Equatorial Rossby wave

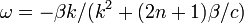

Equatorial Rossby waves, often called planetary waves, are very long, low frequency waves found near the equator and are derived using the equatorial Beta plane approximation,  , where "β" is the variation of the Coriolis parameter with latitude,

, where "β" is the variation of the Coriolis parameter with latitude,  . With this approximation, the primitive equations become the following:

. With this approximation, the primitive equations become the following:

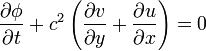

- the continuity equation (accounting for the effects of horizontal convergence and divergence and written with geopotential height):

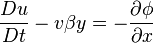

- the U-momentum equation (zonal wind component):

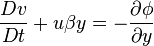

- the V-momentum equation (meridional wind component):

.[1]

.[1]

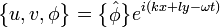

In order to fully linearize the primitive equations, one must assume the following solution:

.

.

Upon linearization, the primitive equations yield the following dispersion relation:

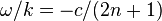

, where "c" is the phase speed of an equatorial Kelvin wave (

, where "c" is the phase speed of an equatorial Kelvin wave ( ).[2] Their frequencies are much lower than that of gravity waves and represent motion that occurs as a result of the undisturbed potential vorticity varying (not constant) with latitude on the curved surface of the earth. For very long waves (as the zonal wavenumber approaches zero), the non-dispersive phase speed is approximately:

).[2] Their frequencies are much lower than that of gravity waves and represent motion that occurs as a result of the undisturbed potential vorticity varying (not constant) with latitude on the curved surface of the earth. For very long waves (as the zonal wavenumber approaches zero), the non-dispersive phase speed is approximately:

, which indicates that these long equatorial Rossby waves move in the opposite direction (westward) of Kelvin waves (which move eastward) with speeds reduced by factors of 3, 5, 7, etc. To illustrate, suppose c = 2.8 m/s for the first baroclinic mode in the Pacific; then, the Rossby wave speed would correspond to approximately 0.9 m/s, requiring a 6-month time frame to cross the Pacific basin from east to west.[2] For very short waves (as the zonal wavenumber substantially increases), the group velocity (energy packet) is eastward and opposite to the phase speed, both of which are given by the following relations:

, which indicates that these long equatorial Rossby waves move in the opposite direction (westward) of Kelvin waves (which move eastward) with speeds reduced by factors of 3, 5, 7, etc. To illustrate, suppose c = 2.8 m/s for the first baroclinic mode in the Pacific; then, the Rossby wave speed would correspond to approximately 0.9 m/s, requiring a 6-month time frame to cross the Pacific basin from east to west.[2] For very short waves (as the zonal wavenumber substantially increases), the group velocity (energy packet) is eastward and opposite to the phase speed, both of which are given by the following relations:

- Frequency relation:

- Group velocity:

-

.[2]

.[2]

-

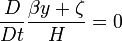

Thus, the phase and group speeds are equal in magnitude but opposite in direction (phase speed is westward and group velocity is eastward); note that is often useful to use potential vorticity as a tracer for these planetary waves, due to its invertability (especially in the quasi-geostrophic framework). Therefore, the physical mechanism responsible for the propagation of these equatorial Rossby waves is none other than the conservation of potential vorticity:

.[2]

.[2]

Thus, as a fluid parcel moves equatorward (βy approaches zero), the relative vorticity must increase and become more cyclonic in nature. Conversely, if the same fluid parcel moves poleward, (βy becomes larger), the relative vorticity must decrease and become more anticyclonic in nature.

As a side note, these equatorial Rossby waves can also be vertically-propagating waves when the Brunt–Vaisala frequency (buoyancy frequency) is held constant, ultimately resulting in solutions proportional to the following:

, where m is the vertical wavenumber and k is the zonal wavenumber.

, where m is the vertical wavenumber and k is the zonal wavenumber.

Equatorial Rossby waves can also adjust to equilibrium under gravity in the Tropics; because the planetary waves have frequencies much lower than gravity waves, the adjustment process tends to take place in two distinct stages. The first stage is rapid change due to the fast propagation of gravity waves (c = 300 m/s), the same as that on an f-plane (Coriolis parameter held constant), resulting in a flow that is close to being in geostrophic equilibrium. This stage could be thought of as the mass field adjusting to the wind field (due to the wavelengths being smaller than the Rossby deformation radius. The second stage is one where quasi-geostrophic adjustment takes place by means of planetary waves; this process can be comparable to the wind field adjusting to the mass field (due to the wavelengths being larger than the Rossby deformation radius.[1]