Equirectangular projection

The equirectangular projection (also called the equidistant cylindrical projection, geographic projection, or la carte parallélogrammatique projection, and which includes the special case of the plate carrée projection or geographic projection) is a simple map projection attributed to Marinus of Tyre, who Ptolemy claims invented the projection about AD 100.[1] The projection maps meridians to vertical straight lines of constant spacing for meridional intervals of constant spacing, and circles of latitude to horizontal straight lines of constant spacing for constant intervals of parallels. The projection is neither equal area nor conformal. Because of the distortions introduced by this projection, it has little use in navigation or cadastral mapping and finds its main use in thematic mapping. In particular, the plate carrée has become a de facto standard for global raster datasets, such as Celestia and NASA World Wind, because of the particularly simple relationship between the position of an image pixel on the map and its corresponding geographic location on Earth.

Definition

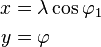

Given a spherical model,

where

is the longitude;

is the longitude; is the latitude;

is the latitude; are the standard parallels (north and south of the equator) where the scale of the projection is true;

are the standard parallels (north and south of the equator) where the scale of the projection is true; is the horizontal position along the map;

is the horizontal position along the map; is the vertical position along the map.

is the vertical position along the map.

The point (0,0) is at the center of the resulting projection.

The plate carrée (French, for square plate), is the special case where  is zero. This projection maps

is zero. This projection maps  to be the value of the longitude and

to be the value of the longitude and  to be the value of the latitude, and therefore is sometimes called the latitude/longitude or lat/lon(g) projection or is said (erroneously) to be “unprojected”.

to be the value of the latitude, and therefore is sometimes called the latitude/longitude or lat/lon(g) projection or is said (erroneously) to be “unprojected”.

While a projection with equally spaced parallels is possible for an ellipsoidal model, it would no longer be equidistant because the distance between parallels on an ellipsoid is not constant.

See also

- List of map projections

- Cartography

- Cassini projection

- Gall–Peters projection with resolution regarding the use of rectangular world maps

- Mercator projection

References

- ↑ Flattening the Earth: Two Thousand Years of Map Projections, John P. Snyder, 1993, pp. 5–8, ISBN 0-226-76747-7.

External links

- Global MODIS based satellite map The blue marble: land surface, ocean color and sea ice.

- Table of examples and properties of all common projections, from radicalcartography.net.

- Panoramic Equirectangular Projection, PanoTools wiki.