Energy operator

In quantum mechanics, energy is defined in terms of the energy operator, acting on the wavefunction of the system.

Definition

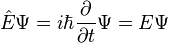

It is given by:[1]

It acts on the wavefunction (the probability amplitude for different configurations of the system)

Application

The energy operator corresponds to the full energy of a system. The Schrödinger equation describes the space- and time-dependence of slow changing (non-relativistic) wavefunction of quantum systems. The solution of this equation for bound system is discrete (a set of permitted states, each characterized by an energy level) which results in the concept of quanta.

Schrödinger equation

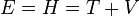

Using the classical equation for conservation of energy of a particle:

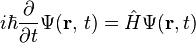

where E = total energy, H = hamiltonian, T = kinetic energy and V = potential energy of the particle, substituting the energy and Hamiltonian operators and multiplying by the wavefunction obtains the Schrödinger equation

that is

where i is the imaginary unit, ħ is the reduced Planck constant, and  is the Hamiltonian operator.

is the Hamiltonian operator.

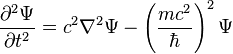

Klein–Gordon equation

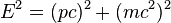

The relativistic mass-energy relation:

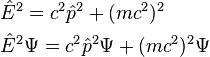

where again E = total energy, p = total 3-momentum of the particle, m = invariant mass, and c = speed of light, can similarly yield the Klein–Gordon equation:

that is:

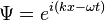

Derivation

The energy operator is easily derived from using the free particle wavefunction (plane wave solution to Schrödinger's equation).[2] Starting in one dimension the wavefunction is

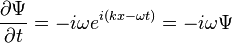

The time derivative of Ψ is

.

.

By the De Broglie relation:

,

,

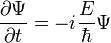

we have

.

.

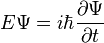

Re-arranging the equation leads to

,

,

where the energy factor E is a scalar value, the energy the particle has and the value that is measured. Cancellation of Ψ leads to

The partial derivative is a linear operator so this expression is the operator for energy:

.

.

It can be concluded that the scalar E is the eigenvalue of the operator, while  is the operator. Summarizing these results:

is the operator. Summarizing these results:

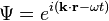

For a 3-d plane wave

the derivation is exactly identical, as no change is made to the term including time and therefore the time derivative. Since the operator is linear, they are valid for any linear combination of plane waves, and so they can act on any wavefunction without affecting the properties of the wavefunction or operators. Hence this must be true for any wavefunction. It turns out to work even in relativistic quantum mechanics, such as the Klein–Gordon equation above.

See also

- Planck constant

- Schrödinger equation

- Momentum operator

- Hamiltonian (quantum mechanics)

- Conservation of energy

- Complex number

- Stationary state

References

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||