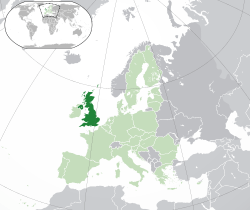

Euroscepticism in the United Kingdom

Euroscepticism, the opposition to policies of supranational EU institutions and/or opposition to Britain's membership of the European Union, has been a significant element in the politics of the United Kingdom (UK).

The European Unity movement as a political project after 1945 was supported and inspired by important British voices. E.g. Winston Churchill pledged in his 1946 Zurich speech for "a kind of United States of Europe" lead by France and Germany but did not intend to involve Britain.[1] The ambivalent position of British politics and citizens has been described as "wishing to seem an important part of Europe without being a part of it".[2] The othering of European Unity as a Continental issue and somebody else's problem has been rather strong.[3] Pro-European British politicians and citizens have faced various defeats and humiliations with regard to Britain's steps in the direction of increased European integration.[4] Even parties like the Liberal Democrats with an outspoken pro-European platform stay either in a minority position respectively have members that share the British lack of enthusiasms "of all things European."[5] After joining the EU, confrontational attitudes of British politicians, as in the UK rebate controversy, gained further popularity among the British public, while the advantages of the European Union were taken for granted.[2]

History

The ideological split between reverence for continental European refinery and classics and an emerging, especially antifrench, antigerman or general anti European sentiment is strong since various centuries. As in splendid isolation, self-definition and othering always includes projections of internal conflicts and differences. While having some overlap, Euroscepticism is somewhat different from Anti-Europeanism. Anti-Europeanism has always a strong influence in especially American culture and American exceptionalism, which sometimes sees Europe on the decline or as a rising rival power, or both.[6] Some aspects of British Euroscepticism have been mirrored and parroted by US anti-European authors[6] and the American discussion has influenced positions in Britain.

After 1945

Britain was urged to join and lead western Europe in the immediate aftermath of the War. The American Committee for a United Europe and the European Conference on Federation led by Winston Churchill were among the early endeveaours for European unity with British participation. However, British governments and political mainstream players, while advocating stronger integration of the Continent, did not intend to take part themselves. Britain never had a strong pro-European movement like the one founded in post-war Germany. The postwar years up to 1954 saw the UK occupied with the dissolution of its global Empire. It was not among the six founding member states of the European Communities in the early 1950s. The Six signed the Treaty of Paris, creating the European Coal and Steel Community, on 18 April 1951 but failed to create a European Defence Community.

In the years before, only the British extreme right – in particular Fascist politician Oswald Mosley– were rather outspoken, based on the Union Movement and the Europe a Nation slogan, for a stronger integration of Britain with Europe.[7][8] The British elites did not assume Britain should or could take part as a simple member in the European communities at that time.[9] The reservation was based less on economic considerations, since European integration would have offset the decreasing importance of the inter-Commonwealth trade,[10] but rather on political philosophy.[10] In Britain, the concept of unlimited sovereignty, based on the British legal system and parliamentary tradition was, and is, held in high esteem and presents a serious impediment to attempts at integration into a Continental legal framework.[10] The democratic deficit in the European Union, including legitimacy problems of the European Commission and the European Parliament is besides the supremacy of EU law over national legislation among the basic points of British EU-sceptics. As well rising costs of membership,[11] or an alleged negative impact of EU regulatory burdens on UK business are being mentioned.[12]

Opponents of the EU have accused its politicians and civil servants of corruption. A media scoop of this sort was 2005 Nigel Farage MEP request of the European Commission to disclose the individual Commissioner holiday travel, after President of the European Commission, José Barroso had spent a week on the yacht of the Greek shipping billionaire Spiro Latsis.[13][14] The European Court of Auditors reports about the financial planning are as well among the topics which are often scandalized in the British press.[15] The Better Off Out campaign, run by Simon Richards, is a non-partisan organisation campaigning for EU withdrawal and lists its reasons for EU withdrawal as freedom to make trading deals with other nations, control over national borders, control over UK government spending, the restoration of the British legal system, deregulation of EU laws and control of the NHS among others.[16]

The Labour Party party leader Hugh Gaitskell once declared that joining the European Communities would mean "the end of a thousand years of history".[17] Some Gaitskellites though (including the later founders of the SDP) were favourable to British involvement. Labour later changed from its initial opposition towards the European Community and began to support membership. Important groups of Conservatives also opposed joining the Common Market. One of the earliest groups formed against British involvement in Europe was the initially Conservative Party-based Anti-Common Market League, whose president Victor Montagu declared that opponents of the Common Market did not want to "subject [themselves] to a lot of frogs and huns".[18] Conversely, much of the opposition to Britain's EU membership initially came from Labour politicians and trade unionists who feared bloc membership would impede socialist policies, although this was never the universal Labour Party opinion. 2002 a minority of Labour MPs, and others such as Lord Healey, formed the Labour Against the Euro group in 2002, opposing British membership of the single currency.[19] The TUC remains strongly pro-EU,[20] but some of Labour's opponents in the media claim Ed Balls, the shadow chancellor, is privately a Eurosceptic.[21][22]

Impact of the Suez Crisis 1956

Even before the events of the Suez Crisis 1956, the United Kingdom had faced strains in its relationship with the USA. After the Suez conflict it had finally to accept that it could no longer assume that it was the preferred partner of the United States and underwent a massive loss of trust in the special relationship with the US.[23] Britain, along with Denmark, Ireland and Norway then started to prepare for a trading union, as in the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). British politicians, such as Labour's George Brown were in 1962 still of opinion, that Britain should not only be allowed to join, but be welcomed to lead the European Union, and met then with ridicule resp. neglection.[3]

In the 1960s the membership attempts of Conservative UK governments faced strong resistance from the Continent, especially from the French president, Charles de Gaulle.[9] Instead of being offered a leadership role, Britain was put on a yearlong waiting list, a major political humiliation for pro-European Britons. De Gaulle's veto in 1963 was a devastating blow for Harold Macmillan,[4] who, according Hugo Young, was not the last Tory politician to end his or her career as a result of European affairs. The UK faced a major economic decline and a row of disturbing political scandals as well. The combination did not help much with the Europe's image in the UK, and vice versa. With Georges Pompidou replacing Charles de Gaulle, the veto was finally lifted and negotiations began in 1970 under the pro-European government of Edward Heath. Heath had to deal with disagreements relating to the Common Agricultural Policy and the remaining relationship with the Commonwealth of Nations. 1972 the accession treaties were signed with all but Norway.

Admission and referendum

Despite the decision to join the European Community, internal Labour divisions over EEC membership prompted the Labour Party to propose a referendum be held on the permanence of the UK in the Communities. Originally proposed in 1972 by Tony Benn[24] (known as Anthony Wedgwood Benn at the time), Labour's referendum proposal led the anti-EEC Conservative politician Enoch Powell to advocate a Labour vote (initially only inferred) in the February 1974 election,[25] which was thought to have influenced the result, a return to government of the Labour Party. The eventual referendum in 1975 asked the voters:

"Parliament has decided to consult the electorate on the question whether the UK should remain in the European Economic Community: Do you want the UK to remain in the EEC?"

British membership of the EEC was endorsed by 67% of those voting, with a turnout of 64.5%. To date, the electorate has not been allowed to vote on membership of a European Union.

From 1975 to 1997

The debate between Eurosceptics and EU supporters is ongoing within, rather than between, British political parties, whose membership is of varied standpoints. The two main political parties in Britain, the Conservative Party (in government) and the Labour Party (in opposition) both have within them a broad spectrum of views concerning the European Union.

In the 1970s and early 1980s the Labour Party was the more Eurosceptic of the two parties, with more anti-European Communities MPs than the Conservatives. In 1975, Labour held a special conference on British membership and the party voted 2 to 1 for Britain to leave the European Communities.[26] In 1979, the Labour manifesto[27] declared that a Labour government would "oppose any move towards turning the Community into a federation" and, in 1983,[28] it still favoured British withdrawal from the EEC.

Under the leadership of Neil Kinnock after 1983, however, the then oppositional party dropped its former resistance to the European Communities and instead favoured greater British integration into European Economic and Monetary Union. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher however gained much popularity with the so-called UK rebate in 1984. Britain then managed to reduce its contributions to the Union to a certain extent, as it was then the EU's second poorest member and, without much agriculture, benefited little from farm subsidies.[29]

A speech by Jacques Delors, then President of the European Commission, at the TUC conference in 1988 helped to weaken the eurosceptic inclination in the Labour Party.[21] In the context of Margaret Thatcher's Conservative premiership, when policies to reduce the power of the trade unions were pursued, Delors' advocacy of a "social Europe" became attractive to many.[30] However the UK rebate have been held up as well by following Prime ministers.[29] In late October 1990, just before her premiership ended, Mrs Thatcher reacted strongly against Delors' plans for a single currency in the House of Commons;[31] her stance contributed to her downfall a few weeks later.[32]

Since 1997

The financier Sir James Goldsmith had formed the Referendum Party as a single-issue party to fight the 1997 General Election, calling for a referendum on aspects of the UK's relationship with the European Union. It planned to contest every constituency where there was no leading candidate in favour of such a referendum, and briefly held a seat in the House of Commons after George Gardiner, the Conservative MP for Reigate, changed parties in March 1997 following a battle against deselection by his local party. The party polled 800,000 votes and finished fourth, but did not win a seat in the House of Commons. The United Kingdom Independence Party, advocating the UK's complete withdrawal from the European Union, had been founded in 1993 by Alan Sked, but initially had only very limited success. Due to a change in the election principle, the European Parliament election, 1999 allowed for the first UKIP parliamentary representation. Many commentators [33] believe over-interest in the issue to be an important reason why the Conservative Party lost the General Election of 2001. They argue that the British electorate was more influenced by domestic issues than by European affairs.

After the electoral defeat of the UK Conservatives in 2001, the issue of Eurosceptism was important in the contest to elect a new party leader. The winner, Iain Duncan Smith, was seen as more Eurosceptic than his predecessor, William Hague. As opposition leader, Iain Duncan Smith attempted to disaffiliate the British Conservative Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) from the federalist European People's Party group. As MEPs must participate in a transnational alliance to retain parliamentary privileges, Duncan Smith sought the merger of Conservative MEPs into the Eurosceptic Union for a Europe of Nations (UEN) group. Conservative MEPs vetoed this move because of the presence within the UEN of representatives of neo-fascist parties who do not share similar domestic politics. In 2004, Duncan Smith's successor, Michael Howard, emphasised that Conservative MEPs would remain in the EPP Group so as to maintain influence in the European Parliament. However Michael Howard's successor David Cameron pledged to remove Conservative MEPs from the EPP Group and this has now been implemented.

UKIP received 16% of the vote and gained 12 MEPs in the 2004 European Election. The party's results improved in the 2009 UK European Election, coming in second, above the incumbent Labour Party.[34] In the 2014 European Parliament elections UKIP support reached a new high water mark, coming first ahead of the Labour party, and gaining 26.6% of the vote

Eurosceptic political parties

The different voting systems allowed some UK political parties with low amount of direct elected MPs in London to gain representation in the European Parliament, including the United Kingdom Independence Party. Smaller parties and electoral alliances have included the Referendum Party, Alliance for Democracy (UK), We Demand a Referendum, which was launched by Nikki Sinclaire, a former UKIP MEP in June 2012.[35]

Senior figures in both the Labour Party and Conservative Party have held strongly contrasting views on European integration ever since it became a contentious issue back in the 1970s. Neither party currently advocates the formal withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EU, although both have put forward proposals for the reform of European institutions.

The conservative party faced strong rifts. Conservative governments took major political steps towards a stronger integration of Britain in Europe but had to placate anti-European sentiment in the political base and the conservative media as well. After 1945, Winston Churchill was an early supporter of pan-Europeanism[36] and called for a "United States of Europe" and the creation of a "Council of Europe".[36] He participated in the Hague Congress of 1948, which discussed the future structure and role of this Council of Europe.[36] Churchill's landmark refusal to join the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1951 and his general sceptical feelings toward a British inside role in European integration's shaped the general British ambivalence towards all things Europe.

We have our own dream and our own task. We are with Europe, but not of it. We are linked but not combined. We are interested and associated but not absorbed.[37]

Pro-European reformers, as the Conservative former Foreign Secretary Sir Malcolm Rifkind took to draw lines against a European superstate.[38]

The Liberal Democrats, the UK's third-largest parliamentary party, are strongly pro-EU but advocate institutional reform to advance European federalism, with a greater role for national parliaments in scrutinising EU legislation though with less power (through the raising of Qualified Majority Voting blocking thresholds as in the Lisbon Treaty) to block or amend it.

The Scottish National Party (SNP) has tended to be pro-EU since the 1980s. The SNP's heartlands tend to be in fishing and farming areas of Scotland. However these regions tended in the Scottish independence referendum for remaining in the Union with Britain (and the EU), against the SNP proposition. Scottish farmers received £583 million in subsidy payments from the EU under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) alone in 2013.[39]

A "left and labour movement approach" to Euroscepticism (launched by the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers (RMT), the Communist Party of Britain) is No2EU.[40]

The Green Party of England and Wales does not seek to remove the United Kingdom from the European Union, but supports another referendum on the country's membership and is also highly critical of some aspects of the EU.

Opinion polling

The assessment of attitudes to the European Union and European Parliamentary Election voting intentions is undertaken on a regular basis by a variety of opinion polling organisations, including ComRes, ICM, Populus and Survation. For detailed polls see Proposed referendum on United Kingdom membership of the European Union

Support for withdrawal

According to an Opinium/Observer poll taken in 20 February 2015, 51% of the British electorate said they wanted the United Kingdom to leave the European Union if they were offered a referendum, whereas 49% would not. These studies also showed that 41% of the electorate view the EU as a positive force overall, whereas 34% saw it as negative,[41] and a study in November 2012 showed that while 48% of EU citizens trust the European Parliament, only 22% of the UK trusted the Parliament.[42]:110–2: QA 14.1

However, support and opposition for withdrawal from the EU are not evenly distributed among the different age groups: opposition to EU membership is most prevalent among those 60 and older, with a poll from 22–23 March 2015 showing that 48% of this age group oppose EU membership. This decreases to 22% among those aged 18–24 (with 56% of 18-24 year olds stating that they would vote for Britain to remain in the EU). Finally, the results of the poll showed some regional variation: support for withdrawal from the EU is lowest in Scotland and London (at 22% and 32% respectively) but reaches 42% in the Midlands and Wales (the only region polled with a plurality in favour of withdrawal).[43]

The February 2015 study also showed that trust of the UK's relationship with the EU is split along partisan lines: 35% trusted the Tories (Conservatives); 33% trusted Labour; 15% trusted UKIP; 7% trusted the Greens and 6% trusted the Lib Dems.[41]

2015

| Date(s) conducted | stay | leave | Unsure | Sample | Held by | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24–26 March | 49% | 44% | 7% | 1,007 | Panelbase | Northern Ireland not sampled |

| 22–23 March | 46% | 36% | 15% | 1,641 | YouGov/The Sun | Northern Ireland not sampled |

| 18–23 March | 42% | 34% | 20% | 8,271 | YouGov/The Times | Northern Ireland not sampled |

| 23–24 February | 45% | 37% | 13% | 1,520 | YouGov Eurotrack | Northern Ireland not sampled |

| 22–23 February | 45% | 35% | 17% | 1,772 | YouGov/The Sun | Northern Ireland not sampled |

| 17–20 February | 41% | 44% | 14% | 1,975 | Opinium/Observer | Northern Ireland not sampled |

| 25–26 January | 43% | 37% | 14% | 1,656 | YouGov/The Sun | Northern Ireland not sampled |

| 18–19 January | 43% | 38% | 15% | 1,747 | YouGov/British Influence | Northern Ireland not sampled |

| 15–19 January | 38% | 34% | 23% | 1,188 | TNS-BMRB | Northern Ireland not sampled |

| 6–8 January | 37% | 40% | 18% | 1,201 | TNS-BMRB | Northern Ireland not sampled |

See also

- Proposed referendum on United Kingdom membership of the European Union

- Commission Regulation (EC) No 2257/94 (straight bananas)

- Factortame litigation

- Metric Martyrs

References

- ↑ "Winston Churchill speaking in Zurich, I9 September 1946".

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Watts, Duncan; Pilkington, Colin (2005). Britain in the European Union Today (3rd ed.). Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719071799.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Gehler, Michael (2009). From Common Market to European Union Building. Vienna: Böhlau. p. 240. ISBN 9783205777441.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 This Blessed Plot: Britain and Europe from Churchill to Blair, Hugo Young, Overlook Press, 1998

- ↑ Britain in the European Union Today: Third Edition, Duncan Watts, Colin Pilkington, Manchester University Press, 29.11.2005, p.220

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Anti-Europeanism and Euroscepticism in the United States, Patrick Chamorel No 25, EUI-RSCAS Working Papers from European University Institute (EUI), Robert Schuman Centre of Advanced Studies (RSCAS) 2004

- ↑ Culture of Fascism: Visions of the Far Right in Britain, Julie V. Gottlieb, Thomas P. Linehan.B.Tauris, 31.12.2003, p.75

- ↑ DRÁBIK, Jakub. Oswald Mosley´s Concept of a United Europe. A Contribution to the Study of Pan-European Nationalism. In. The Twentieth Century, 2/2012, s. 53-65, Prague : Charles University in Prague, ISSN 1803-750X

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Drawn into the Heart of Europe?: Die britische Europapolitik im Spiegel von Karikaturen (1973-2008), Julia Quante, LIT Verlag Münster, 2013

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 From common market to European Union building, Michael Gehler, Böhlau Verlag Wien, 2009

- ↑ Winnett, R. & Waterfield, B. (31 March 2011). "£300 a year: the cost to each taxpayer of funding EU". London: The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ↑ "EU 'democracy' and why we always lose as its relentless expansion continues". London: Daily Mail. 18 November 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- ↑ Castle, Stephen (26 May 2005). "Barroso survives confidence debate over free holiday with Greek tycoon". The Independent (London). Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ Castle, Stephen (26 May 2005). The Independent (London) http://news.independent.co.uk/europe/article223215.ece. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Hannan, Daniel (14 November 2007). "Why aren't we shocked by a corrupt EU?". The Daily Telegraph (London). Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ Why we should leave: The top Ten reasons we would be BETTER OFF OUT ...

- ↑ "Your favourite Conference Clips". BBC. 3 October 2007. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ↑ Lieber, R. J. (1970). British politics and European unity: parties, elites, and pressure groups. University of California Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-520-01675-0.

- ↑ "Labour MPs launch anti-euro drive", BBC News, 10 April 2002

- ↑ Patrick Wintour "TUC accuses Tory Eurosceptics of trying to undermine labour law", The Guardian, 16 January 2013

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Peter Oborne "It’s taken decades, but Labour has seen the light on Europe", telegraph.co.uk, 21 April 2011

- ↑ Daniel Knowles "Labour's new Euroscepticism should worry the Coalition", telegraph.co.uk, 4 November 2011

- ↑ Pax Anglo-Americana, Ursula Lehmkuhl, Oldenbourg 1999, p.236

- ↑ Peter Oborne "David Cameron may have finished off the Tories – but he had no choice", Daily Telegraph, 23 January 2013

- ↑ Simon Heffer Like the Roman: The Life of Enoch Powell, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1998, p.707-10

- ↑ "1975: Labour votes to leave the EEC". BBC News. 26 April 1975. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ "Political Science Resources: politics and government around the world". Psr.keele.ac.uk. 5 May 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ↑ "Political Science Resources: politics and government around the world". Psr.keele.ac.uk. 5 May 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Reuters (16 December 2005). "Reuters footage". ITN Source archive. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

Blair is under pressure to yield on the rebate won by his predecessor Margaret Thatcher in 1984 to reflect the fact that Britain, then the EU's second poorest member, benefited little from farm subsidies.

- ↑ Katwala, Sunder (12 September 2007). "Bring Back Social Europe". London: guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 4 September 2008.

- ↑ "30 October 1990: 'No! No! No!'", BBC Democracy Live, 31 October 2009

- ↑ Charles C. W. Cooke "How Thatcher Came to Be Euroskeptic", National Review, 23 July 2012

- ↑ "Tories facing identity crisis". CNN. 8 June 2001. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ "European Election Results 2009, UK Results". BBC News. 19 April 2009. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ Richards, S. (September 20, 2012). "Is it time for UKIP to make way for a new Eurosceptic party?". Daily Mail. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

You can tell when it's UKIP Conference time, because Nikki Sinclaire, the former UKIP MEP, can always be relied upon to pull a stunt to try to steal the limelight from her old party. This time, she's set up her own party, the "We Demand A Referendum Party".

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Jenkins, p. 810 and p. 819-14how can this be 819-[8]14?

- ↑ "Remembrance Day 2003". Churchill Society London. Retrieved 2007-04-25.

- ↑ "Rifkind looks to partnership of nations as solution for Europe". The Herald (newspaper). 24 Jan 1997. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ Bicker, Laura (29 April 2014). "Scottish independence: Farmers give their views on referendum debate". BBC. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ↑ "Communists plan for EU elections". Morning Star (People's Press Printing Society). 25 May 2013. Archived from the original on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Boffey, Daniel (21 February 2015). "Majority of electorate would vote for UK to leave EU in latest poll". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ↑ "Standard Eurobarometer 71 Table of Results, Standard Eurobarometer 71: Public Opinion in the European Union (fieldwork June — July 2009)" (PDF). European Commission. September 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ↑ "YouGov Survey Results" (PDF). YouGov. 22–23 March 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2015.