Emmeline

Emmeline, The Orphan of the Castle is the first novel written by English writer Charlotte Turner Smith; it was published in 1788. A Cinderella story in which the heroine stands outside the traditional economic structures of English society and ends up wealthy and happy, the novel is a fantasy. At the same time, it criticises the traditional marriage arrangements of the 18th century, which allowed women little choice and prioritised the needs of the family. Smith's criticisms of marriage stemmed from her personal experience and several of the secondary characters are thinly veiled depictions of her family, a technique which both intrigued and repelled contemporary readers.

Emmeline comments on the 18th-century novel tradition, presenting reinterpretations of scenes from famous earlier works, such as Samuel Richardson's Clarissa (1747–48). Moreover, the novel extends and develops the tradition of Gothic fiction. In combination with this, Smith's style marks her as an early Romantic. Her characters learn about their identities from nature and her landscape descriptions are imbued with political messages about gender relations.

Smith had separated from her husband in 1787 and was forced to write to support herself and her children. She quickly began writing novels, which were profitable at the time. Emmeline was published a year later in 1788; the first edition sold out quickly. Smith's novel was so successful that her publisher paid her more than he had initially promised. The novel was printed in the United States, translated into French, and issued several times during the 19th century.

Composition

Smith and her husband had a tumultuous relationship and in April 1787, after twenty-two years of marriage, she left him. She wrote that she might "have been contented to reside in the same house with him", had not "his temper been so capricious and often so cruel" that her "life was not safe".[1] Her father-in-law had settled money on her children and she expected to receive the money within a year of the separation, thinking she would have to support her children for only a year or so. She never received the money during her lifetime, however, and was forced to write until her death in 1806.[2] To support her ten living children, she had to produce many works and quickly. She wrote almost every day and once works were sent to the printer, they were rarely revised or corrected. Lorraine Fletcher notes in her introduction to the Broadview Press of Emmeline, "there were times when she did not know how a novel would finish even when she was well into the last volume", however outright errors were "rare".[3]

Plot summary

Emmeline is set in Pembroke, Wales and centres around the eponymous heroine. Her parents are both dead and she has been supported by her father's brother, Lord Montreville, at Mowbray Castle. It is suggested at the beginning of the novel that Emmeline's parents were not married when she was born, making her illegitimate; on these grounds, Lord Montreville has claimed Mowbray Castle for himself and his family. Emmeline has been left to be raised by servants, but through reading, she has become educated and accomplished and catches the eye of Lord Montreville's son, Lord Delamere. Delamere falls in love with her and proposes but Emmeline refuses him because his father does not approve and she feels only sisterly affection for him. To escape Delamere's protestations of love, Emmeline leaves Mowbray Castle and lives first with Mrs. Stafford and then Mrs. Ashwood, where Delamere continues to pursue her. Emmeline also rejects the suits of other rich men, confounding the people around her.

The Croft family, lawyers who are trying to rise in society, have influence over and control Lord Montreville. The younger Croft son secretly marries the eldest Montreville daughter to secure a fortune—a most unfortunate match from Lord Montreville's perspective.

Delamere abducts Emmeline: he attempts to take her to Scotland and to force her to marry him. However, after falling ill of a fever, she convinces him to abandon his plans. When Delamere’s mother, Lady Montreville, becomes ill, he is compelled to visit his family. To help her recover, he promises not to see Emmeline for a year. If, after that period, he still loves her, his parents promise to allow him to marry her and she reluctantly agrees.

Emmeline becomes friends with Augusta, Delamere’s sister. Augusta marries Lord Westhaven, who by happenstance, is the brother of Emmeline’s new acquaintance in the country—Adelina. Adelina left her dissipated husband for a lover who abandoned her with a child. She is so distraught that when she sees her brother, Lord Westhaven, she fears his chastisement so much that she briefly goes insane. Emmeline nurses her and her baby; while doing so, she meets Adelina's other brother, Godolphin.

The Crofts circulate rumours of Emmeline’s infidelity to Delamere and when he visits her and sees her with Adelina’s child, he assumes the child is hers and abandons her. Emmeline then travels to France with Mrs. Stafford and Augusta, where she discovers her parents were actually married and that she deserves to inherit Mowbray Castle. Lord Montreville hands the estate over to her, after discovering he was duped by the Crofts. Delamere becomes ill upon discovering that Emmeline was never unfaithful to him. She nurses him, but refuses to marry him. His mother dies in her anxiety over his condition and he dies fighting a duel over his sister’s lover. In the end, Emmeline marries Godolphin.

Themes

Marriage

Emmeline criticises the traditional marriage arrangements of the 18th century, which allowed women little choice and prioritised the needs of the family.[4] Mrs. Stafford, for example, is married quite young to a man with whom she has little in common; only her love for her children keeps her in the marriage (children legally belonged to their father at this time). She has the opportunity to take a lover, but she rejects this option.[5] The novel’s plot reveals the consequences for a woman who does choose this route. Adelina, who was also married young and is unhappy, accepts a lover (the same one Mrs. Stafford rejects). As Fletcher explains, the doubling of the two characters invites a comparison and “in keeping with the increasingly liberal tone of the time the narrator allows Adelina to be happy in the end.”[6] The doubling also “suggest[s] that 'good' and 'bad' women have more in common that some readers were prepared to accept in 1788”.[7] Unlike in most 18th-century novels, the "fallen" woman does not die. As punishment, Adelina goes mad, but she is rewarded in the end—her husband dies and she remarries a man who makes her happy.[8]

Property

Because Emmeline is thought to be illegitimate, she stands outside the official social structure for most of the novel. She must often choose between a family she claims as her own (the Montrevilles) and her own desires. As Fletcher explains, “she embodies a fantasy that has often engaged novel readers, the fantasy that a young woman can win devoted love and overcome all difficulties by her personal qualities alone, without the help of family or dowry.”[9] In writing a version of the Cinderella fairy tale, Smith highlights the disjunction between the fantasy and the 18th-century reality that women without property had little worth in English society.[10]

Autobiography

Through the Staffords, Smith draws a picture of her marriage. Throughout her career, beginning with Elegiac Sonnets (1784), Smith represented her own personal struggles in her works. In the Staffords, she showed a "responsible wife and devoted mother, who attempts to avert her husband's disgrace".[11] In a direct parallel to Smith's own life, Mrs. Stafford must deal with her husband's creditors after which the family flees to France. Adelina also resembles elements of Smith's history, particularly the unhappy marriage that is forced on her early in life by her family. In Emmeline Smith begins a pattern of using secondary heroines to tell her story. Readers who knew her story, which she made public, could identify with her personally. As Fletcher explains, "she shrewdly promoted her career, gained sympathy for her problems as a single mother and turned herself into a celebrity through self-revelation."[12] Initially readers found this technique fascinating and persuasive, but over the years, they came to agree with poet Anna Seward:[13]"I have always been told that Mrs. Smith designed, nay that she acknowledges, the characters of Mr. and Mrs. Stafford to be drawn for herself and her husband. Whatever may be Mr. Smith's faults, surely it was as wrong as indelicate, to hold up the man, whose name she bears, the father of her children, to public contempt in a novel."[14]

Duelling

Smith explores femininity through her portrayal of marriage of property and masculinity through duelling. She compares and contrasts different forms of duelling through five different male characters.[15] Mr. Elkerton is terrified of fighting in a duel; he remains part of the commercial class, failing to achieve the respectability of a gentleman. The elder Croft brother, also part of the commercial class, fails to challenge his wife's lover to a duel. In these characters, Smith demonstrates her "contempt for the commercial class".[16] However, she also criticises "aristocratic recklessnes and self-indulgence" in the characters of Delamere and de Bellozane—both fight duels intending to kill their opponents.[17] It is the hero Godolphin who navigates a middle way. He threatens a duel but is dissuaded from carrying it out by the women in the story.[18]

Genre

Eighteenth-century novel

Smith's novel comments on the development of the genre during the 18th century. For example, usually the heroine marries the first man she thinks of as a possible husband in the novel, but this is not the case in Emmeline. Emmeline marries Godolphin, a character who does not appear until half-way through the narrative. Some readers felt that this was dangerous, since it suggested that the ideal woman would have a romantic past.[19] Smith also rewrites earlier scenes from best-selling novels, offering her own interpretation of them. For example, “Delamere's half-tricking, half-forcing Emmeline into a waiting coach” mirrors a scene from Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa (1747–48). However, unlike Richardson's tale, Smith's does not end tragically but rather with Delamere succumbing to Emmeline's wishes and returning her safe to her home.[20]

Cinderella story

The structure of Emmeline follows the Cinderella pattern: the poor, social outcast becomes rich and socially acceptable. This easy plot resolution, which was expected by readers at the time, was unconvincing to some, such as novelist Walter Scott; others have argued that the ending was meant to feel false and thus force readers to attend to the injustices outlined earlier in the novel.[21]

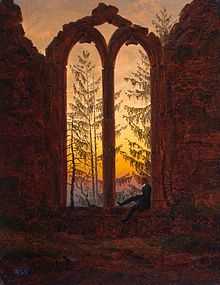

Gothic novel

The castle is a metaphor for Emmeline's body: Delamere wants to possess both. When he first encounters Emmeline, he attempts to rape her, breaking into her room. She escapes through the winding staircases of the Gothic castle, mimicking a scene in Horace Walpole's Gothic novel The Castle of Otranto (1764). Darker elements of the Gothic appear in the Adelina plot line, as she descends into madness and fears violence from those surrounding her.[22]

Style

_by_Edward_Francisco_Burney.jpg)

Smith's novels were praised for their descriptions of landscapes, a technique new to the novel in the late eighteenth century.[24] In Emmeline, the heroine's identity is formed by her encounters with nature, necessitating intricate descriptions of the heroine's mind and surrounding nature.[25] Smith's descriptions were particularly literary, drawing on Thomas Gray's Memoirs of the Life and Writing of Mr. Gray (1775), William Gilpin's Observations on the River Wye (1782), and Edmund Burke's A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757). For example, Emmeline observes that the storm she sees from the Isle of Wight, has "grandeur [which] gratified her taste for the sublime", indicating a Burkean view of nature. In the scene, Godolphin, a naval officer, assumes authority and rescues a foundering party. Burke had associated the sublime with masculinity and the beautiful with femininity; Smith follows him here and indicates to the reader, via the setting, that Godolphin is the hero.[26] However, Smith challenges these strict gender conventions, for example, when she has Emmeline decide to care for Adelina and disregard the social risk involved.[27] Smith describes nature precisely, accurately listing flowers and trees, but she also adds "an emotional and political colouring". As Fletcher explains, "To be in Nature is to recognise, to learn and ultimately to choose. Her protagonists must look at the forms of nature to find themselves. In this sense Smith is an early Romantic".[28]

Publication and reception

Emmeline was published in four volumes by Thomas Cadell in April 1788 and sold for twelve shillings.[29] The first edition of 1500 copies sold out quickly and a corrected second edition was quickly issued. The novel was so successful that Cadell paid her more than he had promised, altogether 200 guineas.[30] Four additional editions were published before the end of the 18th century and five during the 19th century. The novel was translated into French, with six editions of L’Orpheline du Chateau appearing before 1801. There was also a Philadelphia edition in 1802. The novel was not reprinted in the 20th century until Oxford University Press’s 1971 edition.[31]

In general, the novel was "warmly received" and "the reviewers were mainly complimentary".[32] The Critical Review compared it favourably with Frances Burney's Cecilia, particularly the detail of its characterisation.[33] The Monthly Review praised it generally, saying "the whole is conducted with a considerable degree of art; that the characters are natural, and well discriminated: that the fable is uncommonly interesting; and that the moral is forcible and just".[34] Mary Wollstonecraft, who reviewed the novel anonymously for the Analytical Review did not agree with the majority of reviewers, however. She "lamented" "that the false expectations these wild scenes excite, tend to debauch the mind, and throw an insipid kind of uniformity over the moderate and rational prospects of life, consequently adventures are sought for and created, when duties are neglected, and content despised." However, she did single out the virtuous character of Mrs. Stafford for praise.[35]

Notes

- ↑ Qtd. in Blank.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 31.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 31.

- ↑ Fletcher, “Introduction”, 12–13.

- ↑ Fletcher, “Introduction”, 13.

- ↑ Fletcher, “Introduction”, 13.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 14.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 14.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 15.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 15.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 31.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 32–33

- ↑ Blank

- ↑ Qtd. in Fletcher, "Introduction", 32.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 19–20.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 20.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 21.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 20.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 16.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 17.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 17.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 23.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 16.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 23.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 24.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 25–26.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 26.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 27.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 9.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Introduction", 9.

- ↑ Fletcher, "A Note on the Text", 41.

- ↑ Fletcher, "Appendix A", 477.

- ↑ Appendix A, The Critical Review, 477-78.

- ↑ Appendix A, The Monthly Review, 480-81.

- ↑ Appendix A, The Analytical Review, 478-80.

Bibliography

- "Appendix A: The Reception of Emmeline". Emmeline. Ed. Lorraine Fletcher. Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2003. ISBN 1-55111-359-7.

- Blank, Antje. "Charlotte Smith" (subscription only). The Literary Encyclopedia. 23 June 2003. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- Fletcher, Lorraine. "Introduction", "A Note on the Text", and "Appendix A". Emmeline. Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2003. ISBN 1-55111-359-7.

- Klekar, Cynthia. “The Obligations of Form: Social Practice in Charlotte Smith’s Emmeline.” Philological Quarterly 86, no. 3 (2007): 269–89.

External links

- Volume 1 (Third edition) at Google Books

- Volume 2 (Third edition) at Google Books

- Volume 3 (Third edition) at Google Books

- Volume 4 (Third edition) at Google Books