Escherichia coli

| Escherichia coli | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Proteobacteria |

| Class: | Gammaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Enterobacteriales |

| Family: | Enterobacteriaceae |

| Genus: | Escherichia |

| Species: | E. coli |

| Binomial name | |

| Escherichia coli (Migula 1895) Castellani and Chalmers 1919 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Bacillus coli communis Escherich 1885 | |

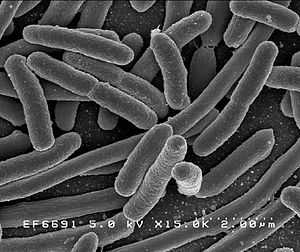

Escherichia coli (/ˌɛʃɨˈrɪkiə ˈkoʊlaɪ/;[1] commonly abbreviated E. coli) is a Gram-negative, facultatively anaerobic, rod-shaped bacterium of the genus Escherichia that is commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms (endotherms).[2] Most E. coli strains are harmless, but some serotypes can cause serious food poisoning in their hosts, and are occasionally responsible for product recalls due to food contamination.[3][4] The harmless strains are part of the normal flora of the gut, and can benefit their hosts by producing vitamin K2,[5] and preventing colonization of the intestine with pathogenic bacteria.[6][7]

E. coli and other facultative anaerobes constitute about 0.1% of gut flora,[8] and fecal–oral transmission is the major route through which pathogenic strains of the bacterium cause disease. Cells are able to survive outside the body for a limited amount of time, which makes them potential indicator organisms to test environmental samples for fecal contamination.[9][10] A growing body of research, though, has examined environmentally persistent E. coli which can survive for extended periods outside of a host.[11]

The bacterium can be grown and cultured easily and inexpensively in a laboratory setting, and has been intensively investigated for over 60 years. E. coli is the most widely studied prokaryotic model organism, and an important species in the fields of biotechnology and microbiology, where it has served as the host organism for the majority of work with recombinant DNA. Under favourable conditions, it takes only 20 minutes to reproduce.[12]

Biology and biochemistry

E. coli is a Gram-negative (bacteria which do not retain crystal violet dye), facultative anaerobic (that makes ATP by aerobic respiration if oxygen is present, but is capable of switching to fermentation or anaerobic respiration if oxygen is absent) and nonsporulating bacteria.[13] Cells are typically rod-shaped, and are about 2.0 micrometers (μm) long and 0.25–1.0 μm in diameter, with a cell volume of 0.6–0.7 μm3.[14][15] It can live on a wide variety of substrates. E. coli uses mixed-acid fermentation in anaerobic conditions, producing lactate, succinate, ethanol, acetate, and carbon dioxide. Since many pathways in mixed-acid fermentation produce hydrogen gas, these pathways require the levels of hydrogen to be low, as is the case when E. coli lives together with hydrogen-consuming organisms, such as methanogens or sulphate-reducing bacteria.[16]

Optimal growth of E. coli occurs at 37 °C (98.6 °F), but some laboratory strains can multiply at temperatures of up to 49 °C.[17] Growth can be driven by aerobic or anaerobic respiration, using a large variety of redox pairs, including the oxidation of pyruvic acid, formic acid, hydrogen, and amino acids, and the reduction of substrates such as oxygen, nitrate, fumarate, dimethyl sulfoxide, and trimethylamine N-oxide.[18]

Strains that possess flagella are motile. The flagella have a peritrichous arrangement.[19]

E. coli and related bacteria possess the ability to transfer DNA via bacterial conjugation, transduction or transformation, which allows genetic material to spread horizontally through an existing population. This process led to the spread of the gene encoding shiga toxin from Shigella to E. coli O157:H7, carried by a bacteriophage.[20]

Diversity

Escherichia coli encompasses an enormous population of bacteria that exhibit a very high degree of both genetic and phenotypic diversity. Genome sequencing of a large number of isolates of E. coli and related bacteria shows that a taxonomic reclassification would be desirable. However, this has not been done, largely due to its medical importance,[21] and E. coli remains one of the most diverse bacterial species: only 20% of the genome is common to all strains.[22]

In fact, from the evolutionary point of view, the members of genus Shigella (S. dysenteriae, S. flexneri, S. boydii, and S. sonnei) should be classified as E. coli strains, a phenomenon termed taxa in disguise.[23] Similarly, other strains of E. coli (e.g. the K-12 strain commonly used in recombinant DNA work) are sufficiently different that they would merit reclassification.

A strain is a subgroup within the species that has unique characteristics that distinguish it from other strains. These differences are often detectable only at the molecular level; however, they may result in changes to the physiology or lifecycle of the bacterium. For example, a strain may gain pathogenic capacity, the ability to use a unique carbon source, the ability to take upon a particular ecological niche, or the ability to resist antimicrobial agents. Different strains of E. coli are often host-specific, making it possible to determine the source of fecal contamination in environmental samples.[9][10] For example, knowing which E. coli strains are present in a water sample allows researchers to make assumptions about whether the contamination originated from a human, another mammal, or a bird.

Serotypes

A common subdivision system of E. coli, but not based on evolutionary relatedness, is by serotype, which is based on major surface antigens (O antigen: part of lipopolysaccharide layer; H: flagellin; K antigen: capsule), e.g. O157:H7).[24] It is, however, common to cite only the serogroup, i.e. the O-antigen. At present, about 190 serogroups are known.[25] The common laboratory strain has a mutation that prevents the formation of an O-antigen and is thus not typeable.

Genome plasticity and evolution

Like all lifeforms, new strains of E. coli evolve through the natural biological processes of mutation, gene duplication, and horizontal gene transfer; in particular, 18% of the genome of the laboratory strain MG1655 was horizontally acquired since the divergence from Salmonella.[26] E. coli K-12 and E. coli B strains are the most frequently used varieties for laboratory purposes. Some strains develop traits that can be harmful to a host animal. These virulent strains typically cause a bout of diarrhea that is unpleasant in healthy adults and is often lethal to children in the developing world.[27] More virulent strains, such as O157:H7, cause serious illness or death in the elderly, the very young, or the immunocompromised.[6][27]

The genera Escherichia and Salmonella diverged around 102 million years ago (credibility interval: 57–176 mya) which coincides with the divergence of their hosts: the former being found in mammals and the latter in birds and reptiles.[28] This was followed by a split of the escherichian ancestor into five species (E. albertii, E. coli, E. fergusonii, E. hermannii, and E. vulneris). The last E. coli ancestor split between 20 and 30 million years ago.[29]

The long-term evolution experiments using E. coli, begun by Richard Lenski in 1988, have allowed direct observation of major evolutionary shifts in the laboratory.[30] In this experiment, one population of E. coli unexpectedly evolved the ability to aerobically metabolize citrate, which is extremely rare in E. coli. As the inability to grow aerobically is normally used as a diagnostic criterion with which to differentiate E. coli from other, closely related bacteria, such as Salmonella, this innovation may mark a speciation event observed in the laboratory.

Neotype strain

E. coli is the type species of the genus (Escherichia) and in turn Escherichia is the type genus of the family Enterobacteriaceae, where the family name does not stem from the genus Enterobacter + "i" (sic.) + "aceae", but from "enterobacterium" + "aceae" (enterobacterium being not a genus, but an alternative trivial name to enteric bacterium).[31][32][33]

The original strain described by Escherich is believed to be lost, consequently a new type strain (neotype) was chosen as a representative: the neotype strain is U5/41T,[34] also known under the deposit names DSM 30083,[35] ATCC 11775,[36] and NCTC 9001,[37] which is pathogenic to chickens and has an O1:K1:H7 serotype.[38] However, in most studies, either O157:H7, K-12 MG1655, or K-12 W3110 were used as a representative E. coli. The genome of the type strain has only lately been sequenced.[34]

Phylogeny of E. coli strains

A large number of strains belonging to this species have been isolated and characterised. In addition to serotype (vide supra), they can be classified according to their phylogeny, i.e. the inferred evolutionary history, as shown below where the species is divided into six groups.[22][39] Particularly the use of whole genome sequences yields highly supported phylogenies. Based on such data, five subspecies of E. coli were distinguished.[34]

The link between phylogenetic distance ("relatedness") and pathology is small,[34] e.g. the O157:H7 serotype strains, which form a clade ("an exclusive group")—group E below—are all enterohaemorragic strains (EHEC), but not all EHEC strains are closely related. In fact, four different species of Shigella are nested among E. coli strains (vide supra), while E. albertii and E. fergusonii are outside of this group. Indeed, all Shigella species were placed within a single subspecies of E. coli in a phylogenomic study that included the type strain,[34] and for this reason an according reclassification is difficult. All commonly used research strains of E. coli belong to group A and are derived mainly from Clifton's K-12 strain (λ⁺ F⁺; O16) and to a lesser degree from d'Herelle's Bacillus coli strain (B strain)(O7).

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Genomics

The first complete DNA sequence of an E. coli genome (laboratory strain K-12 derivative MG1655) was published in 1997. It was found to be a circular DNA molecule 4.6 million base pairs in length, containing 4288 annotated protein-coding genes (organized into 2584 operons), seven ribosomal RNA (rRNA) operons, and 86 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes. Despite having been the subject of intensive genetic analysis for about 40 years, a large number of these genes were previously unknown. The coding density was found to be very high, with a mean distance between genes of only 118 base pairs. The genome was observed to contain a significant number of transposable genetic elements, repeat elements, cryptic prophages, and bacteriophage remnants.[40]

Today, several hundred complete genomic sequences of Escherichia and Shigella species are available. The genome sequence of the type strain of E. coli has been added to this collection not before 2014.[34] Comparison of these sequences shows a remarkable amount of diversity; only about 20% of each genome represents sequences present in every one of the isolates, while around 80% of each genome can vary among isolates.[22] Each individual genome contains between 4,000 and 5,500 genes, but the total number of different genes among all of the sequenced E. coli strains (the pangenome) exceeds 16,000. This very large variety of component genes has been interpreted to mean that two-thirds of the E. coli pangenome originated in other species and arrived through the process of horizontal gene transfer.[41]

Gene nomenclature

Genes in E. coli are usually named by 4-letter acronyms that derive from their function (when known). For instance, recA is named after its role in homologous recombination plus the letter A. Functionally related genes are named recB, recC, recD etc. The proteins are named by uppercase acronyms, e.g. RecA, RecB, etc. When the genome of E. coli was sequenced, all genes were numbered (more or less) in their order on the genome and abbreviated by b numbers, such as b2819 (=recD) etc. The "b" names were created after Fred Blattner who led the genome sequence effort.[42] Another numbering system was introduced with the sequence of another E. coli strain, W3110, which was sequenced in Japan and hence uses numbers starting by JW... (Japanese W3110), e.g. JW2787 (= recD).[43] Hence, recD = b2819 = JW2787. Note, however, that most databases have their own numbering system, e.g. the EcoGene database[44] uses EG10826 for recD. Finally, ECK numbers are specifically used for alleles in the MG1655 strain of E. coli K-12.[44] Complete lists of genes and their synonyms can be obtained from databases such as EcoGene or Uniprot.

Proteomics

Proteome

Several studies have investigated the proteome of E. coli. By 2006, 1,627 (38%) of the 4,237 open reading frames (ORFs) had been identified experimentally.[45]

Interactome

The interactome of E. coli has been studied by affinity purification and mass spectrometry (AP/MS) and by analyzing the binary interactions among its proteins.

Protein complexes. A 2006 study purified 4,339 proteins from cultures of strain K-12 and found interacting partners for 2,667 proteins, many of which had unknown functions at the time.[46] A 2009 study found 5,993 interactions between proteins of the same E. coli strain, though these data showed little overlap with those of the 2006 publication.[47]

Binary interactions. Rajagopala et al. (2014) have carried out systematic yeast two-hybrid screens with most E. coli proteins, and found a total of 2,234 protein-protein interactions.[48] This study also integrated genetic interactions and protein structures and mapped 458 interactions within 227 protein complexes.

Normal microbiota

E. coli belongs to a group of bacteria informally known as "coliforms" that are found in the gastrointestinal tract of warm-blooded animals.[31] E. coli normally colonizes an infant's gastrointestinal tract within 40 hours of birth, arriving with food or water or from the individuals handling the child. In the bowel, E. coli adheres to the mucus of the large intestine. It is the primary facultative anaerobe of the human gastrointestinal tract.[49] (Facultative anaerobes are organisms that can grow in either the presence or absence of oxygen.) As long as these bacteria do not acquire genetic elements encoding for virulence factors, they remain benign commensals.[50]

Therapeutic use

Nonpathogenic E. coli strain Nissle 1917, also known as Mutaflor, and E. coli O83:K24:H31 (known as Colinfant[51]) are used as probiotic agents in medicine, mainly for the treatment of various gastroenterological diseases,[52] including inflammatory bowel disease.[53]

Role in disease

Most E. coli strains do not cause disease,[54] but virulent strains can cause gastroenteritis, urinary tract infections, and neonatal meningitis. In rarer cases, virulent strains are also responsible for hemolytic-uremic syndrome, peritonitis, mastitis, septicemia, and Gram-negative pneumonia.[49]

There is one strain, E.coli #0157:H7, that produces a toxin called the Shiga Toxin (classified as a bioterrorist agent). This toxin causes premature destruction of the red blood cells which then clog the body’s filtering system, the kidneys, causing hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS). This in turn causes strokes due to small clots of blood which lodge in capillaries in the brain. This causes the body parts controlled by this region of the brain to not work properly. In addition, this strain causes the buildup of fluid (since the kidneys do not work) leading to edema around the lungs and legs and arms. This increase in fluid buildup especially around the lungs impedes the functioning of the heart, causing an increase in blood pressure.[55][56][57][58]

Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) is one of the main causes of urinary tract infections.[59] It is part of the normal flora in the gut and can be introduced in many ways. In particular for females, the direction of wiping after defecation (wiping back to front) can lead to fecal contamination of the urogenital orifices. Anal intercourse can also introduce this bacterium into the male urethra, and in switching from anal to vaginal intercourse, the male can also introduce UPEC to the female urogenital system.[59] For more information, see the databases at the end of the article or UPEC pathogenicity.

In May 2011, one E. coli strain, O104:H4, was the subject of a bacterial outbreak that began in Germany. Certain strains of E. coli are a major cause of foodborne illness. The outbreak started when several people in Germany were infected with enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) bacteria, leading to hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS), a medical emergency that requires urgent treatment. The outbreak did not only concern Germany, but also 11 other countries, including regions in North America.[60] On 30 June 2011, the German Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung (BfR) (Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, a federal institute within the German Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection) announced that seeds of fenugreek from Egypt were likely the cause of the EHEC outbreak.[61]

Treatment

The mainstay of treatment is the assessment of dehydration and replacement of fluid and electrolytes. Administration of antibiotics has been shown to shorten the course of illness and duration of excretion of ETEC in adults in endemic areas and in traveller’s diarrhoea. The antibiotic used depends upon susceptibility patterns in the particular geographical region. Currently, the antibiotics of choice are fluoroquinolones or azithromycin, with an emerging role for rifaximin. Oral rifaximin, a semisynthetic rifamycin derivative, is an effective and well-tolerated antibacterial for the management of adults with non-invasive traveller’s diarrhoea. Rifaximin was significantly more effective than placebo and no less effective than ciprofloxacin in reducing the duration of diarrhoea. While rifaximin is effective in patients with E. coli-predominant traveller’s diarrhoea, it appears ineffective in patients infected with inflammatory or invasive enteropathogens.[62]

Prevention

Antibodies against the LT and major CFs of ETEC provide protection against LT-producing ETEC expressing homologous CFs. Oral inactivated vaccines consisting of toxin antigen and whole cells, i.e. the licensed recombinant cholera B subunit (rCTB)-WC cholera vaccine Dukoral and candidate ETEC vaccines have been developed. In different trials, the rCTB-WC cholera vaccine provided high (85–100%) short-term protection. An oral ETEC vaccine consisting of rCTB and formalininactivated E. coli bacteria expressing major CFs has been shown to be safe, immunogenic and effective against severe diarrhoea in American travellers but not against ETEC diarrhoea in young children in Egypt. A modified ETEC vaccine consisting of recombinant E. coli strains overexpressing the major CFs and a more LT-like hybrid toxoid called LCTBA, have been developed and are being tested.[63] [64]

Model organism in life science research

Role in biotechnology

Because of its long history of laboratory culture and ease of manipulation, E. coli plays an important role in modern biological engineering and industrial microbiology.[65] The work of Stanley Norman Cohen and Herbert Boyer in E. coli, using plasmids and restriction enzymes to create recombinant DNA, became a foundation of biotechnology.[66]

E. coli is a very versatile host for the production of heterologous proteins,[67] and various protein expression systems have been developed which allow the production of recombinant proteins in E. coli. Researchers can introduce genes into the microbes using plasmids which permit high level expression of protein, and such protein may be mass-produced in industrial fermentation processes. One of the first useful applications of recombinant DNA technology was the manipulation of E. coli to produce human insulin.[68]

Many proteins previously thought difficult or impossible to be expressed in E. coli in folded form have been successfully expressed in E. coli. For example, proteins with multiple disulphide bonds may be produced in the periplasmic space or in the cytoplasm of mutants rendered sufficiently oxidizing to allow disulphide-bonds to form,[69] while proteins requiring post-translational modification such as glycosylation for stability or function have been expressed using the N-linked glycosylation system of Campylobacter jejuni engineered into E. coli.[70][71][72]

Modified E. coli cells have been used in vaccine development, bioremediation, production of biofuels,[73] lighting, and production of immobilised enzymes.[67][74]

Model organism

E. coli is frequently used as a model organism in microbiology studies. Cultivated strains (e.g. E. coli K12) are well-adapted to the laboratory environment, and, unlike wild-type strains, have lost their ability to thrive in the intestine. Many laboratory strains lose their ability to form biofilms.[75][76] These features protect wild-type strains from antibodies and other chemical attacks, but require a large expenditure of energy and material resources.

In 1946, Joshua Lederberg and Edward Tatum first described the phenomenon known as bacterial conjugation using E. coli as a model bacterium,[77] and it remains the primary model to study conjugation.[78] E. coli was an integral part of the first experiments to understand phage genetics,[79] and early researchers, such as Seymour Benzer, used E. coli and phage T4 to understand the topography of gene structure.[80] Prior to Benzer's research, it was not known whether the gene was a linear structure, or if it had a branching pattern.[81]

E. coli was one of the first organisms to have its genome sequenced; the complete genome of E. coli K12 was published by Science in 1997.[40]

By evaluating the possible combination of nanotechnologies with landscape ecology, complex habitat landscapes can be generated with details at the nanoscale.[82] On such synthetic ecosystems, evolutionary experiments with E. coli have been performed to study the spatial biophysics of adaptation in an island biogeography on-chip.

Studies are also being performed attempting to program E. coli to solve complicated mathematics problems, such as the Hamiltonian path problem.[83]

History

In 1885, the German-Austrian pediatrician Theodor Escherich discovered this organism in the feces of healthy individuals and called it Bacterium coli commune because it is found in the colon and early classifications of prokaryotes placed these in a handful of genera based on their shape and motility (at that time Ernst Haeckel's classification of bacteria in the kingdom Monera was in place.[84][64][85]

Bacterium coli was the type species of the now invalid genus Bacterium when it was revealed that the former type species ("Bacterium triloculare") was missing.[86] Following a revision of Bacterium, it was reclassified as Bacillus coli by Migula in 1895[87] and later reclassified in the newly created genus Escherichia, named after its original discoverer.[88]

See also

- Bacteriological water analysis

- Coliform bacteria

- Contamination control

- Dam dcm strain

- Fecal coliforms

- International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria

- List of bacterial genera named after personal names

- List of strains of Escherichia coli

- Mannan Oligosaccharide based nutritional supplements

- T4 rII system

- 2011 E. coli O104:H4 outbreak

References

- ↑ "coli". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005.

- ↑ Singleton P (1999). Bacteria in Biology, Biotechnology and Medicine (5th ed.). Wiley. pp. 444–454. ISBN 0-471-98880-4.

- ↑ "Escherichia coli". CDC National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases. Retrieved 2012-10-02.

- ↑ Vogt RL, Dippold L (2005). "Escherichia coli O157:H7 outbreak associated with consumption of ground beef, June-July 2002". Public Health Reports (Washington, D.C. : 1974) 120 (2): 174–8. PMC 1497708. PMID 15842119.

- ↑ Bentley R, Meganathan R (Sep 1982). "Biosynthesis of vitamin K (menaquinone) in bacteria". Microbiological Reviews 46 (3): 241–80. PMC 281544. PMID 6127606.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hudault S, Guignot J, Servin AL (Jul 2001). "Escherichia coli strains colonising the gastrointestinal tract protect germfree mice against Salmonella typhimurium infection". Gut 49 (1): 47–55. doi:10.1136/gut.49.1.47. PMC 1728375. PMID 11413110.

- ↑ Reid G, Howard J, Gan BS (Sep 2001). "Can bacterial interference prevent infection?". Trends in Microbiology 9 (9): 424–428. doi:10.1016/S0966-842X(01)02132-1. PMID 11553454.

- ↑ Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Bernstein CN, Purdom E, Dethlefsen L, Sargent M et al. (Jun 2005). "Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora". Science (New York, N.Y.) 308 (5728): 1635–8. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1635E. doi:10.1126/science.1110591. PMC 1395357. PMID 15831718.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Feng P, Weagant S, Grant, M (2002-09-01). "Enumeration of Escherichia coli and the Coliform Bacteria". Bacteriological Analytical Manual (8th ed.). FDA/Center for Food Safety & Applied Nutrition. Retrieved 2007-01-25.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Thompson, Andrea (2007-06-04). "E. coli Thrives in Beach Sands". Live Science. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

- ↑ Ishii S, Sadowsky MJ (2008). "Escherichia coli in the Environment: Implications for Water Quality and Human Health". Microbes and Environments / JSME 23 (2): 101–8. doi:10.1264/jsme2.23.101. PMID 21558695.

- ↑ "Bacteria". Microbiologyonline. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ↑ "E.Coli". Redorbit. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ↑ "Facts about E. coli: dimensions, as discussed in bacteria: Diversity of structure of bacteria: – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2011-06-05.

- ↑ Kubitschek HE (Jan 1990). "Cell volume increase in Escherichia coli after shifts to richer media". Journal of Bacteriology 172 (1): 94–101. PMC 208405. PMID 2403552.

- ↑ Madigan MT, Martinko JM (2006). Brock Biology of microorganisms (11th ed.). Pearson. ISBN 0-13-196893-9.

- ↑ Fotadar U, Zaveloff P, Terracio L (2005). "Growth of Escherichia coli at elevated temperatures". Journal of Basic Microbiology 45 (5): 403–4. doi:10.1002/jobm.200410542. PMID 16187264.

- ↑ Ingledew WJ, Poole RK (Sep 1984). "The respiratory chains of Escherichia coli". Microbiological Reviews 48 (3): 222–71. PMC 373010. PMID 6387427.

- ↑ Darnton NC, Turner L, Rojevsky S, Berg HC (Mar 2007). "On torque and tumbling in swimming Escherichia coli". Journal of Bacteriology 189 (5): 1756–64. doi:10.1128/JB.01501-06. PMC 1855780. PMID 17189361.

- ↑ Brüssow H, Canchaya C, Hardt WD (Sep 2004). "Phages and the evolution of bacterial pathogens: from genomic rearrangements to lysogenic conversion". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews : MMBR 68 (3): 560–602. doi:10.1128/MMBR.68.3.560-602.2004. PMC 515249. PMID 15353570.

- ↑ Krieg, N. R.; Holt, J. G., eds. (1984). Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology 1 (First ed.). Baltimore: The Williams & Wilkins Co. pp. 408–420. ISBN 0-683-04108-8.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Lukjancenko O, Wassenaar TM, Ussery DW (Nov 2010). "Comparison of 61 sequenced Escherichia coli genomes". Microbial Ecology 60 (4): 708–20. doi:10.1007/s00248-010-9717-3. PMC 2974192. PMID 20623278.

- ↑ Lan R, Reeves PR (Sep 2002). "Escherichia coli in disguise: molecular origins of Shigella". Microbes and Infection / Institut Pasteur 4 (11): 1125–32. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(02)01637-4. PMID 12361912.

- ↑ Orskov I, Orskov F, Jann B, Jann K (Sep 1977). "Serology, chemistry, and genetics of O and K antigens of Escherichia coli". Bacteriological Reviews 41 (3): 667–710. PMC 414020. PMID 334154.

- ↑ Stenutz R, Weintraub A, Widmalm G (May 2006). "The structures of Escherichia coli O-polysaccharide antigens". FEMS Microbiology Reviews 30 (3): 382–403. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00016.x. PMID 16594963

- ↑ Lawrence JG, Ochman H (Aug 1998). "Molecular archaeology of the Escherichia coli genome". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 95 (16): 9413–7. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.9413L. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.16.9413. PMC 21352. PMID 9689094.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Nataro JP, Kaper JB (Jan 1998). "Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli". Clinical Microbiology Reviews 11 (1): 142–201. PMC 121379. PMID 9457432.

- ↑ Battistuzzi FU, Feijao A, Hedges SB (Nov 2004). "A genomic timescale of prokaryote evolution: insights into the origin of methanogenesis, phototrophy, and the colonization of land". BMC Evolutionary Biology 4: 44. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-4-44. PMC 533871. PMID 15535883.

- ↑ Lecointre G, Rachdi L, Darlu P, Denamur E (Dec 1998). "Escherichia coli molecular phylogeny using the incongruence length difference test". Molecular Biology and Evolution 15 (12): 1685–95. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025895. PMID 9866203.

- ↑ Bacteria make major evolutionary shift in the lab New Scientist

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (July 26, 2005) [1984 (Williams & Wilkins)]. George M. Garrity, ed. The Gammaproteobacteria. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology 2B (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. p. 1108. ISBN 978-0-387-24144-9. British Library no. GBA561951.

- ↑ Discussion of nomenclature of Enterobacteriaceae entry in LPSN [Euzéby, J.P. (1997). "List of Bacterial Names with Standing in Nomenclature: a folder available on the Internet". Int J Syst Bacteriol 47 (2): 590–2. doi:10.1099/00207713-47-2-590. ISSN 0020-7713. PMID 9103655.]

- ↑ International Bulletin of Bacteriological Nomenclature and Taxonomy 8:73–74 (1958)

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 34.5 Meier-Kolthoff JP, Hahnke RL, Petersen JP, Scheuner CS, Michael VM, Fiebig AF, Rohde CR, Rohde MR, Fartmann BF, Goodwin LA, Chertkov OC, Reddy TR, Pati AP, Ivanova NN, Markowitz VM, Kyrpides NC, Woyke TW, Klenk HP, Göker M (2013). "Complete genome sequence of DSM 30083T, the type strain (U5/41T) of Escherichia coli, and a proposal for delineating subspecies in microbial taxonomy". Standards in Genomic Sciences 9: 2. doi:10.1186/1944-3277-9-2.

- ↑ http://www.dsmz.de/catalogues/details/culture/DSM-30083.html

- ↑ http://www.atcc.org/ATCCAdvancedCatalogSearch/ProductDetails/tabid/452/Default.aspx?ATCCNum=11775&Template=bacteria

- ↑ "Escherichia". bacterio.cict.fr.

- ↑ "Escherichia coli (Migula 1895) Castellani and Chalmers 1919". JCM Catalogue.

- ↑ Brzuszkiewicz E, Thürmer A, Schuldes J, Leimbach A, Liesegang H, Meyer FD et al. (Dec 2011). "Genome sequence analyses of two isolates from the recent Escherichia coli outbreak in Germany reveal the emergence of a new pathotype: Entero-Aggregative-Haemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EAHEC)". Archives of Microbiology 193 (12): 883–91. doi:10.1007/s00203-011-0725-6. PMC 3219860. PMID 21713444.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Blattner FR, Plunkett G, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M et al. (Sep 1997). "The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12". Science (New York, N.Y.) 277 (5331): 1453–62. doi:10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. PMID 9278503.

- ↑ Zhaxybayeva O, Doolittle WF (Apr 2011). "Lateral gene transfer". Current Biology : CB 21 (7): R242–6. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.01.045. PMID 21481756.

- ↑ Blattner FR, Plunkett G, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M et al. (Sep 1997). "The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12". Science (New York, N.Y.) 277 (5331): 1453–1462. doi:10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. PMID 9278503.

- ↑ Hayashi K, Morooka N, Yamamoto Y, Fujita K, Isono K, Choi S et al. (2006). "Highly accurate genome sequences of Escherichia coli K-12 strains MG1655 and W3110". Molecular Systems Biology 2: 2006.0007. doi:10.1038/msb4100049. PMC 1681481. PMID 16738553.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Zhou J, Rudd KE (Jan 2013). "EcoGene 3.0". Nucleic Acids Research 41 (Database issue): D613–24. doi:10.1093/nar/gks1235. PMC 3531124. PMID 23197660.

- ↑ Han MJ, Lee SY (Jun 2006). "The Escherichia coli proteome: past, present, and future prospects". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews : MMBR 70 (2): 362–439. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00036-05. PMC 1489533. PMID 16760308.

- ↑ Arifuzzaman M, Maeda M, Itoh A, Nishikata K, Takita C, Saito R et al. (May 2006). "Large-scale identification of protein-protein interaction of Escherichia coli K-12". Genome Research 16 (5): 686–91. doi:10.1101/gr.4527806. PMC 1457052. PMID 16606699.

- ↑ Hu P, Janga SC, Babu M, Díaz-Mejía JJ, Butland G, Yang W et al. (Apr 2009). Levchenko A, ed. "Global functional atlas of Escherichia coli encompassing previously uncharacterized proteins". PLoS Biology 7 (4): e96. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000096. PMC 2672614. PMID 19402753.

- ↑ Rajagopala SV, Sikorski P, Kumar A, Mosca R, Vlasblom J, Arnold R et al. (Mar 2014). "The binary protein-protein interaction landscape of Escherichia coli". Nature Biotechnology 32 (3): 285–90. doi:10.1038/nbt.2831. PMID 24561554.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Todar, K. "Pathogenic E. coli". Online Textbook of Bacteriology. University of Wisconsin–Madison Department of Bacteriology. Retrieved 2007-11-30.

- ↑ Evans Jr., Doyle J.; Dolores G. Evans. "Escherichia Coli". Medical Microbiology, 4th edition. The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. Archived from the original on 2007-11-02. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ↑ Lodinová-Zádníková R, Cukrowska B, Tlaskalova-Hogenova H (Jul 2003). "Oral administration of probiotic Escherichia coli after birth reduces frequency of allergies and repeated infections later in life (after 10 and 20 years)". International Archives of Allergy and Immunology 131 (3): 209–11. doi:10.1159/000071488. PMID 12876412.

- ↑ Grozdanov L, Raasch C, Schulze J, Sonnenborn U, Gottschalk G, Hacker J et al. (Aug 2004). "Analysis of the genome structure of the nonpathogenic probiotic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917". Journal of Bacteriology 186 (16): 5432–41. doi:10.1128/JB.186.16.5432-5441.2004. PMC 490877. PMID 15292145.

- ↑ Kamada N, Inoue N, Hisamatsu T, Okamoto S, Matsuoka K, Sato T et al. (May 2005). "Nonpathogenic Escherichia coli strain Nissle1917 prevents murine acute and chronic colitis". Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 11 (5): 455–63. doi:10.1097/01.MIB.0000158158.55955.de. PMID 15867585.

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/e-coli/basics/definition/con-20032105

- ↑ "E. Coli Food Poisoning." About. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Dec. 2014. <http://www.about-ecoli.com/>.

- ↑ "Lung Congestion." TheFreeDictionary.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Dec. 2014. <http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Lung+Congestion>.

- ↑ "Pulmonary Edema: Get the Facts on Treatment and Symptoms." MedicineNet. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Dec. 2014. <http://www.medicinenet.com/pulmonary_edema/article.htm>.

- ↑ Staff, Mayo Clinic. "Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS)." Mayo Clinic. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 03 July 2013. Web. 13 Dec. 2014. <http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/hemolytic-uremic-syndrome/DS00876>.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 "Uropathogenic Escherichia coli: The Pre-Eminent Urinary Tract Infection Pathogen". Nova publishers. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ↑ Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia Coli (EHEC) outbreak in Germany

- ↑ "Samen von Bockshornklee mit hoher Wahrscheinlichkeit für EHEC O104:H4 Ausbruch verantwortlich in English: Fenugreek seeds with high probability for EHEC O104: H4 responsible outbreak" (PDF) (in German). Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung (BfR) in English: Federal Institute for Risk Assessment. 30 June 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ↑ Al-Abri SS, Beeching NJ, Nye FJ (June 2005). "Traveller's diarrhoea". The Lancet Infectious Diseases 5 (6): 349–360. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70139-0.

- ↑ Svennerholm AM (Feb 2011). "From cholera to enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) vaccine development". The Indian Journal of Medical Research 133: 188–96. PMID 21415493.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Farrar J, Hotez P, Junghanss T, Kang G, Lalloo D, White NJ, eds. (2013). Manson's Tropical Diseases (23rd ed.). Oxford: Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 9780702053061.

- ↑ Lee SY (Mar 1996). "High cell-density culture of Escherichia coli". Trends in Biotechnology 14 (3): 98–105. doi:10.1016/0167-7799(96)80930-9. PMID 8867291.

- ↑ Russo E (Jan 2003). "The birth of biotechnology". Nature 421 (6921): 456–457. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..456R. doi:10.1038/nj6921-456a. PMID 12540923.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Cornelis P (Oct 2000). "Expressing genes in different Escherichia coli compartments". Current Opinion in Biotechnology 11 (5): 450–454. doi:10.1016/S0958-1669(00)00131-2. PMID 11024362.

- ↑ Tof, Ilanit (1994). "Recombinant DNA Technology in the Synthesis of Human Insulin". Little Tree Pty. Ltd. Retrieved 2007-11-30.

- ↑ Bessette PH, Aslund F, Beckwith J, Georgiou G (Nov 1999). "Efficient folding of proteins with multiple disulfide bonds in the Escherichia coli cytoplasm". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 96 (24): 13703–8. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9613703B. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.24.13703. PMC 24128. PMID 10570136.

- ↑ Ihssen J, Kowarik M, Dilettoso S, Tanner C, Wacker M, Thöny-Meyer L (2010). "Production of glycoprotein vaccines in Escherichia coli". Microbial Cell Factories 9 (61): 494–7. doi:10.1186/1475-2859-9-61. PMC 2927510. PMID 20701771.

- ↑ Wacker M, Linton D, Hitchen PG, Nita-Lazar M, Haslam SM, North SJ et al. (Nov 2002). "N-linked glycosylation in Campylobacter jejuni and its functional transfer into E. coli". Science (New York, N.Y.) 298 (5599): 1790–1793. doi:10.1126/science.298.5599.1790. PMID 12459590.

- ↑ Huang CJ, Lin H, Yang X (Mar 2012). "Industrial production of recombinant therapeutics in Escherichia coli and its recent advancements". Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology 39 (3): 383–99. doi:10.1007/s10295-011-1082-9. PMID 22252444.

- ↑ Summers, Rebecca (24 April 2013) Bacteria churn out first ever petrol-like biofuel New Scientist, Retrieved 27 April 2013

- ↑ Nic Halverson (August 15, 2013). "Bacteria-Powered Light Bulb Is Electricity-Free".

- ↑ Fux CA, Shirtliff M, Stoodley P, Costerton JW (Feb 2005). "Can laboratory reference strains mirror "real-world" pathogenesis?". Trends in Microbiology 13 (2): 58–63. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2004.11.001. PMID 15680764.

- ↑ Vidal O, Longin R, Prigent-Combaret C, Dorel C, Hooreman M, Lejeune P (May 1998). "Isolation of an Escherichia coli K-12 mutant strain able to form biofilms on inert surfaces: involvement of a new ompR allele that increases curli expression". Journal of Bacteriology 180 (9): 2442–9. PMC 107187. PMID 9573197.

- ↑ Lederberg, Joshua; E.L. Tatum (October 19, 1946). "Gene recombination in E. coli" (PDF). Nature 158 (4016): 558. Bibcode:1946Natur.158..558L. doi:10.1038/158558a0. Source: National Library of Medicine – The Joshua Lederberg Papers

- ↑ Biological Activity of Crystal. p. 169.

- ↑ "The Phage Course – Origins". Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. 2006. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

- ↑ Benzer S (Mar 1961). "ON THE TOPOGRAPHY OF THE GENETIC FINE STRUCTURE". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 47 (3): 403–15. Bibcode:1961PNAS...47..403B. doi:10.1073/pnas.47.3.403. PMC 221592. PMID 16590840.

- ↑ "Facts about E.Coli". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ↑ Keymer JE, Galajda P, Muldoon C, Park S, Austin RH (Nov 2006). "Bacterial metapopulations in nanofabricated landscapes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 (46): 17290–5. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10317290K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607971103. PMC 1635019. PMID 17090676.

- ↑ Baumgardner J, Acker K, Adefuye O, Crowley ST, Deloache W, Dickson JO et al. (July 24, 2009). "Solving a Hamiltonian Path Problem with a bacterial computer". Journal of Biological Engineering (J Biol Eng. 2009; 3: 11.) 3: 11. doi:10.1186/1754-1611-3-11. PMC 2723075. PMID 19630940.

- ↑ Haeckel, Ernst (1867). Generelle Morphologie der Organismen. Reimer, Berlin. ISBN 1-144-00186-2.

- ↑ Escherich T (1885). "Die Darmbakterien des Neugeborenen und Säuglinge". Fortschr. Med. 3: 515–522.

- ↑ Breed RS, Conn HJ (May 1936). "The Status of the Generic Term Bacterium Ehrenberg 1828". Journal of Bacteriology 31 (5): 517–8. PMC 543738. PMID 16559906.

- ↑ Migula W (1895). "Bacteriaceae (Stabchenbacterien)". In Engerl A, Prantl K. Die Naturlichen Pfanzenfamilien, W. Engelmann, Leipzig, Teil I, Abteilung Ia,. pp. 20–30.

- ↑ Castellani A, Chalmers AJ (1919). Manual of Tropical Medicine (3rd ed.). New York: Williams Wood and Co.

Further reading

- Jann K, Jann B (Jul 1992). "Capsules of Escherichia coli, expression and biological significance". Canadian Journal of Microbiology 38 (7): 705–710. doi:10.1139/m92-116. PMID 1393836.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Escherichia coli |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Escherichia coli. |

- Photo Blog post of Escherichia Coli

- E. coli Vs Organic Farming

- E. coli: Protecting yourself and your family from a sometimes deadly bacterium

- E. coli statistics

- Spinach and E. coli Outbreak – U.S. FDA

- E. coli Outbreak From Fresh Spinach – U.S. CDC

- Current research on Escherichia coli at the Norwich Research Park

- E. coli gas production from glucose video demonstration

- The correct way to write E. coli

E. coli databases

- Bacteriome E. coli interaction database

- coliBASE (subset of the comparative genomics database xBASE)

- EcoGene (genome database and website dedicated to Escherichia coli K-12 substrain MG1655)

- EcoSal Continually updated Web resource based on the classic ASM Press publication Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology

- ECODAB The structure of the O-antigens that form the basis of the serological classification of E. coli

- Coli Genetic Stock Center Strains and genetic information on E. coli K-12

- EcoCyc – literature-based curation of the entire genome, and of transcriptional regulation, transporters, and metabolic pathways

- PortEco (formerly EcoliHub) – NIH-funded comprehensive data resource for E. coli K-12 and its phage, plasmids, and mobile genetic elements

- EcoliWiki is the community annotation component of PortEco

- RegulonDB RegulonDB is a model of the complex regulation of transcription initiation or regulatory network of the cell E. coli K-12.

- Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC)

General databases with E. coli-related information

- 5S rRNA Database Information on nucleotide sequences of 5S rRNAs and their genes

- ACLAME A CLAssification of Mobile genetic Elements

- AlignACE Matrices that search for additional binding sites in the E. coli genomic sequence

- ArrayExpress Database of functional genomics experiments

- ASAP Comprehensive genome information for several enteric bacteria with community annotation

- BioGPS Gene portal hub

- BRENDA Comprehensive Enzyme Information System

- BSGI Bacterial Structural Genomics Initiative

- CATH Protein Structure Classification

- CBS Genome Atlas

- CDD Conserved Domain Database

- CIBEX Center for Information Biology Gene Expression Database

- COGs

| ||||||