Escutcheon (heraldry)

In heraldry, an escutcheon /ɨˈskʌtʃən/ is a shield which forms the main or focal element in an achievement of arms. The word is used in two related senses.

Firstly, as the shield on which a coat of arms is displayed. Escutcheon shapes are derived from actual shields used by knights in combat, and thus have varied and developed by region and by era. As this shape has been regarded as a war-like device appropriate to men only, British ladies customarily bear their arms upon a lozenge, or diamond-shape, while clergymen and ladies in continental Europe bear theirs on a cartouche, or oval. Other shapes are in use, such as the roundel commonly used for arms granted to Aboriginal Canadians by the Canadian Heraldic Authority.

Secondly, a shield can itself be a charge within a coat of arms. More often, a smaller shield is placed over the middle of the main shield (in pretence or en surtout) as a form of marshalling. In either case, the smaller shield is usually given the same shape as the main shield. When there is only one such shield, it is sometimes called an inescutcheon.

Etymology

The word escutcheon is derived from Middle English escochon, from Anglo-Norman escuchon, from Vulgar Latin scūtiōn-, from Latin scūtum, "shield".[2] From its use in heraldry, escutcheon can be a metaphor for a family's honour. The idiom "a blot on the escutcheon" is used to mean a stain on somebody's reputation.[3]

Varying shapes

The almost full body-length shield used by the Normans at the Battle of Hastings and seen depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry (c. 1066), occasionally with proto-heraldic cognizances painted thereon, pre-dates the era of heraldry proper, which commenced during the first quarter of the 13th century. By about 1250 the shields used in warfare were almost triangular in shape, referred to as heater shields. Such a shape can be seen on the effigy of William II Longespée (d.1250) at Salisbury Cathedral, whilst the shield shown on the effigy of his father William Longespée, 3rd Earl of Salisbury (d.1226) is of a more elongated form. That on the enamel monument to the latter's grandfather Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou (d.1151) is of almost full-body length. This heater-shaped form was used in warfare during the apogee of the Age of Chivalry, at about the time of the Battle of Crecy (1346) and the founding of the Order of the Garter (1348), when the art of Heraldry reached its greatest perfection. This almost equilateral shape is therefore used as a setting for armorials from this "classical age" of heraldry, in the sense that it produced the best examples of the art.

In the Tudor era the heraldic escutcheon took the shape of an inverted Tudor arch. Continental European designs frequently use the various forms used in jousting, which incorporate "mouths" used as lance rests into the shields; such escutcheons are known as à bouche. The mouth is correctly shown on the dexter side only, as jousting pitches were designed for right-handed knights. Heraldic examples of English shields à bouche can be seen in the spandrels of the trussed timber roof of Lincoln's Inn Hall, London.

Points

The points of the shield refer to specific positions thereon and are used in blazons to describe where a charge should be placed.

Inescutcheon

An inescutcheon is a smaller escutcheon that is placed within or superimposed over the main shield of a coat of arms. This may be used in the following cases:

- as a simple mobile charge, for example as borne by the French family of Abbeville, illustrated below; these may also bear other charges upon them, as shown in the arms of the Swedish Collegium of Arms, illustrated below;

- in pretence (as a mark of a hereditary claim, usually by right of marriage), bearing assumed arms over one's own hereditary arms;

- in territorial claim, bearing a monarch's hereditary arms en surtout over the territorial arms of his domains.

-

Escutcheons as mobile charges, as borne by the French family of Abbeville

-

Inescutcheons for style in the arms of the Swedish Collegium of Arms

-

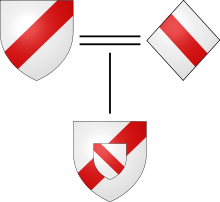

An escutcheon of pretence

-

Inherited arms borne en surtout over territorial arms

Inescutcheons as mobile charges

Inescutcheons may appear in personal and civic armory as simple mobile charges, for example the arms of the House of Mortimer or the noble French family of Abbeville. These mobile charges are of a particular tincture but do not necessarily bear further charges and may appear anywhere on the main escutcheon, their placement being specified in the blazon, if in doubt.

Inescutcheons may also be charged with other mobile charges, such as in the arms of the Swedish Collegium of Arms (illustrated below) which bears the three crowns of Sweden, each upon its own escutcheon upon the field of the main shield. These inescutcheons serve as a basis for including other charges that do not serve as an augmentation or hereditary claim. In this case, the inescutcheons azure allow the three crowns of Sweden to be placed upon a field, thus not only remaining clearly visible but also conforming to the rule of tincture.

Inescutcheon of pretence

Inescutcheons may also be used to bear another's arms in "pretense".[note 1] In English Heraldry the husband of an heraldic heiress, the sole daughter and heiress of an armigerous man (i.e. a lady without any brothers), rather than impaling his wife's paternal arms as is usual, must place her paternal arms in an escutcheon of pretence in the centre of his own shield as a claim ("pretence") to be the new head of his wife's family, now extinct in the male line. In the next generation the arms are quartered by the son.

Use by monarchs and states

A monarch's personal or hereditary arms may be borne on an inescutcheon en surtout over the territorial arms of his/her domains,[note 2] as in the arms of Spain, the coats of arms of the Danish Royal Family members, the greater coat of arms of Sweden, or the arms of Oliver Cromwell as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England (1653–1659). The early Georgian kings of England bore an inescutcheon of the royal arms of Hanover on the arms of the Stuart monarchs of Great Britain, whose territories they now ruled.

Antifeudal variant

Although Americans have produced hundreds of coats of arms for governmental and military agencies since their revolution, the French have refrained from continuing the practice. Their sparse heraldry is based on the pelta, a wide form of shield (or gorget) with a small animal head pointing inward at each end. This is Roman in origin; although not the shape of their classic shield, many brooches of this shape survive from antiquity. A form of pelta appears as a decoration above the head of every official on the Austerlitz table, commissioned by Napoleon for propaganda purposes.

The heraldic pelta appeared officially on the cover of the French passport early in the twentieth century, and in the mid-twentieth century as the coat of arms of the French state in the halls of the United Nations. The Belgian coat of arms uses the same form of shield.

Notes

- ↑ The origin of the inescutcheon of pretense lies in the armorial representation of territorial property. A man coming into lordship by right of his wife would naturally wish to bear the arms associated with that territory, and so would place them inescutcheon over his own; "and arms exclusively of a territorial character have certainly very frequently been placed 'in pretense'." Fox-Davies (1909), p. 539. It is also worth noting that the arms thus borne in pretense represent arms of assumption, while those on the larger shield represent arms of descent.

- ↑ Especially in continental Europe, sovereigns have long held the custom of bearing their hereditary arms in an inescutcheon en surtout over the territorial arms of their dominions. Fox-Davies (1909), p. 541. This custom, coupled with the frequency of European sovereigns ruling over several armigerous territories, may have given rise to the common European form of "quarterly with a heart".

References

- ↑ Boutell, Charles (1914). Fox-Davies, A.C., ed. Handbook to English Heraldry, The (11th Edition ed.). London: Reeves & Turner. p. 33.

- ↑ "Escutcheon". American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2000. Retrieved 2009-03-22.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary

Further reading

- Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles (1909). A Complete Guide to Heraldry. New York: Dodge Pub. Co.