Equinox

| UT date and time of equinoxes and solstices on Earth[1] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| event | equinox | solstice | equinox | solstice | ||||

| month | March | June | September | December | ||||

| year | ||||||||

| day | time | day | time | day | time | day | time | |

| 2010 | 20 | 17:32 | 21 | 11:28 | 23 | 03:09 | 21 | 23:38 |

| 2011 | 20 | 23:21 | 21 | 17:16 | 23 | 09:04 | 22 | 05:30 |

| 2012 | 20 | 05:14 | 20 | 23:09 | 22 | 14:49 | 21 | 11:12 |

| 2013 | 20 | 11:02 | 21 | 05:04 | 22 | 20:44 | 21 | 17:11 |

| 2014 | 20 | 16:57 | 21 | 10:51 | 23 | 02:29 | 21 | 23:03 |

| 2015 | 20 | 22:45 | 21 | 16:38 | 23 | 08:20 | 22 | 04:48 |

| 2016 | 20 | 04:30 | 20 | 22:34 | 22 | 14:21 | 21 | 10:44 |

| 2017 | 20 | 10:28 | 21 | 04:24 | 22 | 20:02 | 21 | 16:28 |

| 2018 | 20 | 16:15 | 21 | 10:07 | 23 | 01:54 | 21 | 22:23 |

| 2019 | 20 | 21:58 | 21 | 15:54 | 23 | 07:50 | 22 | 04:19 |

| 2020 | 20 | 03:50 | 20 | 21:44 | 22 | 13:31 | 21 | 10:02 |

An equinox occurs twice a year, around 20 March and 22 September. The word itself has several related definitions. The oldest meaning is the day when daytime and night are of approximately equal duration.[2] The word equinox comes from this definition, derived from the Latin aequus (equal) and nox (night). The equinox is not exactly the same as the day when period of daytime and night are of equal length for two reasons. Firstly, sunrise, which begins daytime, occurs when the top of the Sun's disk rises above the eastern horizon. At that instant, the disk's center is still below the horizon. Secondly, Earth's atmosphere refracts sunlight. As a result, an observer sees daylight before the first glimpse of the Sun's disk above the horizon. To avoid this ambiguity, the word equilux is sometimes used to mean a day on which the periods of daylight and night are equal.[3][note 1] Times of sunset and sunrise vary with an observer's location (longitude and latitude), so the dates when day and night are closest together in length depend on location.

The other definitions are based on several related simultaneous astronomical events, and refer either to the events themselves or to the days on which they occur. These events are the reason that the period of daytime and night are approximately equal on the day of an equinox.

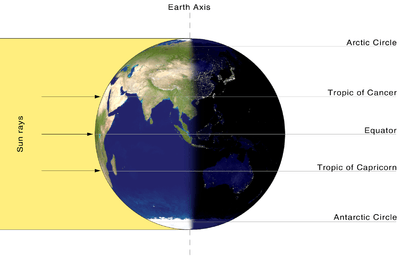

An equinox occurs when the plane of Earth's Equator passes the center of the Sun. At that instant, the tilt of Earth's axis neither inclines away from nor towards the Sun. The two annual equinoxes are the only times when the subsolar point—the place on Earth's surface where the center of the Sun is exactly overhead—is on the Equator, and, consequently, the Sun is at zenith over the Equator. The subsolar point crosses the equator, moving northward at the March equinox and southward at the September equinox.

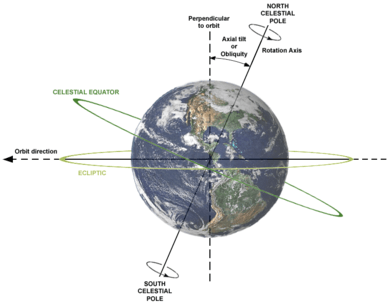

At an equinox, the Sun is at one of the two opposite points on the celestial sphere where the celestial equator (i.e. declination 0) and ecliptic intersect. These points of intersection are called equinoctial points: classically, the vernal point (RA = 00h 00m 00s and longitude = 0°) and the autumnal point (RA = 12h 00m 00s and longitude = 180°).

The equinoxes are the only times when the solar terminator is perpendicular to the Equator. As a result, the northern and southern Hemispheres are illuminated equally.

Equinoxes on the Earth

-

Diagram of the Earth's seasons as seen from the north. Far right: December solstice.

-

Diagram of the Earth's seasons as seen from the south. Far left: June solstice.

Date

When Julius Caesar established his calendar in 45 BC he set 25 March as the spring equinox. Because a Julian year (365.25 days) is slightly longer than the tropical year the calendar drifted with respect to the equinox, such that the equinox was occurring on about 21 March in AD 300 and by AD 1500 it had reached 11 March.

This drift induced Pope Gregory XIII to create a modern Gregorian calendar. The Pope wanted to continue to conform with the edicts concerning the date of Easter of the Council of Nicaea of AD 325, which means he wanted to move the vernal equinox to 21 March, which is the day allocated to it in the Easter table of the Julian calendar. However, the leap year intervals in his calendar were not smooth (400 is not an exact multiple of 97). This causes the equinox to oscillate by about 53 hours around its mean position. This in turn raised the possibility that it could fall on 22 March, and thus Easter Day might theoretically commence before the equinox. The astronomers chose the appropriate number of days to omit so that the equinox would swing from 19 to 21 March but never fall on the 22nd (although it can in a handful of years fall early in the morning of that day in the Far East)

The "mean position" is not the "mean vernal equinox" (defined as the moment when the Right Ascension of the Mean Sun (R.A.M.S.) is 0 hours). It changes constantly since the Gregorian calendar does not accurately track the tropical year. In 1903 the astronomical equinox fell at 7.15 PM on 21 March and in 2096 it will fall at 2.02 PM on 19 March, the median time being 26 1/2 hours from these extremes (all times GMT). In 1983 the mean equinox fell at 1.48 AM GMT on 23 March.

Names

- Vernal equinox and autumnal equinox: these classical names are direct derivatives of Latin (ver = spring and autumnus = autumn). These names are based on the seasons, and can be ambiguous since seasons of the northern hemisphere and southern hemisphere are opposites, and the vernal equinox of one hemisphere is the autumnal equinox of the other.

- March equinox and September equinox: names referring to the times of the year when such equinoxes occur. These usages are gaining popularity since they are without the ambiguity as to which hemisphere is the context, but are still only appropriate to cultures using the twelve months of the Gregorian calendar year or their linguistic counterparts.

- Spring equinox and fall equinox or autumn equinox: these are more colloquial names based on the seasons, and are also therefore ambiguous across hemispheres.

- Northward equinox and southward equinox: names referring to the apparent motion of the Sun at the times of the equinox. The least culturally biased terms.

- Vernal point and autumnal point are the points on the celestial sphere where the Sun is located on the vernal equinox and autumnal equinox respectively. Usually this terminology is fixed for the Northern hemisphere.

- First point (or cusp) of Aries and first point of Libra are names formerly used by astronomers and now used by navigators and astrologers. Navigational ephemeris tables record the geographic position of the First Point of Aries as the reference for position of navigational stars. Due to the precession of the equinoxes, the astrological signs of the tropical zodiac where these equinoxes are located no longer correspond with the actual constellations once ascribed to them. The equinoxes are currently in the constellations of Pisces and Virgo. In sidereal astrology (notably Hindu astrology), by contrast, the first point of Aries remains aligned with Ras Hammel "the head of the ram", i.e. the Aries constellation.

Length of equinoctial day and night

On the day of the equinox, the center of the Sun spends a roughly equal amount of time above and below the horizon at every location on the Earth, so night and day are about the same length. The word equinox derives from the Latin words aequus (equal) and nox (night). In reality, the day is longer than the night at an equinox. Day is usually defined as the period when sunlight reaches the ground in the absence of local obstacles. From the Earth, the Sun appears as a disc rather than a point of light, so when the center of the Sun is below the horizon, its upper edge is visible. Furthermore, the atmosphere refracts light, so even when the upper limb of the Sun is 0.4 degrees below the horizon, its rays curve over the horizon to the ground. In sunrise/sunset tables, the assumed semidiameter (apparent radius) of the Sun is 16 minutes of arc and the atmospheric refraction is assumed to be 34 minutes of arc. Their combination means that when the upper limb of Sun is on the visible horizon, its center is 50 minutes of arc below the geometric horizon, which is the intersection with the celestial sphere of a horizontal plane through the eye of the observer. These effects make the day about 14 minutes longer than the night at the Equator and longer still towards the poles. The real equality of day and night only happens in places far enough from the Equator to have a seasonal difference in day length of at least 7 minutes, actually occurring a few days towards the winter side of each equinox.

Because the Sun is a spherical (rather than a single-point) source of light, the actual crossing of the Sun over the Equator takes approximately 33 hours.

At the equinoxes, the rate of change for the length of daylight and night-time is the greatest. At the poles, the equinox marks the start of the transition from 24 hours of nighttime to 24 hours of daylight (or vice versa). Far north of the Arctic Circle, at Longyearbyen, Svalbard, Norway, there is an additional 15 minutes more daylight every day about the time of the Spring equinox, whereas in Singapore (which is just one degree of latitude north of the Equator), the amount of daylight in each daytime varies by just a few seconds.

Geocentric view of the astronomical seasons

In the half-year centered on the June solstice, the Sun rises north of east and sets north of west, which means longer days with shorter nights for the northern hemisphere and shorter days with longer nights for the southern hemisphere. In the half-year centered on the December solstice, the Sun rises south of east and sets south of west and the durations of day and night are reversed.

Also on the day of an equinox, the Sun rises everywhere on Earth (except at the poles) at about 06:00 and sets at about 18:00 (local time). These times are not exact for several reasons:

- The Sun is much larger in diameter than the Earth, so that more than half of the Earth could be in sunlight at any one time (due to unparallel rays creating tangent points beyond an equal-day-night line).

- Most places on Earth use a time zone which differs from the local solar time by minutes or even hours. For example, if the Sun rises at 07:00 on the equinox, it will set 12 hours later at 19:00.

- Even people whose time zone is equal to local solar time will not see sunrise and sunset at 06:00 and 18:00. This is due to the variable speed and the inclination of the Earth's orbit, and is described as the equation of time. It has different values for the March and September equinoxes (+8 and −8 minutes respectively).

- Sunrise and sunset are commonly defined for the upper limb of the solar disk, rather than its center. The upper limb is already up for at least a minute before the center appears, and the upper limb likewise sets later than the center of the solar disk. Also, when the Sun is near the horizon, atmospheric refraction shifts its apparent position above its true position by a little more than its own diameter. This makes sunrise more than two minutes earlier and sunset an equal amount later. These two effects combine to make the equinox day 12 h 7 min long and the night only 11 h 53 min. Note, however, that these numbers are only true for the tropics. For moderate latitudes, the discrepancy increases (e.g., 12 minutes in London); and closer to the poles it becomes very much larger (in terms of time). Up to about 100 km from either pole, the Sun is up for a full 24 hours on an equinox day.

- Night includes twilight. If dawn and dusk are instead considered daytime, the day would be almost 13 hours near the equator, and longer at higher latitudes.

- Height of the horizon changes the day's length. For an observer atop a mountain the day is longer, while standing in a valley will shorten the day.

Day arcs of the Sun

Some of the statements above can be made clearer by picturing the day arc (i.e., the path the Sun tracks along the celestial dome in its diurnal movement). The pictures show this for every hour on equinox day. In addition, some 'ghost' suns are also indicated below the horizon, up to 18° below it; the Sun in such areas still causes twilight. The depictions presented below can be used for both the northern hemisphere and the southern hemisphere. The observer is understood to be sitting near the tree on the island depicted in the middle of the ocean; the green arrows give cardinal directions.

- In the northern hemisphere, north is to the left, the Sun rises in the east (far arrow), culminates in the south (right arrow), while moving to the right and setting in the west (near arrow).

- In the southern hemisphere, south is to the left, the Sun rises in the east (near arrow), culminates in the north (right arrow), while moving to the left and setting in the west (far arrow).

The following special cases are depicted:

-

Day arc at 0° latitude (Equator)

The arc passes through the zenith, resulting in almost no shadows at high noon. -

Day arc at 20° latitude

The Sun culminates at 70° altitude and its path at sunrise and sunset occurs at a steep 70° angle to the horizon. Twilight still lasts about one hour. -

Day arc at 50° latitude

Twilight lasts almost two hours. -

Day arc at 70° latitude

The Sun culminates at no more than 20° altitude and its daily path at sunrise and sunset is at a shallow 20° angle to the horizon. Twilight lasts for more than four hours; in fact, there is barely any night. -

Day arc at 90° latitude (Pole)

If it were not for atmospheric refraction, the Sun would be on the horizon all the time.

Celestial coordinate systems

The vernal equinox occurs in March, about when the Sun crosses the celestial equator south to north. The term "vernal point" is used for the time of this occurrence and for the direction in space where the Sun is seen at that time, which is the origin of some celestial coordinate systems:

- in the ecliptic coordinate system, the vernal point is the origin of the ecliptic longitude;

- in the equatorial coordinate system, the vernal point is the origin of the right ascension.

Strictly speaking, at the equinox the Sun's ecliptic longitude is zero. Its latitude will not be exactly zero since the Earth is not exactly in the plane of the ecliptic. (The ecliptic is defined by the center of mass of the Earth and Moon combined.) The modern definition of equinox is the instants when the Sun's apparent longitude is 0° (northward equinox) or 180° (southward equinox).[4][5][6] This definition is used when astronomical almanacs are computed.

Because of the precession of the Earth's axis, the position of the vernal point on the celestial sphere changes over time, and the equatorial and the ecliptic coordinate systems change accordingly. Thus when specifying celestial coordinates for an object, one has to specify at what time the vernal point and the celestial equator are taken. That reference time is called the equinox of date.[7]

The autumnal equinox is at ecliptic longitude 180° and at right ascension 12h.

The upper culmination of the vernal point is considered the start of the sidereal day for the observer. The hour angle of the vernal point is, by definition, the observer's sidereal time.

The same is true in western tropical astrology: the vernal equinox is the first point (i.e. the start) of the sign of Aries. In this system, it is of no significance that the equinoxes shift over time with respect to the fixed stars.

Using the current official IAU constellation boundaries – and taking into account the variable precession speed and the rotation of the ecliptic – the equinoxes shift through the constellations as follows[8] (expressed in astronomical year numbering in which the year 0 = 1 BC, −1 = 2 BC, etc.):

- The March equinox passed from Taurus into Aries in year −1865, passed into Pisces in year −67, will pass into Aquarius in year 2597, will pass into Capricornus in year 4312. It passed along (but not into) a 'corner' of Cetus on 0°10' distance in year 1489.

- The September equinox passed from Libra into Virgo in year −729, will pass into Leo in year 2439.

Cultural aspects

A number of traditional spring and autumn (harvest) festivals are celebrated on the date of the equinoxes.

Equinoxes of other planets

Equinox is a phenomenon that can occur on any planet with a significant tilt to its rotational axis. Most dramatic of these is Saturn, where the equinox places its normally majestic ring system edge-on facing the Sun. As a result, they are visible only as a thin line when seen from Earth. When seen from above – a view seen by humans during an equinox for the first time from the Cassini space probe in 2009 – they receive very little sunshine, indeed more planetshine than light from the Sun.[9]

This lack of sunshine occurs once every 14.7 years. It can last a few weeks before and after the exact equinox. The most recent exact equinox for Saturn was on 11 August 2009. Its next equinox will take place on 30 April 2024.

One effect of equinoctial periods is the temporary disruption of communications satellites. For all geostationary satellites, there are a few days around the equinox when the sun goes directly behind the satellite relative to Earth (i.e. within the beam-width of the ground-station antenna) for a short period each day. The Sun's immense power and broad radiation spectrum overload the Earth station's reception circuits with noise and, depending on antenna size and other factors, temporarily disrupt or degrade the circuit. The duration of those effects varies but can range from a few minutes to an hour. (For a given frequency band, a larger antenna has a narrower beam-width and hence experiences shorter duration "Sun outage" windows.)

See also

- Aphelion – occurs around 5 July (see formula)

- Lady Day

- Nowruz

- Solstice

- Songkran (disambiguation)

- Sun outage – a phenomenon that occurs around the time of an equinox

Notes

- ↑ This meaning of "equilux" is rather modern (c. 2006) and unusual; technical references since the beginning of the 20th century (c. 1910) use the terms "equilux" and "isophot" to mean "of equal illumination", in the context of curves showing how intensely lighting equipment will illuminate a surface. See for instance John William Tudor Walsh, Textbook of Illuminating Engineering (Intermediate Grade), I. Pitman, 1947.

References

- ↑ United States Naval Observatory (2010-06-10). "Earth's Seasons: Equinoxes, Solstices, Perihelion, and Aphelion, 2000-2020".

- ↑ "equinox" at Oxford Dictionaries

- ↑ Owens, Steve (20 March 2010). "Equinox, Equilux, and Twilight Times". Dark Sky Diary (blog). Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ↑ Meeus, Jean (1997). Mathematical Astronomy Morsels.

- ↑ United States Naval Observatory (2006). Astronomical Almanac 2008. Glossary Chapter

- ↑ Meeus, Jean (1998). Astronomical Algorithms, Second Edition.

- ↑ Montenbruck, Oliver; Pfleger, Thomas. Astronomy on the Personal Computer. Springer-Verlag. p. 17. ISBN 0-387-57700-9.

- ↑ J. Meeus; Mathematical Astronomical Morsels; ISBN 0-943396-51-4

- ↑ "PIA11667: The Rite of Spring". Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Equinox |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Equinox. |

- Details about the Length of Day and Night at the Equinoxes. U.S. Naval Observatory. Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command

- Calculation of Length of Day (Formulas and Graphs)

- Equinoctial Points – The Nuttall Encyclopædia

- Table of times for Equinoxes, Solstices, Perihelion and Aphelion in 2000–2020

- Table of times of Spring Equinox for a thousand years: 1452–2547

- Gray, Meghan; Merrifield, Michael. "Solstice and Equinox". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||