El Vallecito

| Kumeyaay Culture – Archaeological Site | ||

Cerro Cuchumá, Kumeyaay refuge area | ||

Kumeyaay coiled basket, woven by Celestine Lachapa, 19th century, San Diego Museum of Man | ||

| Name: | El Cerrito | |

| Type | Mesoamerican archaeology | |

| Location | La Rumorosa, Tecate Municipality, Baja California | |

| Region | Aridoamerica | |

| Coordinates | 32°31′0″N 116°14′53″W / 32.51667°N 116.24806°WCoordinates: 32°31′0″N 116°14′53″W / 32.51667°N 116.24806°W | |

| Culture | Kumeyaay (Spanish:Kumiai) | |

| Language | Kumeyaay | |

| Chronology | 1000 BCE | |

| Period | Prehistory | |

| INAH Web Page | El Vallecito, INAH Web Page | |

El Vallecito is an archaeological site located in the city of La Rumorosa,[1] in the Tecate Municipality, Baja California, Mexico.

It is believed that Baja California had human presence for millions of years, however the available evidence indicates an occupation approximate from 8000 BCE. The sited mentioned sites are more recent, it is estimated that they were developed in the last thousand years, though the engravings, more resistant to erosion, could be older.[2]

The site was inhabited by the Kumeyaay ethnic group whose territory comprised from Santo Tomas, Baja California, to the San Diego coast in California. The eastern region ranged from the Escondido, California, area up to the mountains and deserts in northern Baja California, including the area of Laguna Salada and part of the sierra Juarez known as La Rumorosa.[1]

This site has more than 18 sets of cave painting of which only six may be visited.[1]

The Vallecito is considered one of the most important of the region. There are several important archaeological zones; however, officially not yet been appointed by the responsible authorities.[1]

The site has many cave paintings or petroglyphs made by the ancient peninsula inhabitants. It is known that the territory was occupied by nomadic groups who lived in the region and that they based their existence in hunting and the harvesting of fruits, seeds, roots and sea food.[1]

The decorated rocks with white, black and red figures are pictures made approximately three thousand years ago, when various migratory flows penetrated the Baja California region, known as Yuman or Quechan, which came from what is now the United States.[1]

Other sites

Other sites in the region are:

Cerro del Cuchumá

The area was refuge, hunting, housing and surveillance, of the former Kumeyaay community. It also was an important magical-religious center for rituals and initiation shamanic ceremonies. It represents a very important regional ecosystem known as chaparral sub-mountainous, with beautiful forests (Oaks, Alders and Ficus sycomorus). Its ravines, allows life and refuge of a wildlife variety.

Rancho San José cave painting

The Sierra de San Francisco cave paintings constitute a set of prehispanic murals, characteristic of the “Great Mural” style which flourished in the center of Baja California during pre-Hispanic Aridoamerica. It is likely that the bearers of the great mural style were ancestors of the Cochimí culture, Amerindian people that occupied the region until their extinction in the 19th century, as a consequence of the Spanish conquest.[3]

These paintings are embodied in a large granitic rock (5 × 6 m) and represent diverse human and animal figures, including the figure of a man about 5 m tall with a sort of headdress or hat that resembles horns and a cross on the right hand. This site is located near to the Tecate - La Rumorosa highway.

Piedras Gordas

Area with rock paintings, in several granite stones.

Vallecitos Museum

The Vallecitos Museum is located in about 5 km northwest of la Rumorosa. There is also access from the toll road 5 km before reaching la Rumorosa. There are several sites with petroglyphs and cave paintings geometric, zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figures as well as metates made by the ancient Kumeyaay. The "El Diablito" (Sun Observer), is the figure of a man with a sort of headdress or hat that resembles horns.

Guadalupe Valley

This site has a painting set on a rock, located in front of the El Milagro ranch.[2]

San Vicente Ferrer

South of Ensenada on the trans-peninsular road near San Vicente Ferrer village, is the La Llave ranch, near the San Vicente stream, where a rocky wall rises about 10 meters high, covered with petroglyphs. The designs are all geometric, with a predominance of straight lines. Although their meaning is not understood, they are perhaps the best preserved in northwestern Mexico.[2]

Las Pintas

Las Pinta is located 22 km east of El Rosario de Arriba in the El Malvar ghost town or ejido Abelardo Rodríguez. The area comprises a large set of huge rocks between two hills. On the rocks' surface are hundreds of enigmatic white drawings. This is a beautiful site due to the surrounding desert environment.[2]

San Fernando Velicatá

Located on kilometer 119 km of the trans-peninsular road, south of San Quintín. This is a small, though disperse, group of petroglyphs on the banks of the stream San Fernando. More geometric designs and abstract strokes on an orange tone, and two stone drawings are interesting. A lonely Latin cross and the other a complex composition which seems a sail vessel.[2]

Cataviñá

Cataviñá cave is located 50 km further southeast in the rocky part of the central desert. The site contains magnificent murals. It is a kind of tunnel 3 m long under a colossal hanging rock. The hemispherical roof boasts dozens of scratched triangles, squares and rectangles, concentric circles, and suns as in El Vallecito.[2]

The color variety is astonishing. In just two or three square meters there are black (manganese oxide), ochre (from Hematite (iron oxide)), white (limestone) and yellow and orange.[2]

History

During ancient history, estimated at fourteen thousand years ago, early nomadic group arrived at the peninsula, through the Pacific Ocean shore routes, practising a subsistence economy.

There were three tribal groups perfectly defined during pre-Hispanic times: the Pericúes, Guaycuras and Cochimíes. The Pericúes inhabited the south of the peninsula and extended north, from Cabo San Lucas up to the middle of the peninsula. The Guaycuras inhabited the middle part and the Cochimíes the northern end. In parallel to the Cochimíes there were other nomad groups, such as Kumeyaay (K'miai), one of the native families that together with the Cucapá, Paipai, Kiliwa, Cahilla and Akula, occupied the northern part of Baja California. All belonged to the Yuman group.

The culture

Prehistoric natives were hunter-gatherer nomads. Over time they divided into groups, each of which acquired certain territoriality, where they roamed in search of livelihood provided by natural resources.[4]

Among the initial settlers were the Kumeyaay, who lived from the coast to the mountains. As gatherers, they roamed their territory in search of fruits and seeds, such as acorns, pine nuts and manzanita. These continue to grow in the region and are used as medicinal plants.[4]

Yuman

The Yumans or Quechan, ancestors of regional ethnic groups (Cucapá, Kiliwa, Pai-pai and Kumeyaay) were part of migratory flows to the Baja California peninsula from the north. They occupy a very important place in the displacement process.[1]

- The Cucapá occupied the Mexicali area and the Colorado River delta. They had an incipient agriculture with periodic floods, in addition to hunting and gathering activities.[1]

- The Kiliwa, Pai-pai and Kumeyaay occupied the mountains and Baja California valleys.[1]

Yuman languages

Yuman–Cochimí is a family of languages spoken in Baja California and northern Sonora in Mexico, southern California and western Arizona in the USA.

Cochimí is now extinct.[5] Cucapá is the Spanish name for the Cocopa. Diegueño is the Spanish name for the Ipai/Kumeyaay/Tipai, now often referred to collectively as Kumeyaay. Upland Yuman consists of several mutually intelligible dialects spoken by the politically distinct Yavapai, Hualapai and Havasupai.

Some proposals suggest that the Guaycura languages are part of the Yuman group. The Guaycura languages are a group of several languages spoken in the southern end of the peninsula, currently almost extinct. It is supposed they had some relations with Cchimí; however, there is not enough evidence to confirm this.

Another common proposal, Hokan languages hypothesis, suggests some kind of distant relationship between Yuman languages, a well identified family whose relation is certain with other California languages. While the relationship might be well founded, it is not entirely clear which languages can be considered as part of the supposed Hokan family and which can not.

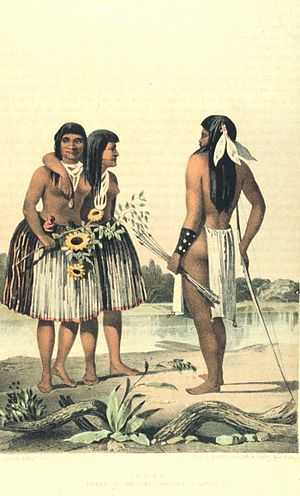

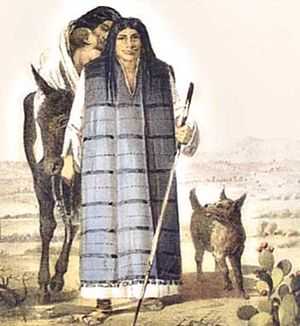

Kumeyaay culture

The Kumeyaay, also known as Tipai-Ipai, Kamia or formerly Diegueño, are Native American people of the extreme southwestern United States and northwest Mexico. They live in the states of California in the US and Baja California in Mexico.In Spanish, the name is commonly spelled Kumiai.

The Kumeyaay consist of two related groups, the Ipai and Tipai. The two coastal groups' traditional homelands were approximately separated by the San Diego River: the northern Ipai (extending from Escondido to Lake Henshaw) and the southern Tipai (including the Laguna Mountains, Ensenada, and Tecate).

The meaning of the term Kumeyaay is unknown, but Ipai or Tipai both mean "people".[6] Some Kumeyaay in the southern areas also refer to themselves as MuttTipi, which means "people of the earth".

Evidence of human settlement in Kumeyaay territory goes back at least 12,000 years.[7] 7000 BCE marked the emergence of two cultural traditions: the California Coast and Valley tradition and the Desert tradition.[8] Historic Tipai-Ipai emerged around 1000 CE;[8] However, others say that Kumeyaay people have lived in San Diego for 12,000 years.[9] At the time of European contact, Kumeyaay comprised several autonomous bands with 30 patrilineal, clans.[6]

Kumeyaay people supported themselves by farming and agricultural wage labor. However, 20-year drought in the mid-20th century crippled the region's dry farming economy.[10] For their common welfare, several reservations formed the non-profit Kumeyaay, Inc.[11]

The Kiliwa, Pai-pai and Kumeyaay occupied the mountains and valleys of Baja California. They used coastal resources and the mountains in the interior of the State, and produced pottery and baskets.[1] They are identified by pottery evidence found and many mortars carved on rock.[1]

Currently, there are Kumeyaay descendants in Mexico living in the mountains. They live in San Jose in Tecate, San Jose de la Zorra and Juntas de Nejí.[4]

Kumeyaay language

Nomenclature and tribal distinctions are not widely agreed upon. The general scholarly consensus recognizes three separate languages: Ipai, Kumeyaay proper (including the Kamia) and Tipai in northern Baja California (e.g., Langdon 1990). However, this notion is not supported by speakers of the language (the actual Kumeyaay people) who contend that within their territory all Kumeyaay (Ipai/Tipai) can understand and speak to each other, at least after a brief acclimatization period.[12] All three languages belong to the Delta–California branch of the Yuman language family, to which several other linguistically distinct but related groups also belong, including the Cocopa, Quechan, Paipai and Kiliwa.

The site

The presence of the Kumeyaay is evidenced by various drawings in walls and ceilings of rock shelters or the exterior walls of stone blocks. These places were used as seasonal camps, lithic workshops or sea shell.[1]

The area is characterized by a diversity of cave painting manifestations. The paintings are made on rock surfaces and are mainly found in rocky shelters. Some of them have mythic-religious meanings.[4]

At this archaeological site more than 30 sets have been found; however only six are exhibited.

Several drawings follow the rock contour. The most common colors are red, in various shades, black and white. The pigments are of mineral origin, pulverized and mixed with some kind of brush.[4]

Petroglyphs

At the archaeological site of El Vallecito, it is only possible to see the following sets at the moment:[1]

- El Tiburón

- El Solsticio or El Diablito

- El Hombre Enraizado

- La Cueva del Indio

- Los Solecitos or Wittinñur y

- El Caracol.

El Tiburón

The “shark” is the first vestige. It is a granite rock, whose exterior resembles the head of a shark. Inside is a figure resembling a flying butterfly in black, surrounded by several mortars carved in rock.[4]

El Solsticio or El Diablito

The “Solstice” or “El Diablito” is perhaps the most important set on the site and possibly depicts a ritual function. This shelter is part of the rock wall, has a diminutive anthropomorphic figure in red with kind of antennas in the head. It is approximately 20 cm and is associated with geometric and anthropomorphic figures in black and white.

It offers an impressive spectacle during 21 and 22 December.[1][4] A sunlight ray penetrates and projects towards the eyes of the figure, illuminating the interior of the shelter for a few minutes. This phenomenon is considered a solstice marker, indicating the start of winter in the northern hemisphere and served to mark a very special date in the Kumeyaay calendar.[1][4]

El Hombre Enraizado

The “rooted man” is a small set of rocks that presents two panels with white figures. In the first pane is a geometrical pattern with five lines ending in circular points. The second panel is a small hollow with an anthropomorphous figure with a trait that seems to be kind of roots or limbs hanging down. It is associated with a few small figures.[1][4]

La Cueva del Indio

The “Indian cave” must have been particularly important for its residents, as it shows a lot of mortars, metates, ceramic material and lithic waste from making tools. It is a great granite dome mushroom with pictorial elements in walls and ceiling, in the north and south sides.[1][4]

The north has a lot of images in red, white and black colors. The most prominent motifs are anthropomorphic figures, concentric circles, lines with rays extending all along the roof and some spots.[1]

The south panel has predominately white motifs, very schematic human figures, some with three heads, circles and other geometric figures. The silhouettes are made with a delineation technique.[1]

Los Solecitos or Wittinñur

In the Kumeyaay language this means "painted rock". Like the previous, it has drawings on the walls and roof.[1] Its meaning is not known.[4]

El Caracol

This set of rocks harmonizes with the landscape and has an important number of red paintings.[1]

Outstanding features are the profusion of elements in the walls and ceiling elaborated in various shades of red and black using natural rock formations. It features small suns (solecitos) made in small hollows-like figures. Part of the set stands out as a rock with more than a dozen mortars and other small depressions or dimples with possible ritual functions, showing some visual balance in the forms displayed.[1]

See also

- Portal del Gobierno de Baja California

- Municipio de Tecate

- Baja California

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 "Pagina INAH el sitio El vallecito" [El Vallecito, site web page]. INAH (in Spanish) (Mexico). Retrieved Sep 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 "El Vallecito, Pinturas Rupestres" [El Vallecito, cave paintings] (in Spanish). Pueblos de Mexico. Retrieved September 2010.

- ↑ In northern Baja California, there is a small native group of people that speak Yuman–Cochimí languages named "Cochimí", although it does not seem they are directly related to the historical Cochimí group at the center of the peninsula. Their language is catalogued as a variety of Kumeyaay language, and they prefer to be called Kumeyaay (Kumiai). Mexico includes the "Cochimí" in the list of ethnic groups.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 4.10 Huante Corrales, Susana. "El Vallecito, principal zona arqueológica de Baja California" [El Vallecito, main archaeological site of Baja California] (in Spanish). Web Siete dias. Retrieved September 2010.

- ↑ It was included among the Hokan languages by Voegelin and Haas, and as Hoka-Sioux, according to Edward Sapir

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Loumala, 592

- ↑ Erlandson et al. 2007, p. 62

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Loumala, 594

- ↑ "Kumeyaay Indians of Southern California". Kumeyaay Information Village. (Retrieved 21 May 2010)

- ↑ Shipek (1978), 611

- ↑ Shipek (1978), 616

- ↑ Smith, 2005

References

- Mithun, Marianne. (1999). The languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23228-7 (hbk); ISBN 0-521-29875-X.

- Leanne Hinton. 1994. Flutes of Fire: Essays on California Indian Languages. Heyday Books, Berkeley, California.

- Langdon, Margaret. 1990. "Diegueño: how many languages?" In Proceedings of the 1990 Hokan–Penutian Languages Workshop, edited by James E. Redden, pp. 184–190. University of Southern Illinois, Carbondale.

- Mithun, Marianne. 1999. The Languages of Native North America. Cambridge University Press.

- Erlandson, Jon M., Torben C. Rick, Terry L. Jones, and Judith F. Porcasi. "One If by Land, Two If by Sea: Who Were the First Californians?" California Prehistory: Colonization, Culture, and Complexity. Eds. Terry L. Jones and Kathryn A. Klar. Lanham, Maryland: AltaMira Press, 2010. 53-62. ISBN 978-0-7591-1960-4.

- Kroeber, A. L. Handbook of the Indians of California. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 78. Washington, DC, 1925.

- Luomala, Katharine. "Tipai-Ipai." Handbook of North American Indians. Volume ed. Robert F. Heizer. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1978. 592-609. ISBN 0-87474-187-4.

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

- Shipek, Florence C. "History of Southern California Mission Indians". Handbook of North American Indians. Volume ed, Heizer, Robert F. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1978. 610-618. ISBN 0-87474-187-4.

- Shipek, Florence C. "The Impact of Europeans upon Kumeyaay Culture". The Impact of European Exploration and Settlement on Location Native Americans. Ed. Raymond Starr. San Diego: Cabrillo Historical Association, 1986: 13-25.

- Smith, Kalim H. 2005. "Language Ideology and Hegemony in the Kumeyaay Nation: Returning the Linguistic Gaze". Master's Thesis, University of California, San Diego.

Further reading

- Du Bois, Constance Goddard. 1904-1906. "'Mythology of the Mission Indians: The Mythology of the Luiseño and Diegueño Indians of Southern California". The Journal of the American Folk-Lore Society, Vol. XVII, No. LXVI. p. 185-8 [1904]; Vol. XIX. No. LXXII pp. 52–60 and LXXIII. pp. 145–64. [1906].

- Langdon, Margaret. 1990. "Diegueño: how many languages?" in Proceedings of the 1990 Hokan–Penutian Languages Workshop, edited by James E. Redden, pp. 184–190. University of Southern Illinois, Carbondale.

External links

- Ethnologue: Yuman

- Kumeyaay Information Village, with educational materials for teachers

- Kumeyaay.com, information website of Larry Banegas, Barona Reservation

- Kumeyaay Indian Language

- Mythology of the Mission Indians, by Du Bois, 1904-1906.

- Religious Practices of the Diegueño Indians, by T.T. Waterman, 1910.

- Kumeyaay (Diegueño) language overview at the Survey of California and Other Indian Languages