Elisha F. Paxton

| Elisha Franklin Paxton | |

|---|---|

Elisha Franklin Paxton | |

| Nickname(s) | Bull |

| Born |

March 4, 1828 Rockbridge County, Virginia |

| Died |

May 3, 1863 (aged 35) Chancellorsville, Virginia |

| Place of burial | initially buried at Guinea Station, Virginia; reburied at Stonewall Jackson Memorial Cemetery, Lexington, Virginia |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1861–63 |

| Rank |

|

| Commands held | Stonewall Brigade |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Elisha Franklin Paxton (March 4, 1828 – May 3, 1863) was an American lawyer and soldier who served as a general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. He died in combat leading the famed Stonewall Brigade during the Battle of Chancellorsville.

Early life and career

Paxton was born in Rockbridge County, Virginia. He was the son of Elisha Paxton and Margaret McNutt, a Presbyterian family, and his grandfather was American Revolutionary War veteran William Paxton. His first education came from his cousin James H. Paxton's school.[1]

In 1845 he attended Washington College in Lexington, Virginia, and in 1847 he entered Yale University located in New Haven, Connecticut. Paxton then attended the University of Virginia Law School in Charlottesville in 1849,[2] graduating at the top of his class.[3] When fully grown Paxton was described as "five feet ten inches high, heavily built and of great bodily strength",[1] a physique that inspired his childhood nickname, "Bull".[4] He was known not to drink alcohol.[5]

Upon graduating Paxton settled in Virginia and became a lawyer, then a bank president in Lexington.[6] He also later worked as a planter, and then moved to Ohio. After passing the state's bar examination, he worked for several years in Ohio prosecuting land claims.[1] His law practice ended in 1860 because of his failing eyesight, but this did not stop him from becoming prominent in political matters. His son Matthew wrote that "he was a man of ardent temperament and strong convictions such as did not permit him to remain an indifferent spectator of the exciting political occurrences of era." His "blunt and outspoken views" on behalf of the secession of South Carolina caused a rift in his friendship with Lexington resident Thomas J. Jackson; the two men did not speak to each other until after each had joined the Confederate Army.[3]

When he was 26, Paxton married 23 year old Elizabeth Hannah White (died February 16, 1872)[7] on November 2, 1854. She was the daughter of Matthew White and lived in Lexington.[6] They would have four children together, three of whom out-lived Paxton: Matthew W. Paxton, John G. Paxton, and Frank Paxton.[1] The actor Bill Paxton is a direct descendant of Elisha Paxton (great-great-grandson) and his son John Gallatin Paxton.[8] Matthew became the editor of the newspaper Rockbridge County News and John a lawyer in Kansas City, Missouri. Frank lived in San Saba County, Texas.[7]

Civil War service

At the start of the American Civil War in 1861, Paxton chose to follow his home state and the Confederate cause. Despite a lack of any military training, Paxton entered the Confederate Army on April 18 as a first lieutenant of the Rockbridge Rifles, part of Col. James F. Preston's 4th Virginia Infantry Regiment.[2]

The 4th Virginia fought on July 21 during the First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas) in Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Jackson's First Brigade of the Army of the Shenandoah, soon to be known as the Stonewall Brigade. Paxton was wounded in an arm during this battle[2] and his actions won him praise from his comrades.[9] After recovering, Paxton was elected[10] major of the 27th Virginia Infantry on October 14, 1861, but was not re-elected to the position the following spring[1] because of his "heavy-handedness and a lack of tact".[11] On May 30, 1862, Paxton was appointed aide-de-camp to Jackson's staff, and participated in the Valley Campaign of the Shenandoah Valley and the Seven Days Battles, both in Virginia.[2]

By August 4, 1862, Paxton was made Jackson's assistant quartermaster, and fought in the Northern Virginia Campaign. Paxton was appointed assistant adjutant general (chief of staff)[12] on Jackson's staff on August 15, and took part in the Second Battle of Bull Run on August 28–30, and then in the Maryland Campaign and the Battle of Antietam on September 17.[2]

Stonewall Brigade

Col. Andrew J. Grigsby had taken over the Stonewall Brigade when its commander Col. William Baylor was killed at Second Bull Run. At Antietam, the loss of Brig. Gen John R. Jones and Brig. Gen William Starke left Grigsby in charge of an entire division, two command levels above his rank. Despite this, Jackson refused to give him permanent command of anything above regimental level. On November 1, 1862, Paxton was promoted from major to brigadier general and assigned command of the Stonewall Brigade.[13] It was a move that did not sit well with the men he passed over, officers with more experience as well as seniority.[1] Paxton was the choice of Jackson and the posting was made directly by Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Although Jackson rarely deviated from protocol for promotions, his justification for selecting Paxton was that none of the subordinate commanders in the Stonewall Brigade was the "best qualified" for the position because "I did not regard any of them as competent as another."[11] Paxton assumed command of the brigade on November 15.[1] Grigsby was "as mad as thunder" and resigned his commission in protest.[14]

During the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, Paxton and his brigade in the division of Brig. Gen. William B. Taliaferro were on the right of the Confederate defense when Union Maj. Gen. George G. Meade's division made a brief (and unsupported) successful attack, but Paxton's men counterattacked and drove the Federals off.[1] Fredericksburg campaign historian Frank O'Reilly criticized Paxton's performance during the engagement, judging that:

[Paxton] mismanaged the brigade, caused needless casualties by halting under cannon fire, and missed an opportunity to surround and capture two Union regiments. Paxton, because of his inexperience, made numerous mistakes but none so disappointing as misjudging his opponent. ... Paxton wasted important time trying to wheel his brigade into position without first pinning the enemy in place. Consequently, Paxton's Stonewall Brigade barely collided with the Northerners before the Pennsylvanians escape from the trap.[15]

Chancellorsville and death

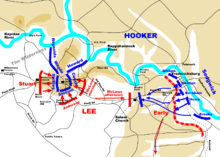

By the spring of 1863, Bull Paxton, who a member of his staff described as a "rather profane and godless man" found new solace in religion, possibly because of his association with the religious Stonewall Jackson. He started carrying a pocket Bible and on the night before the Battle of Chancellorsville, he admitted a premonition of his death and prepared himself for it.[4] On the second day of battle, the brigade was part of Jackson's audacious flanking movement around Union Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker's army. Paxton and his brigade were stationed to guard Germanna Junction on May 2, and that night his men were ordered to the front line.[1]

After Jackson was wounded, command of the Second Corps went briefly to Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill, but when he too was hit, cavalry commander Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart was given command. On May 3 Paxton led his men through densely wooded terrain towards the Union position. He was on foot at the head of his brigade when he was shot through his chest,[1] killing him within an hour.[16] Lt. Randolph Barton of Paxton's staff wrote that Paxton fell only two feet away from him. "I placed my arm under him, when he muttered, 'Tie up my arm', and died. He was not shot in the arm, but through the heart."[4] Later that day army commander Gen. Robert E. Lee sent a wire to the authorities in the Confederate capitol of Richmond, saying:

The enemy was dislodged from all his positions around Chancellorsville and driven back towards the Rappahannock, over which he is now retreating. We have to thank Almighty God for a great victory. I regret to state that Gen'l Paxton was killed, Gen'l Jackson severely and Gen'l [Heth] and D. H. Hill slightly wounded.[7]

Paxton was initially buried at Guinea Station, Virginia, a short distance from where Jackson lay dying. He was later brought back to Lexington and was re-buried there in the Stonewall Jackson Memorial Cemetery, within a few feet of his former commander.[17]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 "Stonewall Hut biography of Paxton". stonewall.hut.ru. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Eicher, p. 420.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Robertson, p. 206.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Sears, p. 330.

- ↑ Stonewall Hut biography of Paxton. "His strength of character was shown by the fact that at this time, when the drinking of whiskey was a universal custom, he abstained altogether from its use, and continued to do so until his death."

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Antietam on the web biography of Paxton". aotw.org. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Paxton Family tree descriptions". ancestry.com. Retrieved 2008-09-17.

- ↑ http://wc.rootsweb.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=PED&db=geolarson3&id=I132494

- ↑ Antietam on the web biography of Paxton. "He was cited for bravery at 1st Manassas for carrying the colors of a Georgia regiment, whose bearer had been shot: '[he] advanced before the regiment, waving his hat, was the first to plant our banner upon their battery.'"

- ↑ During the American Civil War, the enlisted men themselves voted for their officers, electing the regiment's lieutenants, captains, and majors.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Robertson, p. 626.

- ↑ Robertson, p. 590.

- ↑ Wright, p. 96. Appointed from Virginia on November 1, 1862, to rank from that date, and confirmed by Confederate Congress on April 22, 1863.

- ↑ Robertson, p. 627.

- ↑ O'Reilly, pp. 214–15.

- ↑ Paxton Family tree descriptions. May 4, 1863 letter from Henry K. Douglas (Paxton's aide-de-camp) to now widowed Elizabeth Hannah White Paxton. Warner, p. 230: "... he was almost instantly killed by a Minié ball."

- ↑ Warner, p. 230.

References

- Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- O'Reilly, Francis Augustín, The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock, Louisiana State University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-8071-3154-7.

- Robertson, James I., Jr., Stonewall Jackson: The Man, The Soldier, The Legend, MacMillan Publishing, 1997, ISBN 0-02-864685-1.

- Sears, Stephen W., Chancellorsville, Houghton Mifflin, 1996, ISBN 0-395-87744-X.

- Warner, Ezra J., Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders, Louisiana State University Press, 1959, ISBN 0-8071-0823-5.

- Wright, Marcus J., General Officers of the Confederate Army, J. M. Carroll & Co., 1983, ISBN 0-8488-0009-5.

- aotw.org Antietam on the web biography of Paxton.

- stonewall.hut.ru Stonewall Hut biography of Paxton.

- genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com Paxton Family tree descriptions.

- docsouth.unc.edu Paxton's Civil War orders and correspondence.

Further reading

- Morton, Oren F., A History of Rockbridge County, Virginia, McClure Co., 1920.

External links

- Memoir and Memorials: Elisha Franklin Paxton, Brigadier-General, C.S.A.; Composed of his Letters from Camp and Field While an Officer in the Confederate Army, with an Introductory and Connecting Narrative Collected and Arranged by his Son, John Gallatin Paxton. New York: The Neale Publishing Co., 1907.

- www.hmdb.org Paxton's marker stone at Chancellorsville

- Paxton's grave at Find-a-Grave.

|