Exact sequence

An exact sequence is a concept in mathematics, especially in ring and module theory, homological algebra, as well as in differential geometry and group theory. An exact sequence is a sequence, either finite or infinite, of objects and morphisms between them such that the image of one morphism equals the kernel of the next.

Definition

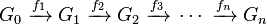

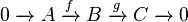

In the context of group theory, a sequence

of groups and group homomorphisms is called exact if the image of each homomorphism is equal to the kernel of the next:

Note that the sequence of groups and homomorphisms may be either finite or infinite.

A similar definition can be made for other algebraic structures. For example, one could have an exact sequence of vector spaces and linear maps, or of modules and module homomorphisms. More generally, the notion of an exact sequence makes sense in any category with kernels and cokernels.

Special cases

To make sense of the definition, it is helpful to consider what it means in relatively simple cases where the sequence is finite and begins or ends with 0.

- The sequence 0 → A → B is exact at A if and only if the map from A to B has kernel {0}, i.e. if and only if that map is a monomorphism (one-to-one).

- Dually, the sequence B → C → 0 is exact at C if and only if the image of the map from B to C is all of C, i.e. if and only if that map is an epimorphism (onto).

- A consequence of these last two facts is that the sequence 0 → X → Y → 0 is exact if and only if the map from X to Y is an isomorphism.

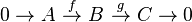

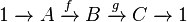

Important are short exact sequences, which are exact sequences of the form

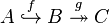

As established above, for any such short exact sequence, f is a monomorphism and g is an epimorphism. Furthermore, the image of f is equal to the kernel of g. It is helpful to think of A as a subobject of B with f being the embedding of A into B, and of C as the corresponding factor object (aka quotient) B/A, with the map g being the natural projection from B to B/A (whose kernel is exactly A).

Short exact sequence

The most common type of exact sequence is the short exact sequence. This is an exact sequence of the form

where ƒ is a monomorphism and g is an epimorphism. In this case, A is a subobject of B, and the corresponding quotient is isomorphic to C:

(where f(A) = im(f)).

A short exact sequence of abelian groups may also be written as an exact sequence with five terms:

where 0 represents the zero object, such as the trivial group or a zero-dimensional vector space. The placement of the 0's forces ƒ to be a monomorphism and g to be an epimorphism (see below).

If instead the objects are groups not known to be abelian, then multiplicative rather than additive notation is traditional, and the identity element—as well as the trivial group—is often written as "1" instead of "0". So in that case a short exact sequence would be written as follows:

Examples

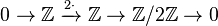

Consider the following sequence of abelian groups:

The first operation forms an element in the set of integers, Z, using multiplication by 2 on an element from Z i.e. j = 2i. The second operation forms an element in the quotient space, j = i mod 2. Here the hook arrow  indicates that the map 2⋅ from Z to Z is a monomorphism, and the two-headed arrow

indicates that the map 2⋅ from Z to Z is a monomorphism, and the two-headed arrow  indicates an epimorphism (the map mod 2). This is an exact sequence because the image 2Z of the monomorphism is the kernel of the epimorphism. Essentially "the same" sequence can also be written as

indicates an epimorphism (the map mod 2). This is an exact sequence because the image 2Z of the monomorphism is the kernel of the epimorphism. Essentially "the same" sequence can also be written as

In this case the monomorphim is  and although it looks like an identity function, it is not onto (i.e. not an epimorphism) because the odd numbers don't belong to

and although it looks like an identity function, it is not onto (i.e. not an epimorphism) because the odd numbers don't belong to  . The image of

. The image of  through this monomorphism is however exactly the same subset of

through this monomorphism is however exactly the same subset of  as the image of

as the image of  through

through  used in the previous sequence. This latter sequence does differ in the concrete nature of its first object from the previous one as

used in the previous sequence. This latter sequence does differ in the concrete nature of its first object from the previous one as  is not the same set as

is not the same set as  even though the two are isomorphic as groups.

even though the two are isomorphic as groups.

The first sequence may also be written without using special symbols for monomorphism and epimorphism:

Here 0 denotes the trivial abelian group with a single element, the map from Z to Z is multiplication by 2, and the map from Z to the factor group Z/2Z is given by reducing integers modulo 2. This is indeed an exact sequence:

- the image of the map 0→Z is {0}, and the kernel of multiplication by 2 is also {0}, so the sequence is exact at the first Z.

- the image of multiplication by 2 is 2Z, and the kernel of reducing modulo 2 is also 2Z, so the sequence is exact at the second Z.

- the image of reducing modulo 2 is all of Z/2Z, and the kernel of the zero map is also all of Z/2Z, so the sequence is exact at the position Z/2Z

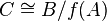

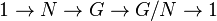

The first and third sequences are somewhat of a special case owing to the infinite nature of  . It is not possible for a finite group to be mapped by inclusion (i.e. by a monomorphism) as a proper subgroup of itself. Instead the sequence that emerges from the first isomorphism theorem is

. It is not possible for a finite group to be mapped by inclusion (i.e. by a monomorphism) as a proper subgroup of itself. Instead the sequence that emerges from the first isomorphism theorem is

As a more concrete example of an exact sequence on finite groups:

where  is the cyclic group of order

is the cyclic group of order  and

and  is the dihedral group of order

is the dihedral group of order  , which is a non-abelian group.

, which is a non-abelian group.

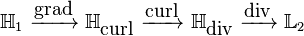

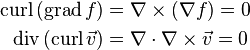

Another example, from differential geometry, especially relevant for work on the Maxwell equations:

based on the fact that on properly defined Hilbert spaces,

in addition, curl-free vector fields can always be written as a gradient of a scalar function (as soon as the space is assumed to be simply connected, see Note 1 below), and that a divergenceless field can be written as a curl of another field.[1]

Note 1: this example makes use of the fact that 3-dimensional space is topologically trivial.

Note 2:  and

and  are the domains for the curl and div operators respectively.

are the domains for the curl and div operators respectively.

Facts

The splitting lemma states that if the above short exact sequence admits a morphism t: B → A such that t o f is the identity on A or a morphism u: C → B such that g o u is the identity on C, then B is a twisted direct sum of A and C. (For groups, a twisted direct sum is a semidirect product; in an abelian category, every twisted direct sum is an ordinary direct sum.) In this case, we say that the short exact sequence splits.

The snake lemma shows how a commutative diagram with two exact rows gives rise to a longer exact sequence. The nine lemma is a special case.

The five lemma gives conditions under which the middle map in a commutative diagram with exact rows of length 5 is an isomorphism; the short five lemma is a special case thereof applying to short exact sequences.

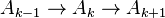

The importance of short exact sequences is underlined by the fact that every exact sequence results from "weaving together" several overlapping short exact sequences. Consider for instance the exact sequence

which implies that there exist objects Ck in the category such that

.

.

Suppose in addition that the cokernel of each morphism exists, and is isomorphic to the image of the next morphism in the sequence:

(This is true for a number of interesting categories, including any abelian category such as the abelian groups; but it is not true for all categories that allow exact sequences, and in particular is not true for the category of groups, in which coker(f): G → H is not H/im(f) but  , the quotient of H by the conjugate closure of im(f).) Then we obtain a commutative diagram in which all the diagonals are short exact sequences:

, the quotient of H by the conjugate closure of im(f).) Then we obtain a commutative diagram in which all the diagonals are short exact sequences:

Note that the only portion of this diagram that depends on the cokernel condition is the object C7 and the final pair of morphisms A6 → C7 → 0. If there exists any object  and morphism

and morphism  such that

such that  is exact, then the exactness of

is exact, then the exactness of  is ensured. Again taking the example of the category of groups, the fact that im(f) is the kernel of some homomorphism on H implies that it is a normal subgroup, which coincides with its conjugate closure; thus coker(f) is isomorphic to the image H/im(f) of the next morphism.

is ensured. Again taking the example of the category of groups, the fact that im(f) is the kernel of some homomorphism on H implies that it is a normal subgroup, which coincides with its conjugate closure; thus coker(f) is isomorphic to the image H/im(f) of the next morphism.

Conversely, given any list of overlapping short exact sequences, their middle terms form an exact sequence in the same manner.

Applications of exact sequences

In the theory of abelian categories, short exact sequences are often used as a convenient language to talk about sub- and factor objects.

The extension problem is essentially the question "Given the end terms A and C of a short exact sequence, what possibilities exist for the middle term B?" In the category of groups, this is equivalent to the question, what groups B have A as a normal subgroup and C as the corresponding factor group? This problem is important in the classification of groups. See also Outer automorphism group.

Notice that in an exact sequence, the composition fi+1 o fi maps Ai to 0 in Ai+2, so every exact sequence is a chain complex. Furthermore, only fi-images of elements of Ai are mapped to 0 by fi+1, so the homology of this chain complex is trivial. More succinctly:

- Exact sequences are precisely those chain complexes which are acyclic.

Given any chain complex, its homology can therefore be thought of as a measure of the degree to which it fails to be exact.

If we take a series of short exact sequences linked by chain complexes (that is, a short exact sequence of chain complexes, or from another point of view, a chain complex of short exact sequences), then we can derive from this a long exact sequence (i.e. an exact sequence indexed by the natural numbers) on homology by application of the zig-zag lemma. It comes up in algebraic topology in the study of relative homology; the Mayer–Vietoris sequence is another example. Long exact sequences induced by short exact sequences are also characteristic of derived functors.

Exact functors are functors that transform exact sequences into exact sequences.

References

- General

- Spanier, Edwin Henry (1995). Algebraic Topology. Berlin: Springer. p. 179. ISBN 0-387-94426-5.

- Adhikari, M.R.; Adhikari, Avishek (2003). Groups, Rings and Modules with Applications. India: Universities Press. p. 216. ISBN 81-7371-429-0.

- Citations

- ↑ "Divergenceless field". December 6, 2009.

External links

- Exact sequence at PlanetMath.org.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Exact Sequence", MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Short Exact Sequence", MathWorld.

| ||||||||||||||||