Erotic art

Erotic art covers any artistic work that is intended to evoke erotic arousal or that depicts scenes of love-making. It includes paintings, engravings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, music and writing.

Definition

Defining erotic art is difficult since perceptions of both what is erotic and what is art fluctuate. A sculpture of a phallus in some African cultures may be considered a traditional symbol of potency though not overtly erotic.

In addition, a distinction is often made between erotic art and pornography (which also depicts scenes of love-making and is intended to evoke erotic arousal, but is not usually considered art). The distinction may lie in intent and message; erotic art would be items intended as pieces of art, encapturing formal elements of art, and drawing on other historical artworks. Pornography may also use these tools, but is primarily intended to arouse one sexually. Nevertheless, these elements of distinction are highly subjective.

For instance, Justice Potter Stewart of the Supreme Court of the United States, in attempting to explain "hard-core" pornography, or what is obscene, famously wrote, "I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced ... [b]ut I know it when I see it ..."[1]

Historical

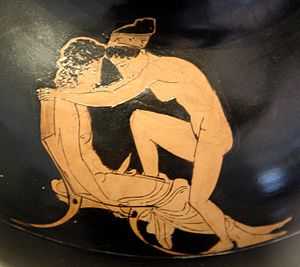

Among the oldest surviving examples of erotic depictions are Paleolithic cave paintings and carvings, but many cultures have created erotic art. The ancient Greeks painted sexual scenes on their ceramics, many of them famous for being some of the earliest depictions of same-sex relations and pederasty, and there are numerous sexually explicit paintings on the walls of ruined Roman buildings in Pompeii. The Moche of Peru in South America are another ancient people that sculpted explicit scenes of sex into their pottery.[2] There is an entire gallery devoted to pre-Columbian erotic ceramics (Moche culture) in Lima at the Larco Museum.

Additionally, there has been a long tradition of erotic painting in Eastern cultures. In Japan, for example, shunga appeared in the 13th century and continued to grow in popularity until the late 19th century when photography was invented.[3] Similarly, the erotic art of China reached its popular peak during the latter part of the Ming Dynasty.[4] In India, the famous Kama Sutra is an ancient sex manual that is still popularly read throughout the world.[5]

In Europe, starting with the Renaissance, there was a tradition of producing erotica for the amusement of the aristocracy. In the early 16th century, the text I Modi was an woodcut album created by the designer Giulio Romano, the engraver Marcantonio Raimondi and the poet Pietro Aretino. In 1601 Caravaggio painted the "Amor Vincit Omnia," for the collection of the Marquis Vincenzo Giustiniani.

An erotic cabinet, ordered by Catherine the Great, seems to have been adjacent to her suite of rooms in the Gatchina Palace. The furniture was highly eccentric with tables that had large penises for legs. Penises and vaginas were carved out on the furniture. The walls were covered in erotic art. There are photographs of this room and a Russian eye-witness has described the interior but the Russian authorities have always been very secretive about this peculiar Czarist heritage. The rooms and the furniture were seen in 1941 by two Wehrmacht-officers but they seem to have vanished since then.[6][7] A documentary by Peter Woditsch suggests that the cabinet was in the Peterhof Palace and not in Gatchina.[8]

The tradition was continued by other, more modern painters, such as Fragonard, Courbet, Millet, Balthus, Picasso, Edgar Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec, Egon Schiele, who served time in jail and had several works destroyed by the authorities for offending turn-of-the-century Austrian mores with his depictions of nude young girls.

By the 20th century, photography became the most interesting media for erotic art. Publishers like Taschen did a democratic display of erotic arts and erotic photography. Taschen books included Artist Hajime Sorayama, whom his peer artists call a cross between Norman Rockwell and Salvador Dalí or an imaginative modern day Vargas, is as close as one comes to modern Shunga. Sorayama's robotic works are in permanent collections of MoMA and the Smithsonian Institution as well as in the private WEAM Museum collections.

Modern

Today, erotic artists thrive, although in some circles, much of the genre is still not as well accepted as the more standard genres of art such as portraiture and landscape. During the last few centuries, society has broadened its view of what can be considered as art and several new styles developed during the 19th century such as Impressionism and Realism. This has given today's artists a broad variety of genres from which to choose, including; fantasy, pinup, horror, fetish, comics, anime, hentai, and many other niche genres all with erotic elements.

Classic "war-era" pin-ups like the works of Alberto Vargas, Gil Elvgren and Baron Von Lind, are still as popular as their contemporaries: Greg Hildebrandt, Olivia De Berardinis, Hajime Sorayama, Alain Aslan, Paul John Ballard, and others.

The acceptance and popularity of erotic art has pushed the genre into mainstream pop-culture and has created many famous icons. Frank Frazetta, Luis Royo, Boris Vallejo, Chris Achilleos, and Clyde Caldwell are among the artists whose work has been widely distributed.

The Guild of Erotic Artists were formed in 2002 to bring together a body of like minded individuals whose sole purpose was to express themselves and promote the sensual art of erotica for the modern age.

Legal standards

Whether or not an instance of erotic art is obscene depends on the standards of the community in which it is displayed.

In the United States, the 1973 ruling of the Supreme Court of the United States in Miller v. California established a three-tiered test to determine what was obscene—and thus not protected, versus what was merely erotic and thus protected by the First Amendment.

Delivering the opinion of the court, Chief Justice Warren Burger wrote,

The basic guidelines for the trier of fact must be: (a) whether 'the average person, applying contemporary community standards' would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest, (b) whether the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law; and (c) whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.[9]

As this is still, almost by necessity, much more vague than other judicial tests within U.S. jurisprudence, it has not reduced the conflicts that often result, especially from the ambiguities concerning what the "contemporary community standards" are. Similar difficulties in distinguishing between erotica and obscenity have been found in every legal system in the world.

Gallery

-

Oinochoe by the Shuvalov Painter, c. 430-420 BC

-

Erotic art by Peter Fendi

-

Erotic art by Peter Fendi

-

Hokusai, The Adonis Plant (Fukujusô), 1815.

-

Hokusai, The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife, c. 1820.

-

Gustave Courbet, L'Origine du monde, 1866.

-

Egon Schiele, untitled nude, 1914.

-

.jpg)

Erotic art by Édouard-Henri Avril.

-

.jpg)

Erotic art by Édouard-Henri Avril.

-

.jpg)

Erotic art by Édouard-Henri Avril.

-

.jpg)

Erotic art by Édouard-Henri Avril.

-

.jpg)

Erotic art by Édouard-Henri Avril.

-

_de_Pietro_Aretino%2C_5.jpg)

Erotic art by Paul Avril

-

Erotic art by Peter Johann Nepomuk Geiger

-

Sheela na Gig at Kilpeck, England.

-

Jupiter et Junon by Agostino Carracci (1557 - 1602).

-

Erotic sculpture at Khajuraho Temple walls.

See also

- Erotica

- Erotic Comix

- Erotic Fantasy Art

- Erotic Fetish Art

- Erotic Horror Art

- Erotic Pinup Art

- Hentai

- History of erotic photography

- History of erotic depictions

- I Modi

- Lesbianism in erotica

- Nudity in art

- Sex in advertising

- Sex in film

- Sexual arousal

References

- ↑ Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S. 184, 197 (1964).

- ↑ Chambers, M., Leslie, J. & Butts, S. (2005) Pornography: the Secret History of Civilization [DVD], Koch Vision.

- ↑ "Shunga". Japanese art net and architecture users system. 2001. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- ↑ Bertholet, L. C. P. (1997) "Dreams of Spring: Erotic Art in China," in: Bertholet Collection, Pepin Press (October, 1997) ISBN 90-5496-039-6.

- ↑ Daniélou, A., trans. (1993) The Complete Kama Sutra: the first unabridged modern translation, Inner Traditions. ISBN 0-89281-525-6

- ↑ Igorʹ Semenovich Kon and James Riordan, Sex and Russian Society page 18.

- ↑ http://www.trouw.nl/tr/nl/4512/Cultuur/archief/article/detail/1775415/2003/12/06/Het-Geheim-van-Catherina-de-Grote.dhtml Article in Trouw by Peter Dekkers. Retrieved 8 july 2014

- ↑ http://www.deproductie.nl/films/het-geheim-van-catherina-de-grote/ Trailer of the documentary by Peter Woditsch. Retrieved 8 july 2014

- ↑ Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15, 24 (1973).

External links

- "Seattle Erotic Art Festival" Seattle Erotic Art Festival, an annual exhibition in Seattle, Washington, USA

- "12 Inches of Sinl" 12 Inches of Sin, an annual international exhibition in Las Vegas, Nevada

- "Vintage Erotica Museum" Vintage Erotic Art, large unique collection with art and bio from many vintage illustrators

- "The Erotic Art Market" article from The World's Greatest Erotic Art, Vol.3

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||