrates, and in Bacillus species its specificity is highest for the isoleucine-derived α-keto-β-methylvaleric acid, followed by α-ketoisocaproate and α-ketoisovalerate.[19][20] The enzyme’s high affinity toward branched-chain α-keto acids allows it to function as the primer donating system for branched-chain fatty acid synthetase.[20]

| Substrate | BCKA activity | CO2 Produced (nmol/min mg) | Km (μM) | Vmax (nmol/min mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-α-keto-β-methyl-valerate | 100% | 19.7 | <1 | 17.8 |

| α-Ketoisovalerate | 63% | 12.4 | <1 | 13.3 |

| α-Ketoisocaproate | 38% | 7.4 | <1 | 5.6 |

| Pyruvate | 25% | 4.9 | 51.1 | 15.2 |

Factors affecting chain length and pattern distribution

α-Keto acid primers are used to produce branched-chain fatty acids that, in general, are between 12 and 17 carbons in length. The proportions of these branched-chain fatty acids tend to be uniform and consistent among a particular bacterial species but may be altered due to changes in malonyl-CoA concentration, temperature, or heat-stable factors (HSF) present.[19] All of these factors may affect chain length, and HSFs have been demonstrated to alter the specificity of BCKA decarboxylase for a particular α-keto acid substrate, thus shifting the ratio of branched-chain fatty acids produced.[19] An increase in malonyl-CoA concentration has been shown to result in a larger proportion of C17 fatty acids produced, up until the optimal concentration (≈20μM) of malonyl-CoA is reached. Decreased temperatures also tend to shift the fatty-acid distribution slightly toward C17 fatty-acids in Bacillus species.[17][19]

Branch-chain fatty acid synthase

This system functions similarly to the branch-chain fatty acid synthesizing system, however it uses short-chain carboxylic acids as primers instead of alpha-keto acids. In general, this method is used by bacteria that do not have the ability to perform the branch-chain fatty acid system using alpha-keto primers. Typical short-chain primers include isovalerate, isobutyrate, and 2-methyl butyrate. In general, the acids needed for these primers are taken up from the environment; this is often seen in ruminal bacteria.[21]

The overall reaction is:

- Isobutyryl-CoA + 6 malonyl-CoA +12 NADPH + 12H+ → Isopalmitic acid + 6 CO2 12 NADP + 5 H2O + 7 CoA[17]

The difference between (straight-chain) fatty acid synthase and branch-chain fatty acid synthase is substrate specificity of the enzyme that catalyzes the reaction of acyl-CoA to acyl-ACP.[17]

Omega-alicyclic fatty acids

Omega-alicyclic fatty acids typically contain an omega-terminal propyl or butyryl cyclic group and are some of the major membrane fatty acids found in several species of bacteria. The fatty acid synthetase used to produce omega-alicyclic fatty acids is also used to produce membrane branched-chain fatty acids. In bacteria with membranes composed mainly of omega-alicyclic fatty acids, the supply of cyclic carboxylic acid-CoA esters is much greater than that of branched-chain primers.[17] The synthesis of cyclic primers is not well understood but it has been suggested that mechanism involves the conversion of sugars to shikimic acid which is then converted to cyclohexylcarboxylic acid-CoA esters that serve as primers for omega-alicyclic fatty acid synthesis [21]

Tuberculostearic acid synthesis

Tuberculostearic acid (D-10-Methylstearic acid) is a saturated fatty acid that is known to be produced by Mycobacterium spp. and two species of Streptomyces. It is formed from the precursor oleic acid (a monosaturated fatty acid).[22] After oleic acid is esterified to a phospholipid, S-adenosyl-methionine donates a methyl group to the double bond of oleic acid.[23] This methylation reaction forms the intermediate 10-methylene-octadecanoyal. Successive reduction of the residue, with NADPH as a cofactor, results in 10-methylstearic acid [18]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Dijkstra, Albert J., R. J. Hamilton, and Wolf Hamm. "Fatty Acid Biosynthesis." Trans Fatty Acids. Oxford: Blackwell Pub., 2008. 12. Print.

- ↑ "MetaCyc pathway: superpathway of fatty acids biosynthesis (E. coli)".

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Fatty Acids: Straight-chain Saturated, Structure, Occurrence and Biosynthesis." Lipid Library – Lipid Chemistry, Biology, Technology and Analysis. Web. 30 Apr. 2011. <http://lipidlibrary.aocs.org/lipids/fa_sat/index.htm>.

- ↑ "MetaCyc pathway: stearate biosynthesis I (animals)".

- ↑ "MetaCyc pathway: very long chain fatty acid biosynthesis II".

- ↑ Diwan, Joyce J. "Fatty Acid Synthesis." Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) :: Architecture, Business, Engineering, IT, Humanities, Science. Web. 30 Apr. 2011. <http://rpi.edu/dept/bcbp/molbiochem/MBWeb/mb2/part1/fasynthesis.htm>.

- ↑ Ferre, P.; F. Foufelle (2007). "SREBP-1c Transcription Factor and Lipid Homeostasis: Clinical Perspective". Hormone Research 68 (2): 72–82. doi:10.1159/000100426. PMID 17344645. Retrieved 2010-08-30.

this process is outlined graphically in page 73

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Aguilar, Pablo S, and Diegode Mendoza. "Control of fatty acid desaturation: a mechanism conserved from bacteria to humans." Molecular microbiology 62.6 (2006):1507–14.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Feng, Youjun, and John ECronan. "Complex binding of the FabR repressor of bacterial unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis to its cognate promoters." Molecular microbiology 80.1 (2011):195–218.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Zhu, Lei, et al. "Functions of the Clostridium acetobutylicium FabF and FabZ proteins in unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis." BMC microbiology 9(2009):119.

- ↑ Wang, Haihong, and John ECronan. "Functional replacement of the FabA and FabB proteins of Escherichia coli fatty acid synthesis by Enterococcus faecalis FabZ and FabF homologues." Journal of biological chemistry 279.33 (2004):34489-95.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Mansilla, Mara C, and Diegode Mendoza. "The Bacillus subtilis desaturase: a model to understand phospholipid modification and temperature sensing." Archives of microbiology 183.4 (2005):229-35.

- ↑ Wada, M, N. Fukunaga, and S. Sasaki. "Mechanism of biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids in Pseudomonas sp. strain E-3, a psychrotrophic bacterium." Journal of bacteriology 171.8 (1989):4267-71.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Subramanian, Chitra, Charles ORock, and Yong-MeiZhang. "DesT coordinates the expression of anaerobic and aerobic pathways for unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa." Journal of bacteriology 192.1 (2010):280-5.

- ↑ Morita, N, et al. "Both the anaerobic pathway and aerobic desaturation are involved in the synthesis of unsaturated fatty acids in Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1." FEBS letters 297.1–2 (1992):9–12.

- ↑ Zhu, Kun, et al. "Two aerobic pathways for the formation of unsaturated fatty acids in Pseudomonas aeruginosa." Molecular microbiology 60.2 (2006):260-73.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Kaneda, Toshi. "Iso- and Anteiso-Fatty Acids in Bacteria: Biosynthesis, Function, and Taxonomic Significance." Microbiological Reviews 55.2 (1991): 288–302

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Branched-chain Fatty Acids, Phytanic Acid, Tuberculostearic Acid Iso/anteiso- Fatty Acids." Lipid Library – Lipid Chemistry, Biology, Technology and Analysis. Web. 1 May 2011. http://lipidlibrary.aocs.org/lipids/fa_branc/index.htm.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 Naik, Devaray N., and Toshi Kaneda. "Biosynthesis of Branched Long-chain Fatty Acids by Species of Bacillus: Relative Activity of Three α-keto Acid Substrates and Factors Affecting Chain Length." Can. J. Microbiol. 20 (1974): 1701–708.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Oku, Hirosuke, and Toshi Kaneda. "Biosynthesis of Branched-chain Fatty Acids in Bacillis Subtilis." The Journal of Biological Chemistry 263.34 (1988): 18386-8396.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Christie, William W. "Fatty Acids: Natural Alicyclic Structures, Occurrence, and Biochemistry." The AOCS Lipid Library. 5 Apr. 2011. Web. 24 Apr. 2011. <http://lipidlibrary.aocs.org/lipids/fa_cycl/file.pdf>.

- ↑ Ratledge, Colin, and John Stanford. The Biology of the Mycobacteria. London: Academic, 1982. Print.

- ↑ Kubica, George P., and Lawrence G. Wayne. The Mycobacteria: a Sourcebook. New York: Dekker, 1984. Print.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||