Energy transition in Germany

Energiewende (German for Energy transition) is the transition by Germany to an energy portfolio dominated by renewable energy, energy efficiency and sustainable development. The final goal is the abolition of coal and other non-renewable energy sources.[2]

Renewable energy encompasses wind, biomass (such as landfill gas and sewage gas), hydropower, solar power (thermal and photovoltaic), geothermal, and ocean power. These renewable sources are to serve as an alternative to fossil fuels (oil, coal, natural gas) and nuclear fuel (uranium).

Piecemeal measures often have only limited potential, so a timely implementation for this transition requires multiple approaches in parallel. Energy conservation and improvements in energy efficiency thus play a major role. An example of an effective energy conservation measure is improved insulation for buildings; an example of improved energy efficiency is cogeneration of heat and power. Smart electric meters can schedule energy consumption for times when electricity is available inexpensively.

The term

This term was the title of a 1980 publication by the German Öko-Institut, calling for the complete abandonment of nuclear and petroleum energy.[3] On the February 16 of that year the German Federal Ministry of the Environment also hosted a symposium in Berlin, called Energiewende – Atomausstieg und Klimaschutz (Energy Transition: Nuclear Phase-Out and Climate Protection). The views of the Öko-Institut, initially strongly opposed, have gradually become common knowledge in energy policy. In the following decades the term expanded in scope; in its present form it dates back to at least 2002.

Energiewende designates a significant change in energy policy: The term encompasses a reorientation of policy from demand to supply and a shift from centralized to distributed generation (for example, producing heat and power in very small cogeneration units), which should replace overproduction and avoidable energy consumption with energy-saving measures and increased efficiency.

In a broader sense this transition also entails a democratization of energy:[4] In the traditional energy industry, a few large companies with large centralized power stations dominate the market as an oligopoly and consequently amass a worrisome level of both economic and political power. Renewable energies, in contrast, can as a rule be established in a decentralized manner. Public wind farms and solar parks can involve many citizens directly in energy production.[5] Photovoltaic systems can even be set up by individuals. Municipal utilities can also benefit citizens financially, while the conventional energy industry profits a relatively small number of shareholders. Also significant, the decentralized structure of renewable energies enables creation of value locally and minimizes capital outflows from a region. Renewable energy sources therefore play an increasingly important role in municipal energy policy, and local governments often promote them.

Status

The key policy document outlining the Energiewende was published by the German government in September 2010, some six months before the Fukushima nuclear accident.[6] Legislative support was passed in 2011. Important aspects include:

- greenhouse gas reductions: 80–95% reduction by 2050

- renewable energy targets: 60% share by 2050 (renewables broadly defined as hydro, solar and wind power)

- energy efficiency: electricity efficiency up by 50% by 2050

- an associated research and development drive

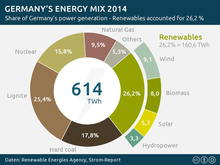

The policy has been embraced by the German federal government and has resulted in a huge expansion of renewables, particularly wind power. Germany's share of renewables has increased from around 5% in 1999 to 22.9% in 2012, surpassing the OECD average of 18% usage of renewables.[7] Producers have been guaranteed a fixed feed-in tariff for 20 years, guaranteeing a fixed income. Energy co-operatives have been created, and efforts were made to decentralize control and profits. The large energy companies have a disproportionately small share of the renewables market. However, in some cases poor investment designs have caused bankruptcies and low returns, and unrealistic promises have been shown to be far from reality.[8] Nuclear power plants were closed, and the existing 9 plants will close earlier than planned, in 2022.

One factor that has inhibited efficient employment of new renewable energy has been the lack of an accompanying investment in power infrastructure to bring the power to market. It is believed 8,300 km of power lines must be built or upgraded.[7] The different German States have varying attitudes to the construction of new power lines. A second factor is the storage capacity needed to create a stable electricity supply from wind and solar energy is far beyond what can be realized in Germany. A third factor is the amount of windmills needed to meet the German electricity consumption can by far not be realized on German territory.[9] Industry has had their rates frozen and so the increased costs of the Energiewende have been passed on to consumers, who have had rising electricity bills. Germans in 2013 had some of the highest electricity costs in Europe.[10] In comparison, their nuclear-reliant neighbour France has some of the cheapest in the EU (#7 out of 27).

According to a 2014 survey conducted by TNS Emnid for the German Renewable Energies Agency [12] among 1015 respondents, 94 per cent of the Germans support the enforced expansion of Renewable Energies. More than two-thirds of the interviewees agrees to renewable power plants close to their homes.

Criticisms

The Energiewende has not been without its critics. The weekly German magazine Der Spiegel has described it as "massively expensive" and that it has "done nothing to make the environment cleaner or encourage genuine efficiency."[13] German bureaucrats have come up with over 4,000 different subsidy categories for renewable energy. Der Spiegel describes the Energiewende as "an environment killer which burdens the climate, accelerates the greenhouse effect and causes irreversible damage.[13][14] German Economy and Energy Minister Sigmar Gabriel admitted "For a country like Germany with a strong industrial base, exiting nuclear and coal-fired power generation at the same time would not be possible."[15][16] Germany's CO2 emissions were escalating in 2012 and 2013 and it is planned to reopen some of the dirtiest brown coalmines that had previously been closed.[17][18] Nonetheless, in 2014 carbon emissions had declined again. More renewable energy had been generated and a greater energy efficiency had been achieved.[19]

Reception by other countries

United States

In his article [20] Robert Fares states two lessons to be learned from the German example:

- Coherent government policy can transform an industry

- It is possible to blend low-risk feed-in tariffs with market price signals

See also

- Energy transition

- Renewable energy in the European Union

- Passivhaus

- Renewable energy commercialization

- List of countries by renewable electricity production

- Germany National Renewable Energy Action Plan

- Berlin Declaration (2007)

- Wildpoldsried

- German Solar Industry Association

- Amory Lovins

- Soft energy path

- The Fourth Revolution: Energy

- 100% renewable energy

References

- ↑ Germany's Electricity Mix 2014

- ↑ Federal Ministry for the Environment (29 March 2012). Langfristszenarien und Strategien für den Ausbau der erneuerbaren Energien in Deutschland bei Berücksichtigung der Entwicklung in Europa und global [Long-term Scenarios and Strategies for the Development of Renewable Energy in Germany Considering Development in Europe and Globally]. Berlin, Germany: Federal Ministry for the Environment (BMU).

- ↑ Krause, Bossel, Müller-Reißmann: Energiewende – Wachstum und Wohlstand ohne Erdöl und Uran, S. Fischer Verlag 1980, ASIN: B0029KUZBI. (Energy Transition – Growth and Prosperity without Petroleum and Uranium)

- ↑ Henrik Paulitz: Dezentrale Energiegewinnung - Eine Revolutionierung der gesellschaftlichen Verhältnisse. IPPNW. (Decentralized Energy Production - Revolutionizing Social Relations) Accessed 20 January 2012.

- ↑ Mit Bürgerengagement zur Energiewende. (With Citizen Involvement for the Energy Transition) Website of the organization Deutscher Naturschutzring. Cited as of 17 February 2012.

- ↑ Bundesregierung Deutschland (28 September 2010). Energiekonzept für eine umweltschonende, zuverlässige und bezahlbare Energieversorgung [Energy Concept for an Environmentally-Friendly, Reliable, and Affordable Energy Supply]. Berlin, Deutschland: Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Technologie (BMWi) und Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und Reaktorsicherheit (BMU) (Federal Ministry for Economy and Technology, and Federal Ministry for Environment, Conservation, and Reactor Safety).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Germany’s energy transformation Energiewende". The Economist. Jul 28, 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ Gunther Latsch, Anne Seith and Gerald Traufetter. "Gone With the Wind: Weak Returns Cripple German Renewables" Der Spiegel, 30 January 2014. Accessed: 5 January 2015.

- ↑ ″Energiewende ins nichts″, video of presentation by professor Hans Werner Sinn on December 16, 2013

- ↑ "Germany’s energy reform Troubled turn". The Economist. 9 Feb 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ A power plant in your neighborhood?

- ↑ Acceptance of Renewable Energies 2014

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Germany's Defective Green Energy Game Plan".

- ↑ "Germany's Energy Poverty: How Electricity Became a Luxury Good".

- ↑ Thorsten Severin and Victoria Bryan (October 12, 2014). "Germany says can't exit coal-fired energy at same time as nuclear". reuters.

- ↑ Sigmar Gabriel (October 13, 2014). http://www.altinget.se/misc/SigmarGabriel.pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Graham Lloyd (Jan 11, 2014). "Europe and renewables lose their attraction".

- ↑ Tino Andresen (April 15, 2014). "Coal Returns to German Utilities Replacing Lost Nuclear". Bloomberg.

- ↑ Energiewende verringert CO2-Emissionen. Deutsche Welle, retrieved 13.2.2015.

- ↑ Robert Fares (2014-10-07). "Energiewende: Two Energy Lessons for the United States from Germany". Scientific American blog. Retrieved 2014-12-03.

External links

- German Energy Transition

- Energy Concept for an Environmentally Sound, Reliable and Affordable Energy Supply (an English translation of the German policy document)