Euclid's lemma

In number theory, Euclid's lemma is a lemma that captures a fundamental property of prime numbers, namely: If a prime divides the product of two numbers, it must divide at least one of those numbers. It is also called Euclid's first theorem[1][2] although that name more properly belongs to the side-angle-side condition for showing that triangles are congruent.[3] For example, 133 × 143 = 19019, and since 19019 is divisible by 19, the lemma implies that one or both of 133 or 143 must be as well. In fact, 133 ÷ 19 = 7.

This property is the key[4] in the proof of the fundamental theorem of arithmetic. It is used to define prime elements, a generalization of prime numbers to arbitrary commutative rings.

The lemma is not true for composite numbers. For example, 4 does not divide 6 and 4 does not divide 10, yet 4 does divide their product, 60.

Formulations

Let p be a prime number, and assume p divides the product of two integers a and b. (In symbols this is written p|ab. Its negation, p does not divide ab is written p∤ab.)

Then p|a or p|b (or both).

Equivalent statements are

If p∤a and p∤b, then p∤ab.

If p∤a and p|ab, then p|b.

A generalization is also called Euclid's lemma:

If n|ab, and n is relatively prime to a, then n|b.

This is a generalization because if n is prime, either

- n|a or

- n is relatively prime to a. In this second possibility, n∤a so n|b.

History

The lemma first appears as proposition 30 in Book VII of Euclid's Elements. It is included in practically every book that covers elementary number theory.[5][6][7][8][9]

Proof via Bézout's identity

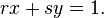

The usual proof involves another lemma called Bézout's identity. This states that if x and y are relatively prime integers (i.e. they share no common divisors other than 1) there exist integers r and s such that

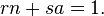

Let a and n be relatively prime, and assume that n | ab. By Bézout, there are r and s making

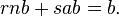

Multiply both sides by b:

The first term on the left is divisible by n, and the second term is divisible by ab which by hypothesis is divisible by n. Therefore their sum, b, is also divisible by n. This is the generalization of Euclid's lemma mentioned above.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Bajnok, Béla (2013), An Invitation to Abstract Mathematics, Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer, Theorem 14.5, ISBN 9781461466369.

- ↑ Joyner, David; Kreminski, Richard; Turisco, Joann (2004), Applied Abstract Algebra, JHU Press, Proposition 1.5.8, p. 25, ISBN 9780801878220.

- ↑ Martin, G. E. (2012), The Foundations of Geometry and the Non-Euclidean Plane, Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer, p. 125, ISBN 9781461257257.

- ↑ In general, to show that a domain is a unique factorization domain, it suffices to prove Euclid's lemma and ACCP.

- ↑ Gauss, DA, Art. 14

- ↑ Hardy & Wright, Thm. 3

- ↑ Ireland & Rosen, prop. 1.1.1

- ↑ Landau, Thm. 15

- ↑ Riesel, Thm. A2.1

References

The Disquisitiones Arithmeticae has been translated from Latin into English and German. The German edition includes all of his papers on number theory: all the proofs of quadratic reciprocity, the determination of the sign of the Gauss sum, the investigations into biquadratic reciprocity, and unpublished notes.

- Gauss, Carl Friedrich; Clarke, Arthur A. (translator into English) (1986), Disquisitiones Arithemeticae (Second, corrected edition), New York: Springer, ISBN 0387962549

- Gauss, Carl Friedrich; Maser, H. (translator into German) (1965), Untersuchungen uber hohere Arithmetik (Disquisitiones Arithemeticae & other papers on number theory) (Second edition), New York: Chelsea, ISBN 0-8284-0191-8

- Hardy, G. H.; Wright, E. M. (1980), An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers (Fifth edition), Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0198531715

- Ireland, Kenneth; Rosen, Michael (1990), A Classical Introduction to Modern Number Theory (Second edition), New York: Springer, ISBN 0-387-97329-X

- Landau, Edmund (1966), Elementary Number Theory, New York: Chelsea

- Riesel, Hans (1994), Prime Numbers and Computer Methods for Factorization (second edition), Boston: Birkhäuser, ISBN 0-8176-3743-5