Elizabeth Timothy

| Elizabeth Timothy | |

|---|---|

| Born |

30 June 1702 Amsterdam, Netherlands |

| Died |

3 April 1757 (aged 54) buried 4 April 1757[1] |

Resting place | St. Philip's Anglican Church cemetery, Charleston County, South Carolina, US |

| Residence | Charleston, South Carolina |

| Occupation | printer |

| Known for |

first American female publisher first American female franchise holder |

| Spouse(s) |

Louys Timothée or Lewis Timothy (b.1699) aka Louis Timothee |

| Children |

Peter (b. 24 May 1725) Mary (b. 08 Dec 1726) Louis (b. 19 Jun 1729) Charles (b.14 Sep 1730)[2] Catherine (b. 15 Jan 1735) Louisa (b. 6 Dec 1737) |

| Parent(s) |

Claude Vilain Elizabet Graciot[3] |

| Signature |

|

Elizabeth Timothy or Elisabet Timothee (30 June 1702 – April 1757) was a prominent colonial American printer and newspaper publisher in the colony of South Carolina who worked for Benjamin Franklin. She was the first woman in America to become a newspaper publisher and also the first woman to hold a franchise in America.

Early life

Timothy (maiden name Elizabeth Villin or Elisabet Vilain) was born in Amsterdam on June 30, 1702.[3] Her christening was on 6 July 1702, most likely at the Walloon Church in Amsterdam, as her religion was Waals Hervormd ("Walloon Reformed").[4] She received her formal schooling in the Netherlands, which included accounting.[5] She married Lewis Timothy (French: "Louys Timothee" or "Louis Timothee") in 1724.[6] Her marriage application says she was 22 years old in July 1724.[6]

Timothy's history of becoming a newspaper publisher in America is interwoven with her husband's career. The Timothy family traveled with other French Huguenots from Rotterdam to Philadelphia on the ship Britannia of London in 1731.[5][7][8] The ship's roster shows the Timothy family and their four Dutch children ranging in age from one to six.[9]

Timothy's husband arranged with Benjamin Franklin to revive the South Carolina Gazette weekly newspaper on a six-year franchise contract, dated 26 November 1733. He went to Charleston in the later part of 1733 by himself initially. He started publishing the newspaper on 2 February 1734. Timothy followed later from Philadelphia and went to Charleston in the spring of 1734. She came to Charleston with her six children, four of which were born in the Netherlands.[10]

Mid life

Timothy's husband died on 30 December 1738 of an "unhappy accident".[11] The remaining term on the agreement with Franklin motivated Timothy to become his apprentice and partner.[8] She carried on her late husband's work to fulfill the one year remaining on the Franklin franchise agreement.[12] Timothy's elder son, Peter, "carried on" the newspaper business in name only.[13] Peter was only fourteen years old when he took over his father's printing business, that he was entitled to receive per the Franklin-Timothy agreement of 1733.[14] Since he was just a child in 1738 and too immature to run a business, it was managed by Timothy, Peter's mother.[13] She published the weekly issue of the South-Carolina Gazette starting with January 4, 1739.[13] The masthead said "Printed by Peter Timothy" but was controlled and managed by his mother.[7] Timothy made an announcement in the first issue she edited that she was now publishing the newspaper.[15] This then made her the first female editor and publisher of a newspaper in America.[2][8][10][12][16][17][18]

Timothy, with the aid of her son Peter, increased the quality of the newspaper over the long term, according to the readers of the South-Carolina Gazette.[11][19] Her newspaper was broad-based with not only local news, but colonial news from Boston, Newport, and Philadelphia. She even printed European news from London, Paris, and Constantinople. An important part of her newspaper, that many of her readers looked forward to, was the advertisements. They offered local commodity goods as well as books and stationary supplies. Many times she dedicated at least a full page of her four-page newspaper to advertising.[20]

Timothy's biggest news story was that of the Charleston fire of November 18, 1740. She reported two days later that it destroyed a major portion of the town, including the most valuable commercial buildings and its merchandise worth more than 200,000 pounds sterling.[21] She reported that two-thirds of the town was destroyed including more than 300 houses.[21] In her paper it said "the wind blowing pretty fresh at northwest carried the flakes of fire so far, and by that means set houses on fire at such a distance, that it was not possible to prevent the spreading of it."[22] She credited the diligent citizens of Charleston for their great efforts to extinguish the fire.[21] Her newspaper delivered a proclamation that citizens should render quick and efficient help in extinguishing future fires.[21] She also made a proclamation that citizens should give back stolen items that were taken illegally. In post fire newspaper issues she published business relocations with notices that their customers would be taken care of as usual. She also printed appeals for help in finding lost commodities and assets.[23]

Franklin praised Timothy in saying she was a better business manager and accountant than her late husband had been.[24] He remarked in his Autobiography that while her husband was "a man of learning and honest, but ignorant in matters of account", she on the other hand

not only sent me as clear a state as she could find of the transactions past, but continued to account with the greatest regularity and exactness every quarter afterwards, and managed the business with such success, that she not only brought up reputably a family of children, but, at the expiration of the term, was able to purchase of me the printing-house, and establish her son in it.[11][25][26][26]

Historian Isaiah Thomas remarked that her good business sense could be attributed to her high level of education she acquired in the Netherlands.[27]

Timothy took over her husband's position as the official "public printer" for the colony of South Carolina. She printed acts, laws, and other proceedings for the Assembly of the colony of South Carolina. In addition to publishing the South-Carolina Gazette and government documents pretty much as her late husband did, she printed sermons and religious materials. She also published some 20 historical books and pamphlets between 1739 and 1745.[28] The description of "Printed by Peter Timothy" (her under-aged son) as the printer appeared on each of the publications, however, she made most of the business decisions. [11] Timothy was also the postmaster for Charles Towne, South Carolina and did the postal deliveries of letters, packages, and newspapers.[29]

Later life

After Peter took over the complete printing business in 1746, Timothy opened her own book store. It was next door to the printing office on King Street. She not only carried books, but also stationary, writing supplies such as ink, powder, and quills, as well as tallow, beer, and flour.[29] In a Gazette ad published in October 1746, she announced the availability of books such as pocket Bibles, spellers, and primers. She also sold the books Reflections on Courtship and Marriage, Armstrong's Poem on Health, The Westminster Confession of Faith, Watts' Psalms and Hymns, the Pocket Almanack, and Franklin's works including Poor Richard's Almanack.[30] Timothy ran her book store and stationary shop for about a year and then decided to leave Charleston.[8] Prior to leaving, Timothy advertised in the South-Carolina Gazette that she was leaving the area and wished for people to pay up on debts owed her.[8] She went to a new area for a time and later returned to Charleston in 1756.[8]

Death and will

Timothy wrote her will on 2 April 1757 and died within the month. Her personal effects listed in an inventory were a "parcel of books" that included two French Bibles. The list also showed a marble-covered sideboard, two old desks, and some furniture. Additionally it listed six small items of jewelry, 38 ounces of old silver, some pewter articles, china, and fireplace tools. The value was set at £25 currency for all these items.[31]

Her will stipulated that her widowed daughter Mary Elizabeth Bourquin was to receive a certain small tract of land, a house on King Street, two slaves, and half her clothing and furniture. Her married daughters Catherine Trezevant and Louisa Richards was to receive a house and three slaves and the remainder of the estate.[32]

Personal life and legacy

Timothy belonged to the Charles Towne Library Society, her son Peter being one of the founders.[33] She was a member of St. Philip's Anglican Church in Charleston, South Carolina, with her family.[34] Historians record that Timothy's husband was accidentally killed in December 1738.[34][35] Timothy was pregnant with her seventh child (third American) in 1739, but the child died of premature birth.[36] She also lost two sons in 1739 due to yellow fever.[11][36]

At the time of Timothy's death in 1757 she was survived by her son Peter who had married Ann Donovan. She was also survived by her three daughters: Mary Elizabeth, married to Abraham Bowquin; Catherine, married to Theodore Trezevant; and Louisa, married to James Richards.[31]

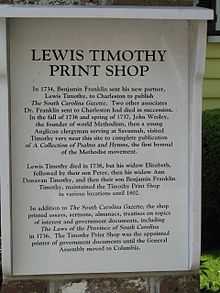

Timothy was inducted into the South Carolina Press Association Hall of Fame in 1973.[37][38] She was inducted into the South Carolina Business Hall of Fame in 2000.[8][37] A plaque is on the bay near Vendue Range in Charleston describing her role in journalism.[39] Timothy was the first known female in American journalism, according to historian A.S. Sallev.[40] The fact that Timothy took over her husband's business of publishing the South-Carolina Gazette newspaper from a franchisee agreement he had with Franklin made her the first female franchisee in America.[41]

Works

The South Carolina Gazette newspaper of 4 January 1739 is a work attributed to Timothy:

-

Containing the freshest Advices Foreign and Domestick

-

bottom part second page

Chief Red Shoes news -

bottom part third page

"Printer of this Gazette" obit -

bottom part fourth page

"Printed by PETER TIMOTHY"

The bottom of the right corner of the third page reads in an obituary of Timothy's husband:

- Whereas the late Printer of this Gazette hath been deprived of his life by an unhappy accident. I take this Opportunity of informing the Public, that I shall contain the said paper as usual; and hope, by the Assistance of my Friends, to make it as entertaining and correct as may be reasonable expected. Wherefore I flatter myself, that all those Persons, who, by Subscription or otherwise, assisted my late Husband, on the prosecution of the Said Undertaking, will be kindly pleased to continue their Favours and good Offices to this poor afflicted Widow and six small children and another hourly expected.

Timothy also published official government documents, examples of which are:

- The Laws of the Province of South Carolina by Nicholas Trott

- Acts Passed by the General Assembly - November 10, 1736 to April 11, 1739

- An Act for the Better Ordering and Governing of Negroes and Other Slaves in This Province (1740)

Timothy also published other materials, examples of which are:

- George Whitefield religious materials.

- Eliza Lucas's articles on growing the indigo plant for dye color.

- Materials on the harsh treatment of slaves.

Franklin reprinted many of Timothy's articles, as did the Gentlemen's Magazine in England.[33]

See also

- Alexander Purdie (publisher)

- William Hunter (publisher)

- William Parks (publisher)

- Joseph Royle (publisher)

- Isaac Collins (printer)

- John Holt (publisher)

- Jane Aitken

Footnotes

- ↑ Eldridge 1997, p. 165.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Sherrow 2002, p. 188.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Historical Records for: Elisabet Vilain". Family Search. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ↑ "Elizabeth birth record". Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Krismann 2005, p. 529.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Family Search – ondertrouw". Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Baker 1977, p. 281.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 "Elizabeth Timothy". Legacy of Leadership. South Carolina Business Hall of Fame. 1999. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ↑ "1731 Britannia". The Palatine Project / ProGenealogists. Ancestry.com. 1999–2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 McKerns 1989, p. 700.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 McKerns 1989, p. 701.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Vaughn 2007, p. 539.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Brigham 1947, pp. 1037–1038.

- ↑ Benjamin Franklin (26 Nov 1733). "Articles of Agreement with Louis Timothée". The Papers of Benjamin Franklin. The American Philosophical Society and Yale University. Retrieved 15 Nov 2013.

- ↑ Schilpp 1983, p. 1.

- ↑ Marzolf 1977, p. 4.

- ↑ Emery 1962, p. 71.

- ↑ "The Family Business: Printing, Publishing, and Journalism in the 18th Century". page 4. National Women's History Museum. 2007. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ↑ Schilpp 1983, p. 4.

- ↑ Schilpp 1983, p. 5.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Schilpp 1983, p. 6.

- ↑ "1740 (November 18) Fire". Preservation Society of Charleston. The South Carolina Historical Society. 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ↑ Schilpp 1983, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Frasca 2006, p. 75.

- ↑ "Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin". Project Gutenberg. May 22, 2008 – updated: November 10, 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2013. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 26.0 26.1 Turner 2008, p. 155.

- ↑ Schilpp 1983, p. 2.

- ↑ Read 1992, p. 446.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 McKerns 1989, p. 702.

- ↑ Perry 2009, p. 22.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Waldrup 1999, p. 126.

- ↑ Eldridge 1997, p. 156.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Waldrup 1999, p. 125.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Turner 2008, p. 157.

- ↑ SALLEY, A. S. (1902). (page 7) "Marriage notices in the South Carolina Gazette, 1732-1801". Internet Archive. Joel Munsell's Sons. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Turner 2008, p. 158.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Sherrow 2002, p. 190.

- ↑ "Timothy, Elizabeth". History Database Search. Facts On File. 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ↑ "Elizabeth Timothy - Charleston, SC - South Carolina Historical Markers". Waymarking.com. Groundspeak, Inc. 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ↑ Wallace 1951, p. 200.

- ↑ "Benjamin Franklin: Father of Franchising?". IFA. International Franchise Association. 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

Bibliography

- Baker, Ira L. (1977). "Elizabeth Timothy – America's First Woman Editor". Journalism Quarterly (Sage Publications) 54.

- Brigham, Clarence Saunders (1947). History and Bibliography of American Newspapers, 1690-1820. American Antiquarian Society.

- Eldridge, Larry D. (1 January 1997). Women and Freedom in Early America. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-2198-8.

- Emery, Edwin (1962). The press and America: an interpretative history of journalism. Prentice-Hall.

- Frasca, Ralph (2006). Benjamin Franklin's Printing Network: Disseminating Virtue in Early America. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-6492-3.

- McKerns, Joseph P. (1989). Biographical Dictionary of American Journalism. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-23819-2.

- Krismann, Carol (2005). Encyclopedia of American Women in Business: M-Z Volume 2 of Encyclopedia of American Women in Business: From Colonial Times to the Present. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 031333384X.

- Marzolf, Marion (1977). Up from the footnote: a history of women journalists. Hastings House. ISBN 0803875029.

- Perry, Lee Davis (2009). Remarkable South Carolina Women. Globe Pequot. ISBN 978-0-7627-4343-8.

- Read, Phyllis J. (1992). The Book of Women's Firsts: Breakthrough Achievements of Almost 1,000 American Women. Random House Information Group. ISBN 978-0-679-40975-5.

- Schilpp, Madelon Golden (1983). Great women of the press. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0809310988.

- Sherrow, Victoria (2002). A to Z of American Women Business Leaders and Entrepreneurs. Facts On File, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-8160-4556-3.

- Turner, Janine (4 March 2008). Holding Her Head High: Inspiration from 12 Single Mothers Who Championed Their Children and Changed History. Thomas Nelson Inc. ISBN 978-1-4185-3762-3.

- Vaughn, Stephen L. (2007). Encyclopedia of American Journalism. CRC Press. ISBN 0203942167.

- Waldrup, Carole Chandler (1 January 1999). Colonial Women: 23 Europeans who Helped Build a Nation. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-5106-7.

- Wallace, David Duncan (1951). South Carolina: A Short History, 1520-1948. University of North Carolina Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to a typical eighteenth century colonial print shop. |