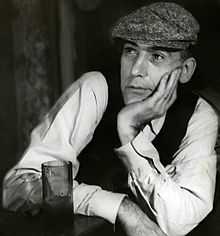

Eli Waldron

Eli Waldron (January 25, 1916 to June 9, 1980) was born Gerald Cleveland Waldron in Oconto Falls, Wisconsin. Waldron was an American writer and journalist whose primary work consisted of short stories, essays, and poetry. His writings were published in literary journals (such as The Kenyon Review, Prairie Schooner, and Story) and popular periodicals (such as Collier's, Holiday, Rolling Stone, Saturday Evening Post, and The New Yorker). Despite his literary achievement, he did not see a book published in his lifetime, nor has one appeared since. Nonetheless, his work continues to gain attention and recognition. In 2013, The Kenyon Review, published his story “Do Birds Like Television?” along with six of his drawings featuring birds. His story, "The Death of Hank Williams" (1955) was included in excerpted form in The Hank Williams Reader issued by Oxford University Press in 2014.

Literary career

Waldron moved to Charlton Street in New York City in 1947 and became part of a literary circle that included Hollis Alpert, Josephine Herbst, S. J. Perelman, and J. D. Salinger. From the 1950s to the 1970s, he contributed stories and essays to The New Yorker magazine and, in the 1960s and 1970s, a number of his poems and experimental fiction works appeared in underground, alternative, and "counter-culture" publications, such as The Illustrated Paper, Rat Subterranean News, Underground, The Village Voice, and The Woodstock Times. Much of Waldron’s fiction and non-fiction reveals a strong interest in the "underdog" and the marginalized, disenfranchised individual, as well as a belief in the possibility of triumph over (often seemingly great) adversity. Making repeated use of satire and often introducing surprise endings, Waldron consistently questioned what he perceived to be the status quo and championed those who may have been viewed as "outsiders" by people in authority or by members of society's "mainstream." This outlook and approach may be seen vividly in such fiction pieces as "The Beekeeper" (published in Prairie Schooner in 1943) and "Zawicki the Chicken" (Cross Section 1945: A Collection of New American Writing), as well as in such non-fiction portraits as "The Death of Hank Williams" (The Reporter, 1955) and "The Lonely Lady of Union Square" (The New Yorker, 1955).

Waldron's first literary efforts in the early 1940s resulted in some critical praise. Esteemed author, Katherine Anne Porter, for example, remarked, in 1943, that Waldron possessed “the spark” and that his work was able to reveal the “deeper stratum of human suffering.” He attracted the attention of New York literary agent, Donald Congdon, who began representing him in 1943, and soon he was considered one of the most promising young writers in the United States. In 1945, he received a literary prize, the “Participation Award,” from the publishing firm, Simon & Schuster for the completion of a novel. His resulting novella, "The Low Dark Road" received strong responses of praise as well as criticism from the firm's editors, and ultimately was not published. He did not rise to the same heights of fame as such contemporaries as James Baldwin, J. D. Salinger, and Herman Wouk. After the demise of his novelistic attempt, he went on to develop his career as a magazine journalist. Despite what writers such as Howard Mitcham and Richard Gehman describe as bouts of writer's block, depression, and alcoholism, he wrote and published until his death in 1980, producing masterful works of literary fiction, striking journalism, irreverent travelogues, satirical flights of fancy, lively verse and even lyrics, as well as drawings. In his 1967 Chicago Tribune article, entitled, "Eli Waldron, Where Are You Now?," Gehman remarked that the suddenly difficult to locate Waldron, who had been part of Gehman's own Greenwich Village literary circle in the 1940s and 1950s, was "one of the best, and perhaps least appreciated, writers of my time." Longtime New Yorker editor, William Shawn, echoed these words in a eulogy for Waldron on November 15, 1980, stating, "What [Waldron] wrote gleamed, and gleams brighter with the passage of time." Shawn also stated, quite simply, that Waldron was "an original, an innovator," and "a writer of immense talent who wrote far too little, perhaps because the standards he set for himself were so high that even he could rarely reach them."

Death

Waldron died in a car crash on Monday, June 9, 1980, on Route 15 a few miles north of Gordonsville and south of Orange, Virginia, while visiting novelist Christian Gehman, the son of author Richard Gehman, a friend from his Greenwich Village days. He was 64 and had been living in Woodstock, N.Y. since 1974 with his wife Marie Waldron. He is survived by daughters Zoe and Eve Waldron from his marriage to painter Phyllis Floyd.

Drawings

Eli Waldron’s drawings, dating from the 1950s to 1980, were less known than his literary work, with only one was published during his lifetime. Nonetheless, they represent an important part of his oeuvre. In these drawings, words and images coalesce to create a literary form of art. Many are captioned and deal with the themes of love, sex, nature, the individual, politics, power, religion, spirituality, and the cosmos with concision, wit, and humor. Motifs include trees, birds, eyes, faces, and signs. A recurrent feature in the drawings is the profile of a long-nosed man, who could be said to represent the artist, observing.

The body of the works include single drawings, groups of related drawings, collections, such as "Varieties of Religious Experience," (undated), and illustrated books, such as "Presto," 1973, that combine drawings with prose or poetry. Some works, such as the collection “Ipglok,” ca. 1973, are “word art,” in which words themselves, in unusual spellings and arrangements, are the subject of the work. Most are in a linear style, favored by Saul Steinberg and Picasso, and are executed in Rapidograph or Flair felt tip pens in drawing pads, 12 x 18 in., 8 1/2 x 11 in. or smaller sheets of paper. He also made paintings on 12 x 16 in. canvas panels. Some of Waldron's correspondence includes his drawings.

Sources

- Bayley, Isabel, selector and editor. Letters of Katherine Anne Porter. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1980.

- Eli Waldron obituary, New York Times, Thursday, June 12, 1980.

- Gehman, Richard. "Eli Waldron, Where are You Now?," Chicago Tribune, "Books Today," Sunday, July 2, 1967.

- Hutchens, John K. "People Who Read and Write," New York Times, "Book Review," March 17, 1946, p. BR13.

- Mitcham, Howard. "Hot Flashbacks and Cool Cookies: Reminiscences of Greenwich Village in the 40's and 50's," Pulpsmith, v. 5 (1985), p. 137-146.

- Shawn, William. Eulogy for Eli Waldron, read at Eli Waldron Memorial, St. Mark's Church in the Bowery, New York City, November 15, 1980.

- Waldron, Eli. Papers. Private collection. New York.

External links

- Abstracts of articles published in The New Yorker at The New Yorker

- Partial bibliography and PDFs of stories at UNZ.org, A Free Website for Periodicals, Books, and Videos at UNZ.org

- Online Exhibition, Eli Waldron--Word Art at POBA Where the Arts Live

- Obituary, The New York Times at The New York Times