Emergency response (museum)

Emergency response in a museum refers to the measures and decisions needed to prepare for and respond to museum-specific emergencies. Certain action steps are taken to mitigate building, exhibition, and artifact damage, as well as any life loss. While there are prescribed methods for museum emergency response, ultimately each cultural institution should customize and periodically re-evaluate their disaster response and salvage plan to meet available resources and personnel abilities.

Types of disasters and emergencies

Emergencies that can be specific and, in some cases, catastrophic to museums include natural, man-made, and cultural disasters.

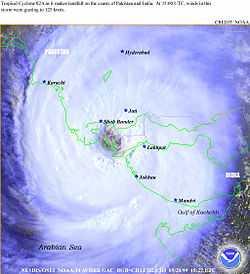

- Hurricane

- Tornado

- Flood

- Heat wave/blizzard

- Pests (insects or otherwise)

- Fire (internal, wildfire, electrical)

- Leak (water or chemical)

- Landslide

- Volcano eruption

- Earthquake

- Terrorism

- Protest/War

- Theft/Vandalism

Preparedness

As with any disaster or emergency, damage or loss can be mitigated through proper and maintained preparation. On some level, emergency preparedness should dovetail collections care practices in every institution.[1]

Building an emergency plan

An emergency plan focuses on identifying any risks and outlining the policies and procedures to be used in disaster response and salvage at a museum.[2] A conservator-restorer, collection manager, or other members of the collections and curation departments are responsible for the physical and intellectual care for the museum and its precious contents – both the artifacts and visitors - and therefore work with the design and management departments to draft an emergency plan. Aside from being a critical element of accreditation, a museum’s emergency plan must identify and anticipate any building, collections, or exhibition risks by outlining steps to mitigation, control, and salvage in the event of an emergency. In addition to the artifacts and exhibitions, as a public institution, a museum is also responsible for the safety of its visitors and employees. Various forms of training exercises and documentation can allow museum staff to be prepared to protect both human and artifact life.[3]

Risk assessment

Ideally, museums conduct annual risk assessments of their collections, building, and surrounding community. Does the collection contain any flammable or combustible items? Has the building environment incurred any alterations that would help or hinder an emergency? Is the area historically prone to earthquakes or floods? Have their been continuous efforts to mitigate pest infestation? Even more, has the museum obtained the proper insurance necessary to recover from an emergency?

Insurance

To assist in the risk assessment of a museum, a detailed and flexible insurance policy is required to accommodate a specific or ever-evolving collection. Risks can be mitigated through an insurance policy that specifies the financial protection of previously assessed museum owned and loaned artifact, and any other property significant to the museum’s mission. An ideal policy is a ‘wall to wall’, or ‘all-risk’ coverage for permanent collections, as well as for loaned collections unless specified by in the loan agreement. Agents generally assist a museum in identifying a monetary insurance limit based on the area’s disaster and emergency history, as well as the probably maximum loss (PML) that is large enough to cover the worst-case scenario.[4]

While PML is another ideal policy, many museums can only afford to assess the risk for the probable maximum loss of an individual gallery or storage area, as well as any functions that extend beyond the shipping dock and front doors (i.e. items on loan, out for conservation, or at an off-site educational program). However, in the event an individual artifact is lost or damaged the previously appraised amount or the current market value will be considered during replacement or conservation. Realizing the unique specifications needed for an effective insurance plan, insurance companies such as the Insurance Services Office, Inc. provide standard fine arts museums applications, declarations, and coverages online.[5]

Preventative measures

Although many preventative measures are universal, certain measures can be performed by museum staff members to mitigate extreme damage to the collection, in both storage and exhibition areas.

Building (Storage and Exhibit Galleries) Alterations:

- Automatic shut-off of gas, sewage, electricity, and water lines. In addition, automatic shut-off of main breakers and fuses to prevent back-feed electricity when starting a generator during the response and recovery process.

- An automatic sprinkler system is throughout museum galleries and storage. In a fire situation, only the sprinkler head(s) nearest (exposed to) the fire will open and discharge water onto the fire. In the future, misting or gas sprinklers might be considered for more compartmentalized storage.

- Fire Safety Self- Inspection for Cultural Institutions, along with an accompanied inspection by fire personnel, is conducted every 6 months to ensure proper fire safety by staff and adequate security for fire risks <http://www.archives.gov/preservation/emergency-prep/fire-check-list.pdf>. This includes coordination with both the Design and Handling aspects of exhibitions and storage as to not compromise human and object emergency routes.

- Valuable items are kept in concrete storage to minimize spread of fire or damage. Items are compartmentalized to deter fire and water incursion. Also in concrete basement storage is hanging artwork stored on sliding metal racks. To mitigate flood damage, painting are hung 2 ft. above the track.

- Textiles are kept in one storage room to prevent fire spread. Kept hanging off the ground by 2 feet, in the middle of the room, and covered overhead by other industrial shelves to minimize water damage from sprinklers.[6]

- Furniture is kept off the ground on shelves and palettes. Any objects close to the ceiling are covered in low-density, polyethylene plastic sheeting to prevent any water damage from automatic sprinkler systems.

- HOBO’s or any relative humidity and temperature data loggers with plexi-glass casings are in every storage and exhibition area.

- Increased use of vitrines and plexi-glass covers for objects made of organic materials (leather, rawhide, straw, bone, shell, and ivory), textiles, and documents (including photographs).

- Utilizing quick release systems for mounts to easily move objects in case of damage.

- Use of safe plastics and fabrics for exhibition.[7]

Environmental monitoring occurs on a weekly or monthly routine depending on the exhibition schedule and environmental factors such as an influx of visitors in the summer heat. The following are museum-specific environments that are controlled yet still vulnerable:

- Storage areas are ideally kept between 40 and 60 degrees Fahrenheit with 40-50% relative humidity.[8]

- Exhibition galleries are exposed to light, fluctuating temperatures and humidity, dust, and other incoming particles that can damage the artifacts or exhibition materials. Temperatures normally linger between 64-77 degrees Fahrenheit and interior vitrines stay between 45-55% relative humidity.[8]

- Collections and exhibition departments coordinate to develop and enforce an integrated pest management system. Practicing good housekeeping skills, securing any degenerative props or artifacts on display and in storage, and disposing of pests, waste, or hazards accordingly assist in the mitigation of a pest infestation.[9]

If possible, exhibition galleries, hallways, lobbies, and offices are functionally decorated with hinged-lid benches that contain an Evacu-Trac Emergency Evacuation Chair. In the event of an emergency, elevators are not safe and any disabled staff member or visitor will need to be able to evacuate down the stairs. Strategically placed near exits and spaced along the designated evacuation routes, the collapsible chair has a low handle height, is lightweight, and has a fail-safe brake so that anyone can assist this person.[10]

Resources and personnel

Despite funding or availability of resources, certain action steps are performed and documented within the emergency plan to prepare the staff for disaster. Staff training and communication with surrounding approved services should be a required element. Collections and exhibition personnel fully inventory all collections and upload it to the museum’s Collections Management System. Updates are generally made at least every 72 hours. Duplicate copies of the database reside off-site and in fire-proof cabinets in the Collections, Curation, and Administration departments. Cabinets are also equipped with Disaster Kits containing safety goggles, flashlights with batteries, nitrile, cotton and fireproof gloves, disposable respirator masks, a medical kit, disposable cameras, large and small tarps, heavy packing blankets, hurricane plastic, markers and paper, artifact identification tags, and emergency and insurance personnel information (all of which are retrievable upon re-entry to minimize any rented or bought materials).[11] In order to maintain a working knowledge of emergency planning and preparedness, a notebook and digital file containing the following are kept on- and off-site:

- Most recent collections survey.

- The approved and up to date Emergency Plan for the museum.

- Information regarding emergency response teams, such as responsibilities and initial procedures.

- Location specification of Disaster Kits within the museum. A chart detailing the location, what materials are located there, and if there are any handling instructions or additions needed to perform a task.

- Emergency Plan Exercise Evaluation Forms that document the staff's previous attempts and progress when practicing emergency response procedures.

- List of approved expertise and services; such as other conservators, heating/cooling rental companies, and storage facilities.

Policies and procedures

In an attempt to maintain control of any emergency, the policies and procedures in the emergency plan outlines the individual, team, and contracted services chain of commands, documentation requirements, and salvage priorities. Policies and procedures form from analyzing and discussing the following elements of a potential emergency:

- Research and assessment of potential risks and hazards. This might include a conservation survey of the collection and building conducted by museum collections and conservation staff, or authorized contracted personnel. Rank risks according to likelihood of damage and prepare for the worst-case scenario for all disasters.

- Resource information about approved contracted services, vetted storage facilities, and emergency first-responders (including museum-specific responders). In the event emergency authorities restrict access for any amount of time, a museum should be equipped with some kind of off-site planning and response headquarters. This can be an approved storage unit with attached room for an office, or a neighboring museum.

- Develop collection salvage priorities before they are damaged. Priorities will help guide the museum in pulling together a plan for handling different types of collection materials, as well as towards a partial collections survey. *Include copies of collection incident forms to determine if any damage had already occurred and was not disaster related.

- Identify which staff members are responding to what disaster or emergency and what their initial responsibilities would be.

Once a draft is completed, it is made available for the entire staff to comment on and provide input. To ensure continuous staff training, mock disasters and quizzes are routinely conducted.

Recently, the Northeast Document Conservation Center and the Massachusetts Board of Library Commissioners developed on online template that allows museums to input data that results in a customized disaster response plan called dPlan.

Response

Aside from contingent factors such as the nature of the emergency, any previous mitigation efforts, and available resources, many museums can respond with similar precautions, procedures, and priorities. The best response is executed by following the prescribed emergency response plan, remaining safe and calm, and acting deliberately.

In an effort to make response and salvage more accessible, the National Heritage Preservation has released a free phone application, the Emergency Response and Salvage APP, or ERS.

Notify museum personnel

Immediate action is taken within the first 48 hours to stabilize the environment, assess the damage, and report conditions and recommendations. In the event that any museum staff members are aware of the disaster first, the necessary local or state first-responders should be immediately notified and required to respond. In addition to the museum staff, the following personnel will be contacted and briefed, via email and phone, before or upon re-entry into the museum:

'Museum Associated Personnel'

- Museum insurance company and agents for the building and collections should be contacted immediately with any available information and photographs of the incident.

- Any museum, organization, or private lender with loaned items in exhibition spaces, and possibly storage, will be contacted; specifically any items that are rare, fragile, or flammable, in which damage would be devastating.

- Any museums that have been scheduled to receive any of our objects for exhibitions within the next 6–12 months must be contacted in anticipation of exhibition schedule changes.

- Museum staff emergency response teams should be notified immediately. Anyone who cannot participate must find an alternate, pre-approved staff member to fill their place ASAP.[12]

'Non-museum Personnel' Any pre-approved disaster response and salvage organizations or contracted companies are also made aware early of the possibility of assisting the museum. It is important to initially contact the following before and after the re-entry and damage assessment to ensure necessary and cost effective assistance:

- A media liaison, museum employed or not, to provide a press release disclosing the incident and asking for cooperation to secure the area from visiting patrons. Any tour groups scheduled must be notified.

- Initially contact the 24-hour AIC CERTS service, 202-661-8068, to request a collections emergency response team that will coordinate efforts with first responders, state agencies, county facility workers, vendors and the public to secure assistance for disaster relief.

- Neighboring museums and conservation labs are a great, and often cheap or free, resource for skilled and untrained volunteers, supplies such as HEPA vacuums specifically designed to remove soot and chemical residue from fire extinguishers, and replacement objects for disrupted exhibits.

- Contact service providers for a generator, new security system, drying systems (fans/air pumps), clean water, and freezer services.

- Contact local truck rental company to receive a quote for an additional regional transport vehicle with standard features of climate control, AC, lift gate, possibly secured shelving, and a security system in the event you need more than your own museum vehicles.

- Note: Any contracted service will be required to sign a Disaster Recovery Contract the details the scope and nature of the contracted work, any biddable security measures, any equipment rentals, transport or labor, and terms of contract that are in accordance with the museum’s mission.

Documentation

To determine the level of damage, the staff teams are prepared to systematically assess collections and exhibitions damage and provide remedies that will reduce recovery time. Small museum personnel teams consist of various combinations of registrar (museum), curators, conservators, and exhibition designers and art handlers. The teams are sorted by their involvement in either the type of collections on display or due to their participation on the initial exhibition team. If this is not known at the moment, off-site back-up information might need to be consulted. Each team has a leader that reports to the emergency response ‘project manager’ who is most likely a conservator, collections manager, or head curator. If applicable, an objects and/or textile conservator(s) can start with the exhibition with the most either loaned or vulnerable objects.[13]

Documentation will be taken by all teams to determine the physical and intellectual damage to the collection and exhibitions. No object or collection should be moved by anyone present before proper documentation is conducted.[14] Teams discuss immediate recommendations for the exhibition’s resurrection; such as in-house object replacements, probability of reproducing panels, barriers, and cases, and security systems. Such documentation includes:

- Exhibition gallery structural damage and how it might affect the quality of the artifacts. An Environmental Monitoring Form is used to take relative humidity and temperature measurements every four hours.

- Object information: Accession number, category, description, materials or medium, any credit line, measurements if possible, donor/lending institution information if possible, location within the gallery space, any protective covering or mounting, and most importantly, the condition of the object.

- Also, note any continued interaction with the damaged elements. For example, soot and ash can be removed with a HEPA vacuum and dry sponges, but interaction with water can cause sticky residue that will be hard to remove in the long run. Other signs of deterioration or mold should be documented.

- Any treatment and storage recommendations for the damaged artifacts. Treatment priority is categorized by ‘Urgent’, ‘Serious but Not Urgent’, ‘Treatment for Long Term Preservation’, ‘Treatment for Exhibition’, and ‘Good Condition’. If the artifact is relocated, documentation must be made of how it was packed and moved, and then where its temporary location will be.

- Photographs will be taken by all recovery teams as well as by the staff photographers. Photographers should be utilized by teams to document any extensive or significant damage.

- In addition, detailed notes about how the disaster occurred and how it can be prevented in the future.

Assessment

Communication is key in assessing the damage, identifying any hazardous materials or circumstances, and proceeding with salvage priorities. Therefore, each response team reconvenes to share damage data and recommendations with the director, deputy director, development officer, financial officer, PR/marketing officer, and related staff to determine the appropriate supplies, assistance, and funding needed. Generally, a Rapid Collections Assessment is conducted by each team and then approved by the project leader to use for insurance and to create a salvage priority list and exhibit rehabilitation timeline. Completion of the assessment calls for the re-communication with:

- Museum insurance representatives and risk manager for the collections and building. We may need an on-site evaluation to accompany the collections assessment.

- Specialized services, state and local workers, and neighboring museums to acquire the appropriate equipment and labor needed (museums are a great source for cheap or free archival packing and shipping supplies)

- Lending museums of objects and exhibitions, as well as any institutions we plan to lend to future to divulge any pertinent condition reports.

- Security company to make repairs to the building to ensure worker and collection safety.

Staff teams constantly work to identify any hazardous materials that could hinder the response and recovery process, for both the objects and personnel involved.[15] Teams will receive this list to ensure safe handling and maneuvering when stabilizing the building and collection.

Stabilization

Armed with the documentation such as a Rapid Collections Assessment, and Artifact Salvage and Exhibition Rehabilitation Timelines, teams formulate and implement a plan to stabilize and recover the building, exhibitions, and artifacts. Although safety hazards surrounding material removal and interactions can cause issues, flexibility and periodic re-assessment is essential.[16]

Retrieval and protection

The following precautions should be taken by all involved to minimize personnel injury and collection damage:

- Identify and safely attempt to repair or remove structural hazards to either the collection or personnel.

- Facilities, Security, and Custodial departments coordinate with the Collections teams to determine what debris or damaged items can be cleaned up and what are actual remnants of objects.

- If able to, adjust temperature and relative humidity to prevent mold outbreak, cracking, expanding, or shrinkage.

To further stabilization, teams:

- Leave undamaged items in place if the environment is stable and secure. If not, they must be moved to a secure, and environmentally controlled area; whether in an in-house or contracted conservation labs, or in off-site storage.

- If no part of the building is dry, protect all objects with polyethylene plastic sheeting.

- Give priority to those items on loan when moving objects.

- Isolate any items with mold and handle with extreme care, as to not transfer spores.

- Retrieve all pieces of broken, melted, or singed objects. Depending on size and severity of damage, place pieces in polyethylene bags or acid-free boxes with acid-free tissue or Versapak as a buffer.[16]

- Once again, it is imperative that custodial crews maintain contact with collections teams to determine what they can throw away. Even if an artifact is a total loss, it must be first assessed by a conservator, put up for deaccession by the museum and historical committees, and then the donor must be notified before any disposal.

There are many online resources that specify how to stabilize and continuously care for objects that have been damaged by material and condition. The AIC's new blog, CoOL, archives individual articles on how to salvage artifacts by material, as well as a 'Find a Conservator' page.[17]

Options for funding recovery

All too often enough, finding the funding to recovery can be difficult but addressed in several creative ways. The traditional ‘ask’ from donors is a great start. However, collaborating museum education, curation, public relations, and conservation personnel could launch “Adopt an Artifact”. Groups or individuals gradually sponsor the conservation of any damaged artifacts or exhibits. Appreciations would be made accordingly with an exhibit label or dedication ceremony. Similarly, a “Resurrection” gala could highlight certain artifacts that need to be conserved while raising funds for said artifacts at a one time, give all event. Another option is to increase the museum employee discount for the museum store (if applicable) from 20% to 25%, for example. All of the proceeds from the store can go directly back into the acquisition of items to replace damaged or lost artifacts. Social media has also played a large role in getting the digital community involved in mobilizing recovery efforts.

NDCC Funding Opportunities for conservation and salvage http://www.nedcc.org/free-resources/funding-opportunities/overview

24-hour or after-hour hotline emergency response contacts

- The American Institute for Conservation (AIC) Hotline National Free Emergency Response Assistance for Cultural Organizations – 202.661.8068 and website.[18]

- Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts (CCAHA) Mid-Atlantic 24-hour Emergency Assistance Hotline – 215.688.0719 and website [19]

- Northeast Document Conservation Center 24 hour Disaster Assistance Hotline (Northeastern US) - 978.470.1010

- Lyrasis Disaster Assistance (Southeastern US) – 800.999.8558

- The Conservation Center. Chicago, IL. - (312) 543-1462

See also

- Collection (museum)

- Collections care

- Object conservation

- Preventive conservation

- Conservator-restorer

- Disaster recovery plan

- Disaster recovery

- Digital preservation

- Integrated pest management

References

- ↑ "Preventative Conservation". International Council of Museums-Committee for Conservation. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- ↑ Buck, edited by Rebecca A.; Gilmore, Jean Allman (2010). MRM5 : museum registration methods (5th ed. ed.). Washington, DC: AAM Press, American Association of Museums. p. 360. ISBN 978-1-933253-15-2.

- ↑ Dorge, comp. by Valerie; Jones, Sharon L. (1999). Building an emergency plan a guide for museums and other cultural institutions. Los Angeles, CA: The Getty conservation institute. p. 47. ISBN 0-89236-529-3.

- ↑ Buck, edited by Rebecca A.; Gilmore, Jean Allman (2010). MRM5 : museum registration methods (5th ed. ed.). Washington, DC: AAM Press, American Association of Museums. pp. 351–369. ISBN 978-1-933253-15-2.

- ↑ Malaro, Marie C.; DeAngelis, Ildiko Pogány (2012). A legal primer on managing museum collections (3rd ed. ed.). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books. p. 464. ISBN 978-1-58834-322-2.

- ↑ "National Park Service - Museum Management Program" (PDF). Nps.gov. Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- ↑ "National Park Service - Museum Management Program" (PDF). Nps.gov. Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Staniforth (1992). Thompson, John M.A., ed. Manual of curatorship : a guide to museum practice (2nd ed. ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 236–238. ISBN 0750603518.

- ↑ Bradley (1992). Thompson, John M.A., ed. Manual of curatorship : a guide to museum practice (2nd ed. ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 236–238. ISBN 0750603518.

- ↑ "Garaventa Evacuation Chairs". Evacutrac.com. Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- ↑ "Heritage Emergency National Task Force – Planning and Preparedness Resources". Heritage Preservation. 2001-09-11. Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- ↑ "National Park Service - Museum Management Program" (PDF). Nps.gov. Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- ↑ Dorge, comp. by Valerie; Jones, Sharon L. (1999). Building an emergency plan a guide for museums and other cultural institutions. Los Angeles, CA: The Getty conservation institute. pp. 49–52. ISBN 0-89236-529-3.

- ↑ "Not Found". Nedcc.adobeconnect.com. Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- ↑ "Conserve O Gram : Hazardous Materials in Your Collection" (PDF). Museum-sos.org. August 1998. Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 ‘Emergency Response and Recovery’: Section 6. Buck, R., Gilmore, J., ed. (2010). Museum Registration Methods (5 ed.). Washington, D.C.: The AAM Press. ISBN 978-1-933253-15-2.

- ↑ "Disaster Response and Recovery". Conservation-us.org. Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- ↑ "Aic-Cert". Conservation-us.org. Retrieved 2014-05-25.

- ↑ "Conservation Services". Theconservationcenter.com. Retrieved 2014-05-25.

External links

- Minnesota Historical Society; Emergency Preparedness and Recovery Plan (2007) and Disaster Response and Recovery resources links

- "Connecting to Collections" Discussions, recordings, and articles about emergency preparation and response.

- Where to purchase the Field Guide to Emergency Response by the Heritage Preservation

- National Park Service Conserve-O-Grams short, focused leaflets discussing how to be prepared for an emergency and salvage artifacts by material.

| ||||||||||