Energy transition

Energy transition means a long-term structural change in energy systems.[1] These have occurred in the past, and still occur worldwide. Historic energy transitions are most broadly described by Vaclav Smil.[2] Contemporary energy transitions differ in terms of motivation and objectives, drivers and governance. In a more narrow sense, a sustainable energy transition is the shift by some countries, most notably Germany (German: Energiewende), to decentralised renewable energy, and energy efficiency. Although so far these shifts have been replacing nuclear energy, their declared goal is also the abolishment of coal and other non-renewable energy sources[3] and the creation of an energy system based on 100% renewable energy.

Renewable energy encompasses wind, biomass (such as landfill gas and sewage gas), hydropower, solar power (thermal and photovoltaic), geothermal, and ocean power. These renewable sources are to serve as an alternative to fossil fuels (oil, coal, natural gas) and nuclear fuel (uranium). Solving the energy problem is regarded as the most important challenge humankind has to face in the 21st century.[4]

Piecemeal measures often have only limited potential, so a timely implementation for the energy transition requires multiple approaches in parallel. Energy conservation and improvements in energy efficiency thus play a major role. An example of an effective energy conservation measure is improved insulation for buildings; an example of improved energy efficiency is cogeneration of heat and power. Smart electric meters can schedule energy consumption for times when electricity is available inexpensively.

After such a transitional period, with a continuing increase in renewable energy production these are expected to make up most, if not all, of the world's energy production in 50 years according to a 2011 projection by the International Energy Agency, dramatically reducing the emissions of greenhouse gases.[5]

The Term

This term was the title of a 1980 publication by the German Öko-Institut, calling for the complete abandonment of nuclear and petroleum energy.[6] On the 16th of February of that year the German Federal Ministry of the Environment also hosted a symposium in Berlin, called Energy Transition: Nuclear Phase-Out and Climate Protection. The views of the Öko-Institut, initially so strongly opposed, have gradually become common knowledge in energy policy. In the following decades the term expanded in scope; in its present form it dates back to at least 2002.

'Energy transition' designates a significant change in energy policy: The term encompasses a reorientation of policy from demand to supply and a shift from centralized to distributed generation (for example, producing heat and power in very small cogeneration units), which should replace overproduction and avoidable energy consumption with energy-saving measures and increased efficiency.

In a broader sense the energy transition also entails a democratization of energy:[7] In the traditional energy industry, a few large companies with large centralized power stations dominate the market as an oligopoly and consequently amass a worrisome level of both economic and political power. Renewable energies, in contrast, can as a rule be established in a decentralized manner. Public wind farms and solar parks can involve many citizens directly in energy production.[8] Photovoltaic systems can even be set up by individuals. Municipal utilities can also benefit citizens financially, while the conventional energy industry profits a relatively small number of shareholders. Also significant, the decentralized structure of renewable energies enables creation of value locally and minimizes capital outflows from a region. Renewable energy sources therefore play an increasingly important role in municipal energy policy, and local governments often promote them.

Status in Specific Countries

Austria

Austria embarked on its Energy Transition (the Energiewende) some decades ago. Due to geographical conditions, energy production in Austria relies heavily on renewable energies, notably hydropower. 78,4% of domestic production in 2013 came from renewable energy, 9,2% from natural gas and 7,2% from petroleum. (rest: waste). On the basis of the Federal Constitutional Law for a Nuclear-Free Austria, no nuclear power plants are in operation in Austria.

But domestic energy production makes up only 36% of Austria's total energy consumption, which among other things encompasses transport, electricity production, and heating. In 2013 Oil accounts for about 36,2% of total energy consumption, renewable energies 29,8%, gas 20,6%, and coal 9,7%. In the past 20 years, the structure of gross domestic energy consumption has shifted from coal and oil to new renewables, in particular between 2005 to 2013 (plus 60%). The EU target for Austria require a renewables share of 34% by 2020 (gross final energy consumption). Austria is on a good way to achieve this target (32,5% in 2013). Energy transition in Austria can be also seen on the local level, in some villages, towns and regions. For example, the town of Güssing in the state of Burgenland is a pioneer in independent and sustainable energy production. Since 2005, Güssing has already produced significantly more heating (58 gigawatt hours) and electricity (14 GWh) from renewable resources than the city itself needs.[11] [9]

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom is mainly focusing on wind power, both onshore and offshore, and in particular is strongly promoting the establishment of offshore wind power. With an installed capacity of 2.1 GW (about half of the world's installed offshore wind power), Britain is the worldwide leader. At the end of 2012, the country had an 8.4 GW of overall installed wind power capacity, putting it in fourth place worldwide, after China, the United States, and Germany. It was initially promoted with a quota system, but expansion targets were missed repeatedly. This led the government to implement a feed-in tariff instead.[10]

Denmark

Denmark, as a country reliant on imported oil, was impacted particularly hard by the 1973 oil crisis. This roused public discussions on building nuclear power plants to diversify energy supply. A strong anti-nuclear movement developed, which fiercely criticized nuclear power plans taken up by the government,[11] and this ultimately led to a 1985 resolution not to build any nuclear power plants in Denmark.[12] The country instead opted for renewable energy, focusing primarily on wind power. Wind turbines for power generation already had a long history in Denmark, as far back as the late 1800s. As early as 1974 a panel of experts declared "that it should be possible to satisfy 10% of Danish electricity demand with wind power, without causing special technical problems for the public grid."[13] Denmark undertook the development of large wind power stations — though at first with little success (like with the Growian project in Germany).

Small facilities prevailed instead, often sold to private owners such as farms. Government policies promoted their construction; at the same time, positive geographical factors favored their spread, such as good wind power density and Denmark's decentralized patterns of settlement. A lack of administrative obstacles also played a role. Small and robust systems came on line, at first in the power range of only 50-60 kilowatts — using 1940s technology and sometimes hand-crafted by very small businesses. In the late seventies and the eighties a brisk export trade to the United States developed, where wind energy also experienced an early boom. In 1986 Denmark already had about 1200 wind power turbines,[14] though they still accounted for just barely 1% of Denmark's electricity.[15] This share increased significantly over time. In 2011, renewable energies covered 41% of electricity consumption, and wind power facilities alone accounted for 28%.[16] The government aims to increase wind energy's share of power generation to 50% by 2020, while at the same time reducing carbon dioxide emissions by 40%.[17] On 22 March 2012, the Danish Ministry of Climate, Energy and Building published a four-page paper titled "DK Energy Agreement," outlining long-term principles for Danish energy policy.[18]

The installation of oil and gas heating is banned in newly constructed buildings from the start of 2013; beginning in 2016 this will also apply to existing buildings. At the same time an assistance program for heater replacement was launched. Denmark's goal is to reduce the use of fossil fuels 33% by 2020. The country is scheduled to attain complete independence from petroleum and natural gas by 2050.[19]

France

Since 2012, political discussions have been developing in France about the energy transition and how the French economy might profit from it.[20]

In September 2012, Minister of the Environment Delphine Batho coined the term "ecological patriotism." The government began a work plan to consider starting the energy transition in France. This plan should address the following questions by June 2013:[21]

- How can France move towards energy efficiency and energy conservation? Reflections on altered lifestyles, changes in production, consumption, and transport.

- How to achieve the energy mix targeted for 2025? France's climate protection targets call for reducing greenhouse gas emissions 40% by 2030, and 60% by 2040.

- Which renewable energies should France rely on? How should the use of wind and solar energy can be promoted?

- What costs and funding models will likely be required for alternative energy consulting and investment support? And how about for research, renovation, and expansion of district heating, biomass, and geothermal energy? One solution could be a continuation of the CSPE, a tax that is charged on electricity bills.

The Environmental Conference on Sustainable Development on 14 and 15 September 2012 treated the issue of the environmental and energy transition as its main theme.[22]

On 8 July 2013, the national debate leaders submits some proposals to the government. Among them, there were environmental taxation, and smart grid development.[23]

Germany

The key policy document outlining the Energiewende was published by the German government in September 2010, some six months before the Fukushima nuclear accident.[24] Legislative support was passed in 2011. Important aspects include:

- greenhouse gas reductions: 80–95% reduction by 2050

- renewable energy targets: 60% share by 2050 (renewables broadly defined as hydro, solar and wind power)

- energy efficiency: electricity efficiency up by 50% by 2050

- an associated research and development drive

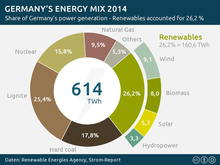

The policy has been embraced by the German federal government and has resulted in a huge expansion of renewables, particularly wind power. Germanys share of renewables has increased from around 5% in 1999 to 17% in 2010, reaching close to the OECD average of 18% usage of renewables.[26] Producers have been guaranteed a fixed feed-in tariff for 20 years, guaranteeing a fixed income. Energy co-operatives have been created, and efforts were made to decentralize control and profits. The large energy companies have a disproportionately small share of the renewables market. Nuclear power plants were closed, and the existing 9 plants will close earlier than necessary, in 2022.

The reduction of reliance on nuclear plants has had the consequence of increased reliance on fossil fuels. One factor that has inhibited efficient employment of new renewable energy has been the lack of an accompanying investment in power infrastructure to bring the power to market. It is believed 8 300 km of power lines must be built or upgraded.[26]

Different Länder have varying attitudes to the construction of new power lines. Industry has had their rates frozen and so the increased costs of the Energiewende have been passed on to consumers, who have had rising electricity bills. Germans in 2013 had some of the highest electricity costs in Europe.[27]

Japan

On 14 September 2012 the Japanese government decided at a ministerial meeting in Tokyo to phase out nuclear power by the 2030s, or 2040 at the very latest. The government said that it would take "all possible measures" to achieve this goal.[28] A few days later the government retrenched the planned nuclear phaseout after the industry pushed for reconsideration. Arguments cited were that a nuclear phaseout would burden the economy, and that imports of oil, coal, and gas would bring high added costs. The government then approved the energy transition, but left open the time-frame for decommissioning the nuclear power plants.[29]

See also

- Renewable energy in the European Union

- Energy Transition in Germany

- Passivhaus

- Renewable energy commercialization

- List of countries by renewable electricity production

- Germany National Renewable Energy Action Plan

- Berlin Declaration (2007)

- Wildpoldsried

- German Solar Industry Association

- Amory Lovins

- Soft energy path

- The Fourth Revolution: Energy

- 100% renewable energy

References

- ↑ World Energy Council. 2014. Global Energy Transitions.

- ↑ Smil, Vaclav. 2010. Energy Transitions. History, Requirements, Prospects. Praeger

- ↑ Federal Ministry for the Environment (29 March 2012). Langfristszenarien und Strategien für den Ausbau der erneuerbaren Energien in Deutschland bei Berücksichtigung der Entwicklung in Europa und global [Long-term Scenarios and Strategies for the Development of Renewable Energy in Germany Considering Development in Europe and Globally] (PDF). Berlin, Germany: Federal Ministry for the Environment (BMU).

- ↑ Nicola Armaroli, Vincenzo Balzani, The Future of Energy Supply: Challenges and Opportunities. In: Angewandte Chemie 46, (2007), 52-66, p. 52, doi:10.1002/anie.200602373.

- ↑ Ben Sills (Aug 29, 2011). "Solar May Produce Most of World’s Power by 2060, IEA Says". Bloomberg.

- ↑ Krause, Bossel, Müller-Reißmann: Energiewende – Wachstum und Wohlstand ohne Erdöl und Uran, S. Fischer Verlag 1980, ASIN: B0029KUZBI. (Energy Transition – Growth and Prosperity without Petroleum and Uranium)

- ↑ Henrik Paulitz: Dezentrale Energiegewinnung - Eine Revolutionierung der gesellschaftlichen Verhältnisse. IPPNW. (Decentralized Energy Production - Revolutionizing Social Relations) Accessed 20 January 2012.

- ↑ Mit Bürgerengagement zur Energiewende. (With Citizen Involvement for the Energy Transition) Website of the organization Deutscher Naturschutzring. Cited as of 17 February 2012.

- ↑ Modell Güssing - Wussten Sie, dass ....

- ↑ Erneuerbare Energien: Quotenmodell keine Alternative zum EEG. DIW Wochenbericht 45/2012, S.18f. accessed on 14 April 2013.

- ↑ Sonne: Im Norden ging die auf. In Tagesspiegel, 18 October 2010. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ↑ Nuclear Energy in Denmark. http://www.world-nuclear.org. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ↑ Erich Hau, Windkraftanlagen: Grundlagen, Technik, Einsatz, Wirtschaftlichkeit, Berlin - Heidelberg 2008, p45.

- ↑ Die Kraft aus der Luft. In: Die Zeit, 6 February 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ↑ Erich Hau, Windkraftanlagen: Grundlagen, Technik, Einsatz, Wirtschaftlichkeit, Berlin - Heidelberg 2008, p56.

- ↑ Renewables now cover more than 40% of electricity consumption. Danish Energy Agency. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ↑ Dänemark hat neue Regierung In: Neues Deutschland, 4 October 2011. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ↑ DK Energy Agreement. March 22, 2012.

- ↑ Abschied vom Ölkessel. In: heise.de, 16 February 2013. accessed on 16 February 2013.

- ↑ La transition énergétique, un vrai vecteur de croissance pour la France Les échos, Mai 2012

- ↑ Transition énergétique: quels moyens et quels coûts? batiactu 21. September 2012

- ↑ Conférence environnementale des 14-15 septembre 2012 developpement-durable.gouv.fr, September 2012

- ↑ http://www.transition-energetique.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/dnte_synthese_nationale_des_debats_territoriaux.pdf

- ↑ Bundesregierung Deutschland (28 September 2010). Energiekonzept für eine umweltschonende, zuverlässige und bezahlbare Energieversorgung [Energy Concept for an Environmentally-Friendly, Reliable, and Affordable Energy Supply] (PDF). Berlin, Deutschland: Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Technologie (BMWi) und Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und Reaktorsicherheit (BMU) (Federal Ministry for Economy and Technology, and Federal Ministry for Environment, Conservation, and Reactor Safety).

- ↑ Germany's Electricity Mix 2014

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Germany’s energy transformation Energiewende". The Economist. Jul 28, 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ "Germany’s energy reform Troubled turn". The Economist. 9 Feb 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ Wegen Reaktorunglück in Fukushima: Japan verkündet Atomausstieg bis 2040 at focus.de, 14 September 2012 (accessed on 14 September 2012).

- ↑ Energiewende: Japan schränkt Atomausstieg wieder ein at zeit.de, 19 September 2012 (accessed on 20 September 2012).

Further reading

- Clean Tech Nation: How the U.S. Can Lead in the New Global Economy (2012) by Ron Pernick and Clint Wilder

- Deploying Renewables 2011 (2011) by the International Energy Agency

- Reinventing Fire: Bold Business Solutions for the New Energy Era (2011) by Amory Lovins

- Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation (2011) by the IPCC

- Solar Energy Perspectives (2011) by the International Energy Agency