Equality of outcome

Equality of outcome, equality of condition, or equality of results is a political concept which is central to some political ideologies and is used regularly in political discourse, often in contrast to the term equality of opportunity.[2] It describes a state in which people have approximately the same material wealth or in which the general economic conditions of their lives are similar. Achieving equal results generally entails reducing or eliminating material inequalities between individuals or households in a society, and usually involves a transfer of income or wealth from wealthier to poorer individuals, or adopting other measures to promote equality of condition. A related way of defining equality of outcome is to think of it as "equality in the central and valuable things in life."[3] One account in the Journal of Political Philosophy suggested that the term meant "equalising where people end up rather than where or how they begin" but described this sense of the term as "simplistic" since it failed to identify what was supposed to be made equal.[4] There is widespread agreement that the term is controversial.

Comparisons with related concepts

Equality of outcome is often compared to related concepts of equality, particularly with equality of opportunity. Generally, most senses of the concept of equality are controversial, and are seen differently by people having different political perspectives, but of all of the terms relating to equality, equality of outcome is the most "controversial" or "contentious".[2]

- Equality of opportunity. This conception generally describes fair competition for important jobs and positions such that contenders have equal chances to win such positions,[5] and applicants are not judged or hampered by unfair or arbitrary discrimination.[6][7][8][9] It entails the "elimination of arbitrary discrimination in the process of selection."[10] The term is usually applied in workplace situations but has been applied in other areas as well such as housing, lending, and voting rights.[11] The essence is that job seekers have "an equal chance to compete within the framework of goals and the structure of rules established," according to one view.[12] It is generally seen as a procedural value of fair treatment by the rules.[13]

Equality of opportunity provides in a sense that all start the race of life at the same time. Equality of outcome attempts to ensure that everyone finishes at the same time.

—Mark Cooray, 1996[1]

- Equality of autonomy. This relatively new concept, a sort of hybrid notion, has been developed by philosopher Amartya Sen and can be thought of as "the ability and means to choose our life course should be spread as equally as possible across society."[14] It is an equal shot at empowerment or a chance to develop up to his or her potential rather than equal goods or equal chances. In a teaching guide, equality of autonomy was explained as "equality in the degree of empowerment people have to make decisions affecting their lives, how much choice and control they have given their circumstances."[3] Sen's approach requires "active intervention of institutions like the state into people's lives" but with an aim towards "fostering of people's self-creation rather than their living conditions."[15] Sen argued that "the ability to convert incomes into opportunities is affected by a multiplicity of individual and social differences that mean some people will need more than others to achieve the same range of capabilities."[16]

- Equality of process is related to the general notion of fair treatment, and can be thought of as "dealing with inequalities in treatment through discrimination by other individuals and groups, or by institutions and systems, including not being treated with dignity and respect," according to one definition.[17]

- Equality of perception. This is an uncommonly used term meaning that "person should be perceived as being of equal worth."[18]

Political philosophy

In political philosophy, there are differing views whether equal outcomes are beneficial or not. One view is that there is a moral basis for equality of outcome, but that means to achieve such an outcome can be malevolent. Equality of outcome can be a good thing after it has been achieved since it reflects the natural "interdependence of citizens in a highly organized economy" and provides a "basis for social policies" which foster harmony and good will, including social cohesion and reduced jealousy. One writer suggested greater socioeconomic equality was "indispensable if we want to realise our shared commonsense values of societal fairness."[19] Analyst Kenneth Cauthen in his 1987 book The Passion for Equality suggested that there were moral underpinnings for having equal outcomes because there is a common good––which people both contribute to and receive benefits from––and therefore should be enjoyed in common; Cauthen argued that this was a fundamental basis for both equality of opportunity as well as equality of outcome.[20] Analyst George Packer, writing in the journal Foreign Affairs, argued that "inequality undermines democracy" in the United States partially because it "hardens society into a class system, imprisoning people in the circumstances of their birth."[21] Packer elaborated that inequality "corrodes trust among fellow citizens" and compared it to an "odorless gas which pervades every corner" of the nation.[21]

An opposing view is that equality of outcomes is not beneficial overall for society since it dampens motivation necessary for humans to achieve great things, such as new inventions, intellectual discoveries, and artistic breakthroughs. According to this view, economic wealth and social status are rewards needed to spur such activity, and with these rewards diminished, then achievements which will ultimately benefit everybody will not happen as frequently.

If equality of outcomes is seen as beneficial for society, and if people have differing levels of material wealth and social prestige in the present, then methods to transform a society towards one with greater equality of outcomes is problematic. A mainstream view is that mechanisms to achieve equal outcomes––to take a society and with unequal socioeconomic levels and force it to equal outcomes––are fraught with moral as well as practical problems since they often involve political coercion to compel the transfer.[20]

And there is general agreement that outcomes matter. In one report in Britain, unequal outcomes in terms of personal wealth had a strong impact on average life expectancy, such that wealthier people tended to live seven years longer than poorer people, and that egalitarian nations tended to have fewer problems with societal issues such as mental illness, violence, teenage pregnancy, and other social problems.[22] Authors of the book The Spirit Level contended that "more equal societies almost always do better" on other measures, and as a result, striving for equal outcomes can have overall beneficial effects for everybody.[22]

Philosopher John Rawls, in his A Theory of Justice (1971), developed a "second principle of justice" that economic and social inequalities can only be justified if they benefit the most disadvantaged members of society. Further, Rawls claims that all economically and socially privileged positions must be open to all people equally. Rawls argues that the inequality between a doctor's salary and a grocery clerk's is only acceptable if this is the only way to encourage the training of sufficient numbers of doctors, preventing an unacceptable decline in the availability of medical care (which would therefore disadvantage everyone). Analyst Paul Krugman writing in The New York Times agreed with Rawls' position in which both equality of opportunity and equality of outcome were linked, and suggested that "we should try to create the society each of us would want if we didn’t know in advance who we’d be."[23] Krugman favored a society in which hard-working and talented people can get rewarded for their efforts but in which there was a "social safety net" created by taxes to help the less fortunate.[23]

Conflation with Marxism, socialism, and communism

The German economist and philosopher Karl Marx is sometimes mistakenly characterized as an egalitarian and a proponent of equality of outcome, and the economic systems of socialism and communism are sometimes misconstrued as being based on equality of outcome. In reality Marx eschewed the entire concept of equality as abstract and bourgeois in nature, focusing his analysis on more concrete issues such as opposition to exploitation based on economic and materialist logic. Marx eschewed theorizing on moral concepts and refrained from advocating principles of justice. Marx's views on equality were informed by his analysis of the development of the productive forces in society.[24][25]

Socialism is based on a principle of distribution whereby individuals receive compensation proportional to the amount of energy and labor they contribute to production ("To each according to his contribution"), which by definition precludes equal outcomes in income distribution.

In Marxist theory, communism is based on a principle whereby access to goods and services is based on need, stressing free access to the articles of consumption. The "equality" in a communist society is thus not about total equality or equality of outcome, but about equal and free access[26] to the articles of consumption. Marx argued that free access to consumption would enable individuals to overcome alienation.

However, socialists, communists and Marxists believe that by eliminating exploitation, their respective principle of compensation will lead to much greater equality than the capitalist inequality arising from private ownership of productive property that they oppose.

Comparing equalities: outcome vs opportunity

Both equality of outcome and equality of opportunity have been contrasted to a great extent. When evaluated in a simple context, the more preferred term in contemporary political discourse is equality of opportunity (or, meaning the same thing, the common variant "equal opportunities") which the public, as well as individual commentators, see as the nicer or more "well-mannered"[16] of the two terms.[27] And the term equality of outcome is seen as more controversial and is viewed skeptically. A mainstream political view is that the comparison of the two terms is valid, but that they are somewhat mutually exclusive in the sense that striving for either type of equality would require sacrificing the other to an extent, and that achieving equality of opportunity necessarily brings about "certain inequalities of outcome."[10][28] For example, striving for equal outcomes might require discriminating between groups to achieve these outcomes; or striving for equal opportunities in some types of treatment might lead to unequal results.[28] Policies that seek an equality of outcome often require a deviation from the strict application of concepts such as meritocracy, and legal notions of equality before the law for all citizens. 'Equality seeking' policies may also have a redistributive focus.

The two concepts, however, are not always cleanly contrasted, since the notion of equality is complex. Some analysts see the two concepts not as polar opposites but as highly related such that they can not be understood without considering the other term. One writer suggested it was unrealistic to think about equality of opportunity in isolation, without considering inequalities of income and wealth.[19] Another agreed that it is impossible to understand equality without some assessment of outcomes.[16] A third writer suggested that trying to pretend that the two concepts were "fundamentally different" was an error along the lines of a conceit.[22]

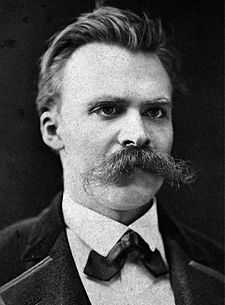

In contemporary political discourse, of the two concepts, equality of outcome has sometimes been criticized as the "politics of envy" and is often seen as more "controversial" than equality of opportunity.[16] One wrote that "equality of opportunity is then set up as the mild-mannered alternative to the craziness of outcome equality."[16] One theorist suggested that an over-emphasis on either type of equality can "come into conflict with individual freedom and merit."[20] The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche did not like either type of equality and was opposed in principle to democracy. He associated all equality with what he termed "slave morality."

Critics of equality of opportunity note that while it is relatively easier to deal with unfairness for people with different races or genders, it is much harder to deal with social class since "one can never entirely extract people from their ancestry and upbringing."[29] As a result, critics contend that efforts to bring fairness by equal opportunity are stymied by the difficulty of people having differing starting points at the beginning of the socio-economic competition. A person born into an upper-middle-class family will have greater advantages by the mere fact of birth than a person born into poverty.[29]

One newspaper account criticized discussion by politicians on the subject of equality as "weasely", and thought that the term was politically correct and vague. Furthermore, when comparing equality of opportunity with equality of outcome, the sense was that the latter type was "worse" for society.[30] Equality of outcome may be incorporated into a philosophy that ultimately seeks equality of opportunity. Moving towards a higher equality of outcome (albeit not perfectly equal) can lead to an environment more adept at providing equality of opportunity by eliminating conditions that restrict the possibility for members of society to fulfill their potential. For example, a child born in a poor, dangerous neighborhood with poor schools and little access to healthcare may be significantly disadvantaged in his attempts to maximize use of talents, no matter how fine his work ethic. Thus, even proponents of meritocracy may promote some level of equality of outcome in order to create a society capable of truly providing equality of opportunity.

While outcomes can usually be measured with a great degree of precision, it is much more difficult to measure the intangible nature of opportunities. That is one reason why many proponents of equal opportunity use measures of equality of outcome to judge success. Analyst Anne Phillips argued that the proper way to assess the effectiveness of the hard-to-measure concept of equality of opportunity is by the extent of the equality of outcome.[16] Nevertheless, she described a single criterion of equality of outcome as problematic: the measure of "preference satisfaction" was "ideologically loaded" while other measures such as income or wealth were inadequate, and she advocated an approach which combined data about resources, occupations, and roles.[16]

To the extent that inequalities can be passed from one generation to another through tangible gifts and wealth inheritance, some claim that equality of opportunity for children cannot be achieved without equality of outcome for parents. Moreover, access to social institutions is affected by equality of outcome and it's further claimed that rigging equality of outcome can be a way to prevent co-option of non-economic institutions important to social control and policy formation, such as the legal system, media or the electoral process, by powerful individuals or coalitions of wealthy people.

Purportedly, greater equality of outcome is likely to reduce relative poverty, leading to a more cohesive society. However, if taken to an extreme it may lead to greater absolute poverty if it negatively affects a country's GDP by damaging workers' sense of work ethic by destroying incentives to work harder. Critics of equality of outcome believe that it is more important to raise the standard of living of the poorest in absolute terms. Some critics additionally disagree with the concept of equality of outcome on philosophical grounds. Still others note that poor people of low social status often have a drive, hunger and ambition which ultimately lets them achieve better economic and social outcomes than their initially more advantaged rivals.

A related argument that is often encountered in education, especially in the debates on the grammar school in the United Kingdom and in the debates on gifted education in various countries, says that people by nature have differing levels of ability and initiative which result in some achieving better outcomes than others and it is therefore impossible to ensure equality of outcome without imposing inequality of opportunity.

The concept in political argument

The concept of equality of outcome is an important one in battling between differing political positions, since the concept of equality, overall, was seen as positive and an important foundation which is "deeply embedded in the fabric of modern politics."[10] There is much political jousting over what, exactly, equality means.[10] It is not a new phenomenon; battling between so-called haves and have-nots has happened throughout human civilization, and was a focus of philosophers such as Aristotle in his treatise Politics. Analyst Julian Glover in The Guardian wrote that equality challenged both left-leaning and right-leaning positions, and suggested that the task of left-leaning advocates is to "understand the impossibility and undesirability of equality" while the task for right-leaning advocates was to "realise that a divided and hierarchical society cannot – in the best sense of that word – be fair."[31]

- Conservatives. Analyst Glenn Oliver wrote that conservatives believed in neither equality of opportunity nor outcome.[32] In their view, life is not fair, but that is how it is. They criticize attempts to try to fight poverty by redistributive methods as ineffective since more serious cultural and behavioral problems lock poor people into poverty.[22] Sometimes right-leaning positions have been criticized by liberals for over-simplifying what is meant by the term equality of outcome,[19] and for construing outcomes strictly to mean precisely equal amounts for everybody. Commentator Ed Rooksby in The Guardian criticized the right's tendency to oversimplify, and suggested that serious left-leaning advocates would not construe equality to mean "absolute equality of everything".[10] Rooksby wrote that Marx favored the position described in the phrase "from each according to his ability, to each according to his need", and argued that this did not imply strict equality of things, but that it meant that people required "different things in different proportions in order to flourish."[10]

- Libertarians and advocates of economic liberalism such as Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman tend to see equality of outcome negatively and argue that any effort to cause equal outcomes would necessarily and unfortunately involve coercion by government. Friedman wrote that striving for equality of outcome leaves most people "without equality and without opportunity."[18]

- Liberals. Analyst Glenn Oliver suggested that liberals believed in "equality of opportunity and inequality of outcome."[32] One liberal position is that it is simplistic to define equality in strict outcomes since questions such as what is being equalized as well as huge differences in preferences and tastes and needs is considerable. They ask: exactly what is being equalized?[16] In the 1960s in the United States, mainstream liberal president Lyndon Johnson, examining the plight of African Americans locked in poverty, argued for ending policies which promoted segregation and discrimination as well as steps to end "economic injustice" by turning "equality of opportunity into equality of outcome,"[33] that is, with programs to transfer wealth in varying amounts. Fairness is emphasized; one writer expounding a centrist position wrote "people would neither be left to fend for themselves nor guaranteed equality of outcome - they would be given the tools they needed to achieve the American dream if they worked hard."[34] There has been cynicism expressed in the media that neither side, including mainstream political positions, wants to do anything substantive, but that the nebulous term fairness is used to cloak the inactivity because it is difficult to measure what, in fact, "fairness" means. Julian Glover wrote that fairness "compels no action" and compared it to an "atmospheric ideal, an invisible gas, a miasma," and to use an expression by Churchill, a "happy thought."[31]

- Social democrats champion greater equality of outcome and opportunities within capitalism, usually promoted through redistributive social policies like progressive taxation and the provision of universal public services.

- Socialists often believe in both "inequality of opportunity and equality of outcome" according to Oliver. They often see greater equality of outcome as a positive long-term goal to be achieved, so that individuals have equal access to the means of production and consumption. Only a small minority of socialist theories advocate complete economic equality of outcome (anarcho-communism is one such school). The vast majority of socialists view an ideal economy as one where remuneration is at least somewhat proportional to the degree of effort and personal sacrifice expended by individuals in the productive process. This latter concept was expressed by Karl Marx's famous maxim: To each according to his contribution.

See also

- Income inequality metrics

- Inequity aversion

- Equality under the law

- Ethnic Penalty

- Relative deprivation

- Harrison Bergeron

- Distributive justice

- Egalitarianism

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Dr. Mark Cooray, The Australian Achievement from Bondage to Freedom, 1996, Equality Of Opportunity And Equality Of Outcome, Accessed July 12, 2013

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Mark E. Rushefsky (2008). "Public Policy in the United States: At the Dawn of the Twenty-First Century". M. E. Sharpe Inc. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Equality Impact Assessments". Hull Teaching Primary Care. 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

Equality of autonomy - that is, equality in the degree of empowerment people have to make decisions affecting their lives, how much choice and control they have given their circumstances....

- ↑ Phillips, A. (2004). Defending equality of outcome, Journal of Political Philosophy, 12/1, 2004, pp. 1-19, Defending Equality of Outcome, Accessed July 12, 2013

- ↑ Nicole Richardt, Torrey Shanks (2008). "Equal Opportunity". International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. Retrieved 2011-09-12.

via Encyclopedia.com

- ↑ "equal opportunity". Collins English Dictionary. 2003. Retrieved 2011-09-12.

the offering of employment, pay, or promotion equally to all, without discrimination as to sex, race, colour, disability, etc.

- ↑ "equal opportunity". Princeton University. 2008. Retrieved 2011-09-12.

(thesaurus) equal opportunity - the right to equivalent opportunities for employment regardless of race or color or sex or national origin

- ↑ Carol Kitman (2011-09-12). "equal opportunity". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2011-09-12.

nondiscrimination in employment esp. as offered by an equal opportunity employer -- : a context in which there is no discrimination esp. with regard to sex, race, or social standing <alcoholism has become an equal opportunity disease — Carol Kitman>

- ↑ "equal opportunity". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (Houghton Mifflin). 2009. Retrieved 2011-09-12.

Absence of discrimination, as in the workplace, based on race, color, age, gender, national origin, religion, or mental or physical disability

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Ed Rooksby (14 October 2010). "The complexity of equality: Equality for the left is a complex concept, which bears little resemblance to the caricatures drawn by the right". The Guardian. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

... "equality of outcome" which, as every Telegraph journalist knows, is a Bad Thing and, anyway, "impossible". ...

- ↑ Paul de Vries (2011-09-12). "equal opportunity". Blackwell Reference. Retrieved 2011-09-12.

his standard has been used to define fairness in lending, housing, hiring, wage and salary levels, job promotion, voting rights ...

- ↑ John W. Gardner (1984). "Excellence: Can we be equal and excellent too?". Norton. ISBN 0-393-31287-9. Retrieved 2011-09-08.

(see page 47)...

- ↑ Mark E. Rushefsky (2008). "Public Policy in the United States: At the Dawn of the Twenty-First Century". M. E. Sharpe Inc. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

(page 36) ... A second meaning of equality is equality of opportunity, giving each person the right to develop to his or her potential....

- ↑ Sunder Katwala (21 October 2010). "It's equality of life chances, not literal equality, that the left espouses". The Guardian. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

... more equal life chances. Amartya Sen calls this equality of autonomy: that the ability and means to choose our life course should be spread as equally as possible across society. ...

- ↑ Todd May (2008). "The political thought of Jacques Rancière: creating equality". The Pennsylvania State University Press. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

(equality of autonomy) Amartya Sen ... aims that intervention at the fostering of people's self-creation rather than their living conditions. ...

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 16.7 Anne Phillips (2004). "Defending Equality of Outcome". Journal of Political Philosophy. pp. 1–19. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

- ↑ "Equality Impact Assessments". Hull Teaching Primary Care. 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

... Equality of process - dealing with inequalities in treatment through discrimination by other individuals and groups, or by institutions and systems, including not being treated with dignity and respect.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Equality, the goal not the signpost". Sociology. 27 April 2008. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

There are three forms of equality: equality of outcome, of opportunity, and of perception. Equality of perception is the most basic: it dictates that for people to be equal, each person should be perceived as being of equal worth. ...

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Martin O'Neill (12 October 2010). "Talk of fairness is hollow without material equality: Greater socioeconomic equality is indispensable if we want to realise our shared commonsense values of societal fairness". The Guardian. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Kenneth Cauthen (1987). "The Passion for Equality". Rowman & Littlefield. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

(page 136) There is a common good to which we contribute and from which we receive as members of a common system....

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 George Packer (November 2011). "The Broken Contract". Foreign Affairs.

Volume 90, Number 6 (see pages 29 and 31)

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Bagehot (Aug 19, 2010). "On equality: The lessons of the Spirit Level debate for the left, the right and the British public". The Economist. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

...“more equal societies almost always do better”. ...

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Paul Krugman (January 11, 2011). "More Thoughts on Equality of Opportunity". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

My vision of economic morality is more or less Rawlsian: we should try to create the society each of us would want if we didn’t know in advance who we’d be....

- ↑ Rejecting Egalitarianism, by Nielsen, Kai. 1987. Political Theory, Vol. 15, No. 3 (Aug., 1987), pp. 411-423.

- ↑ "Egalitarianism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 16 August 2002. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ↑ Steele, David Ramsay (September 1999). From Marx to Mises: Post Capitalist Society and the Challenge of Economic Calculation. Open Court. p. 66. ISBN 978-0875484495.

Marx distinguishes between two phases of marketless communism: an initial phase, with labor vouchers, and a higher phase, with free access.

- ↑ Lexington (Jul 7, 2011). "Fat cats and corporate jets: Why is it so unrewarding for politicians to bash the rich in America?". The Economist. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

The point here is only that Americans do not seem to mind about the widening inequality of income and wealth as much as you might expect them to in current circumstances. ...

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Edward Seidman, Julian Rappaport (editors) (1986). "Redefining social problems". Plenum Press. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

(page 292+) Conflict 3: Equal Opportunity versus Equality of Outcome ... By emphasizing on principle, the other conflicting one may have to be sacrificed.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Phillip Blond and John Milbank (27 January 2010). "No equality in opportunity: By synthesising old Tory and traditional left ideas a genuinely egalitarian society can be achieved". The Guardian. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

...Society and government can refuse race or gender prejudice simply by not being prejudicial. But class is not so easy: one can never entirely extract people from their ancestry and upbringing....

- ↑ Lucy Mangan (20 November 2010). "This week: Theresa May, Prince William and Kate Middleton and the Arnolds". The Guardian. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

"Equality", you see, is a weaselly, politically correct word that means either nothing or, worse, "equality of outcome". Imagine. From now on, we are going to have "fairness" and equality of opportunity. ...

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Julian Glover (10 October 2010). "The left should recognise that equality is undesirable: It sounds horribly rightwing, but a fair society may be one in which people have the right to strive for inequality". The Guardian. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

In the early days of New Labour it is said a media adviser whispered into an ambitious minister's ear after an interview: "We don't say equality, we say fairness." The former reeked of socialism – all taxes, empowerment schemes and regulation. The latter was as inoffensive as a scented candle. Everyone can agree to be fair – which is the problem.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Glenn Oliver. "What is the difference between Liberalism and Socialism ? I'd appreciate general rather than party political answers.". The Guardian. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

Conservatives believe in inequality of opportunity and inequality of outcome. Liberals believe in equality of opportunity and inequality of outcome. Socialists believe in inequality of opportunity and equality of outcome.

- ↑ Kevin Boyle (July 18, 2010). "James T. Patterson's "Freedom Is Not Enough," reviewed by Kevin Boyle". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

... Now it was time to address the economic injustice that kept almost half the black population below the poverty line, to turn equality of opportunity into equality of outcome....

- ↑ Mark Penn (January 31, 2011). "How Obama can find his center". Washington Post. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

The fundamental principle of centrism in the 1990s was that people would neither be left to fend for themselves nor guaranteed equality of outcome - they would be given the tools they needed to achieve the American dream if they worked hard....