Elektra (opera)

| Richard Strauss |

|---|

|

|

Operas

|

Elektra, Op. 58, is a one-act opera by Richard Strauss, to a German-language libretto by Hugo von Hofmannsthal, which he adapted from his 1903 drama Elektra. The opera was the first of many collaborations between Strauss and Hofmannsthal. It was first performed at the Dresden State Opera on January 25, 1909.

Elektra is a difficult, musically complex work which requires great stamina to perform. The role of Elektra, in particular, is one of the most demanding in the dramatic soprano repertoire.

Despite being based on ancient Greek mythology, the opera is highly modernist and expressionist. Hofmannsthal and Strauss's adaptation of the story focuses tightly on Elektra, thoroughly developing her character by single-mindedly expressing her emotions and psychology as she meets with other characters, mostly one at a time. The other characters are Klytaemnestra, Elektra's mother and one of the murderers of Agamemnon; Elektra's father; her sister, Chrysothemis; her brother, Orestes; and Klytaemnestra's lover, Aegisthus. These characters are secondary, and are thus not given much characterization.

Everything else from the myth is minimized as background to Elektra's character and her obsession. Other aspects of the ancient story are completely excluded, tightening the focus on Elektra's furious lust for revenge. The result is a very modern, expressionistic retelling of the ancient Greek myth. Compared to Sophocles's Electra, the opera presents raw, brutal, violent, and bloodthirsty horror.[1]

Performance history

It is regularly performed and, today, the opera is one of the most frequently performed operas based on classical Greek mythology.[2]

Elektra received its UK premiere at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden in 1910 with Edyth Walker in the title role and Sir Thomas Beecham conducting. The first United States performance of the opera in the original German was given by the Philadelphia Grand Opera Company at the Academy of Music, Philadelphia on October 29, 1931 with Anne Roselle in the title role, Charlotte Boerner as Chrysothemis, Margarete Matzenauer as Klytaemnestra, Nelson Eddy as Orest, and Fritz Reiner conducting.

Roles

| Premiere, January 25, 1909 (Conductor: Ernst von Schuch) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Elektra (Electra), Agamemnon's daughter | soprano | Annie Krull |

| Chrysothemis, her sister | soprano | Margarethe Siems |

| Klytaemnestra (Clytemnestra), their mother, Agamemnon's widow | contralto or mezzo-soprano | Ernestine Schumann-Heink |

| Her confidante | soprano | Gertrud Sachse |

| Her trainbearer | soprano | Elisabeth Boehm von Endert |

| A young servant | tenor | Fritz Soot |

| An old servant | bass | Franz Nebuschka |

| Orest (Orestes), son of Agamemnon | baritone | Karl Perron |

| Orest's tutor | bass | Julius Puttlitz |

| Aegisth (Aegisthus), Klytaemnestra's paramour | tenor | Johannes Sembach |

| An overseer | soprano | Riza Eibenschütz |

| First maid | contralto | Franziska Bender-Schäfer |

| Second maid | soprano | Magdalene Seebe |

| Third maid | mezzo-soprano | Irma Tervani |

| Fourth maid | soprano | Anna Zoder |

| Fifth maid | soprano | Minnie Nast |

| Men and women of the household | ||

Synopsis

- Before the opera begins

After the sacrifice of Iphigenia on the ruse that she is to be married, Klytaemnestra has come to hate her husband Agamemnon, who goes off to war against Troy. After his return, with the help of her paramour Aegisth, she murders her husband and now is afraid that her crime will be avenged by her other children, Elektra, Chrysothemis and their banished brother Orest. Elektra has managed to send her brother away while remaining behind to keep her father's memory alive, but all the while, suffering the scorn of her mother and the entire court.

- The action

Five servants try to wash the courtyard of the Palace in Mycenae. While they do their work, they ask where can Elektra be, and she emerges from the shadows with a wild look on her face. The servants continue commenting how she came to be in that state and talk about how they taunt her only to receive insults from her. Only one servant shows mercy for her, but she is taken away by the overseer to be flogged.

Elektra comes back for her daily ritual in memory of her father, who upon his return from Troy was killed while bathing by Klytaemnestra and Aegisth and dragged out into the courtyard. Elektra now starts imagining the day when her father will be avenged and then of the ensuing celebration in which she will lead the triumphal dance.

Chrysothemis leaves the Palace but, unlike Elektra, she is meek and accommodating, and has remained on good terms with Klytaemnestra and Aegisth; she enjoys the privileges that come with being a Princess. She warns her sister that their mother plans to lock Elektra in a tower, but she is rebuffed. Chrysothemis does not wish to go on living a half-death in her own house: she wants to leave, marry and raise children. As loud sounds are heard inside, Elektra mocks her sister that it is her wedding party. In reality, Klytaemnestra has yet again been awakened by her own nightmares of being killed by Orest. Chrysothemis begs Elektra to leave, wishing only to speak to her mother. Followed by her retinue, Klytaemnestra comes to make another sacrifice to appease the gods, but she stops at the sight of Elektra and wishes that she were not there to disturb her. She asks the gods for the reason for her burdens, but Elektra appeases her by telling her mother that she is a goddess herself. Despite the protests of the Trainbearer and Confidante, Klytaemnestra climbs down to talk to Elektra.

Klytaemnestra confides to her daughter that she has been suffering nightmares every night and that she still has not found the way to appease the gods. But, she claims, once that happens, she will be able to sleep again. Elektra teases her mother with little pieces of information about the right victim that must be slain, but she changes the conversation to her brother and why he is not allowed back. To Elektra’s horror, Klytaemnestra says that he has become mad and keeps company with animals. She responds that this is not true and that all the gold that her mother has sent was not being used to support her son but to have him killed.

Then Elektra reveals who is to be the actual victim: it is Klytaemnestra herself. She goes on to describe how the gods must be appeased once and for all. She must be awakened and chased around the house just like an animal that is being hunted. Only when she wishes that all was over and after envying prisoners in their cells, she will come to realize that her prison is her own body. At that time, the axe with which she killed her husband and which will be handed to Orest by Elektra, will fall on her. Only then the dreams will stop. The Trainbearer and Confidante enter and whisper to her.

Klytaemnestra laughs hysterically and, mocking Elektra, leaves. Elektra wonders what has made her mother laugh. Chrysothemis comes to tell her: two messengers have arrived with the news that Orest is dead, trampled by his own horses. As a young servant comes out of the house to fetch the master, he trips over Elektra and Chrysothemis. Elektra does not relent and a terrified Chrysothemis listens as her sister demands that she help her to avenge their father, Elektra goes on to praise her sister and her beauty, promising that Elektra shall be her slave at her bridal chamber in exchange for the assistance in her task. Chrysothemis fights off her sister and flees. Elektra curses her.

Determined to do it alone, she digs for the axe that killed her father, but is interrupted by a mysterious man who comes into the courtyard. She hears that he is expecting to be called from within the Palace because he has a message for the lady of the house. He claims to be a friend of Orest, and says that he was with him at the time of his death. Elektra grieves and the man guesses that she must be a blood relative of Orest and Agamemnon. Then, taken aback, she recognizes him: it is Orest who has come back in disguise. Elektra is initially ecstatic, but also ashamed of what she has become and how she has sacrificed her own royal state for the cause.

Orest’s Tutor comes and interrupts the siblings; their task is dangerous and anything can jeopardize it. The Trainbearer and Confidante come out of the Palace and lead Orest in. A shout is heard from within the Palace, then a grim moan. Elektra smiles brightly, knowing that Orest has killed his mother. Aegisth arrives, he is ecstatic to have heard that Orest is dead and wishes to speak with the messengers. Elektra happily ushers him inside the palace. As Aegisth screams and calls for help, Elektra replies: “Agamemnon can hear you.”

Chrysothemis comes out of the Palace stating that Orest is inside and that he has killed Klytaemnestra and Aegisth. A massacre has begun with Orest’s followers killing those who supported Aegisth and the Queen. Elektra is ecstatic, Chrysothemis goes into the Palace to be with her brother, and Elektra begins to dance. As she reaches the climax of her dance, she falls to the ground: Elektra is dead. Banging on the Palace door, Chrysothemis calls for her brother. There is no answer.

Style and instrumentation

Musically, Elektra deploys dissonance, chromaticism and extremely fluid tonality in a way which recalls but moves beyond the same composer's Salome of 1905, and thus Elektra represents Strauss's furthest advances in modernism, from which he later retreated. The bitonal or extended Elektra chord is a well known dissonance from the opera while harmonic parallelism is also prominent modernist technique.[3]

To support the overwhelming emotional content of the opera, Strauss uses an immense orchestra, with the following instrumentation: woodwind: piccolo (doubling fourth flute, although this is omitted from the instrumentation list at the beginning of the score), 3 flutes (flute 3 doubling piccolo 2), 3 oboes (oboe 3 doubling English horn), heckelphone, clarinet in E-flat, 4 clarinets in B-flat and A, 2 basset horns, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon; brass: 8 horns (horns 5-8 doubling 2 B-flat tenor and 2 F bass Wagner tubas), 6 trumpets, bass trumpet, 2 tenor trombones, bass trombone, contrabass trombone, tuba; percussion: 6-8 timpani (2 players), snare drum, bass drum (with switch), cymbals, tam-tam, triangle, tambourine, castanets, glockenspiel; keyboards: celesta (ad libitum); strings: 2 harps (doubled if possible at the end), 24 violins divided into three groups, 18 Violas divided into three groups (the first of which, unusually, doubles as the fourth violin section), 12 cellos divided into two groups, 8 double basses

Motives and chords

The characters in Elektra are characterized in the music through leitmotifs or chords including the Elektra chord. Klytaemnestra, in contrast to Agamemnon's clearly diatonic minor triad motif, is characterized by a bitonal six note collection most often represented as a pair of two minor chords a tritone apart, typically on B and F, rather than simultaneously.[4]

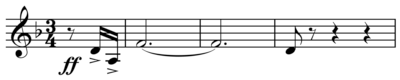

Agamemnon is depicted through a triadic motive:

Recordings

References

Notes

- ↑ Bekker, Paul (1992). "Elektra: A Study by Paul Bekker". In Bryan Randolph Gilliam. Richard Strauss and his world. Princeton University Press. pp. 372–405. ISBN 978-0-691-02762-3. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ↑ Ewans, Michael (2007). "Chapter 5: Elektra". Opera from the Greek: studies in the poetics of appropriation. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-0-7546-6099-6. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ↑ Reisberg, Horace (1975). "The Vertical Dimension in Twentieth-Century Music", Aspects of Twentieth-Century Music, p.333. Wittlich, Gary (ed.). Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-049346-5.

- ↑ Lawrence Kramer, "Fin-de-siècle Fantasies: Elektra, Degeneration and Sexual Science", Cambridge Opera Journal, Vol. 5, No. 2,July 1993, pp. 141-165.

Sources

- Amadeus Almanac

- Elektra Libretto (English)

- Kennedy, Michael, in Holden, Amanda (ed.) (2001), The New Penguin Opera Guide, New York: Penguin Putnam. ISBN 0-14-029312-4

| ||||||||||||||||||||||