Emanuel Litvinoff

| Emanuel Litvinoff | |

|---|---|

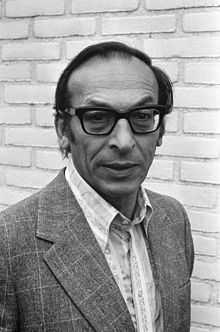

Emanuel Litvinoff in 1973 | |

| Born |

5 May 1915 Bethnal Green, London, England |

| Died |

24 September 2011 (aged 96) Bloomsbury, London, England |

| Residence | London, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Known for | Autobiography, Poetry, Plays, Human Rights |

| Website | |

| http://www.emanuel-litvinoff.com | |

Emanuel Litvinoff (5 May 1915 – 24 September 2011)[1] was a British writer and well-known figure in Anglo-Jewish literature, known for novels, short stories, poetry, plays and human rights campaigning.

Early years

His early years in what he frequently describes as a Jewish ghetto[2] in the East End of London made him very conscious of his Jewish identity, a subject he explored throughout his literary career. Litvinoff was born to Russian Jewish parents who emigrated from Odessa to Whitechapel, London, in 1915. The second of nine children, his father was repatriated to Russia to fight for the czar and never returned, thought to have been killed in the revolution of 1916. One of his brothers was the historian Barnet Litvinoff and his half-brother was David Litvinoff. He left school at fourteen, and after working in a number of unskilled factory jobs, found himself homeless within a year. Drifting between Soho and Fitzrovia in the Depression of the 30s, he wrote since-destroyed hallucinatory materials, and used his wits to survive. Initially a conscientious objector, Litvinoff volunteered for military service in January 1940 on discovering the extent of persecution suffered by Jews in Europe. He was commissioned into the Pioneer Corps in August 1942. Serving in Ulster, West Africa, and the Middle East, he rose through the ranks quickly, promoted to major by the age of 27.

Poetry

Litvinoff became known as a war poet during his time in the army. The 1941 Routledge anthology Poems from the Forces included his work, as did the radio feature of the same name. Conscripts: A Symphonic Declaration appeared in the same year, and in 1942 his first collection, the Untried Soldier, followed. A Crown for Cain published 1948 included his poems from West Africa and Egypt. Over the years, he contributed to many poetry anthologies and periodicals, including The Terrible Rain: War Poets 1939–1945 and Stand magazine, edited by Jon Silkin. He was a friend and mentor of many younger poets. His poetry was collected in 1973's Notes for a Survivor.

To T. S. Eliot

He is also well known for being one of the first to raise publicly the implications of T. S. Eliot's negative references to Jews in a number of poems, a controversy that continues, in his famous poem To T. S. Eliot. This protest against T. S. Eliot on the subject of anti-Semitism took place at an inaugural poetry reading for the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1951. Litvinoff, an admirer of Eliot, was appalled to find Eliot republishing lines he had written in the 1920s about 'money in furs' and the 'protozoic slime' of Bleistein's "lustreless, protrusive eye" only a few years after the Holocaust, in his Selected Poems of 1948. When Litvinoff got up to announce the poem at the ICA reading, the event's host, Sir Herbert Read, declared, "Oh Good, Tom's just come in," referring to Eliot (Thomas Stearns, nickname: Tom). Despite feeling "nervous",[3] Litvinoff decided that "the poem was entitled to be read" and proceeded to recite it to the packed but silent room:

So shall I say it is not eminence chills

lest my people’s bones protest.[4]

but the snigger from behind the covers of history,

the sly words and the cold heart

and footprints made with blood upon a continent?

Let your words

tread lightly on this earth of Europe

In the pandemonium after Litvinoff read the poem, T. S. Eliot reportedly stated, "It's a good poem, it's a very good poem."[5]

Struma

Litvinoff is also known for his poem Struma, written after the Struma disaster. Volunteering for military service in January 1940, Litvinoff saw his membership of the British army as a straightforward matter of combating Nazi evil, but Struma 's sinking in February 1942 complicated this. An old schooner with an unreliable second-hand engine, Struma had left Romania in December 1941 crowded with nearly 800 Jewish refugees escaping the Nazis. After engine failure on the Black Sea she was towed into Istanbul harbour. Her passengers hoped to travel overland to Palestine, but were Turkey forbade them to disembark unless the Britain allowed them to migrate to Palestine. British authorities rejected the refugees' request, and after weeks of deadlock, Turkish authorities towed the Struma back into the Black Sea and set her adrift. The next day, 24 February 1942, she exploded and sank, leaving an estimated 791 dead and only one survivor. It emerged years later that the Struma had been torpedoed by a Soviet submarine. This was unknown at the time, and for Litvinoff the British were responsible. The disaster "blurred the frontiers of evil" in a way that left him reluctant to describe himself as "English" or to seek the kind of assimilation achieved by other Jewish writers in Britain.[6]

The poem contains the lines:

Today my khaki is a badge of shame,

And centuries of years, bowed by my heritage of tears.

Its duty meaningless; my name

Is Moses and I summon plague to Pharaoh.

Today my mantle is Sorrow and O

My crown is Thorn. I sit darkly with the years

Novels

After the war, Litvinoff briefly worked as a ghostwriter for Louis Golding, writing most or all of The Bareknuckle Breed and To the Quayside, before going on to author his own novels. Litvinoff's novels explore the issue of Jewish identity across decades and in a variety of geographical contexts; Britain, Germany, Soviet Russia and Israel.

The Lost Europeans

Ten years after the war, Litvinoff went to live in Berlin. He described it as "a strangely exhilarating experience, like being under fire".[7] The Lost Europeans (1960) was Litvinoff's first novel and was born out of this experience. Set in post-war Berlin, it follows the return of two Jews to Berlin after the Holocaust. One returns for both symbolic and material restitution, the other for revenge on the man who betrayed him.

The Man Next Door

The Man Next Door (1968), described by the New York Times as "the British answer to Portnoy's complaint", tackles British suburban anti-semitism. Set in the fictional Home Counties town of Maidenford, it features a despondent middle-aged vacuum cleaner salesman who sees his new neighbours, wealthy self-made Jews, as the root of his problems, waging an escalating campaign of hatred against them.

Journey Through A Small Planet

Perhaps Litvinoff's best known work is Journey Through a Small Planet (1972), widely regarded today as a masterpiece of Anglo-Jewish literature. In the book Litvinoff chronicled his working class Jewish childhood and early years in the East End of London: a small cluster of streets right next to the city, but which had more in common with the cities of Kiev, Kharkov, and Odessa. Litvinoff describes the overcrowded tenements of Brick Lane and Whitechapel, the smell of pickled herring and onion bread, the rattle of sewing machines and chatter in Yiddish. He also relates stories of his parents, who fled from Russia in 1914, his experiences at school and a brief flirtation with Communism.

The Faces of Terror Trilogy

The celebrated Faces of Terror trilogy followed a pair of young revolutionaries from the streets of East London, and their political passage over the years through to Stalinist Russia. The first novel, A Death Out of Season (1973) was set around the Siege of Sidney Street and the fermenting anarchism of East London. The novel describes youth seduced by revolution, the characters Peter the Painter and Lydia Alexandrova, a young aristocrat who rebels against her class. Blood on the Snow (1975), the sequel, finds Lydia and Peter now committed Bolsheviks, in the chaos of famine and civil war in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution. The final instalment of the trilogy, The Face of Terror (1978), is set during the regime of Stalin, where revolution has turned into repression and the ideals of freedom that Peter and Lydia once had crumbled under guilt and disillusion.

Falls the Shadow

Falls the Shadow (1983) was a controversial novel, written because Litvinoff had become concerned at how he considered Israel to be invoking the memory of the Holocaust to justify its own outrages. Its narrative concerns an apparently distinguished and benign Israeli citizen who is assassinated in the street, then found to have been a concentration camp officer who had escaped using the identity of one of his victims.

Plays

During the 60s and 70s, Litvinoff wrote plays prolifically for television, in particular Armchair Theatre. His play The World In a Room tackled the subject of interracial marriage.

Campaign for Soviet Jewry

Although a successful poet and novelist, the majority of Litvinoff's career was spent spearheading a worldwide campaign for the liberation of Soviet Jewry. In the 1950s, on a rare Western visit to Russia with his first wife, Cherry Marshall, and her fashion show, Litvinoff became aware of the plight of persecuted Soviet Jews, and started a world campaign against this persecution. One of his methods was editing the newsletter Jews in Eastern Europe[8] and also lobbying eminent figures of the twentieth century such as Bertrand Russell, Jean-Paul Sartre, and others to join the campaign. Due to Litvinoff's efforts, prominent Jewish groups in the United States became aware of the issue, and the well-being of Soviet Jews became a worldwide campaign, eventually leading to the mass migration of Jews from the Soviet Union to Israel and the United States.[9] For this he has been described by Meir Rosenne, a former Israeli ambassador to the United States, as "one of the greatest unsung heroes of the twentieth century... who won in the fight against an evil empire" and that "thousands and thousands of Russian Jews owe him their freedom".[10]

Bibliography

- Conscripts (1941)

- The Untried Soldier (1942)

- A Crown for Cain (1948) poems

- The Lost Europeans (1960)

- The Man Next Door (1968)

- Journey Through a Small Planet (1972)

- A Death Out of Season (1973)

- Notes for a Survivor (1973)

- Soviet Anti-Semitism: The Paris Trial (1974)

- Blood on the Snow (1975)

- The Face of Terror (1978)

- The Penguin Book of Jewish Short Stories (1979) editor

- Falls the Shadow (1983)

Notes

- ↑ "Emanuel Litvinoff - 1915-2011". emanuel-litvinoff.com. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ "The Roots of Writing: With Bernard Kops, Emanuel Litvinoff, Harold Pinter, Arnold Wesker; Chair: Melvyn Bragg: Gala Festival Opening Event, In association with the Jewish Quarterly," 2003 Jewish Book Week, jewishbookweek.com (Archive), 1 March 2003, accessed 7 July 2008. (Session transcript.)

- ↑ Hannah Burman, "Emanuel Litvinoff: Full Interview", London's Voices: Voices Online, Museum of London, conducted on 11 March 1998, accessed 7 July 2008.

- ↑ Excerpt from "To T. S. Eliot", in Emanuel Litvinoff, Journey Through A Small Planet (London: Penguin Classics, 2008).

- ↑ As qtd. in Dannie Abse, A Poet in the Family (London: Hutchinson, 1974) 203.

- ↑ Wright, Patrick (2011-10-03). "Emanuel Litvinoff". The Times.

- ↑ Back cover, The Lost Europeans hardback first edition, Vanguard Press 1960.

- ↑ Friedman, M.; Chernin, A.D. (1999). A Second Exodus: The American Movement to Free Soviet Jews. University Press of New England [for] Brandeis University Press. p. 75. ISBN 9780874519136. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ Ro'i, Y. (2003). The Struggle for Soviet Jewish Emigration, 1948-1967. Cambridge University Press. p. 122. ISBN 9780521522441. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ "Emanuel Litvinoff". ultraguest.com. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

Interview with Emanuel Litvinoff, 25 Jun 2011";

References

- Interviews

- Burman, Hannah. "Emanuel Litvinoff: Full Interview". London's Voices: Voices Online. Museum of London. Conducted on 11 March 1998. Accessed 7 July 2008. (Summary and transcript of the interview, covering Litvinoff's life up to the 1950s.)

- "The Roots of Writing: With Bernard Kops, Emanuel Litvinoff, Harold Pinter, Arnold Wesker; Chair: Melvyn Bragg: Gala Festival Opening Event, In association with the Jewish Quarterly". 2003 Jewish Book Week. jewishbookweek.com (Archive), 1 March 2003. Accessed 7 July 2008. (Session transcript and recorded audio clip.)

External links

|