ElGamal signature scheme

The ElGamal signature scheme is a digital signature scheme which is based on the difficulty of computing discrete logarithms. It was described by Taher ElGamal in 1984.[1]

The ElGamal signature algorithm described in this article is rarely used in practice. A variant developed at NSA and known as the Digital Signature Algorithm is much more widely used. There are several other variants.[2] The ElGamal signature scheme must not be confused with ElGamal encryption which was also invented by Taher ElGamal.

The ElGamal signature scheme allows a third-party to confirm the authenticity of a message sent over an insecure channel.

System parameters

- Let H be a collision-resistant hash function.

- Let p be a large prime such that computing discrete logarithms modulo p is difficult.

- Let g < p be a randomly chosen generator of the multiplicative group of integers modulo p

.

.

These system parameters may be shared between users.

Key generation

- Randomly choose a secret key x with 1 < x < p − 1.

- Compute y = g x mod p.

- The public key is (p, g, y).

- The secret key is x.

These steps are performed once by the signer.

Signature generation

To sign a message m the signer performs the following steps.

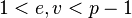

- Choose a random k such that 1 < k < p − 1 and gcd(k, p − 1) = 1.

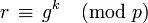

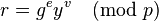

- Compute

.

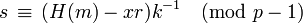

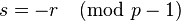

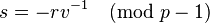

. - Compute

.

. - If

start over again.

start over again.

Then the pair (r,s) is the digital signature of m. The signer repeats these steps for every signature.

Verification

A signature (r,s) of a message m is verified as follows.

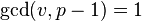

-

and

and  .

. -

The verifier accepts a signature if all conditions are satisfied and rejects it otherwise.

Correctness

The algorithm is correct in the sense that a signature generated with the signing algorithm will always be accepted by the verifier.

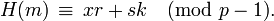

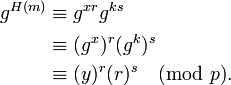

The signature generation implies

Hence Fermat's little theorem implies

Security

A third party can forge signatures either by finding the signer's secret key x or by finding collisions in the hash function  . Both problems are believed to be difficult. However, as of 2011 no tight reduction to a computational hardness assumption is known.

. Both problems are believed to be difficult. However, as of 2011 no tight reduction to a computational hardness assumption is known.

The signer must be careful to choose a different k uniformly at random for each signature and to be certain that k, or even partial information about k, is not leaked. Otherwise, an attacker may be able to deduce the secret key x with reduced difficulty, perhaps enough to allow a practical attack. In particular, if two messages are sent using the same value of k and the same key, then an attacker can compute x directly.[1]

Existential forgery

Original paper[1] did not include hash function as a system parameter. Message m was used directly in the algorithm instead of H(m). It enables an attack called existential forgery, as described in section IV of the paper. Pointcheval and Stern generalized that case and described two levels of forgeries:[3]

- The one-parameter forgery. Let

be a random element. If

be a random element. If  and

and  , the tuple

, the tuple  is a valid signature for the message

is a valid signature for the message  .

. - The two-parameters forgery. Let

and be random elements and

and be random elements and  . If

. If  and

and  , the tuple

, the tuple  is a valid signature for the message

is a valid signature for the message  .

.

Improved version (with a hash) is known as Pointcheval–Stern signature algorithm

See also

- Modular arithmetic

- Digital Signature Algorithm

- Elliptic Curve DSA

- ElGamal encryption

- Schnorr signature

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 T. ElGamal (1985). "A public key cryptosystem and a signature scheme based on discrete logarithms". IEEE Trans inf Theo 31 (4): 469–472. - this article appeared earlier in the proceedings to Crypto '84.

- ↑ K. Nyberg, R. A. Rueppel (1996). "Message recovery for signature schemes based on the discrete logarithm problem". Designs, Codes and Cryptography 7 (1-2): 61–81. doi:10.1007/BF00125076.

- ↑ Pointcheval, David; Stern, Jacques (2000). "Security Arguments for Digital Signatures and Blind Signatures". J Cryptology 13 (3): 361–396.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||