Ethyl carbamate

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Ethyl carbamate | |

| Other names

Urethane | |

| Identifiers | |

| 3DMet | B00312 |

| 51-79-6 | |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:17967 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL462547 |

| ChemSpider | 5439 |

| DrugBank | DB04827 |

| EC number | 200-123-1 |

| |

| Jmol-3D images | Image Image |

| KEGG | C01537 |

| MeSH | Urethane |

| PubChem | 5641 |

| RTECS number | FA8400000 |

| |

| UNII | 3IN71E75Z5 |

| UN number | 2811 |

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula |

C3H7NO2 |

| Molar mass | 89.09 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | White crystals |

| Density | 1.056 g cm−3 |

| Melting point | 46 °C (115 °F; 319 K) |

| Boiling point | 182 °C (360 °F; 455 K) |

| 0.480 g cm−3 at 15 °C | |

| log P | -0.190(4) |

| Vapor pressure | 1.3 kPa at 78 °C |

| Acidity (pKa) | 13.58 |

| Dipole moment | 0.5206015862 D |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed May cause cancer |

| EU Index | 607-149-00-6 |

| EU classification | |

| R-phrases | R45 |

| S-phrases | S45, S53 |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Flash point | 92 °C (198 °F; 365 K) |

| Except where noted otherwise, data is given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C (77 °F), 100 kPa) | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

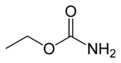

Ethyl carbamate (also called urethane) is a chemical compound with the molecular formula C3H7NO2 first prepared in the nineteenth century. Structurally, it is an ester of carbamic acid. Despite its common name, it is not a component of polyurethanes.

Synthesis

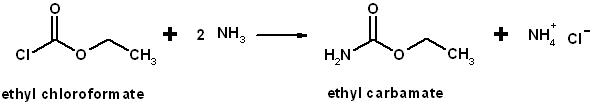

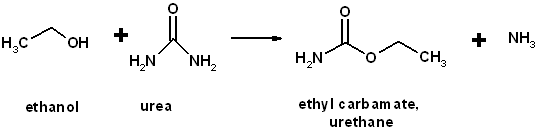

Ethyl carbamate is a white crystalline substance produced by the action of ammonia on ethyl chloroformate or by heating urea nitrate and ethyl alcohol:[1]

Uses

Ethyl carbamate has been produced commercially in the United States for many years. It has been used as an antineoplastic agent and for other medicinal purposes but this ended after it was discovered to be carcinogenic in 1943. However, Japanese usage in medical injections continued and from 1950 to 1975 an estimated 100 million 2 ml ampules of 7 to 15% solutions of ethyl carbamate were injected into patients as a co-solvent in water for dissolving water-insoluble analgesics used for post-operation pain. These doses were estimated by Nomura (Cancer Research, 35, 2895–2899, October 1975) to be at levels that are carcinogenic in mice. This practice was stopped in 1975. "This regrettable medical situation appears to have involved the largest number (millions) of humans exposed to the largest doses of a pure carcinogen that is on record" (Japanese Journal of Cancer Research, 82, 1323–1324, December 1991). The author, U.S. cancer researcher James A. Miller, called for studies to determine the effects on Japanese cancer rates to be performed but apparently none were ever done.

Prior to World War II, ethyl carbamate saw relatively heavy use in the treatment of multiple myeloma before it was found to be toxic, carcinogenic and largely ineffective.[2] By US FDA regulations, ethyl carbamate has been withdrawn from pharmaceutical use. However, small quantities of ethyl carbamate are also used in laboratories as an anesthetic for animals.[3]

Ethyl carbamate was upgraded to a Group 2A carcinogen by IARC in 2007.

Formerly, crosslinking agents for permanent press textile treatments were synthesized from ethyl carbamate.[4]

Occurrence in beverages and food

The discovery of the widespread presence of ethyl carbamate in alcoholic beverages first occurred during the mid-1980s. To raise public awareness of this issue, the U.S. Center for Science in the Public Interest published, in 1987, Tainted Booze: The Consumer's Guide to Urethane in Alcoholic Beverages. Studies have shown that most, if not all, yeast-fermented alcoholic beverages contain traces of ethyl carbamate (15 ppb to 12 ppm).[5] Other foods and beverages prepared by means of fermentation also contain ethyl carbamate. For example, bread has been found to contain 2 ppb;[6] as much as 20 ppb has been found in some samples of soy sauce.[7] Amounts of both ethyl carbamate and methyl carbamate have also been found in wines, sake, beer, brandy, whiskey and other fermented alcoholic beverages.

It has been shown that ethyl carbamate forms from the reaction of ethanol with urea:

This reaction occurs much faster at higher temperatures, and therefore higher concentrations of ethyl carbamate are found in beverages that are heated during processing, such as brandy, whiskey, and other distilled beverages. Additionally, heating after bottling either during shipping or in preparation will cause ethyl carbamate levels to rise further.

The urea in wines results from the metabolism of arginine or citrulline by yeast or other organisms. The urea waste product is initially metabolised inside the yeast cell until it builds up to a certain level. At that point, it is excreted externally where it is able to react with the alcohol to create ethyl carbamate.

In 1988, wine and other alcoholic beverage manufacturers in the United States agreed to control the level of ethyl carbamate in wine to less than 15 ppb (parts per billion), and in stronger alcoholic drinks to less than 125 ppb.[5]

Although the urea cannot be eliminated, it can be minimized by controlling the fertilization of grape vines, minimizing their heat exposure, using self-cloning yeast[8] and other actions.[9] Furthermore, some strains of yeast have been developed to help reduce ethyl carbamate during commercial production of alcoholic beverages.[10]

Another important mechanism for ethyl carbamate formation in alcoholic beverages is the reaction from cyanide as precursor, which causes comparably high levels in spirits derived from cyanogenic plants (i.e. predominantly stone-fruit spirits and cachaca).[11]

Hazards

Ethyl carbamate is not acutely toxic to humans, as shown by its use as a medicine. Acute toxicity studies show that the lowest fatal dose in rats, mice, and rabbits equals 1.2 grams/kg or more. When ethyl carbamate was used medicinally, about 50 percent of the patients exhibited nausea and vomiting, and long time use led to gastroenteric hemorrhages.[12] The compound has almost no odor and a cooling, saline, bitter taste.[13]

Studies with rats, mice, and hamsters has shown that ethyl carbamate will cause cancer when it is administered orally, injected, or applied to the skin, but no adequate studies of cancer in humans caused by ethyl carbamate has been reported due to the ethical considerations of such studies.[14] However, in 2007, the International Agency for Research on Cancer raised ethyl carbamate to a Group 2A carcinogen that is "probably carcinogenic to humans," one level below fully carcinogenic to humans. IARC has stated that ethyl carbamate can be “reasonably anticipated to be a human carcinogen based on sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in experimental animals.”[15] In 2006, the Liquor Control Board of Ontario in Canada rejected imported cases of sherry due to excessive levels of ethyl carbamate.

Alcoholic beverages, particularly certain stone-fruit spirits and whiskies, tend to contain much higher concentrations of urethane. Heating (e.g., cooking) the beverage increases the ethyl carbamate content, and some concern exists over shipping wines to overseas markets in containers that tend to overheat. In addition, urethane has a tendency to accumulate in the human body from a number of daily dietary sources, e.g., alcohols, bread and other fermented grain products, soy sauce, orange juice and commonly consumed foods. Hence, exposure risk to human health is increasingly evaluated on the total ethyl carbamate intake from the daily diet (WHO refers to this as "margin of exposure" or MOE), of which alcoholic beverages often provide the most significant portion.

Studies in Korea (2000) and Hong Kong (2009) outline the extent of the accumulative exposure to ethyl carbamate in daily life. Fermented foods such as soy sauce, kimchi, soybean paste, breads, rolls, buns, crackers and bean curd, along with wine, sake and plum wine, were found to be the foods with the highest ethyl carbamate levels in traditional Asian diets.

In 2005, the JECFA (Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee On Food Additives) risk assessment evaluation of ethyl carbamate concluded that the MOE intake of ethyl carbamate from daily food and alcoholic beverages combined is of concern and mitigation measures to reduce ethyl carbamate in some alcoholic beverages should continue. There is little doubt that ethyl carbamate in alcoholic beverages is very important to health authorities, while the cumulative daily exposure in the typical diet is also an issue of rising concern that merits closer observation. The Korean study concluded, "It would be desirable to closely monitor ethyl carbamate levels in Korean foods and find ways to reduce the daily intake."

The IARC evaluation has led to the following US regulatory actions:

- NESHAP: Listed as a Hazardous Air Pollutant (HAP)

- Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act: Reportable Quantity (RQ) = 100 lb

- Emergency Planning and Community Right-To-Know Act, EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory: A listed substance subject to RCRA reporting requirements

- RCRA Listed Hazardous Waste: substance - U238

Detection in alcoholic beverages

The concerns raised by the toxicological aspects of EC together with the low concentration levels (µg/L) found in wines, as well as the occurrence of interferences on detection, has motivated several researchers to develop new methods to determine it in wines. Several extraction and chromatographic techniques have been used, including continuous liquid–liquid extraction (LLE) with Soxhlet apparatus, derivatization with 9-xanthydrol followed by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with fluorescence detection and even LLE after derivatization, followed by gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry detection(GC–MS). On the other hand, the reference method set by the International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV) uses solid phase extraction (SPE) preceding GC–MS quantification. Other methods also make use of SPE, but use gas chromatography with mass spectrometry (MDGC/MS) and liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) for detection. Most of the methodologies found in the literature to quantify EC use gas chromatography, using LLE and SPE as extraction techniques. Nevertheless, several efforts have also been done to develop new methodologies to determine EC without using long procedures and hard-working analyses, combining precision to high sensitivity. In this regard, headspace solid phase microextraction (HS-SPME) has been gaining great highlighting and alternative methodologies has been proposed using the most recent identification and quantification technology, such as gas chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry detection (GC–MS/MS) and two-dimensional gas chromatography with time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC × GC–ToFMS).

Microextraction by packed sorbent (MEPS) has also becoming emergent, arising as a feasible and easy-to-use extraction technique. Recently a simple and sensitive methodology was developed and optimized to quantify EC in wines using MEPS extraction, through a hand-held automated analytical syringe, with GC–MS detection. MEPS/GC–MS methodology is an excellent tool to quantify EC in wines, gathering efficiency and effectiveness, without using long and hard-working procedures. [16] [17]

Related compounds

Other carbamates include methyl carbamate (urethylane, m. p. 52-54 °C),[18] butyl carbamate,[19] and phenyl carbamate (m. p. 149-152 °C),[20] which can also be prepared from the corresponding chloroformate and ammonia. These esters are white, crystalline solids at room temperature. Except for the phenyl carbamate, they sublime at moderate temperatures; methyl carbamate sublimes at room temperatures. The first two and ethyl carbamate are very soluble in water, benzene, and ether.[13][18][19] These other carbamates (methyl, butyl, and phenyl) are only used in small quantities for research purposes.

See also

References

- ↑ The Merck Index, 11th Edition, 9789

- ↑ Holland, JR; Hosley, H; Scharlau, C; Carbone, PP; Frei, E, 3rd; Brindley, CO; Hall, TC; Shnider, BI; Gold, GL; Lasagna, L; Owens, AH, Jr; Miller, SP (1966). "A controlled trial of urethane treatment in multiple myeloma". Blood 27 (3): 328–42. PMID 5933438.

- ↑ Virginia Commonwealth University, The Chemical/Biological Safety Section (CBSS) of the Office of Environmental Health and Safety, Working with Urethane, 2006. Accessed May 13, 2006

- ↑ NTP National Toxicology Program, NIEHS, National Institutes of Health, Eleventh Report on Carcinogens, Urethane, 2005. Accessed May 13, 2006

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Segal, M Too Many Drinks Spiked with Urethane, US Food and Drug Administration, September 1988

- ↑ Haddon W F, M I Mancini, M Mclaren, A Effio, L A Harden, R I Egre, & J L Bradford (1994). Cereal Chemistry 71 (2): 207–215. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Matsudo T, T Aoki, K Abe, N Fukuta, T Higuchi, M Sasaki & K Uchida (1993). "Determination of ethyl carbamate in soy sauce and its possible precursor". J Agric Food Chem 41 (3): 352–356. doi:10.1021/jf00027a003.

- ↑ American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 57 (2): 113–124. 2006. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Butzke, C E & L F Bisson, Ethyl Carbamate Preventative Action Manual, Depart. of Viticulture & Enology, U. of CA, Davis, CA, for US FDA, 1997 accessed May 13, 2006

- ↑ http://www.ec.gc.ca/subsnouvelles-newsubs/default.asp?lang=En&n=AECC21AD-1

- ↑ Lachenmeier DW, Lima MC, Nóbrega IC, Pereira JA, Kerr-Corrêa F, Kanteres F, Rehm J. (2010). "Cancer risk assessment of ethyl carbamate in alcoholic beverages from Brazil with special consideration to the spirits cachaça and tiquira". BMC Cancer 10: 266. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-10-266. PMC 2892455. PMID 20529350.

- ↑ Office of Toxic Substances, “Chemical Hazard Information Profile Urethane, CAS No. 51-79-6 , U.S. EPA, Washington, D.C., 12 pages, 26 references, 1979, accessed May 13, 2006 at http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 National Library of Medicine, Hazardous Data Bank, Ethyl Carbamate 2006a, accessed May 13, 2006 at http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/

- ↑ IARC, 1974

- ↑ NTP 2005

- ↑ Leça, J. M., V. Pereira, A. C. Pereira and J. C. Marques (2014). "Rapid and sensitive methodology for determination of ethyl carbamate in fortified wines using microextraction by packed sorbent and gas chromatography with mass spectrometric detection." Analytica Chimica Acta 811(0): 29-35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2013.12.018

- ↑ Weber, J. V. and V. I. Sharypov (2009). "Ethyl carbamate in foods and beverages: a review." Environmental Chemistry Letters 7(3): 233-247.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 National Library of Medicine, Hazardous Data Bank, Methyl Carbamate 2006b, accessed May 13, 2006 at http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 National Library of Medicine, Hazardous Data Bank, Butyl Carbamate 2006c, accessed May 13, 2006 at http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov

- ↑ Dean, JA (editor), Lange’s Handbook of Chemistry, 13th Ed., 1985, p. 7-586, #p191.

External links

- NLM Hazardous Substances Databank – Ethyl carbamate

- Urethane in the ChemIDplus database