Eta Carinae

Eta Carinae and Carina Nebula in the constellation of Carina | |

| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Carina |

| Right ascension | 10h 45m 03.591s[1] |

| Declination | −59° 41′ 04.26″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | −0.8 to 7.9[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | F:I_pec_e[3] / O[4][5] |

| U−B color index | -0.45[6] |

| B−V color index | 0.61[6] |

| V−R color index | 1.31[6] |

| R−I color index | 0.49[6] |

| J−H color index | 0.88[6] |

| J−K color index | 2.45[6] |

| Variable type | LBV[2] & binary |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −25.0[7] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −7.6[1] mas/yr Dec.: 1.0[1] mas/yr |

| Distance | 7,500 ly (2,300[8] pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | -8.6 (2012)[9] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 120 / 30[10] M☉ |

| Radius | ~240[11] / 24[4] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 5,000,000 / <1,000,000[4][5] L☉ |

| Temperature | 9,400[12] / 37,200[4] K |

| Age | <3 × 106[5] years |

| Orbit | |

| Primary | Eta Carinae A |

| Companion | Eta Carinae B |

| Period (P) | 2,022.7 days[13] (5.54 yr) |

| Semi-major axis (a) | 15.4[14] AU |

| Eccentricity (e) | 0.9[15] |

| Inclination (i) | 130-145[14]° |

| Periastron epoch (T) | 2009.03[16] |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

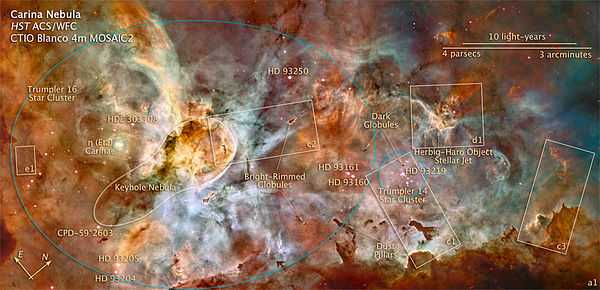

Eta Carinae (η Carinae or η Car), formerly known as Eta Argus, is a stellar system containing at least two stars, about 7,500 light-years (2,300 parsecs) from the Sun in the direction of the constellation Carina. It is a member of the Trumpler 16 open cluster within the much larger Carina Nebula. The system currently has a combined luminosity of over five million times the Sun's.[12]

Eta Carinae is circumpolar south of latitude 30°S, but is never visible north of latitude 30°N. It was first recorded as a 4th magnitude star, before brightening considerably over the period 1837 to 1856—in an event known as the Great Eruption. Eta Carinae became the second brightest star in the sky between 11 and 14 March 1843 before fading well below naked eye visibility. It has brightened consistently since about 1940, to magnitude 4.6 as of 2012.

The two main stars of the Eta Carinae system revolve in an eccentric orbit every 5.54 years. The primary is a peculiar star similar to a luminous blue variable (LBV) that initially had around 150 solar masses and has lost at least 30. Because of its mass and the stage of its life, it is expected to explode as a supernova or hypernova in the astronomically near future. This is currently the only star known to emit natural LASER light in ultraviolet wavelengths.[20] The secondary is a hot star, probably of spectral class O, around 30 times as massive as the Sun and is itself a highly luminous star. The system is heavily obscured by the Homunculus Nebula, material ejected from the primary during its Great Eruption in the 19th century.

Observational history

Discovery and naming

There is no reliable evidence of Eta Carinae being observed or recorded before the 17th century, although Dutch navigator Pieter Keyser described a fourth magnitude star at approximately the correct position around 1595-96, which was copied onto the celestial globes of Petrus Plancius and Jodocus Hondius and the 1603 Uranometria of Johann Bayer. However, Frederick de Houtman's catalogue from 1603 does not include Eta Carinae among the other fourth magnitude stars in the region. The earliest firm record was made by Edmond Halley in 1677 when he recorded the star simply as Sequens (i.e. "following" relative to another star) within a new constellation Robur Carolinum. His Catalogus Stellarum Australium was published in 1679. The star was also known by the Bayer designations Eta Roboris Caroli, Eta Argus or Eta Navis.[21] In 1751 Nicolas Louis de Lacaille mapped the stars of Argo Navis and Robur Carolinum into separate smaller constellations. The star was placed within the keel portion of the ship named as the new constellation Carina, gaining the name Eta Carinae.[22]

Brightness

.png)

Halley gave an approximate apparent magnitude of "4" at the time of discovery, which has been calculated as magnitude 3.3 on the modern scale. The handful of possible earlier sightings suggest that Eta Carinae was not significantly brighter than this for much of the 17th century.[21]

Further sporadic observations over the next 70 years show that Eta Carinae was probably around or below 4th magnitude, until Lacaille recorded it at 2nd magnitude in 1751.[22] It is unclear whether Eta Carinae varied significantly in brightness over the next 50 years, with occasional observations such as William Burchell at 4th magnitude in 1815, but it is uncertain whether these are just re-recordings of earlier observations. In 1827 Burchell specifically noted its unusual brightness at 1st magnitude, and was the first to suspect that it varied in brightness.[21] John Herschel made a detailed series of accurate measurements in the 1830s showing Eta Carinae consistently around magnitude 1.4 until November 1837. On the evening of December 16, Herschel was astonished to see that it had brightened to just outshine Rigel.[23] This event marked the beginning of a roughly 18 year period known as the Great Eruption.[21]

Eta Carinae was brighter still on January 2, 1838, equivalent to Alpha Centauri, before fading slightly over the following three months. Herschel did not observe the star after this, but received correspondence from the Reverend W.S. Mackay in Calcutta, who wrote in 1843, "To my great surprise I observed this March last (1843), that the star Eta Argus had become a star of the first magnitude fully as bright as Canopus, and in colour and size very like Arcturus." Observations at the Cape of Good Hope indicated it peaked in brightness, surpassing Canopus, over March 11 to 14 1843 before beginning to fade, then brightening to between the brightness of Alpha Centauri and Canopus between March 24 and 28 before fading.[23] For much of 1844 the brightness was mid-way between Alpha Centauri and Beta Centauri, around magnitude +0.2, before brightening again at the end of the year. At its brightest in 1843 it likely reached an apparent magnitude of -0.8, then -1.0 in 1845.[9]

The peaks in 1827, 1838, and 1843 may have been related to the periastron passage of the binary orbit.[24] From 1845 to 1856, the brightness decreased by around 0.1 magnitudes per year, but with possible rapid and large fluctuations.[9] In 2010, astronomers Duane Hamacher and David Frew from Macquarie University in Sydney showed that the Boorong people of northwestern Victoria, Australia, witnessed the outburst of Eta Carinae in the 1840s and incorporated it into their oral traditions as Collowgulloric War, the wife of War (Canopus, the Crow – wɑː).[25]

From 1857 the brightness decreased rapidly until it faded below naked eye visibility by 1886. This has been calculated to be due to the condensation of dust in the ejected material surrounding the star rather than an intrinsic change in luminosity.[26] There was a brightening from 1887 to 1895, peaking at about magnitude 6.2 then dimming rapidly to about magnitude 7.5. This appeared to be a smaller copy of the Great Eruption, expelling material that formed the Little Homunculus and Weigelt Blobs.[27][28]

Between 1900 and at least 1940, Eta Carinae appeared to have settled at a constant brightness at around magnitude 7.6,[21] but in 1953 it was noted to have brightened again to magnitude 6.5.[29] The brightening continued steadily, but with fairly regular variations of a few tenths of a magnitude that were later identified as having a 5.54 year period.[24] A sudden doubling of brightness was observed in 1998–1999 bringing it back to naked eye visibility. As of 2012, the visual magnitude was 4.6.[30] The brightness does not always vary consistently at different wavelengths, and does not always consistently follow the 5.5 year cycle.[5][31]

Spectrum

The spectrum of Eta Carinae is peculiar and variable. The earliest observations of the star's spectrum in 1893 are described as similar to an F5 star, but with a few emission lines. Analysis to modern spectral standards suggests an early F spectral type.[32] By 1895, the spectrum consisted mostly of strong emission lines, with the absorption lines present but largely obscured by emission. The lines vary greatly in width and profile.[33][34]

Direct spectral observations did not begin until after the Great Eruption, but light echoes from the eruption were detected using the U.S. National Optical Astronomy Observatory's Blanco 4-meter telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory. Analysis of the reflected spectra indicated the light was emitted when Eta Carinae had the appearance of a 5,000 K G2-to-G5 supergiant, some 2,000 K cooler than expected from other supernova impostor events.[35] Further light echo observations show that following the peak brightness of the Great Eruption the spectrum developed prominent P Cygni profiles and CN molecular bands. These indicate that the star, or the expanding cloud of ejected material, had cooled further and may have been colliding with circumstellar material in a similar way to a type IIn supernova.[36]

In the second half of the 20th century, infra-red and ultra-violet spectra became available, as well as much higher resolution visual spectra. The spectrum continued to show complex and baffling features, with much of the energy from the central star being recycled into the infra-red by surrounding dust, some reflection of light from the star from dense localised objects in the circumstellar material, but with obvious high ionisation features indicative of very high temperatures. The line profiles are complex and variable, indicating a number of absorption and emission features at various velocities relative to the central star.[37][38]

Although the strength and profile of most spectral lines are highly variable, there are a number of distinctive features. The spectrum is dominated by emission lines, usually broad although the higher excitation lines are overlaid by a narrow central component. The narrow emission lines are from high excitation ionisation of dense nebulosity, especially the Weigelt Blobs. Most lines show a P Cygni profile but with the absorption wing much weaker than the emission. The broad P Cygni lines are typical of strong stellar winds, with very weak absorption in this case because the central star is so heavily obscured. Electron scattering wings are present but relatively weak. Hydrogen lines are present and strong, showing that Eta Carinae still retains much of its hydrogen envelope. HeI lines are much weaker than the hydrogen lines, and the absence of HeII lines provides an upper limit to the possible temperature of the primary star. NII lines can be identified but are not strong, while carbon lines cannot be detected and oxygen lines are at best very weak, indicating core hydrogen burning via the CNO cycle with some mixing to the surface. Perhaps the most striking feature is the rich FeII emission in both permitted and forbidden lines, with the forbidden lines arising from excitation of nebulosity around the star.[39][40]

The 5.5 year orbital cycle produces strong spectral changes at periastron that are known as spectroscopic events. Certain wavelengths of radiation suffer eclipses, either due to actual occultation by one of the stars, or due to passage within opaque portions of the complex stellar winds. Despite being ascribed to orbital rotation, these events vary significantly from cycle to cycle. These changes have become stronger since 2003 and it is generally believed that long-term secular changes in the stellar winds or previously ejected material may be the culmination of a return to the state of the star before its Great Eruption.[31][41][42]

High energy radiation

Several x-ray and gamma-ray sources have been detected around Eta Carinae, for example 4U 1037–60 in the 4th Uhuru catalogue and 1044–59 in the HEAO-2 catalog. The earliest detection of x-rays in the Eta Carinae region was from the Terrier-Sandhawk rocket, [43] followed by Ariel 5,[44] OSO 8,[45] and Uhuru[46] sightings.

More detailed observations were made with the Einstein Observatory,[47] ROSAT X-ray telescope,[48] Advanced Satellite for Cosmology and Astrophysics (ASCA),[49] and Chandra X-ray Observatory. There are multiple sources at various wavelengths right across the high energy electromagnetic spectrum: hard x-rays and gamma rays within 1 light-month of the Eta Carinae; hard x-rays from a central region about 3 light-months wide; a distinct partial ring "horse-shoe" structure in low energy x-rays 0.67 parsec (2.2 light-years) across corresponding to the main shockfront from the Great Eruption; diffuse x-ray emission across the whole area of the Homunculus; and numerous condensations and arcs outside the main ring.[50][51][52][53]

All the high energy emission associated with Eta Carinae varies during the orbital cycle. A spectroscopic minimum, or X-ray eclipse, occurred in July and August 2003 and similar events in 2009 and 2014 have been intensively observed.[54] The highest energy gamma-rays above 100 MeV detected by AGILE show strong variability, while lower energy gamma-rays observed by Fermi show little variability.[50][55]

Radio emission

Eta Carinae has been detected at various radio wavelengths including EHF (millimeter wave), SHF, and UHF. The detected radiation appears to be both thermal emission from warm gas and free-free emission from ionised gas. The free-free emission in particular varies during the orbital cycle, with significant dips during the periastron passage Spectroscopic events.[56][57]

Visibility

.jpg)

Currently (2014) a 4th magnitude star, Eta Carinae is comfortably visible to the naked eye in all but the most light-polluted skies in inner city areas.[58] However its brightness is variable over a wide range, from the second brightest star in the sky at one point in the 19th century to well below naked eye visibility. Its location at around 60°S in the far Southern Celestial Hemisphere means it cannot be seen by observers in Europe and much of North America.

Located between Canopus and the Southern Cross,[59] Eta Carinae is easily pinpointed as the brightest star within the large naked eye Carina Nebula, looking distinctly orange within the dark "V" dust lane.[60] In a telescope Eta Carinae is clearly non-stellar and high magnification will show the two orange lobes of the Homunculus Nebula on either side of a central core. Variable star observers can compare its brightness with several 4th and 5th magnitude stars closely surrounding the nebula.

Surroundings

Eta Carinae lies within the scattered stars of the Trumpler 16 open cluster. All the other members are well below naked eye visibility, although WR 25 is another extremely massive luminous star.[61] Trumpler 16 and its neighbour Trumpler 14 are the two dominant star clusters of the Carina OB1 association, an extended grouping of young luminous stars with a common motion through space.[62]

Eta Carinae is enclosed by—and lights up—a reflection nebula known as the Homunculus Nebula.[63] The Homunculus Nebula is composed mainly of dust which condensed from the debris ejected during the Great Eruption event in the mid-nineteenth century. The nebula consists primarily of two polar lobes aligned with the rotation axis of the star, plus an equatorial "skirt". Closer studies show many fine details: a Little Homunculus within the main nebula, probably formed by the 1890 eruption; a jet; fine streams and knots of material, especially noticeable in the skirt region; and three Weigelt Blobs—dense gas condensations very close to the star itself.[20][64]

Distance

The distance to Eta Carinae has been determined by several different methods, resulting in a widely accepted value of 2300 parsecs (7800 light-years), with a margin of error around 100 parsecs (330 light-years).[8] Too far away to have its distance directly measured using the parallax from the Earth's annual motion, Eta Carinae is also unsuitable due to surrounding nebulosity. However at least two stars expected to be at a similar distance are in the Hipparcos catalog. These are HD 93250 in Trumpler 16 and HD 93403, another member of Trumpler 16 or possibly of Trumpler 15. These two stars are assumed to be at approximately the same distance as Eta Carinae, all formed from the same molecular cloud, but the distances are too great for parallaxes to be reliable. HD 93250 and HD 93403 have recorded parallaxes of 0.53±0.42 milli-arcsec and 1.22±0.45 milli-arcsec respectively, suggesting distances of anywhere from 600 to 9,000 parsecs.[65]

The distances to star clusters can be estimated by using a Hertzsprung-Russell diagram or Color-color diagram to calibrate the absolute magnitudes of the stars, for example fitting the main sequence or identifying features such as a horizontal branch, and hence their distance from Earth. It is also necessary to know the amount of interstellar extinction to the cluster and this can be difficult in regions such as the Carina Nebula.[66] A distance of 2,250 parsecs has been determined from the calibration of O star luminosities in Trumpler 16.[67] After determining an abnormal reddening correction to the extinction, the distance to both Trumpler 14 and Trumpler 16 has been measured at 2900±300 parsecs.[68]

The known expansion rate of the Homunculus Nebula provides an unusual geometric method for measuring its distance. Assuming that the two lobes of the nebula are symmetrical, the projection of the nebula onto the sky depends on its distance. Values of 2.3, 2.25 and 2.3 kiloparsecs have been derived for the Homunculus, and Eta Carinae is clearly at the same distance.[8]

Properties

The Eta Carinae star system is currently one of the most massive that can be studied in great detail. Until recently Eta Carinae was thought to be the most massive single star, but the system's binary nature was confirmed in 2005.[69] Unfortunately, both component stars are largely obscured by circumstellar material ejected from Eta Carinae A and basic properties such as their temperatures and luminosities can only be inferred. Rapid changes to the stellar wind in the 21st century suggest that the star itself may be revealed as dust from the great eruption finally clears.[70]

Orbit

The binary nature of Eta Carinae is clearly established, although the components have not been directly observed and cannot even be clearly resolved spectroscopically due to scattering and re-excitation in the surrounding nebulosity. Periodic photometric and spectroscopic variations prompted the search for a companion, and modelling of the colliding winds and partial "eclipses" of some spectroscopic features have constrained the possible orbits.[14]

The period of the orbit is accurately known at 5.539 years, although this has changed over time due to mass loss and accretion. The period between the Great Eruption and the smaller 1890 eruption was 5.52 years, while before the Great Eruption it would have been lower still, probably between 4.8 and 5.4 years.[16] The orbital separation is only known approximately, with a semi-major axis of 15-16 astronomical units (AU). The orbit is highly eccentric, e = 0.9. This means that the separation of the stars varies from around 1.6 AU, similar to the distance of Mars from the sun, to 30 AU, similar to the distance of Neptune.[14]

Perhaps the most valuable use of an accurate orbit for a binary star system is to directly calculate the masses of the stars. This requires the dimensions and inclination of the orbit to be accurately known. Unfortunately the dimensions of Eta Carinae's orbit are only known approximately as the stars cannot be directly and separately observed. The inclination has been modelled at 130-145 degrees, but the orbit is still not known accurately enough to provide the masses of the two components.[14]

Classification

Eta Carinae A is classified as a luminous blue variable (LBV) due to the distinctive spectral and brightness variations. This type of variable star is characterised by irregular changes from a high temperature quiescent state to a low temperature outburst state at roughly constant luminosity. LBVs in the quiescent state lie on a narrow S Doradus instability strip, with more luminous stars being hotter. In outburst all LBVs have about the same temperature, which is near 8,000 K. LBVs in a normal outburst are visually brighter than when quiescent although the bolometric luminosity is unchanged.

A Great Eruption event similar to Eta Carinae A's has only been observed in one other star in our galaxy, P Cygni, and in a handful of other possible LBVs in external galaxies. None of them seem to be quite as violent as Eta Carinae's. It is unclear if this is something that only a very few of the most massive LBVs undergo, something that is caused by a close companion star, or a very brief but common phase for massive stars. Some similar events in external galaxies have been mistaken for supernovae and have been called supernova imposters, although this grouping may also include other types of non-terminal transients that approach the brightness of a supernova.[71]

Eta Carinae A is not a typical LBV. It is more luminous than any other LBV in the Milky Way although possibly comparable to other supernova imposters detected in external galaxies. It does not currently lie on the S Doradus instability strip, although it is unclear what the temperature or spectral type of the underlying star actually is. The 1890 eruption may have been fairly typical of LBV eruptions, with an early F spectral type, and it has been estimated that the star may currently have an opaque stellar wind forming a pseudo-photosphere with a temperature of 9,000 K - 14,000 K which would be typical for an LBV in eruption.[26]

Eta Carinae B is a massive luminous hot star, about which little else is known. From certain high excitation spectral lines that ought not to be produced by the primary, Eta Carinae B is thought to be a young O-type star. Most authors suggest it is a somewhat evolved star such as a supergiant or giant, although a Wolf-Rayet star cannot be ruled out.[69]

Mass

The masses of stars are difficult to measure except by determination of a binary orbit. Eta Carinae is a binary system, but certain key information about the orbit is not known accurately. Several models of the system use masses of 120-160 M☉ and 30-60 M☉ for the primary and secondary respectively. Eta Carinae A has clearly lost a great deal of mass since it formed and was initially 150-180 M☉.[10] Still higher masses have been suggested, to model the energy output and mass transfer of the Great Eruption, with a combined system mass of over 250 M☉ before the Great Eruption.[16]

Mass loss

Mass loss is one of the most intensively studied aspects of massive star research. Put simply, using observed mass loss rates in the best models of stellar evolution do not reproduce the observed distribution of evolved massive stars such as Wolf-Rayets, the number and types of core collapse supernovae, or their progenitors. To match those observations, the models require much higher mass loss rates. Eta Carinae A has one of the highest known mass loss rates, currently around 10-3 M☉/year, and is an obvious candidate for study.[10]

Eta Carinae A is losing so much mass due to its extreme luminosity and relatively low surface gravity that the stellar wind is entirely opaque and appears as a pseudo-photosphere. This optically dense surface hides the true physical surface of the star. During the Great Eruption the mass loss rate was a thousand times higher, around 1 M☉/year sustained for ten years or more. The total mass loss during the eruption was 10-20 M☉ with much of it now forming the Homunculus Nebula. The smaller 1890 eruption produced the Little Homunculus Nebula, much smaller and only about 0.1 M☉.[11] The bulk of the mass loss occurs in a wind with a terminal velocity of about 420 km/s, but some material is seen at higher velocities, up to 3,200 km/s, possibly material blown from the accretion disk by the secondary star.[72]

Eta Carinae B is presumably also losing mass via a thin fast stellar wind, but this cannot be detected directly. Models of the radiation observed from interactions between the winds of the two stars show a mass loss rate of the order of 10-5 M☉/year at speeds of 3,000 km/s, typical of a hot O class star.[52] For a portion of the highly eccentric orbit, it actually gains material from the primary via an accretion disk. During the Great Eruption of the primary, the secondary accreted several M☉, producing strong jets which formed the bipolar shape of the Homunculus Nebula.[10]

Luminosity

The stars of the Eta Carinae system are completely obscured by dust and opaque stellar winds. The total electromagnetic radiation across all wavelengths for both stars combined is several million L☉. The best estimate for the luminosity of the primary is 5 million L☉. The luminosity of Eta Carinae B is particularly uncertain, probably several hundred thousand L☉ and almost certainly no more than 1 million L☉. Due to the surrounding dust, 90% of the radiation from the stars reaches us as infra-red and Eta Carinae is the brightest IR source outside the solar system.[26]

The most notable feature of Eta Carinae is its giant eruption or supernova impostor event, which originated in the primary star and was observed around 1843. In a few years, it produced almost as much visible light as a faint supernova explosion, but the star survived. It is estimated that at peak brightness the luminosity was as high as 50 million L☉.[71] Other supernova impostors have been seen in other galaxies, for example the possible false supernova SN 1961v in NGC 1058[73] and SN 2006jc in UGC 4904.[74]

Following the Great Eruption, Eta Carinae became self-obscured by the ejected material, resulting in dramatic reddening. This has been estimated at four magnitudes at visual wavelengths, meaning the post-eruption luminosity was comparable to the luminosity when first identified.[75] Eta Carinae is still much brighter at infra-red wavelengths, despite the presumed hot stars behind the nebulosity. The recent visual brightening is considered to be largely due to a decrease in the extinction, due to thinning dust or a reduction in mass loss, rather than an underlying change in the luminosity.[70]

Temperature

The temperature of Eta Carinae B can be estimated with some accuracy due to spectral lines that are only likely to be produced by a star around 37,000 K.[5]

The temperature of the primary star is more uncertain. For many years it was expected to be over 30,000 K due to the presence of the high temperature spectral lines now attributed to the secondary star, although this conflicted with other spectral characteristics that ought only to be found in cooler stars. That conflict is now resolved, and Eta Carinae A, or at least what we can see of it, is accepted to be considerably cooler than Eta Carinae B. The star is likely to have been an early B hypergiant with a temperature of between 20,000 K and 25,000 K at the time of its dscovery by Halley. An effective temperature determined from the visible surface of the optically thick wind (at several hundred R☉) would be 9,400 K, while the temperature of a 60 R☉ hydrostatic "core" would be 35,200 K.[12][30][41][70]

The powerful stellar winds from the two stars collide and produce temperatures as high as 60 MK, which is the source of the hard x-rays and gamma-rays close to the stars. Further out, expanding gases from the Great Eruption collide with interstellar material and are heated to around 5 MK, producing less energetic x-rays seen in a horseshoe or ring shape.[76][77]

Size

The size of the two main stars in the Eta Carinae system is difficult to determine precisely because neither star can be seen directly. Eta Carinae B is likely to have a well-defined photosphere and its radius can be estimated from the assumed type of star. An O supergiant of 933,000 L☉ with a temperature of 37,200K has an effective radius of 23.6 R☉.[4]

The size of Eta Carinae A is not even well defined. It has an optically dense stellar wind so the typical definition of a star's surface being approximately where it becomes opaque gives a very different result to where a more traditional definition of a surface might be. One study calculated a radius of 60 R☉ for a hot "core" of 35,000K at optical depth 150, near the sonic point or very approximately what might be called a physical surface. At optical depth 0.67 the radius would be over 800 R☉, indicating an extended optically thick stellar wind.[39] At the peak of the Great Eruption the radius, so far as such a thing is meaningful during such a violent expulsion of material, would have been around 1,400 R☉, comparable to the largest known stars.[78]

The stellar sizes should be compared with their orbital separation, which is only around 250 R☉ at periastron. The accretion radius of the secondary is around 60 R☉, suggesting strong accretion near periastron leading to a collapse of the secondary wind.[16] It has been proposed that the initial brightening from 4th magnitude to 1st at relatively constant bolometric luminosity was a normal LBV outburst, albeit from an extreme example of the class. Then the companion star passing through the expanded photosphere of the primary at periastron triggered the further brightening, increase in luminosity, and extreme mass loss of the Great Eruption.[78]

Rotation

Rotation rates of massive stars have a critical influence on their evolution and eventual death. The rotation rate of the Eta Carinae stars cannot be measured directly because their surfaces cannot be seen. Single massive stars spin down quickly due to braking from their string winds, but there are hints that both Eta Carinae A and B are fast rotators, up to 90% of critical velocity. One or both could have been spun up by binary interaction, for example accretion onto the secondary, and orbital dragging on the primary.[79]

Future prospects

Eta Carinae is a unique object, with no very close analogues currently known in any galaxy. Therefore its future evolution is highly uncertain, but almost certainly involves further mass loss and an eventual supernova.[80]

Evolution

.png)

Eta Carinae A would have begun life as an extremely hot star on the main sequence, already a highly luminous object over a million L☉. The exact properties would depend on the initial mass, which is expected to have been at least 150 M☉ and possibly much higher. A typical spectrum when first formed would be O2If and the star would be fully convective due to CNO cycle fusion at the very high core temperatures.[81] As core hydrogen burning progressed, the star would slowly expand and become more luminous, becoming a blue hypergiant and eventually an LBV while still fusing hydrogen in the core. When hydrogen at the core is depleted, hydrogen shell burning continues with further increases in size and luminosity. While still in the LBV phase, core helium burning begins and the star starts to increase in temperature as it continues to lose mass. It is unclear whether helium fusion has started at the core of Eta Carinae A.[82]

Models of the evolution and death of single very massive stars predict an increase in temperature during helium core burning, with the outer layers of the star being lost. It becomes a Wolf Rayet star on the nitrogen sequence, moving from WNL to WNE as more of the outer layers are lost, possibly reaching the WC or WO spectral class as the carbon-oxygen core is exposed. This process would continue with heavier elements being fused until an iron core develops, at which point the core collapses and the star is destroyed. Subtle differences in initial conditions, in the models themselves, and most especially in the rates of mass loss, produce different predictions for the final state of the most massive stars. They may survive to become a bare carbon-oxygen core with a WO spectrum or they may collapse at an earlier stage while the star retains more of its outer layers.[83][84][85] The lack of sufficiently luminous WN stars and the discovery of apparent LBV supernova progenitors has also prompted the suggestion that certain types of LBVs explode as a supernova without evolving further.[86]

Eta Carinae is a close binary and this complicates the evolution of both stars. Compact massive companions can strip mass from larger primary stars much more quickly than would occur in a single star, so the properties at core collapse can be very different. In some scenarios, the secondary can accrue significant mass, accelerating its evolution, and in turn being stripped by the now compact Wolf Rayet primary.[87] In the case of Eta Carinae, the secondary is clearly causing additional instability in the primary, making it difficult to predict future developments.

Supernova

The overwhelming probability is that the next supernova observed in our galaxy will originate from an unknown white dwarf or anonymous red supergiant, very likely not even visible to the naked eye.[88] Nevertheless, the prospect of a supernova originating from an object as extreme, nearby, and well-studied as Eta Carinae arouses great interest.[89]

As a single star, an initial ≈150 M☉ star would typically reach core collapse as a Wolf Rayet star within 3 million years.[83] At low metallicity, many massive stars will collapse directly to a black hole with no visible explosion or a sub-luminous supernova, and a small fraction will produce a pair instability supernova, but at solar metallicity and above there is expected to be sufficient mass loss before collapse to allow a visible supernova of type Ib or Ic.[90] If there is still a large amount of expelled material close to the star, the shock formed by the supernova explosion impacting the circumstellar material can efficiently convert kinetic energy to radiation, resulting in a superluminous supernova (commonly called a hypernova), several times more luminous than a typical core collapse supernova and much longer-lasting. Highly massive progenitors may also eject sufficient nickel to cause a hypernova simply from the radioactive decay.[91] The resulting remnant would be a black hole since it is highly unlikely such a massive star could ever lose sufficient mass for the core not to exceed the limit for a neutron star.[92] Certain supernovae may also produce gamma-ray bursts, but this is not expected from a single star in the mass range of Eta Carinae.[83]

The existence of a massive companion brings many other possibilities. If Eta Carinae A was rapidly stripped of its outer layers, it might be a less massive WC or WO star when core collapse was reached. This would result in a type Ib or type Ic supernova due to the lack of hydrogen and possibly helium. This supernova type is thought to be the originator of certain classes of gamma ray bursts, but models predict they occur only in less massive stars.[87][93]

Several unusual supernovae and imposters have been compared to Eta Carinae as examples of its possible fate. One of the most compelling is SN 2009ip, a blue supergiant which underwent a supernova imposter event in 2009 with similarities to Eta Carinae's Great Eruption, then an even brighter outburst in 2012 which is likely to have been a true supernova.[94] SN 2006jc, some 77 million light years away in UGC 4904, in the constellation Lynx, also underwent a supernova imposter brightening, in 2004, followed by a magnitude 13.8 type Ib supernova, first seen on 9 October 2006. Eta Carinae has also been compared to other possible supernova imposters sycj as SN 1961V, and to superluminous supernovae such as SN 2006gy.

Possible effects on Earth

A typical core collapse supernova at the distance of Eta Carinae would peak at an apparent magnitude around -4, similar to Venus. A hypernova could be five magnitudes brighter, potentially the brightest supernova in recorded history (currently SN 1006). At 7,500 light years from the star it is unlikely to directly affect terrestrial lifeforms, as they will be protected from gamma rays by the atmosphere and from some other cosmic rays by the magnetosphere. The main damage would be restricted to the upper atmosphere, the ozone layer, spacecraft, including satellites, and any astronauts in space. However, at least one paper has projected that complete loss of the Earth's ozone layer is a plausible consequence of a nearby supernova, which would result in a significant increase in surface UV radiation reaching the Earth's surface from our own Sun.[95] Another discusses more subtle effects from the unusual illumination.[96]

Eta Carinae is not expected to produce a gamma ray burst and its axis is not currently aimed near Earth, but a direct hit from a GRB could cause catastrophic damage and a major extinction event. Calculations show that the deposited energy of such a GRB striking the Earth's atmosphere would be equivalent to one kiloton of TNT per square kilometer over the entire hemisphere facing the star, with ionizing radiation depositing ten times the lethal whole body dose to the surface.[97]

Cultural significance

In traditional Chinese astronomy, Eta Carinae has the names Tseen She (from the Chinese 天社 [Mandarin: tiānshè] "Heaven's altar") and Foramen. It is also known as 海山二 (Hǎi Shān èr, English: the Second Star of Sea and Mountain),[98] referring to Sea and Mountain, an asterism that Eta Carinae forms with s Carinae, λ Centauri and λ Muscae.[99]

See also

- Bipolar outflow

- List of largest stars

- List of most luminous stars

- List of most massive stars

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Høg, E.; Fabricius, C.; Makarov, V. V.; Urban, S.; Corbin, T.; Wycoff, G.; Bastian, U.; Schwekendiek, P.; Wicenec, A. (2000). "The Tycho-2 catalogue of the 2.5 million brightest stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics 355: L27. Bibcode:2000A&A...355L..27H.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Samus, N. N.; Durlevich, O. V. et al. (2009). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: General Catalogue of Variable Stars (Samus+ 2007-2013)". VizieR On-line Data Catalog: B/gcvs. Originally published in: 2009yCat....102025S 1: 02025. Bibcode:2009yCat....102025S.

- ↑ Skiff, B. A. (2014). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: Catalogue of Stellar Spectral Classifications (Skiff, 2009-2014)". VizieR On-line Data Catalog: B/mk. Originally published in: Lowell Observatory (October 2014) 1: 2023. Bibcode:2014yCat....1.2023S.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Verner, E.; Bruhweiler, F.; Gull, T. (2005). "The Binarity of η Carinae Revealed from Photoionization Modeling of the Spectral Variability of the Weigelt Blobs B and D". The Astrophysical Journal 624 (2): 973. Bibcode:2005ApJ...624..973V. doi:10.1086/429400.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Mehner, Andrea; Davidson, Kris; Ferland, Gary J.; Humphreys, Roberta M. (2010). "High-excitation Emission Lines near Eta Carinae, and Its Likely Companion Star". The Astrophysical Journal 710: 729. Bibcode:2010ApJ...710..729M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/710/1/729.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Ducati, J. R. (2002). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: Catalogue of Stellar Photometry in Johnson's 11-color system". CDS/ADC Collection of Electronic Catalogues 2237: 0. Bibcode:2002yCat.2237....0D.

- ↑ Wilson, Ralph Elmer (1953). "General catalogue of stellar radial velocities". Washington: 0. Bibcode:1953GCRV..C......0W.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Walborn, Nolan R. (2012). "The Company Eta Carinae Keeps: Stellar and Interstellar Content of the Carina Nebula". Eta Carinae and the Supernova Impostors. Astrophysics and Space Science Library 384. pp. 25–27. Bibcode:2012ASSL..384...25W. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-2275-4_2. ISBN 978-1-4614-2274-7.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Smith, Nathan; Frew, David J. (2011). "A revised historical light curve of Eta Carinae and the timing of close periastron encounters". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 415 (3): 2009–19. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.415.2009S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18993.x.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Kashi, A.; Soker, N. (2009). "Possible implications of mass accretion in Eta Carinae". New Astronomy 14: 11. arXiv:0802.0167. Bibcode:2009NewA...14...11K. doi:10.1016/j.newast.2008.04.003.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Gull, T. R.; Damineli, A. (2010). "JD13 – Eta Carinae in the Context of the Most Massive Stars". Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union 5: 373. arXiv:0910.3158. Bibcode:2010HiA....15..373G. doi:10.1017/S1743921310009890.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Groh, Jose H.; Hillier, D. John; Madura, Thomas I.; Weigelt, Gerd (2012). "On the influence of the companion star in Eta Carinae: 2D radiative transfer modelling of the ultraviolet and optical spectra". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 423 (2): 1623. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.423.1623G. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.20984.x.

- ↑ Damineli, A.; Hillier, D. J.; Corcoran, M. F.; Stahl, O.; Levenhagen, R. S.; Leister, N. V.; Groh, J. H.; Teodoro, M.; Albacete Colombo, J. F.; Gonzalez, F.; Arias, J.; Levato, H.; Grosso, M.; Morrell, N.; Gamen, R.; Wallerstein, G.; Niemela, V. (2008). "The periodicity of the η Carinae events†‡§¶". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 384 (4): 1649. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.384.1649D. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.12815.x.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Madura, T. I.; Gull, T. R.; Owocki, S. P.; Groh, J. H.; Okazaki, A. T.; Russell, C. M. P. (2012). "Constraining the absolute orientation of η Carinae's binary orbit: A 3D dynamical model for the broad [Fe III] emission". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 420 (3): 2064. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.420.2064M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.20165.x.

- ↑ Damineli, Augusto; Conti, Peter S.; Lopes, Dalton F. (1997). "Eta Carinae: A long period binary?". New Astronomy 2 (2): 107. Bibcode:1997NewA....2..107D. doi:10.1016/S1384-1076(97)00008-0.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Kashi, Amit; Soker, Noam (2010). "Periastron Passage Triggering of the 19th Century Eruptions of Eta Carinae". The Astrophysical Journal 723: 602. Bibcode:2010ApJ...723..602K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/723/1/602.

- ↑ Will Gater; Anton Vamplew; Jacqueline Mitton. The practical astronomer. ISBN 9781405356206.

- ↑ Allen, Richard Hinckley (1963). Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning. Dover Publications. p. 73. ISBN 978-0486210797.

- ↑ Gould, Benjamin Apthorp (1879). "Uranometria Argentina : Brillantez Y posicion de las estrellas fijas, hasta la septima magnitud, comprendidas dentro de cien grados del polo austral : Con atlas". Resultados del Observatorio Nacional Argentino en Cordoba ; v. 1 1. Bibcode:1879RNAO....1.....G.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Johansson, S.; Letokhov, V. S. (2005). "Astrophysical laser operating in the OI 8446-Åline in the Weigelt blobs of η Carinae". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 364 (2): 731. Bibcode:2005MNRAS.364..731J. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2005.09605.x.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Frew, David J. (2004). "The Historical Record of η Carinae I. The Visual Light Curve, 1595-2000". The Journal of Astronomical Data 10: 6. Bibcode:2004JAD....10....6F.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Burbidge, G. R. (1962). "A Speculation Concerning the Evolutionary State of Eta Carinae". Astrophysical Journal 136: 304. Bibcode:1962ApJ...136..304B. doi:10.1086/147376.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Herschel, John Frederick William (1847). Results of astronomical observations made during the years 1834, 5, 6, 7, 8, at the Cape of Good Hope: being the completion of a telescopic survey of the whole surface of the visible heavens, commenced in 1825 1. London, United Kingdom: Smith, Elder and Co. pp. 33–35.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Damineli, A. (1996). "The 5.52 Year Cycle of Eta Carinae". Astrophysical Journal Letters v.460 460: L49. Bibcode:1996ApJ...460L..49D. doi:10.1086/309961.

- ↑ Hamacher, D. W.; Frew, D. J. (2010). "An Aboriginal Australian Record of the Great Eruption of Eta Carinae". Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage 13 (3): 220–34. arXiv:1010.4610. Bibcode:2010JAHH...13..220H.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Davidson, Kris; Humphreys, Roberta M. (1997). "Eta Carinae and Its Environment". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 35: 1. Bibcode:1997ARA&A..35....1D. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.35.1.1.

- ↑ Smith, Nathan (2004). "The systemic velocity of Eta Carinae". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 351: L15. Bibcode:2004MNRAS.351L..15S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.07943.x.

- ↑ Ishibashi, Kazunori; Gull, Theodore R.; Davidson, Kris; Smith, Nathan; Lanz, Thierry; Lindler, Don; Feggans, Keith; Verner, Ekaterina; Woodgate, Bruce E.; Kimble, Randy A.; Bowers, Charles W.; Kraemer, Steven; Heap, Sarah R.; Danks, Anthony C.; Maran, Stephen P.; Joseph, Charles L.; Kaiser, Mary Elizabeth; Linsky, Jeffrey L.; Roesler, Fred; Weistrop, Donna (2003). "Discovery of a Little Homunculus within the Homunculus Nebula of η Carinae". The Astronomical Journal 125 (6): 3222. Bibcode:2003AJ....125.3222I. doi:10.1086/375306.

- ↑ Thackeray, A. D. (1953). "Stars, Variable: Note on the brightening of Eta Carinae". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 113: 237. Bibcode:1953MNRAS.113..237T.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Martin, John C.; Davidson, Kris; Humphreys, Roberta M.; Mehner, Andrea (2010). "Mid-cycle Changes in Eta Carinae". The Astronomical Journal 139 (5): 2056. Bibcode:2010AJ....139.2056M. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/139/5/2056.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Landes, H.; Fitzgerald, M. (2010). "Photometric Observations of the η Carinae 2009.0 Spectroscopic Event". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia 27 (3): 374. Bibcode:2010PASA...27..374L. doi:10.1071/AS09036.

- ↑ Walborn, N. R.; Liller, M. H. (1977). "The earliest spectroscopic observations of eta Carinae and its interaction with the Carina Nebula". Astrophysical Journal 211: 181. Bibcode:1977ApJ...211..181W. doi:10.1086/154917.

- ↑ Baxandall, F. E. (1919). "Note on apparent changes in the spectrum of η Carinæ". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 79: 619. Bibcode:1919MNRAS..79..619B.

- ↑ Gaviola, E. (1953). "Eta Carinae. II. The Spectrum". Astrophysical Journal 118: 234. Bibcode:1953ApJ...118..234G. doi:10.1086/145746.

- ↑ Rest, A.; Prieto, J. L.; Walborn, N. R.; Smith, N.; Bianco, F. B.; Chornock, R.; Welch, D. L.; Howell, D. A.; Huber, M. E.; Foley, R. J.; Fong, W.; Sinnott, B.; Bond, H. E.; Smith, R. C.; Toledo, I.; Minniti, D.; Mandel, K. (2012). "Light echoes reveal an unexpectedly cool η Carinae during its nineteenth-century Great Eruption". Nature 482 (7385): 375. Bibcode:2012Natur.482..375R. doi:10.1038/nature10775. PMID 22337057.

- ↑ Prieto, J. L.; Rest, A.; Bianco, F. B.; Matheson, T.; Smith, N.; Walborn, N. R.; Hsiao, E. Y.; Chornock, R.; Paredes Álvarez, L.; Campillay, A.; Contreras, C.; González, C.; James, D.; Knapp, G. R.; Kunder, A.; Margheim, S.; Morrell, N.; Phillips, M. M.; Smith, R. C.; Welch, D. L.; Zenteno, A. (2014). "Light Echoes from η Carinae's Great Eruption: Spectrophotometric Evolution and the Rapid Formation of Nitrogen-rich Molecules". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 787: L8. Bibcode:2014ApJ...787L...8P. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/787/1/L8.

- ↑ Davidson, K.; Dufour, R. J.; Walborn, N. R.; Gull, T. R. (1986). "Ultraviolet and visual wavelength spectroscopy of gas around ETA Carinae". Astrophysical Journal 305: 867. Bibcode:1986ApJ...305..867D. doi:10.1086/164301.

- ↑ Davidson, Kris; Ebbets, Dennis; Weigelt, Gerd; Humphreys, Roberta M.; Hajian, Arsen R.; Walborn, Nolan R.; Rosa, Michael (1995). "HST/FOS spectroscopy of ETA Carinae: The star itself, and ejecta within 0.3 arcsec". Astronomical Journal (ISSN 0004-6256) 109: 1784. Bibcode:1995AJ....109.1784D. doi:10.1086/117408.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 D. John Hillier; K. Davidson; K. Ishibashi; T. Gull (June 2001). "On the Nature of the Central Source in η Carinae". ApJ 553 (837): 837. Bibcode:2001ApJ...553..837H. doi:10.1086/320948.

- ↑ Hillier, D. J.; Allen, D. A. (1992). "A spectroscopic investigation of Eta Carinae and the Homunculus Nebula. I - Overview of the spectra". Astronomy and Astrophysics (ISSN 0004-6361) 262: 153. Bibcode:1992A&A...262..153H.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Martin, John C.; Mehner, A.; Ishibashi, K.; Davidson, K.; Humphreys, R. M. (2014). "Eta Carinae's change of state: First new HST/NUV data since 2010, and the first new FUV since 2004". American Astronomical Society 223. Bibcode:2014AAS...22315109M.

- ↑ Davidson, Kris; Mehner, Andrea; Humphreys, Roberta; Martin, John C.; Ishibashi, Kazunori (2014). "Eta Carinae's 2014.6 Spectroscopic Event: The Extraordinary He II and N II Features" 1411. p. 695. arXiv:1411.0695. Bibcode:2014arXiv1411.0695D.

- ↑ Hill, R. W.; Burginyon, G.; Grader, R. J.; Palmieri, T. M.; Seward, F. D.; Stoering, J. P. (1972). "A Soft X-Ray Survey from the Galactic Center to VELA". Astrophysical Journal 171: 519. Bibcode:1972ApJ...171..519H. doi:10.1086/151305.

- ↑ Seward, F. D.; Page, C. G.; Turner, M. J. L.; Pounds, K. A. (1976). "X-ray sources in the southern Milky Way". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 177: 13P. Bibcode:1976MNRAS.177P..13S.

- ↑ Becker, R. H.; Boldt, E. A.; Holt, S. S.; Pravdo, S. H.; Rothschild, R. E.; Serlemitsos, P. J.; Swank, J. H. (1976). "X-ray emission from the supernova remnant G287.8-0.5". Astrophysical Journal 209: L65. Bibcode:1976ApJ...209L..65B. doi:10.1086/182269.

- ↑ Forman, W.; Jones, C.; Cominsky, L.; Julien, P.; Murray, S.; Peters, G.; Tananbaum, H.; Giacconi, R. (1978). "The fourth Uhuru catalog of X-ray sources". Astrophysical Journal 38: 357. Bibcode:1978ApJS...38..357F. doi:10.1086/190561.

- ↑ Seward, F. D.; Forman, W. R.; Giacconi, R.; Griffiths, R. E.; Harnden, F. R.; Jones, C.; Pye, J. P. (1979). "X-rays from Eta Carinae and the surrounding nebula". Astrophysical Journal 234: L55. Bibcode:1979ApJ...234L..55S. doi:10.1086/183108.

- ↑ Corcoran, M. F.; Rawley, G. L.; Swank, J. H.; Petre, R. (1995). "First detection of x-ray variability of eta carinae". Astrophysical Journal 445: L121. Bibcode:1995ApJ...445L.121C. doi:10.1086/187904.

- ↑ Tsuboi, Yohko; Koyama, Katsuji; Sakano, Masaaki; Petre, Robert (1997). "ASCA Observations of Eta Carinae". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan 49: 85. Bibcode:1997PASJ...49...85T. doi:10.1093/pasj/49.1.85.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Tavani, M.; Sabatini, S.; Pian, E.; Bulgarelli, A.; Caraveo, P.; Viotti, R. F.; Corcoran, M. F.; Giuliani, A.; Pittori, C.; Verrecchia, F.; Vercellone, S.; Mereghetti, S.; Argan, A.; Barbiellini, G.; Boffelli, F.; Cattaneo, P. W.; Chen, A. W.; Cocco, V.; d'Ammando, F.; Costa, E.; Deparis, G.; Del Monte, E.; Di Cocco, G.; Donnarumma, I.; Evangelista, Y.; Ferrari, A.; Feroci, M.; Fiorini, M.; Froysland, T. et al. (2009). "Detection of Gamma-Ray Emission from the Eta-Carinae Region". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 698 (2): L142. Bibcode:2009ApJ...698L.142T. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/698/2/L142.

- ↑ Leyder, J.-C.; Walter, R.; Rauw, G. (2008). "Hard X-ray emission from η Carinae". Astronomy and Astrophysics 477 (3): L29. Bibcode:2008A&A...477L..29L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078981.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Pittard, J. M.; Corcoran, M. F. (2002). "In hot pursuit of the hidden companion of eta Carinae: An X-ray determination of the wind parameters". Astronomy and Astrophysics 383 (2): 636. Bibcode:2002A&A...383..636P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20020025.

- ↑ Weis, K.; Duschl, W. J.; Bomans, D. J. (2001). "High velocity structures in, and the X-ray emission from the LBV nebula around η Carinae". Astronomy and Astrophysics 367 (2): 566. Bibcode:2001A&A...367..566W. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20000460.

- ↑ Hamaguchi, K.; Corcoran, M. F.; Gull, T.; Ishibashi, K.; Pittard, J. M.; Hillier, D. J.; Damineli, A.; Davidson, K.; Nielsen, K. E.; Kober, G. V. (2007). "X‐Ray Spectral Variation of η Carinae through the 2003 X‐Ray Minimum". The Astrophysical Journal 663: 522. arXiv:astro-ph/0702409. Bibcode:2007ApJ...663..522H. doi:10.1086/518101.

- ↑ Abdo, A. A.; Ackermann, M.; Ajello, M.; Allafort, A.; Baldini, L.; Ballet, J.; Barbiellini, G.; Bastieri, D.; Bechtol, K.; Bellazzini, R.; Berenji, B.; Blandford, R. D.; Bonamente, E.; Borgland, A. W.; Bouvier, A.; Brandt, T. J.; Bregeon, J.; Brez, A.; Brigida, M.; Bruel, P.; Buehler, R.; Burnett, T. H.; Caliandro, G. A.; Cameron, R. A.; Caraveo, P. A.; Carrigan, S.; Casandjian, J. M.; Cecchi, C.; Çelik, Ö. et al. (2010). "Fermi Large Area Telescope Observation of a Gamma-ray Source at the Position of Eta Carinae". The Astrophysical Journal 723: 649. Bibcode:2010ApJ...723..649A. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/723/1/649.

- ↑ Abraham, Z.; Falceta-Gonçalves, D.; Dominici, T. P.; Nyman, L.-Å.; Durouchoux, P.; McAuliffe, F.; Caproni, A.; Jatenco-Pereira, V. (2005). "Millimeter-wave emission during the 2003 low excitation phase of η Carinae". Astronomy and Astrophysics 437 (3): 977. Bibcode:2005A&A...437..977A. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20041604.

- ↑ Kashi, Amit; Soker, Noam (2007). "Modelling the Radio Light Curve of Eta Carinae". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 378 (4): 1609–1618. arXiv:astro-ph/0702389. Bibcode:2007astro.ph..2389K. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.11908.x.

- ↑ Bortle, John E. (2001). "Introducing the Bortle Dark-Sky Scale". Sky and Telescope 101: 126. Bibcode:2001S&T...101b.126B.

- ↑ Thompson, Mark (2013). A Down to Earth Guide to the Cosmos. Random House. ISBN 9781448126910.

- ↑ Ian Ridpath. Astronomy. ISBN 9781405336208.

- ↑ Wolk, Scott J.; Broos, Patrick S.; Getman, Konstantin V.; Feigelson, Eric D.; Preibisch, Thomas; Townsley, Leisa K.; Wang, Junfeng; Stassun, Keivan G.; King, Robert R.; McCaughrean, Mark J.; Moffat, Anthony F. J.; Zinnecker, Hans (2011). "The Chandra Carina Complex Project View of Trumpler 16". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement 194 (1): 15. Bibcode:2011ApJS..194...12W. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/194/1/12. 12.

- ↑ Turner, D. G.; Grieve, G. R.; Herbst, W.; Harris, W. E. (1980). "The young open cluster NGC 3293 and its relation to CAR OB1 and the Carina Nebula complex". Astronomical Journal 85: 1193. Bibcode:1980AJ.....85.1193T. doi:10.1086/112783.

- ↑ Aitken, D. K.; Jones, B. (1975). "The infrared spectrum and structure of Eta Carinae". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 172: 141. Bibcode:1975MNRAS.172..141A.

- ↑ Weigelt, G.; Ebersberger, J. (1986). "Eta Carinae resolved by speckle interferometry". Astronomy and Astrophysics (ISSN 0004-6361) 163: L5. Bibcode:1986A&A...163L...5W.

- ↑ Van Leeuwen, F. (2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics 474 (2): 653. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357.

- ↑ The, P. S.; Bakker, R.; Antalova, A. (1980). "Studies of the Carina Nebula. IV - A new determination of the distances of the open clusters TR 14, TR 15, TR 16 and CR 228 based on Walraven photometry". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series 41: 93. Bibcode:1980A&AS...41...93T.

- ↑ Walborn, N. R. (1995). "The Stellar Content of the Carina Nebula (Invited Paper)". Revista Mexicana de Astronomia y Astrofisica Serie de Conferencias 2: 51. Bibcode:1995RMxAC...2...51W.

- ↑ Hur, Hyeonoh; Sung, Hwankyung; Bessell, Michael S. (2012). "Distance and the Initial Mass Function of Young Open Clusters in the η Carina Nebula: Tr 14 and Tr 16". The Astronomical Journal 143 (2): 41. Bibcode:2012AJ....143...41H. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/143/2/41.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Iping, R. C.; Sonneborn, G.; Gull, T. R.; Ivarsson, S.; Nielsen, K. (2005). "Searching for Radial Velocity Variations in eta Carinae". American Astronomical Society Meeting 207 207: 1445. Bibcode:2005AAS...20717506I.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 Mehner, Andrea; Davidson, Kris; Humphreys, Roberta M.; Ishibashi, Kazunori; Martin, John C.; Ruiz, María Teresa; Walter, Frederick M. (2012). "Secular Changes in Eta Carinae's Wind 1998-2011". The Astrophysical Journal 751: 73. Bibcode:2012ApJ...751...73M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/751/1/73.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Davidson, Kris; Humphreys, Roberta M. (2012). Eta Carinae and the Supernova Impostors. Astrophysics and Space Science Library 384. New York, New York: Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 26–27. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-2275-4. ISBN 978-1-4614-2274-7.

- ↑ Soker, Noam (2004). "Why a Single-Star Model Cannot Explain the Bipolar Nebula of η Carinae". The Astrophysical Journal 612 (2): 1060. Bibcode:2004ApJ...612.1060S. doi:10.1086/422599.

- ↑ Stockdale, Christopher J.; Rupen, Michael P.; Cowan, John J.; Chu, You-Hua; Jones, Steven S. (2001). "The fading radio emission from SN 1961v: evidence for a Type II peculiar supernova?". The Astronomical Journal 122 (1): 283. arXiv:astro-ph/0104235. Bibcode:2001AJ....122..283S. doi:10.1086/321136.

- ↑ Pastorello, A.; Smartt, S. J.; Mattila, S.; Eldridge, J. J.; Young, D.; Itagaki, K.; Yamaoka, H.; Navasardyan, H.; Valenti, S.; Patat, F.; Agnoletto, I.; Augusteijn, T.; Benetti, S.; Cappellaro, E.; Boles, T.; Bonnet-Bidaud, J.-M.; Botticella, M. T.; Bufano, F.; Cao, C.; Deng, J.; Dennefeld, M.; Elias-Rosa, N.; Harutyunyan, A.; Keenan, F. P.; Iijima, T.; Lorenzi, V.; Mazzali, P. A.; Meng, X.; Nakano, S. et al. (2007). "A giant outburst two years before the core-collapse of a massive star". Nature 447 (7146): 829. Bibcode:10.1038/nature05825. doi:10.1038/nature05825. PMID 17568740.

- ↑ Smith, Nathan; Li, Weidong; Silverman, Jeffrey M.; Ganeshalingam, Mohan; Filippenko, Alexei V. (2011). "Luminous blue variable eruptions and related transients: Diversity of progenitors and outburst properties". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 415: 773. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.415..773S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18763.x.

- ↑ Corcoran, Michael F.; Ishibashi, Kazunori; Davidson, Kris; Swank, Jean H.; Petre, Robert; Schmitt, Jurgen H. M. M. (1997). "Increasing X-ray emissions and periodic outbursts from the massive star Eta Carinae". Nature 390 (6660): 587. Bibcode:1997Natur.390..587C. doi:10.1038/37558.

- ↑ Chlebowski, T.; Seward, F. D.; Swank, J.; Szymkowiak, A. (1984). "X-rays from Eta Carinae". Astrophysical Journal 281: 665. Bibcode:1984ApJ...281..665C. doi:10.1086/162143.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Smith, Nathan (2011). "Explosions triggered by violent binary-star collisions: Application to Eta Carinae and other eruptive transients". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 415 (3): 2020. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.415.2020S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18607.x.

- ↑ Groh, J. H.; Madura, T. I.; Owocki, S. P.; Hillier, D. J.; Weigelt, G. (2010). "Is Eta Carinae a Fast Rotator, and How Much Does the Companion Influence the Inner Wind Structure?". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 716 (2): L223. Bibcode:2010ApJ...716L.223G. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/716/2/L223.

- ↑ Khan, Rubab; Kochanek, C. S.; Stanek, K. Z.; Gerke, Jill (2015). "Finding η Car Analogs in Nearby Galaxies Using Spitzer. II. Identification of an Emerging Class of Extragalactic Self-Obscured Stars". The Astrophysical Journal 799 (2): 187. Bibcode:2015ApJ...799..187K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/799/2/187.

- ↑ Smith, Nathan (2006). "A census of the Carina Nebula - I. Cumulative energy input from massive stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 367 (2): 763. Bibcode:2006MNRAS.367..763S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10007.x.

- ↑ Groh, Jose H.; Meynet, Georges; Ekström, Sylvia; Georgy, Cyril (2014). "The evolution of massive stars and their spectra. I. A non-rotating 60 M⊙ star from the zero-age main sequence to the pre-supernova stage". Astronomy & Astrophysics 564: A30. Bibcode:2014A&A...564A..30G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201322573.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 83.2 Groh, Jose H.; Meynet, Georges; Georgy, Cyril; Ekström, Sylvia (2013). "Fundamental properties of core-collapse supernova and GRB progenitors: Predicting the look of massive stars before death". Astronomy & Astrophysics 558: A131. Bibcode:2013A&A...558A.131G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321906.

- ↑ Meynet, Georges; Georgy, Cyril; Hirschi, Raphael; Maeder, André; Massey, Phil; Przybilla, Norbert; Nieva, M.-Fernanda (2011). "Red Supergiants, Luminous Blue Variables and Wolf-Rayet stars: The single massive star perspective". Société Royale des Sciences de Liège 80: 266. Bibcode:2011BSRSL..80..266M.

- ↑ Ekström, S.; Georgy, C.; Eggenberger, P.; Meynet, G.; Mowlavi, N.; Wyttenbach, A.; Granada, A.; Decressin, T.; Hirschi, R.; Frischknecht, U.; Charbonnel, C.; Maeder, A. (2012). "Grids of stellar models with rotation. I. Models from 0.8 to 120 M⊙ at solar metallicity (Z = 0.014)". Astronomy & Astrophysics 537: A146. Bibcode:2012A&A...537A.146E. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201117751.

- ↑ Smith, Nathan; Conti, Peter S. (2008). "On the Role of the WNH Phase in the Evolution of Very Massive Stars: Enabling the LBV Instability with Feedback". The Astrophysical Journal 679 (2): 1467. Bibcode:2008ApJ...679.1467S. doi:10.1086/586885.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 Sana, H.; De Mink, S. E.; De Koter, A.; Langer, N.; Evans, C. J.; Gieles, M.; Gosset, E.; Izzard, R. G.; Le Bouquin, J.- B.; Schneider, F. R. N. (2012). "Binary Interaction Dominates the Evolution of Massive Stars". Science 337 (6093): 444. Bibcode:2012Sci...337..444S. doi:10.1126/science.1223344. PMID 22837522.

- ↑ Adams, Scott M.; Kochanek, C. S.; Beacom, John F.; Vagins, Mark R.; Stanek, K. Z. (2013). "Observing the Next Galactic Supernova". The Astrophysical Journal 778 (2): 164. Bibcode:2013ApJ...778..164A. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/778/2/164.

- ↑ McKinnon, Darren; Gull, T. R.; Madura, T. (2014). "Eta Carinae: An Astrophysical Laboratory to Study Conditions During the Transition Between a Pseudo-Supernova and a Supernova". American Astronomical Society 223. Bibcode:2014AAS...22340503M.

- ↑ Heger, A.; Fryer, C. L.; Woosley, S. E.; Langer, N.; Hartmann, D. H. (2003). "How Massive Single Stars End Their Life". The Astrophysical Journal 591: 288. Bibcode:2003ApJ...591..288H. doi:10.1086/375341.

- ↑ Gal-Yam, A. (2012). "Luminous Supernovae". Science 337 (6097): 927–32. Bibcode:10.1126/science.1203601. doi:10.1126/science.1203601. PMID 22923572.

- ↑ Smith, Nathan; Owocki, Stanley P. (2006). "On the Role of Continuum-driven Eruptions in the Evolution of Very Massive Stars". The Astrophysical Journal 645 (1): L45. arXiv:astro-ph/0606174. Bibcode:2006ApJ...645L..45S. doi:10.1086/506523.

- ↑ Claeys, J. S. W.; De Mink, S. E.; Pols, O. R.; Eldridge, J. J.; Baes, M. (2011). "Binary progenitor models of type IIb supernovae". Astronomy & Astrophysics 528: A131. Bibcode:2011A&A...528A.131C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201015410.

- ↑ Smith, Nathan; Mauerhan, Jon C.; Prieto, Jose L. (2014). "SN 2009ip and SN 2010mc: Core-collapse Type IIn supernovae arising from blue supergiants". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 438 (2): 1191. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.438.1191S. doi:10.1093/mnras/stt2269.

- ↑ Ruderman, M. A. (1974). "Possible Consequences of Nearby Supernova Explosions for Atmospheric Ozone and Terrestrial Life". Science 184 (4141): 1079–81. Bibcode:1974Sci...184.1079R. doi:10.1126/science.184.4141.1079. PMID 17736193.

- ↑ Thomas, Brian; Melott, A. L.; Fields, B. D.; Anthony-Twarog, B. J. (2008). "Superluminous Supernovae: No Threat from Eta Carinae". American Astronomical Society 212: 193. Bibcode:2008AAS...212.0405T.

- ↑ Arnon Dar; A. De Rujula (2002). The threat to life from Eta Carinae and gamma ray bursts. Astrophysics and Gamma Ray Physics in Space 24. pp. 513–523. arXiv:astro-ph/0110162. Bibcode:2001astro.ph.10162D.

- ↑ 陳輝樺, ed. (28 July 2006). "AEEA 天文教育資訊網" (in Chinese). Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ↑ 陳久金 (2005). 中國星座神 (in Chinese). 台灣書房出版有限公司. ISBN 978-986-7332-25-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eta Carinae. |

- Reddy, Francis (6 January 2015). "NASA Observatories Take an Unprecedented Look into Superstar Eta Carinae (video)". NASA website. Greenbelt, Maryland: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center,. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- Lajús, Eduardo Fernández (1 October 2014). "Optical monitoring of Eta Carinae". Facultad de Ciencias Astronómicas y Geofísicas, Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- Eta Carinae profile at Solstation

- X-ray Monitoring by RXTE

- The 2003 Observing Campaign

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||