Faro (card game)

|

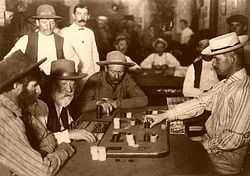

Men playing faro in an Arizona saloon in 1895. | |

| Origin | France |

|---|---|

| Type | Gambling |

| Players | Np. |

| Skill(s) required | Counting |

| Cards | 52 |

| Deck | Anglo-American |

| Play | Clockwise |

| Playing time | 10–15 min. |

| Random chance | Medium |

| Related games | |

| Baccarat | |

Faro, Pharaoh, or Farobank is a late 17th-century French gambling card game. It is descended from basset, and belongs to the lansquenet and Monte Bank family of games due to the use of a banker and several players. Winning or losing occurs when cards turned up by the banker match those already exposed.

It is not a direct relative of poker, but faro was often just as popular, due to its fast action, easy-to-learn rules, and better odds than most games of chance. The game of faro is played with only one deck of cards and admits any number of players.

History

France

The earliest references to a card game named pharaon are found in Southwestern France during the reign of Louis XIV. Basset was outlawed in 1691, and pharaoh emerged several years later as a derivative of basset, before it too was outlawed.[1]

England

Despite the French ban, pharaoh and basset continued to be widely played in England during the 18th century. Pharo, the English alternate spelling of Pharaoh,[2] was easy to learn, quick and, when played honestly, the odds for a player were the best of all gambling games, as records Gilly Williams in a letter to George Selwyn in 1752.[3]

United States

With its name shortened to faro, it soon spread to the United States in the 19th century to become the most widespread and popularly favored gambling game. It was played in almost every gambling hall in the Old West from 1825 to 1915.[4] Faro could be played in over 150 places in Washington, DC alone during the Civil War.[5] An 1882 study considered faro to be the most popular form of gambling, surpassing all others forms combined in terms of money wagered each year.[1]

The faro game was also called "bucking the tiger" or "twisting the tiger's tail", which comes from early card backs that featured a drawing of a Bengal tiger. By the mid 19th century, the tiger was so commonly associated with the game that gambling districts where faro was popular became known as "tiger town", or in the case of smaller venues, "tiger alley".[6] In fact, some gambling houses would simply hang a picture of a tiger in their windows to advertise that a game could be found within.

Faro's detractors regarded it as a dangerous scam that destroyed families and reduced men to poverty because of rampant rigging of the dealing box. Crooked faro equipment was so popular that many sporting-house companies began to supply gaffed dealing boxes specially designed so that the bankers could cheat their players. Cheating was prevalent enough that editions of Hoyle’s Rules of Games began their faro section warning readers that not a single honest faro bank could be found in the United States. Although the game became scarce after World War II, it continued to be played at a few Las Vegas and Reno casinos through 1985.

Criminal prosecutions of faro were involved in the Supreme Court cases of United States v. Simms, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 252 (1803), and Ex parte Milburn, 34 U.S. (9 Pet.) 704 (1835).

Etymology

Historians have suggested that the name Pharaon comes from Louis XIV's royal gamblers, who chose the name from the motif that commonly adorned one of the French-made court cards.[2]

Rules

Description

A game of faro was often called a "faro bank". It was played with an entire deck of playing cards. One person was designated the "banker" and an indeterminate number of players, known as "punters", could be admitted. Chips (called "checks") were purchased by the punter from the banker (or house) from which the game originated. Bet values and limits were set by the house. Usual check values were 50 cents to $10 each.

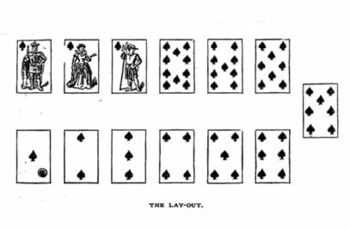

The faro table was typically oval,[7] covered with green baize, and had a cutout for the banker. A board was placed on top of the table with one suit of cards (traditionally the suit of spades) pasted to it in numerical order, representing a standardized betting "layout". Each player laid his stake on one of the 13 cards on the layout. Players could place multiple bets and could bet on multiple cards simultaneously by placing their bet between cards or on specific card edges. Players also had the choice of betting on the “high card” bar located at the top of the layout.

Procedure

- A deck of cards was shuffled and placed inside a "dealing box", a mechanical device also known as a "shoe", which was used to prevent manipulations of the draw by the banker and intended to assure players of a fair game.

- The first card in the dealing box was called the "soda" and was "burned off", leaving 51 cards in play. The dealer then drew 2 cards: the first was called the "banker's card" and was placed on the right side of the dealing box. The next card after the banker's card was called the carte Anglaise (English card) or simply the "player's card", and it was placed on the left of the shoe.[5]

- The banker's card was the "losing card"; regardless of its suit, all bets placed on the layout's card that had the same denomination as the banker's card were lost by the players and won by the bank. The player's card was the "winning card". All bets placed on the card that had that denomination were returned to the players with a 1 to 1 (even money) payout by the bank (e.g. a dollar bet won a dollar). A “high card” bet won if the player’s card had a higher value than the banker’s card.[6] The dealer settled all bets after each two cards drawn. This allowed players to bet before drawing the next two cards. Bets that neither won nor lost remained on the table, and could be picked up or changed by the player prior to the next draw.

- A player could reverse the intent of his bet by placing a hexagonal (6-sided) token called a "copper" on it. Some histories said a penny was sometimes used in place of a copper. This was known as "coppering" the bet, and reversed the meaning of the win/loss piles for that particular bet.

- When only 3 cards remained in the dealing box, the dealer would "call the turn", which was a special type of bet that occurred at the end of each round. The object now was to predict the exact order that the 3 remaining cards, Bankers, Players, and the final card called the Hock, would be drawn.[5] The player's odds here were 5 to 1, while a successful bet paid off at 4 to 1 (or 1 to 1 if there were a pair among the 3, known as a "cat-hop"). This provided one of the dealer's few advantages in faro. If it happened that the 3 remaining cards were all the same, there would be no final bet, as the outcome was not in question.

A device, called a "casekeep" was employed to assist the players and prevent dealer cheating by counting cards. The casekeep resembled an abacus, with one spindle for each card denomination, with 4 counters on each spindle. As a card was played, either winning or losing, one of 4 counters would be moved to indicate that a card of that denomination had been played. This allowed players to plan their bets by keeping track of what cards remained available in the dealing box. The operator of the case keep is called the "casekeeper", or colloquially in the American West, the "coffin driver".

Certain advantages were reserved to the banker: if he drew a doublet, that is, two equal cards, he won half of the stakes upon the card which equaled the doublet. In a fair game, this provided the only "house edge". If the banker drew the last card of the pack, he was exempt from doubling the stakes deposited on that card.[8] These and the advantage from the odds on the turn bet provided a slight financial advantage to the dealer or house. To give themselves more of an advantage, and to counter the losses from players cheating, the dealers would also often cheat as well.[1]

Cheating

In a fair game the house's edge was low, so bankers increasingly resorted to cheating the players to increase the profitability of the game for the house. This too was acknowledged by Hoyle editors when describing how faro banks were opened and operated: "To justify the initial expenditure, a dealer must have some permanent advantage."[1]

By dealers

Dealers employed several methods of cheating:

- Stacked or rigged decks: A stacked deck would consist of many paired cards, allowing the dealer to claim half of the bets on that card, as per the rules. A rigged deck would contain textured cards that allowed dealers to create paired cards in the deck while giving the illusion of thorough shuffling.[1]

- Rigged dealing boxes: Rigged, or "gaffed", dealing boxes came in several variants. Typically, they allowed the dealer to see the next card prior to the deal, by use of a small mirror or prism visible only to the dealer. If the next card was heavily bet, the box could also allow the dealer to draw 2 cards in one draw, thus hiding the card that would have paid.[1] This would result in the casekeep not accounting for the hidden card, however. If the casekeeper were employed by the house, though, he could take the blame for "accidentally" not logging that card when it was drawn.

- Sleight of hand: In concert with the rigged dealing box, the dealer could, when he knew the next card to win, surreptitiously slide a player's bet off of the winning card if it was on the dealer's side of the layout. At a hectic faro table he could often get away with this, though it was obviously a risky move if caught.

By players

Players would routinely cheat as well. Their techniques employed distraction and sleight-of-hand, and usually involved moving their stake to a winning card, or at the very least off of the losing card, without being detected.[1] Their methods ranged from crude to creative, and worked best at a busy, fast-paced table:

- Simple move of their bet: The most basic cheat was simply to move one's bet to the adjacent card on the layout while avoiding the banker noticing. While the simplest, it also carried the greatest risk of detection.

- Moving with a thread: A silk thread or single horse hair would be affixed to the bottom check in the bet, and allowed the stack to be pulled across the table to another card on the layout. This was less risky, as the cheating player would not have to make an overt action.

- Removing the copper: A variant on the use of the thread was to affix it to the copper token used to reverse the bet. If the losing card matched the player's bet, the copper made it a winning bet and no cheat was needed. If, however, the winning card, dealt second, were to match the player's bet the copper would ordinarily make it a loser, but quickly snatching the copper from the stack with the invisible thread turned it into a winner. This held the least risk, as once the copper was yanked from the stack, there was no thread left attached to the bet.

Being caught cheating often resulted in a fight, or even gunfire.[1]

In culture

Etymology

- The old phrase "from soda to hock", meaning "from beginning to end" derives from the first and last cards dealt in a round of faro.[9] The phrase evolved to the better known "from soup to nuts".

- In turn, "soda" and "hock" are probably themselves derived from "hock and soda," a popular nineteenth-century drink consisting of hock (a sweet German wine) combined with soda water.

Geography

- The town of Faro, Yukon was named after the game.

History

- The 18th century adventurer and author Casanova was known to be a great player of faro. He mentions the game several times in his autobiography.

- The 18th century a Prussian officer, adventurer, and author Friedrich Freiherr von der Trenck makes mention of playing faro in his memoirs (February 1726 – 25 July 1794).

- The 18th century Whig radical Charles James Fox preferred faro to any other game.

- The 19th century American con man Soapy Smith was a faro dealer. It was said that every faro table in Soapy's Tivoli Club in Denver, Colorado, in 1889 was gaffed (made to cheat).

- The 19th century scam artist Canada Bill Jones loved the game so much that, when he was asked why he played at one game that was known to be rigged, he replied, "It's the only game in town."

- The 19th century lawman Wyatt Earp dealt faro for a short time after arriving in Tombstone Arizona having acquired controlling interest in a game out of the Oriental saloon.[10]

- The 19th century dentist and gambler John "Doc" Holliday dealt faro in the Bird Cage Theater as an additional source of income while living in Tombstone, Arizona.[11]

Fiction

- In a famous scene from War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy, Nicholas Rostov loses 43,000 rubles to Dolokhov playing Faro.

- Faro is central to the plot of Alexander Pushkin's story "The Queen of Spades" and Tchaikovsky's opera The Queen of Spades.

- The miners in Puccini's opera La Fanciulla del West play a contentious game of faro in Act One.

- In the second Act of the opera The Tales of Hoffmann by Jacques Offenbach, Giulietta invites Schlemil to takes his place at the table of Pharaoh.

- Lord Strongmore in John William Polidori's The Vampyre plays Faro in Brussels.

- In Show Boat by Edna Ferber, the gambler Gaylord Ravenal specializes in the game of Faro.

- In Oliver La Farge's 1935 story "Spud and Cochise", the cowboy Spud plays Faro when he is in a very good mood. Aware of the widespread dishonesty of American Faro dealers in his time, he nevertheless bets heavily, viewing his gambling losses as a form of charity.

- Numerous references to faro are made in the Western radio drama Gunsmoke, starring William Conrad.

- When planning The Sting on New York gangster Doyle Lonnegan (Robert Shaw), one of the conmen researching their mark mentions that he "only goes out to play faro" making him a hard target for the big con.

- Numerous references to faro are made in the 21st century HBO television series Deadwood.

- In Misfortune by Wesley Stace, Pharaoh is named after his father's profession, a faro dealer.

- The episode "Staircase to Heaven" in the television series Murdoch Mysteries involves a murder during a game of Faro.

- In Thackeray's novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon the main character runs a crooked faro bank, alternatively to his great fortune or ruin.

- In the film Tombstone, Wyatt Earp, played by Kurt Russell, becomes a faro dealer at the Oriental soon after arriving in Tombstone.

- Faro is mentioned extensively in John D. Fitzgerald's semi-autobiographical Silverlode/Adenville trilogy, which consists of the books Papa Married a Mormon, Mama's Boarding House and Uncle Will and the Fitzgerald Curse. It is one of the primary games played at the Whitehorse Saloon, owned by the character of Uncle Will. In Mama's Boarding House the character of Floyd Thompson, one of the tenants in the boarding house, is a Faro dealer. Faro is also occasionally mentioned in Fitzgerald's corresponding Great Brain series, which focuses on the children of Adenville.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 "Faro card game - Cheating at faro".

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Scarne, John Scarne on Card Games: How to Play and Win at Poker, Pinochle, Blackjack, Gin and Other Popular Card Games pg. 163 Dover Publications (2004) ISBN 0-486-43603-9

- ↑ Blackwood's Edinburgh magazine vol. 15 pg. 176 London 1844

Our life here would not displease you, for we eat and drink well,

and the Earl of Coventry holds a Pharaoh-bank every night to us,

which we have plundered considerably. - ↑ Oxford Dictionary of Card Games, p. 16, David Parlett – Oxford University Press 1996 ISBN 0-19-869173-4

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "How to play faro". Bicycle Playing Cards.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Faro, or Bucking the Tiger". Legends of America.

- ↑ The hand-book of games, p. 336, H.G. Bohn – Bell & Daldy, London 1867

- ↑ The book of card games, p. 121, Peter Arnold – Barnes & Noble 1995 ISBN 1-56619-950-6

- ↑ "Soda to hock: The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable". Oxford Reference.

- ↑ William M. Breakenridge,Richard Maxwell Brown Helldorado: bringing the law to the mesquite pg. 171 University of Nebraska Press (1992) ISBN 0-8032-6100-4

- ↑ Wesley Treat, Mark Moran, Mark Sceurman Weird Arizona: Your Travel Guide to Arizona's Local Legends and Best Kept Secrets pg. 190 Sterling (2007) ISBN 1-4027-3938-9

Further reading

- Tom and Judy Dawson, The Hochman Encyclopedia of American Playing Cards, Stamford, CT: US Games Systems Inc., 2000. ISBN 1-57281-297-4 (Gives historical account of Faro cards in the US, extensively illustrated.)

- John Nevil Maskelyne, Sharps and Flats, (London: 1894; reprint, Las Vegas: GBC. ISBN 978-0-89650-912-2

- J. R. Sanders, "Faro: Favorite Gambling Game of the Frontier", Wild West Magazine, October 1996

External links

- Newspaper articles: 1880s games of chance Faro, Poker, Keno, Spanish Monte, Stud, Nutshell, Deadwood Poker blog

- "Former dealer hopes for return of faro", Las Vegas Review-Journal

- Wichita Faro - Online faro game