Facing colour

A facing colour is a common European uniform military tailoring technique where the inside lining of a standard military jacket, coat or tunic visible to the observer, is of a different colour to that of the garment itself.[1][2] The jacket lining evolved to be of different coloured material, then of specific hues. Accordingly when the material was turned back on itself: the cuffs, lapels and tails of the jacket exposed the contrasting colours of the lining or facings, enabling ready visual distinction of different units: regiments, divisions or battalions each with their own specific and prominent colours. While a popular practice in 18th century armies, the use of facings was especially observed and elaborated on during the Napoleonic Wars.[2][3][4]

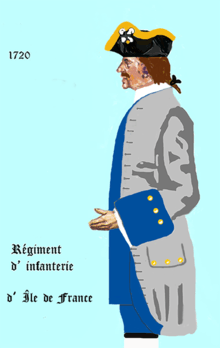

France

During the Ancien Régime, there were many different facing colours (notably various shades of blue, red, yellow, green and black) on the standard grey-white uniforms of the French line infantry.[5] Examples included blue for the Régiment du Languedoc, red for the Régiment du Béarn etc. The initiative in fixing or changing facing colours was largely left to individual colonels, who in effect had ownership of their regiments. This tendency towards variegated facings reached its height in the "Dress Regulation Facings for the Army" of 31 May 1776 when unusual shades such as silver-grey, aurore and "red speckled with white" were added to the by-then white uniforms of the French infantry.[6] In 1791 an attempt was made to rationalize facings by giving groupings of up to six regiments a single colour, relying on secondary features such as piping or button patterns to distinguish separate units.[7]

The rise of mass conscript armies during and following the Napoleonic Wars led to increasing standardisation of facing colours, for reasons both of economy and supply efficiency. Thus, for example, the French line fusiliers and grenadiers of the early 19th century had red facings, with only numbers to distinguish one regiment from another. The voltigeurs had yellow or/and green facings. From 1854 on red facings became universal for all of the line infantry who made up the bulk of the French metropolitan Army, although the Chasseurs, who constituted a separate branch, retained yellow facings as a special distinction.

Great Britain

The standard red jacket ("redcoat") worn by British infantry soldiers made it difficult to distinguish between units when engaged in battle. The use of Colours assisted soldiers in rallying on a common point, and each Regiment had a flag, or Colour, in a specific shade so as to be easily distinguished. The lining of uniform jackets came to be made from material of the same regimental colours, and when the material was turned back, in the cuffs, lapels and tails of the jacket, the lining, or "facing" was exposed. Facings came to be used by most European armies during the late 17th and early 18th century periods.

The tradition of associating particular colours with specific Regiments continued into the 20th century, even when the use of red tunics ceased in favor of khaki. These facings remained a part of ceremonial, and the practice was adopted by Commonwealth military units that adopted dress distinctions from affiliated units of the British Army.

In 1881 an attempt was made as an economy measure to standardise facing colours for British infantry regiments (other than the 4 rifle regiments who wore dark green uniforms) according to the following system:

- Guards and "Royal" Regiments (i.e. those with "Royal", "King's", "Queen's" or Prince Albert's name in the title) - Dark Blue.

- English & Welsh Regiments - White.

- Scots Regiments - Yellow.

- Irish Regiments - Green (In fact this meant only the Connaught Rangers. All other Irish Regiments were "Royal" and so had dark blue facings).

While this standardisation made the manufacturing and replacement of uniforms simpler, it proved unpopular amongst the army at large. Some regiments (e.g. The Buffs and Green Howards) derived their names or nicknames from the colour of their facings and the Duke of Wellington's Regiment (who had red facings) lost their claim to be the only truly red coated regiment in the British Army.

So widespread was opposition to the order, and so frequent the requests for special exceptions to be made, that the scheme in its original form was finally dropped and the historic colours were re-instated in a number of regiments, until full dress for the Army as a whole finally vanished with the coming of war in 1914. While many regiments did continue with their new 1881 facings, instances where reversion to traditional colours was approved included the Northumberland Fusiliers (white to Gosling green), the Manchester Regiment (white to Lincoln green), the Norfolk Regiment (white to yellow), the Essex Regiment (white to 'Pompadour Purple'), the Devonshire Regiment (white to Lincoln green), the Highland Light Infantry (yellow to buff), the Seaforth Highlanders (yellow to buff), the Prince of Wales's Own Yorkshire Regiment (white to grass green), the Duke of Wellington's Regiment (white to scarlet), the Duke of Edinburgh's Wiltshire Regiment (white to buff), the Suffolk Regiment (white to yellow), the Durham Light Infantry (white to dark green) and the Buffs (white to buff).[8] Even after World War I this tendency to revert to historic facings continued, although by that time the scarlet uniforms were normally worn only by regimental bands and by officers in mess and levee dress. As examples the Norfolk Regiment regained its former yellow facings in 1925 and the North Staffordshire Regiment its pre-1881 black facings in 1937.[9]

Other armies

The practice of using different facing colours to distinguish individual regiments had been widespread in European armies in the 18th century when such decisions were largely left to commanding officers and uniforms were made by individual contractors rather than in centralized government clothing factories.

By the second half of the nineteenth century, the Dutch, Spanish, Swiss, Belgian, Japanese, Portuguese, Italian, Romanian, Swedish, Chilean, Mexican, Greek and Turkish armies had come to follow French standardised arrangements, although some variety might still be ensured by the existence of different types of infantry (grenadiers, fusiliers, rifles, light infantry etc.) within a particular army, each with its own uniform and facings. As a general rule cavalry tended to be more variegated and it was not uncommon for each mounted regiment to retain its own facings colours up to 1914.[10] Artillery, engineers and support corps normally had a single brand colour, although exceptionally each regiment of Swedish artillery had its own facing colour until 1910

The United States regular army after the American Civil War adopted a universal dark and light blue uniform under which each regiment was distinguished only by numbers and other insignia, plus branch colors. The latter were yellow for Cavalry, red for Artillery and white (later light blue) for infantry. Combinations of colors such as scarlet piped with white for Engineers, orange piped with white for the Signal Corps and black piped with scarlet for Ordnance personnel gave wide scope for adding distinctive branch facings as the Army became more technical and diverse.[11] This system continued in general use until blue uniforms ceased to be general issue in 1917, and survives in a limited form in modern blue mess and dress uniforms.

Notable exceptions to such standardisation within branches were the British Army (as noted above) and the Austro-Hungarian one. As late as World War I the latter employed 28 different colours, including 10 different shades of red, for its infantry facings.[12]

In the very large Imperial German and Russian armies infantry, facing colours were often allocated according to the position that a particular regiment held in the order of battle - that is within a brigade, division or corps. As an example, amongst the Russian line infantry, the two brigades within each division were distinguished by red or blue shoulder straps; while the four regiments within each division wore red, blue, white or green collar patches and cap bands respectively.[13]

References

- ↑ Otto Von Pivka, Michael Roffe, Richard Hook, G. A. (Gerry A.) Embleton, Bryan Fosten, Napoleon's German allies, Osprey Publishing: 1980, ISBN 0-85045-373-9, 48 pages

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 René Chartrand, William Younghusband, Bill Younghusband, Gerry Embleton Spanish Army of the Napoleonic wars, Osprey Publishing: 1998, ISBN 1-85532-763-5, 48 pages

- ↑ Hugh Chisholm, The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information Volume 27, "Uniforms", At the University press: 1911, pp: 584-593

- ↑ http://www.napoleonguide.com/infantry_austface.™

- ↑ Liliane et Fred Funcken, pages 48-90 volume 1 "L'Uniforme et les Armes des Soldats de la Guerre en Dentelle, ISBN 2-203-14315-0

- ↑ Rene Chartrand, page 21 "The French Army in the American War of Independence', ISBN 1-85532-167-X

- ↑ Liliane et Fred Funcken, pages 82-83 volume 1 "L'Uniforme et les Armes des Soldats de la Guerre en Dentelle, ISBN 2-203-14315-0

- ↑ R.M. Barnes, "A History of the Regiments and Uniforms of the British Army"

- ↑ W.Y. Carmen, pages 41 & 84 "Richard Simkin's Uniforms of the British Army - the Infantry Regiments", ISBN 0-86350-031-5

- ↑ A.E. Haswell Miller, "Vanished Armies", ISBN 978 0 74780 739 1

- ↑ Regulations and Notes for the Uniform of the Army of the United States 1902 and 1912

- ↑ James Lucas, "Fighting Troops of the Austro-Hungarian Army 1868-1914, ISBN 0-87052-362-7

- ↑ Richard Knotel, page 375 Uniforms of the World, ISBN 0-684-16304-7