Erwin Schrödinger

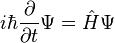

Erwin Rudolf Josef Alexander Schrödinger (German: [ˈɛʁviːn ˈʃʁøːdɪŋɐ]; 12 August 1887 – 4 January 1961), sometimes written as Erwin Schrodinger or Erwin Schroedinger, was a Nobel Prize-winning Austrian physicist who developed a number of fundamental results in the field of quantum theory, which formed the basis of wave mechanics: he formulated the wave equation (stationary and time-dependent Schrödinger equation) and revealed the identity of his development of the formalism and matrix mechanics. Schrödinger proposed an original interpretation of the physical meaning of the wave function.

In addition, he was the author of many works in various fields of physics: statistical mechanics and thermodynamics, physics of dielectrics, colour theory, electrodynamics, general relativity, and cosmology, and he made several attempts to construct a unified field theory. In his book What Is Life? Schrödinger addressed the problems of genetics, looking at the phenomenon of life from the point of view of physics. He paid great attention to the philosophical aspects of science, ancient and oriental philosophical concepts, ethics, and religion.[2] He also wrote on philosophy and theoretical biology.

He is also known for his "Schrödinger's cat" thought-experiment.

Biography

Early years

On 12 August 1887, Schrödinger was born in Vienna, Austria, to Rudolf Schrödinger (cerecloth producer, botanist) and Georgine Emilia Brenda (daughter of Alexander Bauer, Professor of Chemistry, Technische Hochschule Vienna). He was their only child.

His mother was half Austrian and half English; his father was Catholic and his mother was Lutheran. Despite being raised in a religious household, he called himself an atheist.[3][4] However, he had strong interests in Eastern religions, pantheism and used religious symbolism in his works. He also believed his scientific work was an approach to the godhead, albeit in a metaphorical sense.[5][6]

He was also able to learn English outside of school, as his maternal grandmother was British.[7] Between 1906 and 1910 Schrödinger studied in Vienna under Franz S. Exner (1849–1926) and Friedrich Hasenöhrl (1874–1915). He also conducted experimental work with Karl Wilhelm Friedrich "Fritz" Kohlrausch.

In 1911, Schrödinger became an assistant to Exner. At an early age, Schrödinger was strongly influenced by Arthur Schopenhauer. As a result of his extensive reading of Schopenhauer's works, he became deeply interested throughout his life in colour theory and philosophy. In his lecture "Mind and Matter", he said that "The world extended in space and time is but our representation." This is a repetition of the first words of Schopenhauer's main work.

Middle years

In 1914 Erwin Schrödinger achieved Habilitation (venia legendi). Between 1914 and 1918 he participated in war work as a commissioned officer in the Austrian fortress artillery (Gorizia, Duino, Sistiana, Prosecco, Vienna). In 1920 he became the assistant to Max Wien, in Jena, and in September 1920 he attained the position of ao. Prof. (ausserordentlicher Professor), roughly equivalent to Reader (UK) or associate professor (US), in Stuttgart. In 1921, he became o. Prof. (ordentlicher Professor, i.e. full professor), in Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland).

In 1921, he moved to the University of Zürich. In 1927, he succeeded Max Planck at the Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin. In 1934, however, Schrödinger decided to leave Germany; he disliked the Nazis' anti-semitism. He became a Fellow of Magdalen College at the University of Oxford. Soon after he arrived, he received the Nobel Prize together with Paul Dirac. His position at Oxford did not work out well; his unconventional domestic arrangements, sharing living quarters with two women[8] was not met with acceptance. In 1934, Schrödinger lectured at Princeton University; he was offered a permanent position there, but did not accept it. Again, his wish to set up house with his wife and his mistress may have created a problem.[9] He had the prospect of a position at the University of Edinburgh but visa delays occurred, and in the end he took up a position at the University of Graz in Austria in 1936.

In the midst of these tenure issues in 1935, after extensive correspondence with Albert Einstein, he proposed what is now called the Schrödinger's cat thought experiment.

Later years

In 1938, after the Anschluss, Schrödinger had problems because of his flight from Germany in 1933 and his known opposition to Nazism. He issued a statement recanting this opposition (he later regretted doing so and personally apologized to Einstein). However, this did not fully appease the new dispensation and the University of Graz dismissed him from his job for political unreliability. He suffered harassment and received instructions not to leave the country, but he and his wife fled to Italy. From there, he went to visiting positions in Oxford and Ghent University.

In the same year he received a personal invitation from Ireland's Taoiseach, Éamon de Valera, to reside in Ireland and agree to help establish an Institute for Advanced Studies in Dublin.[10] He moved to Clontarf, Dublin, became the Director of the School for Theoretical Physics in 1940 and remained there for 17 years. He became a naturalized Irish citizen in 1948, but retained his Austrian citizenship. He wrote about 50 further publications on various topics, including his explorations of unified field theory.

In 1944, he wrote What Is Life?, which contains a discussion of negentropy and the concept of a complex molecule with the genetic code for living organisms. According to James D. Watson's memoir, DNA, the Secret of Life, Schrödinger's book gave Watson the inspiration to research the gene, which led to the discovery of the DNA double helix structure in 1953. Similarly, Francis Crick, in his autobiographical book What Mad Pursuit, described how he was influenced by Schrödinger's speculations about how genetic information might be stored in molecules. However, the geneticist and 1946 Nobel-prize winner H.J. Muller had in his 1922 article "Variation due to Change in the Individual Gene"[11] already laid out all the basic properties of the heredity molecule that Schrödinger derives from first principles in What Is Life?, properties which Muller refined in his 1929 article "The Gene As The Basis of Life"[12] and further clarified during the 1930s, long before the publication of What Is Life?.[13]

Schrödinger stayed in Dublin until retiring in 1955. He had a lifelong interest in the Vedanta philosophy of Hinduism, which influenced his speculations at the close of What Is Life? about the possibility that individual consciousness is only a manifestation of a unitary consciousness pervading the universe.[14] A manuscript "Fragment From An Unpublished Dialogue of Galileo" from this time recently resurfaced at The King's Hospital boarding school, Dublin[15] after it was written for the School's 1955 edition of their Blue Coat to celebrate his leaving of Dublin to take up his appointment as Chair of Physics at the University of Vienna.

In 1956, he returned to Vienna (chair ad personam). At an important lecture during the World Energy Conference he refused to speak on nuclear energy because of his skepticism about it and gave a philosophical lecture instead. During this period Schrödinger turned from mainstream quantum mechanics' definition of wave–particle duality and promoted the wave idea alone, causing much controversy.

Personal life

On 6 April 1920, Schrödinger married Annemarie (Anny) Bertel.[16]

Schrödinger suffered from tuberculosis and several times in the 1920s stayed at a sanatorium in Arosa. It was there that he formulated his wave equation.[17]

On 4 January 1961, Schrödinger died in Vienna at the age of 73 of tuberculosis. He left Anny a widow, and was buried in Alpbach, Austria, in a Catholic cemetery. Although he was not Catholic, the priest in charge of the cemetery permitted the burial after learning Schrödinger was a member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences.[18] His wife, Anny (born 3 December 1896) died on 3 October 1965.

Scientific activities

Early activities

Early in his life, Schrödinger experimented in the fields of electrical engineering, atmospheric electricity, and atmospheric radioactivity; he usually worked with his former teacher Franz Exner. He also studied vibrational theory, the theory of Brownian movement, and mathematical statistics. In 1912, at the request of the editors of the Handbook of Electricity and Magnetism, Schrödinger wrote an article titled Dieelectrism. That same year, Schrödinger gave a theoretical estimate of the probable height distribution of radioactive substances, which is required to explain the observed radioactivity of the atmosphere, and in August 1913 executed several experiments in Zeehame that confirmed his theoretical estimate and those of Victor Franz Hess. For this work, Schrödinger was awarded the 1920 Haytingera Prize (Haitinger-Preis) of the Austrian Academy of Sciences.[19] Other experimental studies conducted by the young researcher in 1914 were checking formulas for capillary pressure in gas bubbles and the study of the properties of soft beta-radiation appearing in the fall of gamma rays on the surface of metal. The last work he performed together with his friend Fritz Kohlrausch. In 1919, Schrödinger performed his last physical experiment on coherent light and subsequently focused on theoretical studies.

Quantum mechanics

New quantum theory

In the first years of his career Schrödinger became acquainted with the ideas of quantum theory, developed in the works of Max Planck, Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, Arnold Sommerfeld, and others. This knowledge helped him work on some problems in theoretical physics, but the Austrian scientist at the time was not yet ready to part with the traditional methods of classical physics.

The first publications of Schrödinger about atomic theory and the theory of spectra began to emerge only from the beginning of the 1920s, after his personal acquaintance with Sommerfeld and Wolfgang Pauli and his move to Germany. In January 1921, Schrödinger finished his first article on this subject, about the framework of the Bohr-Sommerfeld effect of the interaction of electrons on some features of the spectra of the alkali metals. Of particular interest to him was the introduction of relativistic considerations in quantum theory. In autumn 1922 he analyzed the electron orbits in an atom from a geometric point of view, using methods developed by the mathematician Hermann Weyl (1885–1955). This work, in which it was shown that quantum orbits are associated with certain geometric properties, was an important step in predicting some of the features of wave mechanics. Earlier in the same year he created the Schrödinger equation of the relativistic Doppler effect for spectral lines, based on the hypothesis of light quanta and considerations of energy and momentum. He liked the idea of his teacher Exner on the statistical nature of the conservation laws, so he enthusiastically embraced the articles of Bohr, Kramers, and Slater, which suggested the possibility of violation of these laws in individual atomic processes (for example, in the process of emission of radiation). Despite the fact that the experiments of Hans Geiger and Walther Bothe soon cast doubt on this, the idea of energy as a statistical concept was a lifelong attraction for Schrödinger and he discussed it in some reports and publications.[20]

Creation of wave mechanics

In January 1926, Schrödinger published in Annalen der Physik the paper "Quantisierung als Eigenwertproblem"[21] [tr. Quantization as an Eigenvalue Problem] on wave mechanics and presented what is now known as the Schrödinger equation. In this paper, he gave a "derivation" of the wave equation for time-independent systems and showed that it gave the correct energy eigenvalues for a hydrogen-like atom. This paper has been universally celebrated as one of the most important achievements of the twentieth century and created a revolution in quantum mechanics and indeed of all physics and chemistry. A second paper was submitted just four weeks later that solved the quantum harmonic oscillator, rigid rotor, and diatomic molecule problems and gave a new derivation of the Schrödinger equation. A third paper, published in May, showed the equivalence of his approach to that of Heisenberg and gave the treatment of the Stark effect. A fourth paper in this series showed how to treat problems in which the system changes with time, as in scattering problems. In this paper he introduced a complex solution to the Wave equation in order to prevent the occurrence of a fourth order differential equation, and this was arguably the moment when quantum mechanics switched from real to complex numbers, never to return. These papers were his central achievement and were at once recognized as having great significance by the physics community.

Schrödinger was not entirely comfortable with the implications of quantum theory. Schrödinger wrote about the probability interpretation of quantum mechanics, saying: "I don't like it, and I'm sorry I ever had anything to do with it."[22]

Work on a Unified Field Theory

Following his work on quantum mechanics, Schrödinger devoted considerable effort to working on a Unified Field Theory that would unite gravity, electromagnetism, and nuclear forces within the basic framework of General Relativity, doing the work with an extended correspondence with Albert Einstein.[23] In 1947, he announced a result, "Affine Field Theory,"[24] in a talk at the Royal Irish Academy, but the announcement was criticized by Einstein as "preliminary" and failed to lead to the desired unified theory.[23] Following the failure of his attempt at unification, Schrödinger gave up his work on unification and turned to other topics.

Colour

One of Schrödinger's lesser-known areas of scientific contribution was his work on colour, colour perception, and colorimetry (Farbenmetrik). In 1920, he published three papers in this area:

- "Theorie der Pigmente von größter Leuchtkraft", Annalen der Physik, (4), 62, (1920), 603–22 (Theory of Pigments with Highest Luminosity)

- "Grundlinien einer Theorie der Farbenmetrik im Tagessehen", Annalen der Physik, (4), 63, (1920), 397–456; 481–520 (Outline of a theory of colour measurement for daylight vision)

- "Farbenmetrik", Zeitschrift für Physik, 1, (1920), 459–66 (Colour measurement).

The second of these is available in English as "Outline of a Theory of Colour Measurement for Daylight Vision" in Sources of Colour Science, Ed. David L. MacAdam, The MIT Press (1970), 134–82.

Legacy

The philosophical issues raised by Schrödinger's cat are still debated today and remain his most enduring legacy in popular science, while Schrödinger's equation is his most enduring legacy at a more technical level. To this day, Schrödinger is known as the father of quantum mechanics. The large crater Schrödinger, on the far side of the Moon, is named after him. The Erwin Schrödinger International Institute for Mathematical Physics was established in Vienna in 1993.

Schrödinger's portrait was the main feature of the design of the 1983–97 Austrian 1000-Schilling banknote, the second-highest denomination.

A building is named after him at the University of Limerick, in Limerick, Ireland,[25] as is the 'Erwin Schrödinger Zentrum' at Adlershof in Berlin.[26]

Schrödinger's 126th birthday anniversary was celebrated with a Google Doodle.[27][28]

Honors and awards

- Nobel Prize for Physics (1933) – for the formulation of the Schrödinger equation

- Max Planck Medal (1937)

- Erwin Schrödinger Prize of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (1956)

- Austrian Decoration for Science and Art (1957)

Published works

- The List of Erwin Schrödinger's publications, compiled by Auguste Dick, Gabriele Kerber, Wolfgang Kerber and Karl von Meyenn's Erwin Schrödinger: Publications

- Science and the human temperament Allen & Unwin (1935), translated and introduced by James Murphy, with a foreword by Ernest Rutherford

- Nature and the Greeks and Science and Humanism Cambridge University Press (1996) ISBN 0-521-57550-8.

- The interpretation of Quantum Mechanics Ox Bow Press (1995) ISBN 1-881987-09-4.

- Statistical Thermodynamics Dover Publications (1989) ISBN 0-486-66101-6.

- Collected papers Friedr. Vieweg & Sohn (1984) ISBN 3-7001-0573-8.

- My View of the World Ox Bow Press (1983) ISBN 0-918024-30-7.

- Expanding Universes Cambridge University Press (1956).

- Space-Time Structure Cambridge University Press (1950) ISBN 0-521-31520-4.[29]

- What Is Life? Macmillan (1944).

- What Is Life? & Mind and Matter Cambridge University Press (1974) ISBN 0-521-09397-X.

See also

- List of Austrian scientists

- List of Austrians

- List of things named after Erwin Schrödinger

- Quantum Aspects of Life

- Biophysics

References

- ↑ Moore, Walter J (29 May 1992). Schrödinger, life and thought. Cambridge University Press. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-0-521-43767-7. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ↑ Heitler, W. (1961). "Erwin Schrodinger. 1887–1961". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society 7: 221–226. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1961.0017. JSTOR 769408.

- ↑ Walter J. Moore (1994). A Life of Erwin Schrödinger. Cambridge University Press. pp. 289–290. ISBN 9780521469340.

In one respect, however, he is not a romantic: he does not idealize the person of the beloved, his highest praise is to consider her his equal. "When you feel your own equal in the body of a beautiful woman, just as ready to forget the world for you as you for her – oh my good Lord – who can describe what happiness then. You can live it, now and again – you cannot speak of it." Of course, he does speak of it, and almost always with religious imagery. Yet at this time he also wrote, "By the way, I never realized that to be nonbelieving, to be an atheist, was a thing to be proud of. It went without saying as it were." And in another place at about this same time: "Our creed is indeed a queer creed. You others, Christians (and similar people), consider our ethics much inferior, indeed abominable. There is that little difference. We adhere to ours in practice, you don't."

- ↑ Andrea Diem-Lane. Spooky Physics. MSAC Philosophy Group. p. 42. ISBN 9781565430808.

- ↑ Moore, Walter (1989). Schrödinger: Life and Thought. ISBN 0-521-43767-9.

He rejected traditional religious beliefs (Jewish, Christian, and Islamic) not on the basis of any reasoned argument, nor even with an expression of emotional antipathy, for he loved to use religious expressions and metaphors, but simply by saying that they are naive.

- ↑ Walter J. Moore (1992). Schrödinger: Life and Thought. Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780521437677.

He claimed to be an atheist, but he always used religious symbolism and believed his scientific work was an approach to the godhead.

- ↑ Hoffman, D. (1987). Эрвин Шрёдингер. Мир. pp. 13–17.

- ↑ Walter J. Moore. Schrödinger, life and thought, 278 ff.

- ↑ Deutsche Biographie

- ↑ Daugherty, Brian. "Brief Chronology". Erwin Schrödinger. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ↑ American Naturalist 56 (1922)

- ↑ Proceedings of the International Congress of Plant Sciences 1 (1929)

- ↑ In Pursuit of the Gene. From Darwin to DNA – By James Schwartz. Harvard University Press, 2008

- ↑ My View of the World Erwin Schrödinger chapter iv. What Is life? the physical aspect of the living cell & Mind and matter – By Erwin Schrodinger

- ↑ http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/ireland/2012/0418/1224314875355.html

- ↑ Schrödinger: Life and Thought by Walter John Moore, Cambridge University Press 1992 ISBN 0-521-43767-9, discusses Schrödinger's unconventional relationships, including his affair with Hildegunde March, in chapters seven and eight, "Berlin" and "Exile in Oxford".

- ↑ Moore, Walter J (9 January 1926). Schrödinger by Walter J. Moore: Christmas at Arosa. Books.google.co.uk. ISBN 978-0-521-43767-7. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ↑ Walter J. Moore (1992). Schrödinger: Life and Thought. Cambridge University Press. p. 482. ISBN 9780521437677.

There was some problem about burial in the churchyard since Erwin was not a Catholic, but the priest relented when informed that he was a member in good standing of the Papal Academy, and a plot was made available at the edge of the Friedhof.

- ↑ Mehra, J. and Rechenberg, H. (1987) Erwin Schrödinger and the Rise of Wave Mechanics. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-95179-9

- ↑ The Conceptual Development of Quantum Mechanics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1966; 2nd ed: New York: American Institute of Physics, 1989. ISBN 0-88318-617-9

- ↑ Schrodinger, Erwin (1926). "Quantisierung als Eigenwertproblem". Annalen der Phys 384 (4): 273–376. Bibcode:1926AnP...384..361S. doi:10.1002/andp.19263840404. Archived from the original on 14 March 2006. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ↑ "A Quantum Sampler". The New York Times. 26 December 2005.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Halpern, Paul, Battle of the Nobel Laureates, April 2015 (accessed 2 April 2015).

- ↑ Schrodinger, E., Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Vol. 51A (1947) p. 163. Available here (accessed 2 April 2015)

- ↑ "Buildings at A Glance". University of Limerick. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ↑ "EYCN Delegates Assembly". 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ↑ "Physicist Erwin Schrödinger's Google doodle marks quantum mechanics work". The Guardian. 13 August 2013. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ↑ Williams, Rob (12 August 2013). "Google Doodle honours quantum physicist Erwin Schrödinger (and his theoretical cat)". The Independent (London). Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ↑ Taub, A. (1951). "Review: Space-time structure by Erwin Schrödinger" (PDF). Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 57 (3): 205.

Sources

- John Gribbin (2012), Erwin Schrödinger and the Quantum Revolution, Bantam Press.

- Medawar, Jean; Pyke, David (2012). Hitler's Gift : The True Story of the Scientists Expelled by the Nazi Regime (Paperback). New York: Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61145-709-4.

- Moore, Walter J (29 May 1992). "Schrödinger, life and thought". Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43767-7. Retrieved 7 November 2011..

- Moore, Walter J (2003). A Life of Erwin Schrödinger (Canto ed.). Cambridge University Press. Bibcode:1994les..book.....M. ISBN 0-521-46934-1..

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Erwin Schrödinger. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Erwin Schrödinger |

- Erwin Schrödinger on an Austrian banknote.

- 1927 Solvay video with opening shot of Schrödinger on YouTube

- "biographie" (in German) or

- "Biography from the Austrian Central Library for Physics" (in English)

- Encyclopaedia Britannica article on Erwin Schrodinger

- "Deutsche Biographie"

- Nobel Lectures, Physics 1922–1941, "Erwin Schrödinger Biography" from NobelPrize.org

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Erwin Schrödinger", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Vallabhan, C. P. Girija, "Indian influences on Quantum Dynamics" [ed. Schrödinger's interest in Vedanta]

- Schrödinger Medal of the World Association of Theoretically Oriented Chemists (WATOC)

- The Discovery of New Productive Forms of Atomic Theory Nobel Banquet speech (in German)

- Annotated bibliography for Erwin Schrodinger from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- (Italian) Critical interdisciplinary review of Schrödinger's "What Is life?"

| ||||||||

|