Factory Acts

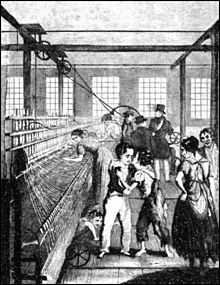

The Factory Acts were a series of Acts passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom to regulate the conditions of industrial employment. The early Acts concentrated on regulating the hours of work and moral welfare of young children employed in cotton mills but were effectively unenforced until the Act of 1833 established a professional Factory Inspectorate. The regulation of working hours was then extended to women by an Act of 1844. An Act in 1847 (the Ten Hour Act) (together with Acts in 1850 and 1853 remedying defects in the 1847 Act) met a long- standing (and by 1847 well-organised) demand by the millworkers for a ten-hour day. The Factory Acts also sought to ameliorate the conditions under which mill-children worked with requirements on ventilation, sanitation, and guarding of machinery. Introduction of the ten-hour day proved to have none of the dire consequences predicted by its opponents, and its apparent success effectively ended theoretical objections to the principle of factory legislation; from the 1860s onwards more industries were brought within the Factory Act, until by 1910, Sidney Webb reviewing the cumulative effect of century of factory legislation felt able to write

The system of regulation which began with the protection of the tiny class of pauper apprentices in textile mills now includes within its scope every manual worker in every manufacturing industry. From the hours of labour and sanitation, the law has extended to the age of commencing work, protection against accidents, mealtimes and holidays, the methods of remuneration, and in the United Kingdom as well as in the most progressive of English-speaking communities, to the rate of wages itself. The range of Factory Legislation has, in fact, in one country or another, become co-extensive with the conditions of industrial employment. No class of manual-working wage-earners, no item in the wage-contract, no age, no sex, no trade or occupation, is now beyond its scope. This part, at any rate, of Robert Owen's social philosophy has commended itself to the practical judgment of the civilised world. It has even, though only towards the latter part of the nineteenth century, converted the economists themselves -converted them now to a " legal minimum wage " — and the advantage of Factory Legislation is now as soundly " orthodox " among the present generation of English, German, and American professors as " laisser-faire " was to their predecessors. ... Of all the nineteenth century inventions in social organisation, Factory Legislation is the most widely diffused.[1]:Preface

He also commented on the gradual (accidentally almost Fabian) way this transformation had been achieved

The merely empirical suggestions of Dr. Thomas Percival and the Manchester Justices of 1784 and 1795, and the experimental legislation of the elder Sir Robert Peel in 1802, were expanded by Robert Owen in 1815 into a general principle of industrial government, which came to be applied in tentative instalments by successive generations of Home Office administrators. ... This century of experiment in Factory Legislation affords a typical example of English practical empiricism. We began with no abstract theory of social justice or the rights of man. We seem always to have been incapable even of taking a general view of the subject we were legislating upon. Each successive statute aimed at remedying a single ascertained evil. It was in vain that objectors urged that other evils, no more defensible existed in other trades, or among other classes, or with persons of ages other than those to which the particular Bill applied. Neither logic nor consistency, neither the over-nice consideration of even-handed justice nor the Quixotic appeal of a general humanitarianism, was permitted to stand in the way of a practical remedy for a proved wrong. That this purely empirical method of dealing with industrial evils made progress slow is scarcely an objection to it. With the nineteenth century House of Commons no other method would have secured any progress at all.[1]:Preface

Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802

The Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802 (42 Geo III c.73) was introduced by Sir Robert Peel ; it addressed concerns felt by the medical men of Manchester about the health and welfare of children employed in cotton mills, and first expressed by them in 1784 in a report on an outbreak of 'putrid fever' at a mill at Radcliffe owned by Peel. Although the Act included some hygiene requirements for all textile mills, it was largely concerned with the employment of apprentices; it left the employment of 'free' (non-indentured) children unregulated. It allowed (but did not require) local magistrates to enforce compliance with its requirements, and therefore went largely unenforced. As the first attempt to improve the lot of factory children, it is often seen as paving the way for future Factory Acts. At best, it only partially paved the way; its restriction to apprentices (where there was a long tradition of legislation) meant that it was left to later Factory Acts to establish the principle of intervention by Parliament on humanitarian grounds on worker welfare issues against the "laissez-faire" political and economic orthodoxy of the age which held that to be ill-advised.

Under the Act, regulations and rules came into force on 2 December 1802 and applied to all textile mills and factories employing three or more apprentices or twenty employees. The buildings must have sufficient windows and openings for ventilation, and should be cleaned at least twice yearly with quicklime and water; this included ceilings and walls.[2]

Each apprentice was to be given two sets of clothing, suitable linen, stockings, hats, and shoes, and a new set each year thereafter. Apprentices could not work during the night (between 9 pm and 6 am), and their working hours could not exceed 12 hours a day, excluding the time taken for breaks.[2] A grace period was provided to allow factories time to adjust, but all night-time working by apprentices was to be discontinued by June 1804.[1]

All apprentices were to be educated in reading, writing and arithmetic for the first four years of their apprenticeship. The Act specified that this should be done every working day within usual working hours but did not state how much time should be set aside for it. Educational classes should be held in a part of the mill or factory designed for the purpose. Every Sunday, for one hour, apprentices were to be taught the Christian religion; every other Sunday, divine service should be held in the factory, and every month the apprentices should visit a church. They should be prepared for confirmation in the Church of England between the ages of 14 and 18 and must be examined by a clergyman at least once a year. Male and female apprentices were to sleep separately and not more than two per bed.[2]

Local magistrates had to appoint two inspectors known as visitors to ensure that factories and mills were complying with the Act; one was to be a clergyman and the other a Justice of the Peace, neither to have any connection with the mill or factory. The visitors had the power to impose fines for non-compliance and the authority to visit at any time of the day to inspect the premises.[2]

The Act was to be displayed in two places in the factory. Owners who refused to comply with any part of the Act could be fined between £2 and £5.[2]

Cotton Mills and Factories Act 1819

The 1819 Cotton Mills and Factories Act (59 Geo. III c66) stated that no children under 9 were to be employed and that children aged 9–16 years were limited to 12 hours' work per day.[3] It applied to the cotton industry only, but covered all children, whether apprentices or not. It was seen through Parliament by Sir Robert Peel; it had its origins in a draft prepared by Robert Owen in 1815 but the Act that emerged in 1819 was much watered-down from Owen's draft. It was also effectively unenforceable; enforcement was left to local magistrates, but they could only inspect a mill if two witnesses had given sworn statements that the mill was breaking the Act.

Cotton Mills Regulation Act 1825

In 1825 John Cam Hobhouse introduced a Bill to allow magistrates to act on their own initiative, and to compel witnesses to attend hearings; noting that so far there had been only two prosecutions under the 1819 Act.[4] Opposing the Bill a millowner MP [lower-alpha 1] agreed that the 1819 Bill was widely evaded, but went on to remark that this put millowners at the mercy of millhands "The provisions of Sir Robert Peel's act had been evaded in many respects: and it was now in the power of the workmen to ruin many individuals, by enforcing the penalties for children working beyond the hours limited by that act" and that this showed to him that the best course of action was to repeal the 1819 Act.[4] On the other hand another millowner MP [lower-alpha 2] supported Hobhouse's Bill saying that he

agreed that, the bill was loudly called for, and, as the proprietor of a large manufactory, admitted that there was much that required remedy. He doubted whether shortening the hours of work would be injurious even to the interests of the manufacturers; as the children would be able, while they were employed, to pursue their occupation with greater vigour and activity. At the same time, there was nothing to warrant a comparison with the condition or the negroes in the West Indies.[4]

Hobhouse's Bill also sought to limit hours worked to eleven a day; the Act as passed (the Cotton Mills Regulation Act :6 Geo. IV., c. 63) improved the arrangements for enforcement, but kept a twelve-hour day Monday-Friday with a shorter day of nine hours on Saturday. The 1819 Act had specified that a mealbreak of an hour should be taken between 11 a.m. and 2 p.m. ; a subsequent Act (60 Geo. III., c. 5) allowing water-powered mills to exceed the specified hours in order to make up for lost time widened the limits to 11 a.m. to 4 p.m.; Hobhouse's Act of 1825 set the limits to 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. A parent's assertion of a child's age was sufficient, and relieved employers of any liability should the child in fact be younger. JPs who were millowners or the fathers or sons of millowners could not hear complaints under the Act.[1]

Act to Amend the Laws relating to the employment of Children in Cotton Mills & Manufactories 1829

In 1829, Parliament passed an 'Act to Amend the Laws relating to the employment of Children in Cotton Mills & Manufactories' which relaxed formal requirements for the service of legal documents on millowners (documents no longer had to specify all partners in the concern owning or running the mill; it would be adequate to identify the mill by the name by which it was generally known).[6] The Bill passed the Commons was subject to a minor textual amendment by the Lords (adding the words 'to include'[lower-alpha 3]) and then received the Royal Assent without the Commons first being made aware of (or agreeing to) the Lords' amendment.[7] To rectify this inadvertent breach of privilege,a further Act (making no other change to the Act already passed) was promptly passed on the last day of the Parliamentary session.[8][lower-alpha 4]

Labour in Cotton Mills Act 1831 (Hobhouse's Act)

An Act to repeal the Laws relating to Apprentices and other young Persons employed in Cotton Factories and in Cotton Mills, and to make further Provisions in lieu thereof (1 & 2 Will. IV c39)

- (Acts repealed were 59 Geo. III, c. 66; 60 Geo. III, c. 5; 6 Geo. IV, c. 63; 10 Geo. IV, c. 51; 10 Geo. IV, c. 63)

In 1831 Hobhouse introduced a further bill with - he told the Commons-[9] the support of the leading manufacturers who felt that "unless the House should step forward and interfere so as to put an end to the night-work in the small factories where it was practised, it would be impossible for the large and respectable factories which conformed to the existing law to compete with them." The Act repealed the previous Acts, and consolidated their provisions in a single Act, which also introduced further restrictions. Night working was forbidden for anyone under 21 and if a mill had been working at night the onus of proof was on the millowner (to show nobody under-age had been employed). The limitation of working hours to twelve now applied up to age eighteen. Complaints could only pursued if made within three weeks of the offence; on the other hand JPs who were the brothers of millowners were now also debarred from hearing Factory Act cases. Hobhouse's claim of general support was optimistic; the Bill originally covered all textile mills; the Act as passed again applied only to cotton mills.[1]

Labour of Children, etc., in Factories Act 1833 (Althorp's Act)

The Factory Act 1833 (3 & 4 Will. IV) c103 was an attempt to establish a regular working day in textile manufacture. The act had the following provisions:[1]

- Children under 9 could not be employed in textile manufacture (except in silk mills).

- Children under 18 must not work at night (i.e. after 8. 30 p.m. and before 5.30 a.m.)

- Children (ages 9–13) must not work more than 8 hours with an hour lunch break. (Employers could (and it was envisaged they would) operate a 'relay system' with two shifts of children between them covering the permitting working day; adult millworkers therefore being 'enabled' to work a 15-hour day)

- Children (ages 9–13) must have two hours of education per day.

- Children (ages 14–18) must not work more than 12 hours a day with an hour lunch break.

- Provided for routine inspections of factories and set up a Factory Inspectorate (subordinate to the Home Office) to carry out such inspections, with the right to demand entry and the authority to act as a magistrate. (Under previous Acts supervision had been by local 'visitors' (a Justice of the Peace, and a clergyman) and effectively discretionary). The inspectors were empowered to make and enforce rules and regulations on the detailed application of the Act, independent of the Home Secretary

- Millowners and their close relatives were no longer debarred (if JPs) from hearing cases brought under previous Acts, but were unlikely to be effectively supervised by their colleagues on the local bench or be zealous in supervising other millowners

Factories Act 1844 (Graham's factory act)

The Factories Act 1844 (citation 7 & 8 Vict c. 15) further reduced hours of work for children and applied the many provisions of the Factory Act of 1833 to women. The act applied to the textile industry and included the following provisions:[1]

- Children 9–13 years could work for 9 hours a day with a lunch break.

- Ages must be verified by surgeons.

- Women and young people now worked the same number of hours. They could work for no more than 12 hours a day during the week, including one and a half hours for meals, and 9 hours on Sundays. They must all take their meals at the same time and could not do so in the workroom

- Time-keeping to be by a public clock approved by an inspector

- Some classes of machinery: every fly-wheel directly connected with the steam engine or water-wheel or other mechanical power, whether in the engine-house or not, and every part of a steam engine and water-wheel, and every hoist or teagle, near to which children or young persons are liable to pass or be employed, and all parts of the mill-gearing (this included power shafts) in a factory were to be "securely fenced."

- Children and women were not to clean moving machinery.

- Accidental death must be reported to a surgeon and investigated; the result of the investigation to be reported to a Factory Inspector.

- Factory owners must wash factories with lime every fourteen months.

- Thorough records must be kept regarding the provisions of the Act and shown to the inspector on demand.

- An abstract of the amended Act must be hung up in the factory so as to be easily read, and show (amongst other things) names and addresses of the inspector and sub-inspector of the district, the certifying surgeon, the times for beginning and ending work, the amount of time and time of day for meals.

- Factory Inspectors no longer had the powers of JPs but (as before 1833) millowners, their fathers, brothers and sons were all debarred (if magistrates) from hearing Factory Act cases.

Factory Act 1847

After the collapse of the Peel administration which had resisted any reduction in the working day to less than 12 hours, a Whig administration under Lord John Russell came to power. The new Cabinet contained supporters and opponents of a ten-hour day and Lord John himself favoured an eleven-hour day. The Government therefore had no collective view on the matter; in the absence of Government opposition, the Ten Hour Bill (also known as the Ten Hour Act) was passed, becoming the Factories Act 1847 (citation 10 & 11 Vict c. 29). This law limited the work week in textile mills (and other textile industries except lace and silk production) for women and children under 18 years of age. Each work week contained 63 hours effective 1 July 1847 and was reduced to 58 hours effective 1 May 1848. In effect, this law limited the workday for all millhands to 10 hours.

This law was successfully passed due to the contributions of the Ten Hours Movement. This campaign was established during the 1830s and was responsible for voicing demands towards limiting the work week in textile mills. The leaders of the movement were Richard Oastler (who led the campaign outside Parliament), as well as John Fielden and Lord Ashley, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury (who led the campaign inside Parliament).

Factory Act 1850 (the 'Compromise' Act)

The Acts of 1844 and 1847 had reduced the hours per day which any woman or young person could work but not the hours of the day within which they could do that work (from 5:30 a.m. to 8:30 p.m.). Under the 1833 Act millowners (or some of them) had used a 'relay system' so that the mill could operate all the permitted hours without any protected person exceeding their permitted workday. The system was considered objectionable both because of the effect on the protected persons (who ended up working split shifts) and because an inspector (or other millowners) could relatively easily monitor the hours a mill ran; it was much more difficult if not impossible to check the hours worked by an individual (as an inspector observed "the lights in the window will discover the one but not the other")[1] Section 26 of the 1844 Act required that the hours of work of all protected persons " shall be reckoned from the time when any child or young person shall first begin to work in the morning in such factory." but nothing in it or in the 1847 Act clearly prohibited split shifts (although this had been Parliament's intention). The factory inspector for Scotland considered split shifts to be legal; the inspector for Bradford thought them illegal and his local magistrates agreed with him: in Manchester the inspector thought them illegal but the magistrates did not. In 1850 the Court of Exchequer held that the section was to be too weakly worded to make relay systems illegal.[10][lower-alpha 5] Lord Ashley sought to remedy this by a short declaratory Act restoring the status quo but felt it impossible to draft one which did not introduce fresh matter (which would remove the argument that there was no call for further debate). The Home Secretary Sir George Grey was originally noticeably ambivalent about Government support for Ashley's Bill: when Ashey reported his difficulties to the House of Commons, Grey announced an intention to move amendments in favour of a scheme (ostensibly suggested by a third party)[11] which established a 'normal day' for women and young persons by setting the times within which they could work so tightly that they were also the start and stop times if they were to work the maximum permitted hours per day. Grey's scheme increased the hours that could be worked per week, but Ashley (uncertain of the outcome of any attempt to re-enact a true Ten Hours Bill) decided to support it[12] and Grey's scheme was the basis for the 1850 Act (citation 13 & 14 Vict c. 54). The Short Time Committees had previously been adamant for an effective Ten-hour Bill; Ashley wrote to them,[12] noting that he acted in Parliament as their friend, not their delegate, explaining his reasons for accepting Grey's "compromise", and advising them to do so also. They duly did, significantly influenced by the thought that they could not afford to lose their friend in Parliament.[13] The key provisions of the 1850 Act were :[1]

- Women and young persons could only work from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. in the summer and 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. in the winter : since they were to be allowed 90 minutes total breaks during the day, the maximum hours worked per day increased to 10.5

- All work would end on Saturday at 2 p.m.

- The work week was extended from 58 hours to 60 hours.

Various public meetings in the textile districts subseqently passed motions regretting that the 58-hour week had not been more stoutly defended, with various stalwarts of the Ten-Hour Movement ( various Cobbetts and Fieldens (John Fielden now being dead) and Richard Oastler) offering their support and concurring with criticism of Ashley's actions, but nothing came of this: the Ten-Hour Movement had now effectively run its course.

Children (8-13) were not covered by this Act: it had been the deliberate intention of the 1833 Act that a mill might use two sets of children on a relay system and the obvious method of doing so did not require split shifts. A further Act of 1853 set similar limits on the hours within which children might work.

Factory Act 1856

In April 1855 a National Association of Factory Occupiers was formed "to watch over factory legislation with a view to prevent any increase of the present unfair and injudicious enactments". The 1844 Act had required that "mill gearing" - which included power shafts - should be securely fenced. Magistrates had taken inconsistent views as to whether this applied where the "mill gearing" was not readily accessible; in particular where power shafting ran horizontally well above head height. In 1856, the Court of Queen's Bench ruled that it did. In April, 1856, the National Association of Factory Occupiers succeeded in obtaining an Act reversing this decision: mill gearing needed secure fencing only of those parts with which women, young persons, and children were liable to come in contact. (The inspectors feared that the potential hazards in areas they did not normally access might be obvious to experienced men, but not be easily appreciated by women and children who were due the legislative protection the 1856 Act had removed, especially given the potential severe consequences of their inexperience. An MP speaking against the Bill was able to give multiple instances of accidents to protected persons resulting in death or loss of limbs - all caused by unguarded shafting with which they were supposedly not liable to come into contact - despite restricting himself to accidents in mills owned by Members of Parliament (so that he could be corrected by them if had misstated any facts).[14] (Dickens thereafter referred to the NAFO as the Association for Mangling Operatives)) For other parts of the mill gearing any dispute between the occupier and the inspector could be resolved by arbitration.[1] The arbitration was to be by a person skilled in making the machinery to be guarded; the inspectors however declined to submit safety concerns to arbitration by those "who look only to the construction and working of the machinery, which is their business,and not to the prevention of accidents, which is not their business" [1]

Factories Act Extension Act 1867

In virtually every debate on the various Factories Bills, opponents had thought it a nonsense to pass legislation for textile mills when the life of a mill child was much preferable to that of many other children: other industries were more tiring, more dangerous, more unhealthy, required longer working hours, involved more unpleasant working conditions, or (this being Victorian Britain) were more conducive to lax morals. This logic began to be applied in reverse once it became clear that the Ten Hours Act had had no obvious detrimental effect on the prosperity of the textile industry or on that of millworkers. Acts were passed bringing other textile trades within the scope of the Factories Act : bleaching and dyeworks (1860 - outdoor bleaching was excluded), lace work (1861), calendering (1863), finishing (1864).[1] In 1864 the Factories Extension Act was passed: this extended the Factories Act to cover a number of occupations (mostly non-textile): potteries (both heat and exposure to lead glazes were issues), lucifer match making ('phossie jaw') percussion cap and cartridge making, paper staining and fustian cutting.[1] In 1867 the Factories Act was extended to all establishments employing 50 or more workers by another Factories Act Extension Act. An Hours of Labour Regulation Act applied to 'workshops' (establishments employing less than 50 workers); it subjected these to requirements similar to those for 'factories' (but less onerous on a number of points e.g.: the hours within which the permitted hours might be worked were less restrictive, there was no requirement for certification of age) but was to be administered by local authorities, rather than the Factory Inspectorate.[1]

Factory and Workshop Act 1878

The Factory and Workshop Act 1878 (41 & 42 Vict. c. 16) brought all the previous Acts together in one consolidation.

- Now the Factory Code applied to all trades.

- No child anywhere under the age of 10 was to be employed.

- Compulsory education for children up to 10 years old.

- 10-14 year olds could only be employed for half days.

- Women were to work no more than 56 hours per week.

Factory Act 1891

Under the heading Conditions of Employment were two considerable additions to previous legislation: the first is the prohibition on employers to employ women within four weeks after confinement (childbirth); the second the raising the minimum age at which a child can be set to work from ten to eleven

Factory and Workshop Act 1895

The main article gives an overview of the state of Factory Act legislation in Edwardian Britain under The Factory and Workshop Acts 1878 to 1895 (the collective title of the Factory and Workshop Act 1878, the Factory and Workshop Act 1883, the Cotton Cloth Factories Act 1889, the Factory and Workshop Act 1891 and the Factory and Workshop Act 1895.)[15]

Factory and Workshop Act 1901

Minimum working age is raised to 12. The act also introduced legislation regarding education of children, meal times, and fire escapes.

Factories Act 1937

The 1937 Act (1 Edw. 8 & 1 Geo. 6 c.67) consolidated and amended the Factory and Workshop Acts from 1901 to 1929. It was introduced to the House of Commons by the Home Secretary, Sir John Simon, on 29 January 1937 and given Royal Assent on 30 July.[16][17]

Factories Act 1961

This Act consolidated the 1937 and 1959 Acts. As of 2008, the 1961 Act is substantially still in force, though workplace health and safety is principally governed by the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 and regulations made under it.

See also

- History of labour law in the United Kingdom

- UK labour law

- Mines Act of 1842

- Labour law

Notes

- ↑ George Philips; "the Member for Manchester" in fact MP for Wootton Bassett but his mill was in Salford and his business interests in Manchester[5]

- ↑ William Evans, MP for East Retford; he and his step-father had a variety of commercial interests in Derbyshire, including large water-powered mills at Darley Abbey on the Derbyshire Derwent

- ↑ to make a list indicative, rather than prescriptive ; a prudent amendment and not as trivial as it sounds. An Elizabethan parliament, feeling that nobody should take up a trade without having served an apprenticeship, passed a law to that effect. However since the law listed the trades then practised, without any preceding 'to include', the Act was subsequently held to cover only the trades it listed: trades which developed subsequently did not (legally) require an apprenticeship. Adam Smith in Wealth of Nations mocked the consequent illogicality.

- ↑ Unfortunately Hansard for 1829 is not accessible online; nor do Hutchins and Harrison appear to take any notice of these very minor bits of Factory Legislation. The necessary trawl through contemporary newspapers for 1829 throws up some interesting straws in the wind on the spirit of the age: two very young children accidentally locked in a Bolton cotton mill over the weekend (Lancaster Gazette, 13 June 1829) were there from 5 p.m. Saturday to 5 a.m. Monday , and a millowner working a nine-year-old more than twelve hours was fined £20 thanks to a prosecution at Stockport brought by a member of a society for enforcing the provisions of the 1825 Act ('Overworking Children in Cotton Factories' Manchester Times 25 April 1829). The same prosecutor had less success with a later prosecution at Macclesfield ('Overworking Children and Paying in Goods' Manchester Times 15 August 1829) (but if laws are passed to change behaviours not to punish wrongdoersthe Truck Act action was successful : the millowner having been found not guilty (on a defence that his tokens could be exchanged for legal tender at face value at the company shop) promised to take the bench's advice and to henceforth pay in coin of the realm )

- ↑ prompting Punch to suggest it would be more appropriate to refer to the Unsatis-Factory Act

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 Hutchins & Harrison (1911).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Statutes at Large: Statutes of the United Kingdom, 1801–1806. 1822.

- ↑ Early factory legislation. Parliament.uk. Accessed 2 September 2011.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Cotton Mills Regulation Bill". Hansard House of Commons Debates 13 (cc643-9). 16 May 1825. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ↑ "Member Biographies: George Philips". The History of Parliament. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ↑ "Employment of Children". Manchester Times. 30 May 1829. p. 263.

- ↑ "Imperial Parliament". Morning Post (23 June 1829).

- ↑ "Imperial Parliament (subheading: Legislative Mistake)". Hull Packet. 30 June 1829.

- ↑ "Appentices in Factories". Hansard House of Commons Debates 2 (cc584-6). 15 February 1831. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ↑ "Factories". Hansard House of Commons Debates 109 (cc883-933). 14 March 1850. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ↑ "A Manufacturer" (27 April 1850). "The Ten Hours Act". Leeds Mercury. giving text of a letter to the Times - John Walter, both the editor of the Times and a Government MP was said by contemporaries to have discussed such a scheme before the date the letter was supposedly written

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 letter Lord Ashley , dated 7 May , to "The Short Time Committees of Lancashire and Yorkshire""Lord Ashley and the Factory Act". London Standard. 9 May 1850.

- ↑ "The Factory Question". Preston Chronicle and Lancashire Advertiser. 18 May 1850.

- ↑ "FACTORIES BILL". Hansard House of Commons Debates 141 (cc351-77). 2 April 1856. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ↑ The Short Titles Act 1896, section 2(1) and the second schedule

- ↑ "House of Commons Hansard; vol 319 c1199". Hansard. Parliament of the United Kingdom. 29 January 1937. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ↑ Factories Act 1937 (PDF). London: His Majesty's stationery Office. 30 July 1937. ISBN 0-10-549690-1. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- Hutchins, B. L.; Harrison, A. (1911). A History of Factory Legislation. P. S. King & Son.

- Encyclopedia of British History

- W.R. Cornish and G. de N. Clark. Law and Society in England 1750-1950. (Available online here).

External links

- Aspects of the Industrial Revolution in Britain : Working Conditions and Government Regulation - a selection of primary documents

- The 1802 Health and Morals of Apprentices Act

- Timeline of Factory Legislation in Britain

- Ten Hours Act

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||