Externsteine

The Externsteine [ˈɛkstɐnʃtaɪnə] is a distinctive sandstone rock formation located in the Teutoburg Forest, near the town of Horn-Bad Meinberg in the Lippe district of the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia. The formation is a tor consisting of several tall, narrow columns of rock which rise abruptly from the surrounding wooded hills.

In a popular tradition going back to an idea proposed to Hermann Hamelmann in 1564, the Externsteine are identified as a sacred site of the pagan Saxons, and the location of the Irminsul idol destroyed by Charlemagne; there is however no archaeological evidence that would confirm the site's use during the relevant period. The stones were used as the site of a hermitage from the early 9th century, and by at least the high medieval period were the site of a Christian chapel. The Externsteine relief is a medieval depiction of the Descent from the Cross.

Name

The etymology of the name Extern- is unclear (-steine meaning "stones"). The Latinized spelling with x is first recorded in the 16th century, but became common only in the late 19th century.

The oldest recorded forms of the name read Agistersten and Eggesterenstein, both dated 1093. Other forms of the name include Egesterenstein (12th c.), Egestersteyn (1366), Egersteyne (1369), Egestersten (1385), Egesternsteyn (15th c.), Eygesternsteyn (151), Externsteine (1533), Egesterennstein (1583), Agisterstein (1592).[1]

Hamelmann (1564) gives the Latinized name rupes picarum ("rock of the magpies"), associating the name with Westphalian word Eckster "magpie" (Standard German Elster). Eckster "magpie" is argued to be the actual etymology of the name by Schröder (1964), who also connects other Westphalian toponyms Externbrock, Externmühle, Exter, Extern, Exten an der Exter. Other scholars identify the association with magpies as folk etymology; Plassmann (1961) connects the name with a giant Ecke or Ekka of the Eckenlied, a medieval poem of the Theoderic cycle. [2] Bahlow (1962, 1965) connects the name to the hydronym Exter.[3]

Geology

The Externsteine are located in the Teutoburger Wald and are a natural outcropping of five sandstone pillars, the tallest of which is 37.5 m (123 ft) high and form a wall of several hundred metres in length, in a region that is otherwise largely devoid of rocks. The pillars have been modified and decorated by humans over the centuries.

The geological formation consists of a hard, erosion-resistant sandstone, laid down during the early Cretaceous era about 120 million years ago, near the edge of a large shallow sea that covered large parts of Northern Europe at the time. About 70 million years ago, these originally horizontal layers were folded to an almost vertical position; this was followed by various forms of weathering.

History

Prehistory

Archaeological excavations yielded some Upper Paleolithic stone tools dating to before about 10,000 BC.[4]

The site is associated with archaeoastronomical speculation; a circular hole above the "altar stone" has been identified in this context as facing the direction of sunrise at the time of summer solstice.[5]

No archaeological evidence has been found that would substantiate use of the site between the end of the Upper Paleolithic and the Carolingian period (9th century). In the 1990s, artefacts found in the excavation conducted by Julius Andree in 1934/35 were analyzed. Attribution of objects found was either to the Mesolithic Ahrensburg culture or to the medieval period, with evidence of occupation in the Bronze or Iron Age conspicuously absent. All the ceramic and metal items were younger than the Carolingian period, some stone artefacts were attributed to the Ahrensburg culture.[6]

Middle Ages

Archaeological excavations at the site produced evidence for occupation throughout the late 10th to the 19th centuries. The first mention of the stones is in a document dated to the 12th or 13th century, the copy of a 1093 record of the purchase of the site by Bishop of Paderborn from its earlier owner, the Abdinghof monastery in Paderborn. Traces of the presence of hermits or monks may suggest use of the site as a Christian sanctuary from the early 9th century.[7]

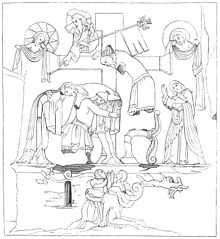

The most striking evidence of medieval use of the site as a sanctuary is the monumental Externsteine relief, showing a Descent from the Cross scene. Its date is the subject of debate among art historians, formerly widely accepted as of Carolingian origin (9th century), scholarly consensus has placed it in the 12th century since the 1950s.[8] Even assuming a high medieval date, the relief represents the oldest monumental relief worked into a natural rock face found north of the Alps.

Other modifications of the stones, the excavation of grottos for habitation, as tombs or as chapels, cannot be dated archaeologically but is also consistent with medieval presence of hermit monks. An inscription in the main grotto or "lower chapel" is dated internally to the year 1115, but its authenticity has been doubted, and it is now mostly considered to date to the later medieval period. Direct records of mass celebrated at the site date from the 14th century onwards.[9]

Early modern period

The site was within the county of Lippe, formerly a county within the Duchy of Saxony, which gained imperial immediacy by 1413, throughout the Early modern period and (from 1789 elevated to Principality) until 1918. After the Reformation, possession of the site passed from the bishopric to the count.

The original testimony associating the Externsteine with Saxon pagan worship is due to Hermann Hamelmann, who in his Delineatio Oppidorum Westfaliae (1564) claimed to take the information from older authorities (which cannot now be recovered or identified),

- Horne ... ex vicina rupe picarum, antiquo monumento, cuius veteres scriptores mentionem fecerunt, claret. Legi aliquando, quod ex rupe illa picarum, idolo gentilitio, fecerit Carolus magnus altare sacratum et ornatum effigiebus apostolorum

- "Horn is famous for the "rock of the magpies", an ancient monument mentioned by older writers. I have read that Charlemagne from this rock of the magpies, then a pagan idol, made a consecrated altar decorated with images of the apostles."

The same passage is also the source of the association of the site's name with the word for "magpie" (dialectal Eckster).[10]

In 1659, Ferdinando II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany offered to buy the site from Herman Adolph, Count of Lippe for the considerable sum of 60,000 crowns and 3,000 thaler, but the transaction was not completed. A few years later, Herman Adolph constructed a fortified hunting lodge or castle close to the stones. The structure was rarely used, and fell into dilapidation in the 18th century. In 1810, it was torn down at the request of countess Pauline.[9]

Modern history

_b_381.jpg)

The old road running across the stones (now a footpath) was expanded and paved in 1813. The unstable Wackelstein was secured with iron hooks.

The Wiembecke stream flowing past the stones was dammed to form an artificial pond in 1836. The pond was drained for the excavations of 1934/5, and restored after 1945.

The period of Romantic nationalism of the 1860s to 1870s inspired a large number of publications speculating about the ancient history of the site. Many of these were contributed by local amateur historians and published in the Zeitschrift für vaterländische Geschichte und Althertumskunde Westfalens. The contributions by Wilhelm Engelbert Giefers (1817–1880) were reprinted as a short monograph in 1867.[11] Of special interest are the contributions by local amateur historian Gotthilf August Benjamin Schierenberg (1808–1894), who seems to have been the first to identify the "pagan idol" mentioned by Hamelmann with the Saxon Irminsul. When Wilhelm Teudt came to re-examine the question beginning in 1925, he could refer to a total number of more than 40 publications, including eleven substantial monographs, most of which he considered outdated.[12]

The first archaeological excavations were performed in 1881 and 1888, with limited results. From 1912 to 1935, a tramway ran along the Externsteine road, operated by Paderborner Elektrizitätswerke und Straßenbahn AG (PESAG). A stop was located right next to the stones.

With the introduction of a road numbering system in 1932, the road became part of Fernverkehrsstraße Nr. 1 (Aachen–Königsberg); the course of the road was relocated to the south-east in order to avoid the stones in 1936 (the present-day B1).

In 1926, the Externsteine were declared "one of the oldest and most important nature reserves in Lippe" and were placed under protection.[13] Today it is approximately 27 acres (0.11 km2; 0.042 sq mi), and forms part of the ‘Teutoburg Forest’ nature reserve, Externsteine.[14]

Wilhelm Teudt was particularly interested in the Externsteine, which he suggested was the location of a central Saxon shrine, the location of Irminsul and an ancient sun observatory. Since the mid-1920s he had popularized them by calling them the "Germanic Stonehenge".[6]:69 Teudt popularized the identification of the site as that of the Saxon Irminsul destroyed by Charlemagne. [15] In 1932, the area was excavated (for the third time) by August Stieren and no "cultural remains" were discovered.[6]:69

During the period of Nazi rule, the Externsteine became a focus of nationalistic propaganda. In 1933, the "Externsteine Foundation" was established and Heinrich Himmler became its president. Interest in the location was furthered by the Ahnenerbe division within the SS, who studied the stones for their value to Germanic folklore and history.[16]

After the Nazis came to power, Teudt was put in charge of additional excavations at the site and appointed Julius Andree to head the work done there by the Reichsarbeitsdienst in 1934/35.[17] Teudt thought that the Externsteine had served as an observatory until its destruction by Charlemagne. He initiated the demolishing of touristical infrastructure (tramway, hotels) and the creation of a "sacred grove" or Heiligtum nearby. The SS used Serbian prisoners of war for the project.[6]:70

Since the 1950s, the Externsteine were developed into a popular tourist attraction. The section of the tramway line connecting to the Externsteine was closed in 1953. In 1958, visitor numbers were around 224,000 people annually.[18]

Today, between a half to one million people annually visit the stones, making the Externsteine one of the most frequently visited nature reserves in Westphalia. The also site remains to be of interest to various Neo-Pagas and nationalist movements.

Because of its reputation as "pagan sacred site" in popular cultre, there have often been private gatherings or celebrations on the day of summer solstice and Walpurgis Night. The trend had been visible since the 1980s, but the growing number of visitors came to be seen as a problem in the late 2000s, with more than 3,500 on the site. The municipalities of the Lippe (Landesverband Lippe) reacted by prohibiting camping, alcohol consumption and open fires on the site in 2010 and closed the parking at the site. A spokesman emphasized that the decision was not directed against "esotericists, druids and dowsers", but against large-scale parties of binge-drinkers.[19]

References

- ↑ H. Beck, J. Udolph, "Externsteine: Namenkundliches" in Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde vol. 8 (1994), 46–48.

- ↑ Plassmann connects the suffix -istra with the lexeme agis "serpent", connecting the legend of Theoderic slaying the giant Ekka with the ancient Drachenkampf myth of a hero killing a serpent demon.

- ↑ Plassmann (1961), Bahlow (1962, 1965) and Schröder, Deutsche Namenskunde 2nd ed. (1964) cited after H. Beck, J. Udolph, "Externsteine: Namenkundliches" in Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde vol. 8 (1994), 46–48.

- ↑ "Mythology: Externsteine". germany-tourism.de. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ↑ Wolfhard Schlosser / Jan Cierny. Sterne und Steine. Eine praktische Astronomie der Vorzeit. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. Darmstadt. 1996. p.93-95.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Halle, Uta (2013), "Wichtige Ausgrabungen der NS-Zeit", in Focke-Museum, Bremen, Graben für Germanien - Archäologie unterm Hakenkreuz, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, pp. 65–73, ISBN 978-3-534-25919-9

- ↑ Walther Matthes. Corvey und die Externsteine. Schicksal eines vorchristlichen Heiligtums in karolingischer Zeit. Urachhaus. Stuttgart. 1982. pp. 172ff.

- ↑ Otto Schmitt: "Zur Datierung des Externsteinreliefs". In: Oswald Goetz (ed.): Beiträge für Georg Swarzenski zum 11. Januar 1951. Mann, Berlin 1951, S. 26–38; Fritz Saxl: "English Sculptures of the 12th Century." ed. Hanns Swarzenski. Faber & Faber, London 1954; Otto Gaul: "Neue Forschungen zum Problem der Externsteine". In: Westfalen. 32 (1955), S. 141–164. dissenting view: Walther Matthes / Rolf Speckner: Das Relief an den Externsteinen. Ein karolingisches Kunstwerk und sein spiritueller Hintergrund. 3rd ed., Ostfildern vor Stuttgart, 1997.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Externsteine: Historische Nachrichten und Besitzverhältnisse" in Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde vol. 8 (1994), 40–42.

- ↑ cited after the 2013 reprint of Wilhelm Teudt's Germanische Heiligtümer of 1931 (p. 71).

- ↑ W. E. Giefers, Die Externsteine im Fürstenthum Lippe, Regensberg, 1867.

- ↑ Teudt, Germanische Heiligtümer (1931), p. 25 (cited after the 2013 reprint). "Die Detmolder Landesbibliothek enthält eine aus etwa 40 Nummern bestehende Literatur über die Externsteine bei Horn im Teutoburger Walde, von denen 11 als eingehendere Monographien (bis zu einem Umfang von 200 Seiten) angesehen werden können. Diese stammen sämtlich aus dem vorigen Jahrhunderrt, die letzte von Kisa 1895. Uns, die wir eine wesentlich erweiterte Anschauung über die altgermanische Kultur haben, mutet die ganze Behandlungsweise des Gegenstandes als veraltet an, abgesehen von Kisa."

- ↑ bezreg-detmold.nrw.de - "Nature Extersteine"

- ↑ reserve LIP-007 "Externsteine"

- ↑ Germanische Heiligtümer. Beiträge zur Aufdeckung der Vorgeschichte, ausgehend von den Externsteinen, den Lippequellen und der Teutoburg (1931). chapter 3, "Irminsul und Felsenbild". Teudt cites the support of Hans Schmidt, Vaterländische Blätter, Detmold, January 1930, (Das Gesamtheiligtum Irminsul ist identisch mit den Externsteinen "The entirety of the sanctuary Irminsul is identical with the Externsteine" and mentions the priority of Grupen and Schierenberg (p. 69, cited after the 2013 reprint).

- ↑ Uta Halle. 'Die Externsteine sind bis auf weiteres germanisch!'. Bielefeld 2002.

- ↑ Mahsarski, Dirk (2013), ""Schwarmgeister und Phantasten" - die völkische Laienforschung", in Focke-Museum, Bremen, Graben für Germanien - Archäologie unterm Hakenkreuz, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, pp. 50–56, ISBN 978-3-534-25919-9

- ↑ Fritz Runge: The nature reserves of the former administrative district of Westphalia and Osnabrück. Aschendorff. Munster. 3rd ed. 1978. 143-144. ISBN 3-402-04382-3

- ↑ Kein "Koma-Saufen" mehr an Externsteinen. In: Mindener Tageblatt. 10. April 2010. "Stephan Radeck von der Denkmalsstiftung des Landesverbands Lippe [...] Seit rund 25 Jahren habe es an diesen Terminen friedliche Feiern mit einigen Dutzend Teilnehmern an den Externsteinen gegeben, sagte Radeck. In den vergangenen Jahren seien es aber bis zu 3500 gewesen. Hunderte Zelte seien im Naturschutzgebiet aufgebaut worden. Die Behörden haben das nicht genehmigt, aber toleriert. Zelte, Alkohol und Lagerfeuer werden verboten. 'Wir haben nichts gegen Esoteriker, Druiden und Wünschelrutengänger. Sie können hier tanzen und musizieren.' Das 'schillernde Publikum' gehöre zu der Kultstätte. 'Aber ganze Horden mit Alkoholvorräten in Bollerwagen werden wir nicht zulassen.'"

Bibliography

- Becher, Matthias (2003). Charlemagne. trans. David S. Bachrach. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09796-4.

- Runge, Fritz (1 January 1973). Westfälische Bibliographie (in German). Westfälisch-Niederrheinisches Institut für Zeitungsforschung Stadt- und Landesbibliothek, Dortmund. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- Hans Schmidt: Externstein-Führer. Hermann Bösmann GmbH Verlag, Detmold 1973.(German)

- Цибулькін В. В., Лисюк І. П. СС-Аненербе: розсекречені файли. - Київ-Хмельницький: ВАТ "Видавництво "Поділля", 2010. - С. 266-268

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Externsteine. |