Emancipation of the British West Indies

| Slavery |

|---|

|

|

By country or region

|

|

|

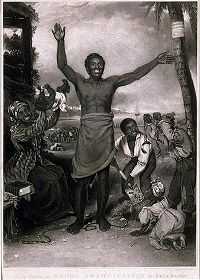

The Emancipation of the British West Indies is the name given to the abolition of slavery in the British colonies of the West Indies. Emancipation of the slaves was proposed as early as 1787, but was not achieved until the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 (effective 1834).

History

The British were the first to attempt to abolish slavery in the Caribbean during the early 19th century, but complete emancipation took time and effort to achieve. Many people, primarily in England, began to view slavery as cruel and unjust as The Enlightenment swept across the nation. The global economic changes taking place during this time period created a decline in the need for slavery in the Caribbean as the industrial revolution and free trade began to take shape and products could be created more cheaply elsewhere. Religious efforts aided in this oppositional movement by taking a strong stance against slavery during the Methodist movement and New Protestant Evangelism. The Roman Catholic Church also played a crucial role in slave uprisings, mainly because it was the primary religion in the area that would recognise slaves as members of the church. Uprisings such as the Haitian Revolution and the Baptist War reinforced the British attempt to abolish slavery by forcing Europeans to focus their attention on Caribbean affairs.

A significant event in the campaign was the preaching by Beilby Porteus, Bishop of London, of the 1783 Anniversary Sermon of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG), an occasion which he used to criticise the Anglican Church’s role in ignoring the plight of the slaves on its Codrington Estates in Barbados, and to recommend means by which the lot of slaves there could be improved.

It was a well-reasoned and much-reprinted sermon, preached before forty members of the society, including eleven bishops of the Church of England. When this largely fell upon deaf ears, Porteus next began work on his Plan for the Effectual Conversion of the Slaves of the Codrington Estate, which he presented to the SPG committee in 1784 and, when it was turned down, again in 1789.

Abolition of the slave trade

As the Abolitionist movement began to gain momentum, a large group of British politicians, businessmen and churchmen, including members of the Clapham Sect, formed the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade and in 1787 petitioned the government for gradual emancipation. At first, they centralised their efforts on the slave trade, but later turned their focus to slavery itself. The first attempts by this group failed, but with each failure more and more people began to support the cause. Uprisings and revolts within the islands perpetuated the situation, and pamphlets were given out describing the horrible conditions which slaves were being subjected to. After years of petitions and demonstrations, the slave trade was finally abolished in 1807 (effective 1808) with the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act.

Emancipation

However, other European countries did not view slavery as negatively as Britain in the early 19th century. Despite British naval support, and treaties with other nations, thousands of slaves were still being illegally imported into the Caribbean, even after 1808. Additional British intervention required registration of all slaves beginning in 1815, but this requirement did little to aid in the cause. With slaves' patience growing thin, and increased uprisings developing within the area, full emancipation became inevitable. 25 years after the slave trade was abolished, slaves in the Caribbean were finally given their freedom through the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833. As of August 1834, all slaves in the British Empire were emancipated, but still indentured to their former owners in an apprenticeship system which was finally abolished in 1838. The apprenticeship system was a system implied to force the ex-slaves to return to the plantation. They were to give 401⁄2 hours free labour and any time after that they were to be paid for their work.

Legacy

Despite the population's freedom from slavery, living conditions on the islands did not improve much over the next several decades. Without a cheap source of labour, sugar cane production declined and economies crumbled. With a growing population, and a decrease in export trade, poverty became widespread. With few sound economic alternatives, many islands turned to the cultivation of bananas, cocoa and acting as offshore banks as an easy source of income in the 20th century.

See also

References

- Emmer, P.C., The Dutch Slave Trade, 1500–1850 Retrieved June 2012

- Kiple, Kenneth F., The Caribbean Slave: A Biological History Retrieved June 2012

- Watkins, Richard Ross, Slavery: Bondage Throughout History Retrieved June 2012