Evolution of cetaceans

The cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises) are marine mammal descendants of land mammals. Their terrestrial origins are indicated by:

- Their need to breathe air from the surface;

- The bones of their fins, which resemble the limbs of land mammals

- The vertical movement of their spines, characteristic more of a running mammal than of the horizontal movement of fish.

The question of how a group of land mammals became adapted to aquatic life was a mystery until discoveries starting in the late 1970s in Pakistan revealed several stages in the transition of cetaceans from land to sea.

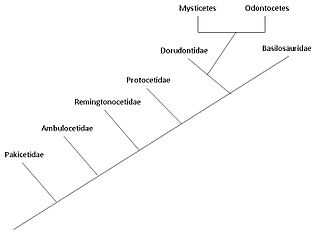

Earliest ancestors

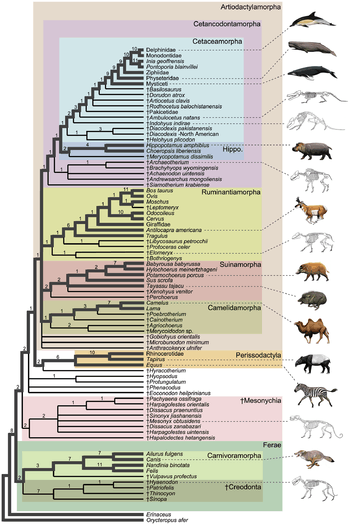

The traditional theory of cetacean evolution was that whales were related to the mesonychids, an extinct order of carnivorous ungulates (hoofed animals) that resembled wolves with hooves and were a sister group of the artiodactyls (even-toed ungulates). This theory arose due to similarities between the unusual triangular teeth of the mesonychids and those of whales. However, more recent molecular phylogeny data indicate that whales are more closely related to the artiodactyls, with hippopotamus as the closest living relative.[2] The strong evidence for a clade combining cetaceans and artiodactyls is further discussed in the article Cetartiodactyla. However, the earliest anthracotheres, the ancestors of hippos, do not appear in the fossil record until the Middle Eocene, millions of years after Pakicetus, the first known whale ancestor, appears during the Early Eocene, implying the two groups diverged well before the Eocene.

The molecular data is supported by the recent discovery of Pakicetus, the earliest proto-whale (see below). The skeletons of Pakicetus show that whales did not derive directly from mesonychids. Instead, they are artiodactyls that began to take to the water soon after artiodactyls split from mesonychids. Proto-whales retained aspects of their mesonychid ancestry (such as the triangular teeth) which modern artiodactyls have lost. An interesting implication is that the earliest ancestors of all hoofed mammals were probably at least partly carnivorous or scavengers, and today's artiodactyls and perissodactyls became herbivores later in their evolution. By contrast, whales retained their carnivorous diet, because prey was more available and they needed higher caloric content in order to live as marine endotherms. Mesonychids also became specialized carnivores, but this was likely a disadvantage because large prey was not yet common. This may be why they were out-competed by better-adapted animals like the creodonts and later Carnivora which filled the gaps left by the dinosaurs.

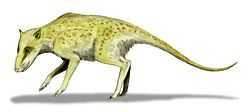

Indohyus

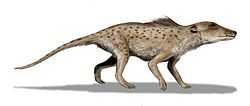

Indohyus was a small chevrotain-like animal that lived about 48 million years ago in what is now Kashmir.[4] It belongs to the artiodactyl family Raoellidae, and is believed to be the closest sister group of Cetacea.[1] About the size of a raccoon or domestic cat, this herbivorous creature shared some of the traits of whales, most notably the involucrum, a bone growth pattern which is the diagnostic characteristic of any cetacean, and is not found in any other species.[1] It also showed signs of adaptations to aquatic life, including a thick and heavy outer coating and dense limb bones that reduce buoyancy so that they could stay underwater, which are similar to the adaptions found in modern creatures such as the hippopotamus.[2][5] This suggests a similar survival strategy to the African mousedeer or water chevrotain which, when threatened by a bird of prey, dives into water and hides beneath the surface for up to four minutes.[6][7][8]

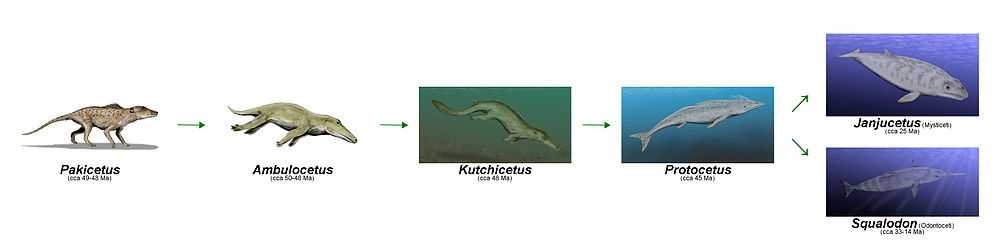

Pakicetidae

General

The pakicetids were digitigrade hoofed mammals that are thought to be the earliest known whales, with Indohyus being the closest sister group.[4][9] They lived in the early Eocene, around 50 million years ago. Their fossils were first discovered in North Pakistan in 1979, located at a river not far from the shores of the former Tethys Sea.[10] After the initial discovery, more fossils were found, mainly in the late-early Eocene fluvial deposits in northern Pakistan and northwestern India.[1] Based on this discovery, pakicetids most likely lived in an arid environment with ephemeral streams and moderately developed floodplains millions of years ago.[1] By using stable oxygen isotopes analysis, they were shown to drink fresh water.[11] Their diet probably included land animals that approached water for drinking or some freshwater aquatic organisms that lived in the river.[1] The elongated cervical vertebrae and the four, fused sacral vertebrae are consistent with Artiodactyla, making Pakicetidae one of the earliest fossils to be recovered from the period following the Cetacean/Artiodactyla divergence event.[12]

Skull morphology

Pakicetids were classified as cetaceans mainly based on the structure of the auditory bulla, which is formed from the ectotympanic bone only. The shape of the ear region in pakicetids is highly unusual and the skull is cetacean-like, although a blowhole is still absent at this stage. The jawbone of pakicetids also lacks the enlarged space (mandibular foramen) that is filled with fat or oil, which is used in receiving underwater sound in modern whales.[13] They have dorsal orbits (eye sockets facing up), which are similar to crocodiles. This eye placement helps submerged predators observe potential prey above the water.[11] According to Thewissen et al., the teeth of pakicetids also resemble the teeth of fossil whales, being less like a dog's incisors, with a serrated triangular shape, similar to a shark's tooth, which is another link to more modern whales.[14] It was initially thought that the ears of pakicetids were adapted for underwater hearing, but, as would be expected from the anatomy of the rest of this creature, the ears of pakicetids are specialized for hearing on land.[15] However, pakicetids were able to listen underwater, by using enhanced bone conduction, rather than depending on tympanic membrane like general land mammals. This method of hearing does not give directional hearing underwater.[13]

Postcranial morphology

Pakicetids have long thin legs, with relatively short hands and feet which suggest that they were poor swimmers.[1] To compensate for that, their bones are unusually thick (osteosclerotic), which is probably an adaptation to make the animal heavier to counteract the buoyancy of the water.[3] According to a morphological analysis by Thewissen et al., pakicetids display no aquatic skeletal adaptation; instead they display adaptations for running and jumping.[16] Hence pakicetids were most likely an aquatic wader.

Ambulocetidae

General

Ambulocetus natans, which lived about 49 million years ago, was discovered in Pakistan in 1994. It was probably amphibious, and resembled the crocodile in its physical appearance.[16] In the Eocene, ambulocetids inhabited the bays and estuaries of the Tethys Ocean in northern Pakistan.[1] The fossils of ambulocetids are always found in near-shore shallow marine deposits associated with abundant marine plant fossils and littoral molluscs.[1] Although they are found only in marine deposits, their oxygen isotope values indicate that they consumed a range of water with different degree of salinity, with some specimens having no evidence of sea water consumption and others that did not ingest fresh water at the time when their teeth are fossilized. It is clear that ambulocetids tolerated a wide range of salt concentrations.[11] Hence, ambulocetids represent a transition phase of cetacean ancestors between fresh water and marine habitat.

Skull morphology

The mandibular foramen in ambulocetids had increased in size, which indicates that a fat pad was likely to be housed in the lower jaw. In modern whales, this fat pad in the mandibular foramen extends posteriorly to the middle ear. This allows sounds to be received in the lower jaw, and then transmitted through the fat pad to the middle ear.[11] Similar to pakicetids, the orbits of ambulocetids are on the dorsal side of the skull, but they face more laterally than in pakicetids.[11]

Postcranial morphology

Ambulocetids had relatively long limbs with particular strong hind legs, and they retained a tail with no sign of fluke (the horizontal tail fin of modern cetaceans).[10] The hindlimb structure of Ambulocetids shows that their ability to engage in terrestrial locomotor activity was significantly limited compared to that of contemporary terrestrial mammals. The skeletal structures of the knee and ankle indicate that the motion of the hindlimbs were restricted in one plane. This suggests that, on land, propulsion of the hindlimbs was powered by extension of dorsal muscles.[17] Although they could walk on land, as well as swim, it is clear that they were not fast in either environment.[18] It has been speculated that Ambulocetids hunted like crocodiles, lurking in the shallows to snatch unsuspecting riparian prey and fish.[16] They probably swam by pelvic paddling (a way of swimming which mainly utilizes their hind limbs to generate propulsion in water) and caudal undulation (a way of swimming which uses the undulations of the vertebral column to generate force for movements), as otters, seals and whales do.[19] This is an intermediate stage in the evolution of cetacean locomotion, as modern whales swim by caudal oscillation (a way of swimming similar to caudal undulation, but uses energy more efficiently).[11]

Remingtonocetidae

General

Remingtonocetids lived in middle-Eocene South Asia, about 49 to 43 million years ago.[20] Compared to family Pakicetidae and Ambulocetidae, Remingtonocetidae was a diverse family found in north and central Pakistan, and also western India.[1] Remingtonocetids were also found in shallow marine deposits, but they are obviously more aquatic than ambulocetidae. This can be seen from the recovery of their fossils from a variety of coastal marine environments, including near-shore and lagoonal deposits.[1] It is shown that most remingtonocetids did not ingest fresh water, and had hence lost their dependency on fresh water relatively soon after their origin.[11]

Skull morphology

The orbits of remingtonocetids face laterally and are small. This suggests that vision is not an important sense for them.[11] The nasal opening, which will later evolve to become the blowhole in modern cetaceans, is located near the tip of the long snout. The position of the nasal opening had remained unchanged since pakicetids.[11] One of the notable features in remingtonocetids is that the semicircular canals, which are important for balancing in land mammals, had decreased in size.[21] This reduction in size had closely accompanied the cetacean invasion of marine environments. According to Spoor et al., this modification of the semicircular canal system may represent a crucial ‘point of no return’ event in early cetacean evolution, which excluded a prolonged semi-aquatic phase.[21]

Postcranial morphology

Compared to ambulocetids, remingtonocetids had relatively short fore and hind limbs.[11] Based on their skeletal remains, remingtonocetids were probably amphibious whales that are well adapted to swimming, and likely to swim by caudal undulation only.[1]

Protocetidae

General

The protocetids form a diverse and heterogeneous group known from Asia, Europe, Africa, and North America. They lived in the Eocene, approximately 48 to 35 million years ago.[11] The fossil remains of protocetids were uncovered from coastal and lagoonal facies in South Asia; but unlike previous cetacean families, their fossils uncovered from Africa and North America also include open marine forms.[1] Hence they were probably amphibious, but more aquatic compared to remingtonocetids.[20] Protocetids were the first whales to leave the Indian subcontinent and disperse to all shallow subtropical oceans of the world.[11] There were many genera among the family Protocetidae, and some of these are very well known (e.g., Rodhocetus). Great variations in aquatic adaptations exist among them, with some probably able to support their weight on land, whereas others could not.[1] Their supposed amphibious nature is supported by the discovery of a pregnant Maiacetus,[22] in which the fossilised fetus was positioned for a head-first delivery, suggesting that Maiacetus gave birth on land.

Skull morphology

Unlike remingtonocetids and ambulocetids, protocetids have large orbits which are oriented laterally. Increasingly lateral-facing eyes might be used to observe underwater prey, and are similar to the eyes of modern cetaceans.[11] Furthermore, the nasal openings are large and are now halfway up the snout.[11] The great variety of teeth suggests diverse feeding modes in protocetids.[20] In both remingtonocetids and protocetids, the size of mandibular foramen had increased.[11] The large mandibular foramen indicates that the mandibular fat pad was present. However the air-filled sinuses that are present in modern cetaceans, which function to isolate the ear acoustically to enable better underwater hearing, are still not present.[13] The external auditory meatus (ear canal) which is absent in modern cetaceans is also present. Hence, the method of sound transmission present in them combines aspects of pakicetids and modern odontocetes (toothed whales).[13] At this intermediate stage of hearing development, the transmission of airborne sound was poor due to the modifications of ear for underwater hearing; while directional underwater hearing was also poor compared to modern cetaceans.[13]

Postcranial morphology

Some protocetids had short, large fore- and hindlimbs that are likely to be used in swimming, but the limbs give a slow and cumbersome locomotion on land.[11][18] It is possible that some protocetids had flukes.[18] However, it is clear that they are adapted even further to an aquatic life-style. In Rodhocetus, for example, the sacrum (a bone that in land-mammals is a fusion of five vertebrae that connects the pelvis with the rest of the vertebral column) was divided into loose vertebrae. However, the pelvis was still connected to one of the sacral vertebrae. The ungulate ancestry of these early whales is still underlined by characteristics like the presence of hooves at the ends of the toes in Rodhocetus.

Locomotion

The foot structure of Rodhocetus shows that protocetids were predominantly aquatic. Gingerich et al. hypothesized that Rodhocetus locomoted in oceanic environment similarly to Ambulocetids pelvic paddling supplemented by caudal undulation. Terrestrial locomotion of Rodhocetus was very limited due to their hindlimb structure. It is thought that they moved in a way similar to how eared seals move on land.[23]

Basilosauridae and Dorudontinae

General

Basilosaurids were discovered in 1840 and initially mistaken for a reptile, hence its name. Together with dorudontids, they lived in the late Eocene around 41 to 35 million years ago, and are the oldest known obligate aquatic cetaceans.[1][15] They were fully recognizable whales which lived entirely in the ocean. This is supported by their fossils usually found in deposits indicative of fully marine environments, lacking any freshwater influx.[1] They were probably distributed throughout the tropical and subtropical seas of the world.[1] Basilosaurids are commonly found in association with dorudontids. In fact, they are closely related to one another.[11] The fossilised stomach contents in one basilosaurid indicates that it ate fish.[1]

Skull morphology

Although they look very much like modern whales, basilosaurids and dorudontids lacked the 'melon organ' that allows their descendants to use echolocation as effectively as modern whales. They had small brains; this suggests they were solitary and did not have the complex social structure of some modern cetaceans. The mandibular foramen of basilosaurids and dorudontids now cover the entire depth of the lower jaw as in modern cetaceans.[11] Their orbits face laterally, and the nasal opening had moved even higher up the snout, closer to the position of blowhole in modern cetaceans.[11] Furthermore, their ear structures are functionally modern, with the major innovation being the insertion of air-filled sinuses between ear and skull.[13] Unlike modern cetaceans, basilosaurids retain a large external auditory meatus.[13]

Postcranial morphology

Both basilosaurids and dorudontids have skeletons that are immediately recognizable as cetaceans. A basilosaurid was as big as the larger modern whales, up to 18 m (60 ft) long; dorudontids were smaller, about 5 m (16 ft) long. The large size of basilosaurids is due to the extreme elongation of their lumbar vertebrae. They had a tail fluke, but their body proportions suggest that they swam by caudal undulation and that the fluke was not used for propulsion.[1] In contrast, dorudontids had a shorter but powerful vertebral column. They too had a fluke, and unlike basilosaurids, they probably swam similarly to modern cetaceans, by using caudal oscillations.[1][11] The forelimbs of basilosaurids and dorudontids were probably flipper-shaped, and the external hind limbs were tiny and are certainly not involved in locomotion.[1] Their fingers, on the other hand, still retain the mobile joints of their ambulocetid relatives. The two tiny but well-formed hind legs of basilosaurids which were probably used as claspers when mating; they are a small reminder of the lives of their ancestors. Interestingly, the pelvic bones associated with these hind limbs were now no longer connected to the vertebral column as they were in protocetids. Essentially, any sacral vertebrae can no longer be clearly distinguished from the other vertebrae.

Ancestry of modern Cetacea

Both basilosaurids and dorudontids are relatively closely related to modern cetaceans, which belong to suborders Odontoceti and Mysticeti. However, according to Fordyce and Barnes, the large size and elongated vertebral body of basilosaurids preclude them from being ancestral to extant forms. As for dorudontids, there are some species within the family that do not have elongated vertebral bodies, which might be the immediate ancestors of Odontoceti and Mysticeti.[20]

Early echolocation

Toothed whales (Odontocetes) echolocate by creating a series of clicks emitted at various frequencies. Sound pulses are emitted through their melon-shaped foreheads, reflected off objects, and retrieved through the lower jaw. Skulls of Squalodon show evidence for the first hypothesized appearance of echolocation. Squalodon lived from the early to middle Oligocene to the middle Miocene, around 33-14 million years ago. Squalodon featured several commonalities with modern Odontocetes. The cranium was well compressed, the rostrum telescoped outward (a characteristic of the modern suborder Odontoceti), giving Squalodon an appearance similar to that of modern toothed whales. However, it is thought unlikely that squalodontids are direct ancestors of living dolphins.

Early baleen whales

All modern mysticetes are large filter-feeding or baleen whales, though the exact means by which baleen is used differs among species (gulp-feeding with balaenopterids, skim-feeding with balaenids, and bottom plowing with eschrichtiids). The first members of some modern groups appeared during the middle Miocene. Filter feeding is very beneficial as it allows modern baleen whales to efficiently gain huge energy resources, which makes the large body size in modern baleen whales possible.[24] These changes may have been a result of worldwide environmental change and physical changes in the oceans. A large scale change in ocean current and temperature could have initiated the radiation of modern mysticetes, leading to the demise of the archaic forms. Generally it is speculated the four modern mysticete families have separate origins among the cetotheres. Modern baleen whales, Balaenopteridae (rorquals and humpback whale, Megaptera novaengliae), Balaenidae (right whales), Eschrichtiidae (gray whale, Eschrictius robustus), and Neobalaenidae (pygmy right whale, Caperea marginata) all have derived characteristics presently unknown in any cetothere.

Early dolphins

During the early Miocene (about 20 Ma), echolocation developed in its modern form. Various extinct dolphin-like families flourished. Early dolphins include Kentriodon and Hadrodelphis. These belong to Kentriodontidae, which were small to medium-sized toothed cetaceans with largely symmetrical skulls, and thought likely to include ancestors of some modern species. Kentriodontids date to the late Oligocene to late Miocene. Kentriodontines ate small fish and other nectonic organisms; they are thought to have been active echolocators, and might have formed schools. Diversity, morphology and distribution of fossils appear parallel to some modern species.

Skeletal evolution

.png)

Today, the whale hind parts are internal and reduced. Occasionally, the genes that code for longer extremities cause a modern whale to develop miniature legs (known as atavism).

Pakicetus had a pelvic bone most similar to that of terrestrial mammals. As the pelvic bone changed throughout species, Basilosaurids had a pelvic bone that was no longer attached to the vertebrae and the ilium was reduced. [25]

Modern cetaceans have rudimentary hind limbs, such as reduced femurs, fibulas, and tibias, and a pelvic girdle, consisting of an ilium, ischium, and pubis bone. Cetacean hind limbs and bones of the pelvic girdle can be compared to terrestrial mammals. Indohyus has a thickened ectotympanic internal lip of the ear bone. This feature compares directly to that of the cetacean. The most striking similar feature was that of the composition of the teeth of Indohyus. The composition of the teeth contained mostly calcium phosphate, which is needed for eating and drinking of aquatic animals. The next evolutionary change was to the first actual cetacean known as pakicetids. Although they somewhat resembled a wolf on the outside, the skeleton showed eye sockets were much closer to the tops of their heads than normal. This compared to the structure of the eyes in cetaceans. The pakicetids made the most dramatic change, going from land to water. This lead to rebuilding of the skull and food processing equipment because the eating habits were changing. Ultimately, the change in position of the eyes and limb bones is what lead the pakicetids to become waders. The next evolutionary changed occurred to that of the first marine cetaceans, Ambulocetidae. The ambulocetids also began to develop long snouts, which we see in current cetaceans. Limbs were compared closely to otters because of the swimming that occurred with their hind legs. The evolution of the skeleton continues to change until the modern day cetaceans known as odontocetes and the mysticetes. Over the course of evolution, the cetacean skeletal structure went through many alterations that now make it very distinguishable from terrestrial mammals.

Certain genes are believed to be responsible for the changes that occurred to the cetacean pelvic structure and hind limbs. Possible gene candidates for modifications made to the cetacean pelvic girdle include BMP7, PBX1, PBX2, Prrx1, and Prrx2.[26] These genes all serve a purpose in pelvic girdle development in different animal species. Different genes are thought to be responsible for the evolution of cetacean hind limbs. One potential gene that could be involved in hind limb reduction is called the Shh gene. This gene is thought to be responsible for the reduction of distal portions of hind limbs. Another gene that could be involved in hind limb reduction is called the Tbx4 gene. The Tbx4 gene is responsible for hind limb development in humans and mice, and researchers compared the Tbx4 gene in cetacean development with the Tbx4 gene in human and mice development to determine if the gene acts differently in cetaceans.[27] The pelvic girdle and reduced hind limbs in modern cetaceans were once thought to be vestigial structures that served no purpose at all. It is now believed that the pelvic girdle does serve a useful purpose. The pelvic girdle in male cetaceans is different in size compared to females, and the size is thought to be a result of sexual dimorphism. The pelvic bones of modern male cetaceans are more massive, longer, and larger than those of females. They are also involved in supporting male genitalia that remain hidden behind abdominal walls until sexual reproduction occurs.[28][29] [30]

Whereas early cetaceans such as Pakicetus had the nasal openings at the end of the snout, in later species such as Rodhocetus, the openings had begun to drift toward the top of the skull. This is known as nasal drift.

The nostrils of modern whales have become modified into blowholes that allow them to break to the surface, inhale, and submerge with convenience. The ears began to move inward as well, and, in the case of Basilosaurus, the middle ears began to receive vibrations from the lower jaw. Today's modern toothed whales use the 'melon organ', a pad of fat, for echolocation.

Modern Evolution of Cetaceans

Culture and social networks have played a large role in the evolution of modern Cetaceans, as shown in recent research showing dolphins preferring mates with the same socially-learned behaviors and humpback whales using songs between breeding areas.[31] For dolphins particularly, the largest non-genetic effects on their evolution seem to be due to culture, social structure, and environmental factors.

Culture

First of all, culture is defined as group-specific behavior transferred by social learning. [32] One of the best examples for dolphins where culture affects evolution involves tool use and foraging. Generally speaking, whether or not a dolphin uses a tool affects their eating behavior, which therefore causes differences in diet. Also, using a tool allows a new niche and new prey to open up for that particular dolphin. Due to these differences, fitness levels change within the dolphins of a population, which further causes evolution to occur in the long run.

Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphins

Based on recent research, the population of Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops sp.) around Shark Bay of Western Australia can be divided into spongers and nonspongers. Spongers put sponges on their noses as a protective means against abrasions from sharp objects, stingray barbs, or toxic organisms. The sponges also help the dolphins target fish without swim bladders, since echolocation cannot detect these fish easily against a complex background. Spongers also specifically forage in deep channels, but nonspongers are found foraging in both deep and shallow channels.[33] It has also been discovered that this foraging behavior seems to be passed on from mother to daughter/son most of the time.[34] Therefore, since this is a group behavior being passed down by social learning, this tool use is considered a culture.

In a recent experiment with these Shark Bay populations, researchers compared data from the East and West Gulf of Shark Bay, deep and shallow channels, and sponger vs. nonsponger dolphins. In order to test differences of diet, they took superficial blubber samples and performed a fatty acid analysis. Overall, the researchers found the fatty acid analyses to differ between West and East Gulf, which is simply due to the two areas having different food sources. However, when comparing data from within the West Gulf, the spongers vs. the nonspongers in the deep channels had very different fatty acid analyses even though the habitat is the same. Meanwhile, nonspongers from deep and shallow channels had similar data. This suggests that sponging was the cause of the different data and not the deep vs. shallow channels. Sponging opened up a new niche for the dolphins and allowed them access to new prey, thereby causing long-term diet changes.[35] By producing different food sources within a population, there is less intrapopulation competition for resources, showing ecological character displacement. As a result, carrying capacity actually increases since the entire population does not depend on one food source. Meanwhile, the fitness levels within the population also change, thus allowing evolution to act on this culture.

Social Structure

In addition, social networks within a population correlate with culture, further leading to evolution as well. Social structure forms groups that interact with one another, and this allows for cultural traits to emerge, flow, and evolve. This relationship is especially seen in the bottlenose dolphin populations in southwestern Australia, who have been known to beg for food from fishermen. Research shows that this begging behavior spread through the population due to two types of learning: individual (dolphins spending time around boats) and social (dolphins spending time with other dolphins who express begging behavior).[36] This further displays how the social structure (who/where the dolphin spends time) affects the individual’s behavior and overall culture.

In the opposite way, culture can impact social structure by causing behavior matching and assortative mating. Individuals with a certain culture are more likely to associate/mate with individuals using the same behaviors rather than a random individual, thus influencing social groups and structure. For example, the sponger dolphins of Shark Bay preferentially stick with other spongers.[37] As another example, some bottlenose dolphins in Moreton Bay of Australia followed prawn trawlers to feed on their debris, while other dolphins in the same population did not follow them. The dolphins preferentially associated with individuals with same behavior even though they all lived in the same habitat. Later on, prawn trawlers were no longer present, and the dolphins integrated into one social network after a couple of years.[38] The integration of social networks after culture no longer differed exemplifies the major effect of culture on social structure.

Without relating to culture, social networks can still affect and cause evolution on their own by impending fitness differences on individuals.[39] In a longitudinal study performed on bottlenose dolphins, the early social bonds formed by male calves and their resulting survival rates were analyzed. According to the data, male calves had a lower survival rate if they had stronger bonds with juvenile males. However, when other age and sex classes were tested, their survival rate did not significantly change.[40] This suggests that juvenile males impose a social stress on their younger counterparts. In fact, it has been documented that juvenile males commonly perform acts of aggression, dominance, and intimidation against the male calves.[41] Thus, the fitness and survival rates of these male calves decrease, demonstrating how selection acts on these social bonds early in the calves’ lives.

In another experiment of bottlenose dolphins in the East Gulf of Shark Bay, fitness of female dolphins was measured by the success of their own calves. The research revealed differences in fitness within the population, and two possible explanations due to social bonds were suggested. First of all, the differences could be due to social learning (whether or not the mother passed on her knowledge of reproductive ability to the calves). It could also be due to the strong association between mother dolphins in the population; by sticking in a group, an individual mother does not need to be as vigilant all the time for predators.[42] Overall, this social learning and homophily seem to increase fitness of female dolphins, thus causing an selection for these traits and evolution.

Environmental Factors

Lastly, the environment has strongly affected the diversification, separation, and evolution of multiple dolphin species.

Yangtze River Dolphin

Recent genome sequences revealed that the Yangtze River dolphin (Lipotes vexillifer) lacks single nucleotide polymorphisms in the baiji genome. After reconstructing the history of the baiji genome for this dolphin species, researchers found that the major decrease in genetic diversity occurred most likely due to a bottleneck event during the last deglaciation. During this time period, sea levels were rising while global temperatures were decreasing. Other historical climate events can be correlated and matched with the genome history of the Yangtze River dolphin as well.[43] This shows how global and local climate change can drastically affect a genome, leading to changes in fitness, survival, and evolution of a species.

European Common Dolphin

The European common dolphins (Delphinus delphis) in the Mediterranean have differentiated into two types: western and eastern. According to research, this seems to be due to a recent bottleneck as well, which drastically decreased the size of the eastern Mediterranean population. Also, the lack of population structure between the western and eastern regions seems contradictory of the distinct population structures between other regions of dolphins, proving again of their differentiation.[44] Even though the dolphins in the Mediterranean area had no physical barrier between their regions, they still differentiated into two types due to ecology and biology. Therefore, the differences between the eastern and western dolphins most likely stems from highly specialized niche choice rather than just physical barriers. Through this, environment plays a large role in the differentiation and evolution of this dolphin species.

Bottlenose Dolphin

The divergence and speciation within this genus has been largely due to climate and environmental changes over history. According to research, the divisions within the genus correlate with periods of rapid climate change. For example, the changing temperatures could cause the coast landscape to change, niches to empty up, and opportunities for separation to appear.[45] In the Northeast Atlantic specifically, genetic evidence suggests that the bottlenose dolphins have differentiated into a coastal and pelagic type. Divergence seems most likely due to a founding event where a large group separated. Following this event, the separate groups adapted accordingly and formed their own niche specializations and social structures. These differences caused the two groups to diverge and to remain separated.[46]

Short-finned Pilot Whales in Japan

Two endemic, distinctive types of this species, Tappanaga or Shiogondou the larger, northern form and Magondou the smaller, southern form can be found along the Japanese archipelago where distributions of these two types mostly do not overlap by the oceanic front border around the easternmost point of Honshu. Some indicate that the local extinction of Long-finned Pilot Whales in North Pacific in the 12th century could have triggered the appearance of Tappanaga, causing Short-finned Pilots to colonize into colder ranges of the long-finned variant. [47] although some claim that Tappanaga's existence today is not a result of Short-finned pilots to refill niches of Pacific Long-finned Pilots but rather being a distinctive species of own by nature.

See also

- Aquatic adaptation

- Archaeoceti

- Evolution of mammals

- Evolution of sirenians

- Indohyus

- List of extinct cetaceans

- Transitional form

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 Thewissen, J. G. M.; Williams, E. M. (1 November 2002). "THE EARLY RADIATIONS OF CETACEA (MAMMALIA): Evolutionary Pattern and Developmental Correlations". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 33 (1): 73–90. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.020602.095426.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 University Of California, Berkeley (2005, February 7). "UC Berkeley, French Scientists Find Missing Link Between The Whale And Its Closest Relative, The Hippo". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Thewissen, J. G. M.; Cooper, Lisa Noelle; Clementz, Mark T.; Bajpai, Sunil; Tiwari, B. N. (20 December 2007). "Whales originated from aquatic artiodactyls in the Eocene epoch of India". Nature 450 (7173): 1190–1194. Bibcode:2007Natur.450.1190T. doi:10.1038/nature06343. PMID 18097400.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Northeastern Ohio Universities Colleges of Medicine and Pharmacy (2007, December 21). "Whales Descended From Tiny Deer-like Ancestors". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ University Of Michigan (2001, September 20). "New Fossils Suggest Whales And Hippos Are Close Kin". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ Carl Zimmer (2007-12-19). "The Loom : Whales: From So Humble A Beginning.". ScienceBlogs. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ Ian Sample (2007-12-19). "Whales may be descended from a small deer-like animal". Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ PZ Myers (2007-12-19). "Pharyngula: Indohyus". Pharyngula. ScienceBlogs. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ Philip D. Gingerich, D. E. Russell (1981). "Pakicetus inachus, a new archaeocete (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the early-middle Eocene Kuldana Formation of Kohat (Pakistan)". Univ. Mich. Contr. Mus. Paleont 25: 235–246.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Castro, E. Huber, Peter, Michael (2003). Marine Biology (4 ed). McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 11.9 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 11.14 11.15 11.16 11.17 11.18 11.19 THEWISSEN, J. G. M.; BAJPAI, SUNIL (1 January 2001). "Whale Origins as a Poster Child for Macroevolution". BioScience 51 (12): 1037. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[1037:WOAAPC]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0006-3568.

- ↑ Uhen, (2010). The Origin(s) of Whales. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 38: 189–219.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 Nummela, Sirpa; Thewissen, J. G. M.; Bajpai, Sunil; Hussain, S. Taseer; Kumar, Kishor (11 August 2004). "Eocene evolution of whale hearing". Nature 430 (7001): 776–778. Bibcode:2004Natur.430..776N. doi:10.1038/nature02720. PMID 15306808.

- ↑ Whale Origins

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 J. G. M. Thewissen, E. M. Williams, L. J. Roe and S. T. Hussain (2001). "Skeletons of terrestrial cetaceans and the relationship of whales to artiodactyls". Nature 413 (6853): 277–281. doi:10.1038/35095005. PMID 11565023.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Thewissen, J. G. M.; Williams, E. M.; Roe, L. J.; Hussain, S. T. (19 September 2001). "Skeletons of terrestrial cetaceans and the relationship of whales to artiodactyls". Nature 413 (6853): 277–281. doi:10.1038/35095005. PMID 11565023.

- ↑ Thewissen, J.G.M; S. T. Hussain M. Alif (14). "Fossil Evidence for the Origin of Aquatic Locomotion in Archaeocete Whales". Science 263 (5144): 210–212. doi:10.1126/science.263.5144.210. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 "The Thewissen Lab". Retrieved 12 Feb 2011.

- ↑ Thewissen, J. G. M; F.E.Fish (August 1997). "Locomotor Evolution in the Earliest Cetaceans: Functional Model, Modern Analogues, and Paleontological Evidence". Paleobiology 23: 482–490.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Fordyce, R E; Barnes, L G (30 April 1994). "The Evolutionary History of Whales and Dolphins". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 22 (1): 419–455. Bibcode:1994AREPS..22..419F. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.22.050194.002223.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Spoor, F.; Bajpai, S.; Hussain, S. T.; Kumar, K.; Thewissen, J. G. M. (8 May 2002). "Vestibular evidence for the evolution of aquatic behaviour in early cetaceans". Nature 417 (6885): 163–166. Bibcode:2002Natur.417..163S. doi:10.1038/417163a. PMID 12000957.

- ↑ Gingerich PD, ul-Haq M, von Koenigswald W, Sanders WJ, Smith BH et al. "New Protocetid Whale from the Middle Eocene of Pakistan: Birth on Land, Precocial Development, and Sexual Dimorphism". PLoS one. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ↑ Gingerich, Philip D; Munir ul Haq; Lyad S. Zalmout; Intizar Hyssain Khan; M. sadiq Malkani (21). "Origin of Whales from Early Artiodactyls: Hands and Feet of Eocene Protocetidae from Pakistan". Science 293: 2239. doi:10.1126/science/1063902. Check date values in:

|year=, |date=(help) - ↑ Demere, T.A.; McGowen, M.R.; Berta, A.; Gatesy, J. (2008). "Morphological and Molecular Evidence for a Stepwise Evolutionary Transition from Teeth to Baleen in Mysticete Whales". Systematic Biology 57: 15–37. doi:10.1080/10635150701884632.

- ↑ Thewiseen J, Cooper L, George J. 2009. From Land to Water: the Origin of Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises. Evolution Education Outreach [Internet]. [cited 2014 Sep 12] 2:272-288. Available from: http://osu.worldcat.org/title/from-land-to-water-the-origin-of-whales-dolphins-and-porpoises/oclc/439682860&referer=brief_results.

- ↑ Gol'din, Pavel. "Naming an Innominate: Pelvis and Hindlimbs of Miocene Whales Give an Insight into Evolution and Homology of Cetacean Pelvic Girdle." Evolutionary Biology 41: 473-479.

- ↑ Onbe, Kaori, Shin Nishida, Emi Sone, Naohisa Kanda, Mutsuo Goto, Luis A. Pastene, Shinsuke Tanabe,and Hiroko Koike. "Sequence Variation in the Tbx4 Gene in Marine Mammals." Zoological Science 24.5: 449-464.

- ↑ Gol'din, Pavel. "Naming an Innominate: Pelvis and Hindlimbs of Miocene Whales Give an Insight into Evolution and Homology of Cetacean Pelvic Girdle." Evolutionary Biology 41: 473-479.

- ↑ Onbe, Kaori, Shin Nishida, Emi Sone, Naohisa Kanda, Mutsuo Goto, Luis A. Pastene, Shinsuke Tanabe,and Hiroko Koike. "Sequence Variation in the Tbx4 Gene in Marine Mammals." Zoological Science 24.5: 449-464.

- ↑ Tajima, Yuko, Yoshihiro Hayashi, and Tadasu Yamada. "Comparative Anatomical Study on the Relationships between the Vestigial Pelvic Bones and the Surrounding Structures of Finless Porpoises.The Journal of Veterinary Medicine 66.7: 761-766

- ↑ Cantor, M.; Whitehead, H. (2013). "The interplay between social networks and culture: theoretically and among whales and dolphins". Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 368. doi:10.1098/rstb.2012.0340.

- ↑ Cantor, M., & Whitehead, H. (2013). The interplay between social networks and culture: theoretically and among whales and dolphins. Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 368. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0340

- ↑ Krutzen, M., Kreicker, S., Macleod, C. D., Learmonth, J., Kopps, A. M., Walsham, P., & Allen, S. J. (2014). Cultural transmission of tool use by Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops sp.) provides access to a novel foraging niche. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.0374

- ↑ Cantor, M., & Whitehead, H. (2013). The interplay between social networks and culture: theoretically and among whales and dolphins. Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 368. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0340

- ↑ Krutzen, M., Kreicker, S., Macleod, C. D., Learmonth, J., Kopps, A. M., Walsham, P., & Allen, S. J. (2014). Cultural transmission of tool use by Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops sp.) provides access to a novel foraging niche. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.0374

- ↑ Cantor, M., & Whitehead, H. (2013). The interplay between social networks and culture: theoretically and among whales and dolphins. Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 368. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0340

- ↑ Cantor, M., & Whitehead, H. (2013). The interplay between social networks and culture: theoretically and among whales and dolphins. Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 368. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0340

- ↑ Cantor, M., & Whitehead, H. (2013). The interplay between social networks and culture: theoretically and among whales and dolphins. Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 368. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0340

- ↑ Frere, C. H., Krutzen, M., Mann, J. Connor, R. C., Bejder, L., & Sherwin, W. B. (2010). Social and genetic interactions drive fitness variation in a free-living dolphin population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107, 19949-19954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007997107

- ↑ Stanton, M. A., & Mann, J. (2012). Early Social Networks Predict Survival in Wild Bottlenose Dolphins. PLoS One, 7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047508

- ↑ Stanton, M. A., & Mann, J. (2012). Early Social Networks Predict Survival in Wild Bottlenose Dolphins. PLoS One, 7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047508

- ↑ Frere, C. H., Krutzen, M., Mann, J. Connor, R. C., Bejder, L., & Sherwin, W. B. (2010). Social and genetic interactions drive fitness variation in a free-living dolphin population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107, 19949-19954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007997107

- ↑ Zhou, X., Sun, F., Xu, S., Fan, G., Zhu, K., Liu, X., … Yang, G. (2013). Baiji genomes reveal low genetic variability and new insights into secondary aquatic adaptations. Nature Communications, 4. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3708

- ↑ Moura, A. E., Natoli, A., Rogan, E., & Hoelzel, A. R. (2012). Atypical panmixia in a European dolphin species (Delphinus delphis): implications for the evolution of diversity across oceanic boundaries. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 26, 63-75. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12032

- ↑ Moura, A. E., Nielsen, S. C. A., Vilstrup, J. T., Moreno-Mayar, J. V., Gilbert, M. T. P., Gray, H. W. I., … Hoelzel, A. R. (2013). Recent Diversification of a Marine Genus (Tursiops spp.) Tracks Habitat Preference and Environmental Change. Systematic Biology, 62 (6), 865-877. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syt051

- ↑ Louis, M., Viricel, A., Lucas, T., Peltier, H., Alfonsi, E., Berrow, S., … Simon-Bouhet, B. (2014). Habitat-driven population structure of bottlenose dolphins, Tursiops truncatus, in the North-East Atlantic. Molecular Ecology, 23, 857-874. doi: 10.1111/mec.12653

- ↑ Amano M. (2012). "みちのくの海のイルカたち(特集 みちのくの海と水族館の海棲哺乳類)" (PDF). Isana (56), 60-65, 2012-06 (Faculty of Fisheries of University of Nagasaki, Isanakai). Retrieved 2015-01-19.

External links

For a review of whale evolution, see Uhen, M. D. (2010). "The Origin(s) of Whales". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 38: 189–219. Bibcode:2010AREPS..38..189U. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-040809-152453.

- Timeline of Whale Evolution - Smithsonian Ocean Portal

- Cetacean Paleobiology – University of Bristol

- BBC: Whale's evolution

- BBC: Whale Evolution – The Fossil Evidence

- Hooking Leviathan by Its Past by Stephen Jay Gould

- Whale Origins, Thewissen Lab, Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine

- Digital Library of Dolphin Development, Thewissen Lab

- Research on the Origin and Early Evolution of Whales (Cetacea), Gingerich, P.D., University of Michigan

- Pakicetus inachus, a new archaeocete (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the early-middle Eocene Kuldana Formation of Kohat (Pakistan). Gingerich, P.D., 1981, Museum of Paleontology, The University of Michigan

- Skeletons of terrestrial cetaceans and the relationship of whales to artiodactyls, Nature 413, 277–281 (20 September 2001), J. G. M. Thewissen, E. M. Williams, L. J. Roe and S. T. Hussain

- Evolution of Whales segment from the Whales Tohorā Exhibition Minisite of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||