Evolution of primates

Evolutionary history of the primates can be traced back 65 million years. The oldest known primate-like mammal species,[1] the Plesiadapis, came from North America, but they were widespread in Eurasia and Africa during the tropical conditions of the Paleocene and Eocene.

Purgatorius is the genus of the four extinct species believed to be the earliest example of a primate or a proto-primate, a primatomorph precursor to the Plesiadapiformes, dating to as old as 66 million years ago.

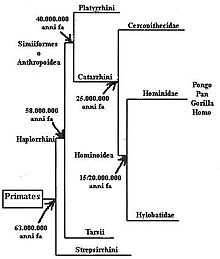

David Begun[2] concluded that early primates flourished in Eurasia and that a lineage leading to the African apes and humans, including Dryopithecus, migrated south from Europe or Western Asia into Africa. The surviving tropical population of primates, which is seen most completely in the upper Eocene and lowermost Oligocene fossil beds of the Faiyum depression southwest of Cairo, gave rise to all living species—lemurs of Madagascar, lorises of Southeast Asia, galagos or "bush babies" of Africa, and the anthropoids: platyrrhine or New World monkeys, catarrhines or Old World monkeys, and the great apes, which gave rise to the ancestors of Homo sapiens.

The earliest known catarrhine is Kamoyapithecus from uppermost Oligocene at Eragaleit in the northern Kenya Rift Valley, dated to 24 million years ago.[3] Its ancestry is thought to be species related to Aegyptopithecus, Propliopithecus, and Parapithecus from the Fayum, at around 35 million years ago.[4] In 2010, Saadanius was described as a close relative of the last common ancestor of the crown catarrhines, and tentatively dated to 29–28 million years ago, helping to fill an 11-million-year gap in the fossil record.[5]

In the early Miocene, about 22 million years ago, the many kinds of arboreally adapted primitive catarrhines from East Africa suggest a long history of prior diversification. Fossils at 20 million years ago include fragments attributed to Victoriapithecus, the earliest Old World Monkey. Among the genera thought to be in the ape lineage leading up to 13 million years ago are Proconsul, Rangwapithecus, Dendropithecus, Limnopithecus, Nacholapithecus, Equatorius, Nyanzapithecus, Afropithecus, Heliopithecus, and Kenyapithecus, all from East Africa.

The presence of other generalized non-cercopithecids of middle Miocene age from sites far distant—Otavipithecus from cave deposits in Namibia, and Pierolapithecus and Dryopithecus from France, Spain and Austria—is evidence of a wide diversity of forms across Africa and the Mediterranean basin during the relatively warm and equable climatic regimes of the early and middle Miocene. The youngest of the Miocene hominoids, Oreopithecus, is from coal beds in Italy that have been dated to 9 million years ago.

Molecular evidence indicates that the lineage of gibbons (family Hylobatidae) diverged from Great Apes some 18-12 million years ago, and that of orangutans (subfamily Ponginae) diverged from the other Great Apes at about 12 million years; there are no fossils that clearly document the ancestry of gibbons, which may have originated in a so-far-unknown South East Asian hominoid population, but fossil proto-orangutans may be represented by Sivapithecus from India and Griphopithecus from Turkey, dated to around 10 million years ago.[6]

Evolution of lemurs

Lemurs, in the suborder Strepsirrhini, had been isolated on the island of Madagascar between 42 and 50 mya, allowing for their independent evolution.

Human evolution

Evolution of color vision

Evolution of the pelvis

In primates, the pelvis consists of four parts - the left and the right hip bones which meet in the mid-line ventrally and are fixed to the sacrum dorsally and the coccyx. Each hip bone consists of three components, the ilium, the ischium, and the pubis, and at the time of sexual maturity these bones become fused together, though there is never any movement between them. In humans, the ventral joint of the pubic bones is closed.

The most striking feature of evolution of the pelvis in primates is the widening and the shortening of the blade called the ilium. Because of the stresses involved in bipedal locomotion, the muscles of the thigh move the thigh forward and backward, providing the power for bi-pedal and quadrupedal locomotion.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ [K. D. Rose -1994 DOI: 10.1002/evan.1360030505 ] - [J. Fleagle, C. Gilbert 2011-2012 ] - [J. Roach 2008 ] - [V. McMains - 2011 ] - [2009 & ] [Retrieved 2012-01-01]

- ↑ Kordos L, Begun D R (2001). "Primates from Rudabánya: allocation of specimens to individuals, sex and age categories". J. Hum. Evol. 40 (1): 17–39. doi:10.1006/jhev.2000.0437. PMID 11139358.

- ↑ David W. Cameron (2004). Hominid adaptations and extinctions. UNSW Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-86840-716-6. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ↑ David Rains Wallace (13 September 2005). Beasts of Eden: Walking Whales, Dawn Horses, and Other Enigmas of Mammal Evolution. University of California Press. pp. 240–. ISBN 978-0-520-24684-3. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ↑ Zalmout, I. S.; Sanders, W. J.; MacLatchy, L. M.; Gunnell, G. F.; Al-Mufarreh, Y. A.; Ali, M. A.; Nasser, A.-A. H.; Al-Masari, A. M. et al. (2010). "New Oligocene primate from Saudi Arabia and the divergence of apes and Old World Monkeys". Nature 466 (7304): 360–364. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..360Z. doi:10.1038/nature09094. PMID 20631798.

- ↑ Srivastava (2009). Morphology Of The Primates And Human Evolution. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. p. 87. ISBN 978-81-203-3656-8. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ↑ Bernard Grant Campbell (1998). Human Evolution: An Introduction to Mans Adaptations. Transaction Publishers. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-202-02042-6. Retrieved 30 July 2012.