Epiophlebia laidlawi

| Epiophlebia laidlawi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Naiad | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Odonata |

| Suborder: | Epiprocta |

| Infraorder: | Epiophlebioptera |

| Family: | Epiophlebiidae |

| Genus: | Epiophlebia |

| Species: | E. laidlawi |

| Binomial name | |

| Epiophlebia laidlawi Tillyard, 1921 | |

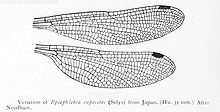

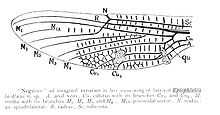

The Himalayan Relict Dragonfly (Epiophlebia laidlawi) is one of two species of Epiprocta in the family Epiophlebiidae. They are sometimes grouped as a suborder Anisozygoptera, considered as intermediate between the dragonflies and the damselflies, mainly because of the appearance the hind wings being very similar in size and shape to the forewings and held back over the body at rest as in the damselflies. This is now known to be in error however; in reality, the genus Epiophlebia shares a more recent ancestor with dragonflies and became separated from these in and around of the uplifting Himalayas.[1][2]

The species was first discovered from a larva collected in June 1918 by Stanley Kemp in a stream just above Sonada in the vicinity of Darjeeling. It was identified as an Epiophlebia by Dr. F. F. Laidlaw of Devon who dissected the wing sheaths of the specimen and his identification was endorsed by R.J. Tillyard, who described and gave it the commemorative name.[3]

This species was later found in several locations along the Himalayas including Chittrey, Mt. Shivapuri, Kathmandu area, Solokhumbu region, all in Nepal, where it breeds in streams between 6,000 and 11,500 ft (1,800–3,500m). The only other extant species in the genus, Epiophlebia superstes, is found in Japan. The two species have a similar physical appearance, black body with bright yellow stripes on the thorax and abdomen.[2]

E. laidlawi flies at 3000 to 3650 m and has few predators. Alan Davies suggested in 1992 that they bred in waterfalls at 2000 m with the adults flying higher later. Breeding sites at lower altitudes were discovered later. Peter Northcott mentioned 1860-2380m in 1988 but Stephen Butler discovered larvae on Shivapuri at 1800m.

The larvae grow for five to six years and is believed to be the longest recorded for any odonate. Specimens may emerge after nine years in many cases. Stephen Butler notes that the larvae stridulate when disturbed. The larvae appear like those of the anisoptera but are unable to use the anisopteran jet-propulsion mode of escape but walk.

The adult flight is slow and rather uncoordinated. The discoidal cell in the forewing is uncrossed and foursided and the hindwing the crossvein is long making the cell distally wide. The arculus is situated between the primary antenodals. The male grasps the female behind the head as in the anisoptera. The female is not accompanied during egg laying. She lays eggs into plant tissue while sitting on the stem of a waterside plant. The eggs are laid from bottom to top in a regular zig-zag pattern. The preferred plants are usually bryophytes.[4]

Cited references

- ↑ Tillyard R J (1921). "On an Anisozygopterous Larva from the Himalayas (Order Odonata)". Records of the Indian Museum 22 (2): 93–107.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Fraser FC (1934). Fauna of British India. Odonata. Volume 2. Taylor & Francis. p. 151.

- ↑ Fraser, F.C. (1935). "A missing link". The Journal of the Darjeeling Natural History Society 10 (2): 56–59.

- ↑ Silby, Jill (2001) Dragonflies of the world. The Natural History Museum. London.

References

- Butler, Stephen G. 1997. Notes on the collection and transportation of live Epiophlebia laidlawi Tillyard larvae (Anisozygoptera: Epiophlebiidae). Notul. odonatol. 4(9): 147–148.

- Sharma, S. and Ofenböck, T. 1996. New discoveries of Epiophlebia laidlawi Tillyard, 1921 in the Nepal Himalaya (Odonata, Anisozygoptera: Epiophlebiidae). Opusc. zool. flumin. 150: 1–11

- Svihla, A. 1962. Records of the larvae of Epiophlebia laidlawi Tillyard from the Darjeeling area (Odonata: Anisozygoptera). Ent. News lxxiii: 5–7.

- Svihla, A. 1964. Another record of the larva of Epiophlebia laidlawi Tillyard (Odonata: Anisozygoptera). Ent. News lxxii: 66–67.

- Tani, K. and Miyatake, Y. 1979. The discovery of Epiophlebia laidlawi Tillyard, 1921 in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal (Anisozygoptera: Epiophlebiidae). Odonatologica 8(4): 329–332

External links

- Clausnitzer, V. (2008). Epiphlebia laidlawi. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 8 October 2009.