Encephalitis

| Encephalitis | |

|---|---|

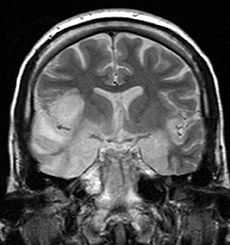

Coronal T2-weighted MR image shows high signal in the temporal lobes including hippocampal formations and parahippocampal gyrae, insulae, and right inferior frontal gyrus. A brain biopsy was performed and the histology was consistent with encephalitis. PCR was repeated on the biopsy specimen and was positive for HSV | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | A83-A86, B94.1, G05 |

| ICD-9 | 323 |

| DiseasesDB | 22543 |

| MedlinePlus | 001415 |

| eMedicine | emerg/163 |

| MeSH | D004660 |

Encephalitis (from Ancient Greek ἐγκέφαλος, enképhalos “brain”,[1] composed of ἐν, en, “in” and κεφαλή, kephalé, “head”, and the medical suffix -itis “inflammation”) is an acute inflammation of the brain. Encephalitis with meningitis is known as meningoencephalitis. Symptoms include headache, fever, confusion, drowsiness, and fatigue. More advanced and serious symptoms include seizures or convulsions, tremors, hallucinations, stroke, hemorrhaging, and memory problems.

In 2013 encephalitis was estimated to have resulted in 77,000 deaths down from 92,000 in 1990.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Adult patients with encephalitis present with acute onset of fever, headache, confusion, and sometimes seizures. Younger children or infants may present irritability, poor appetite and fever.[3] Neurological examinations usually reveal a drowsy or confused patient. Stiff neck, due to the irritation of the meninges covering the brain, indicates that the patient has either meningitis or meningoencephalitis.

Cause

Viral

Viral encephalitis can occur either as a direct effect of an acute infection, or as one of the sequelae of a latent infection. The most common causes of acute viral encephalitis are rabies virus, Herpes simplex, poliovirus, measles virus,[4] varicella zoster virus, and JC virus. Other causes include infection by flaviviruses such as Japanese encephalitis virus, St. Louis encephalitis virus or West Nile virus, or by Togaviridae such as Eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEE virus), Western equine encephalitis virus (WEE virus) or Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEE virus), variola minor virus and variola major virus. Henipaviruses; Hendra (HeV) and Nipah (NiV),[5] are also known to cause viral encephalitis.

Bacterial and other

It can be caused by a bacterial infection, such as bacterial meningitis, spreading directly to the brain (primary encephalitis), or may be a complication of a current infectious disease syphilis (secondary encephalitis). Certain parasitic or protozoal infestations, such as toxoplasmosis, malaria, or primary amoebic meningoencephalitis, can also cause encephalitis in people with compromised immune systems. Lyme disease and/or Bartonella henselae may also cause encephalitis. Cryptococcus neoformans is notorious for causing fungal encephalitis in the immunocompromised. Streptococci, Staphylococci and certain Gram-negative bacilli cause cerebritis prior to the formation of a brain abscess.

Limbic system encephalitis

In a large number of cases, called limbic encephalitis, the pathogens responsible for encephalitis attack primarily the limbic system (a collection of structures at the base of the brain responsible for emotions and many other basic functions).

Autoimmune encephalitis

It has recently been recognised that there are types of encephalitis resulting from an attack of the brain by the body's immune system. These autoimmune conditions include but are not limited to VGKC antibody associated encephalitis, Anti-GAD antibody associated encephalitis, NMDA receptor antibody associated encephalitis, and Hashimoto's encephalitis.

The majority of patients with autoimmune encephalitis do not harbor a tumor and the etiology of the disease in these patients is less clear, often leading to a delayed diagnosis.

Encephalitis lethargica

Encephalitis lethargica is an atypical form of encephalitis which caused an epidemic from 1918 to 1930. Those who survived sank into a semi-conscious state that lasted for decades. Neurologist Oliver Sacks used the Parkinson's drug L-DOPA to revive those still alive in the late 1960s.

There have been only a small number of isolated cases in the years since, though in recent years a few patients have shown very similar symptoms. The cause is now thought to be either a bacterial agent or an autoimmune response following infection.

Diagnosis

Examination of the cerebrospinal fluid obtained by a lumbar puncture procedure usually reveals increased amounts of protein and white blood cells with normal glucose, though in a significant percentage of patients, the cerebrospinal fluid may be normal. CT scan often is not helpful, as cerebral abscess is uncommon. Cerebral abscess is more common in patients with meningitis than encephalitis. Bleeding is also uncommon except in patients with herpes simplex type 1 encephalitis. Magnetic resonance imaging offers better resolution. In patients with herpes simplex encephalitis, electroencephalograph may show sharp waves in one or both of the temporal lobes. Lumbar puncture procedure is performed only after the possibility of prominent brain swelling is excluded by a CT scan examination. Diagnosis is often made with detection of antibodies in the cerebrospinal fluid against a specific viral agent (such as herpes simplex virus) or by polymerase chain reaction that amplifies the RNA or DNA of the virus responsible (such as varicella zoster virus). Serological tests may show high antibody titre against the causative antigen.

Treatment

Treatment is usually symptomatic. Reliably tested specific antiviral agents are few in number (e.g. acyclovir for herpes simplex virus) and are used with limited success in treatment of viral infection, with the exception of herpes simplex encephalitis. In patients who are very sick, supportive treatment, such as mechanical ventilation, is equally important. Corticosteroids (e.g., methylprednisolone) are used to reduce brain swelling and inflammation. Sedatives may be needed for irritability or restlessness. For Mycoplasma infection, parenteral tetracycline is given. Encephalitis due to Toxoplasma is treated by giving a combination of pyrimethamine and sulphadimidine.

Prevention

Vaccination is available against tick-borne[6] and Japanese encephalitis[7] and should be considered for at-risk individuals.

Post-infectious encephalomyelitis complicating small pox vaccination is avoidable as small pox is now eradicated. Contraindication to Pertussis immunisation should be observed in patients with encephalitis. An immunodeficient patient who has had contact with chicken pox virus should be given prophylaxis with hyperimmune zoster immunoglobulin.

Epidemiology

The incidence of acute encephalitis in Western countries is 7.4 cases per 100,000 population per year. In tropical countries, the incidence is 6.34 per 100,000 per year.[8] In 2013 encephalitis was estimated to have resulted in 77,000 deaths down from 92,000 in 1990.[2]

Herpes simplex encephalitis has an incidence of 2–4 per million population per year.[9]

See also

- Rasmussen's encephalitis

- Bickerstaff's encephalitis

- La Crosse encephalitis

- Wernicke's encephalopathy

- Meningitis

- Cerebritis

- Encephalomyelitis - a group of conditions where encephalitis occurs together with spinal cord inflammation

References

- ↑ "Woodhouse's English-Greek Dictionary" (in German). The University of Chicago Library. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.". Lancet 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ↑ "Symptoms of encephalitis". NHS. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ↑ Fisher, D. L.; Defres, S.; Solomon, T. (2015). "Measles-induced encephalitis". QJM 108 (3): 177–182. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcu113. PMID 24865261.

- ↑ Chadha, Mandeep; Comer, J. A. Lowe, L. Rota, P. A. Rollin, P. E. Bellini, W. J. Ksiazek, T. G. Mishra, A. (2006-02-24). "Nipah Virus-associated Encephalitis Outbreak, Siliguri, India". Emerg Infect Dis 12 (2): 235–40. doi:10.3201/eid1202.051247. PMC 3373078. PMID 16494748.

- ↑ "Tick-borne Encephalitis". Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ↑ "Japanese encephalitis". Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ↑ Jmor, F; Emsley HC, Fischer M et al. (October 2008). "The incidence of acute encephalitis syndrome in Western industrialised and tropical countries" (PDF). Virology Journal 5 (134): 134. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-5-134. PMC 2583971. PMID 18973679.

- ↑ Rozenberg, F; Deback C; Agut H (June 2011). "Herpes simplex encephalitis: from virus to therapy". Infectious Disorders Drug Targets 11 (3): 235–250. doi:10.2174/187152611795768088. PMID 21488834.

External links

- The Encephalitis Society - A Global resource on Encephalitis

- Autoimmune Encephalitis Alliance

- WHO: Viral Encephalitis

- Encephalitis Global Inc. - A USA charity sharing information and support

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||