Eigenstate thermalization hypothesis

The Eigenstate Thermalization Hypothesis (or ETH) is a set of ideas which purports to explain when and why an isolated quantum mechanical system can be accurately described using equilibrium statistical mechanics. In particular, it is devoted to understanding how systems which are initially prepared in far-from-equilibrium states can evolve in time to a state which appears to be in thermal equilibrium. The phrase "eigenstate thermalization" was first coined by Mark Srednicki in 1994,[1] after similar ideas had been introduced by Josh Deutsch in 1991.[2] The principal philosophy underlying the eigenstate thermalization hypothesis is that instead of explaining the ergodicity of a thermodynamic system through the mechanism of dynamical chaos, as is done in classical mechanics, one should instead examine the properties of matrix elements of observable quantities in individual energy eigenstates of the system.

Statement of the ETH

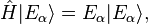

Suppose that we are studying an isolated, quantum mechanical many-body system. In this context, "isolated" refers to the fact that the system has no (or at least negligible) interactions with the environment external to it. If the Hamiltonian of the system is denoted  , then a complete set of basis states for the system is given in terms of the eigenstates of the Hamiltonian,

, then a complete set of basis states for the system is given in terms of the eigenstates of the Hamiltonian,

where  is the eigenstate of the Hamiltonian with eigenvalue

is the eigenstate of the Hamiltonian with eigenvalue . We will refer to these states simply as "energy eigenstates." For simplicity, we will assume that the system has no degeneracy in its energy eigenvalues, and that it is finite in extent, so that the energy eigenvalues form a discrete, non-degenerate spectrum (this is not an unreasonable assumption, since any "real" laboratory system will tend to have sufficient disorder and strong enough interactions as to eliminate almost all degeneracy from the system, and of course will be finite in size[3]). This allows us to label the energy eigenstates in order of increasing energy eigenvalue. Additionally, consider some other quantum-mechanical observable

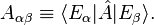

. We will refer to these states simply as "energy eigenstates." For simplicity, we will assume that the system has no degeneracy in its energy eigenvalues, and that it is finite in extent, so that the energy eigenvalues form a discrete, non-degenerate spectrum (this is not an unreasonable assumption, since any "real" laboratory system will tend to have sufficient disorder and strong enough interactions as to eliminate almost all degeneracy from the system, and of course will be finite in size[3]). This allows us to label the energy eigenstates in order of increasing energy eigenvalue. Additionally, consider some other quantum-mechanical observable  , which we wish to make thermal predictions about. The matrix elements of this operator, as expressed in a basis of energy eigenstates, will be denoted by

, which we wish to make thermal predictions about. The matrix elements of this operator, as expressed in a basis of energy eigenstates, will be denoted by

We now imagine that we prepare our system in an initial state for which the expectation value of  is far from its value predicted in a microcanonical ensemble appropriate to the energy scale in question (we assume that our initial state is some superposition of energy eigenstates which are all sufficiently "close" in energy). The Eigenstate Thermalization Hypothesis says that for an arbitrary initial state, the expectation value of

is far from its value predicted in a microcanonical ensemble appropriate to the energy scale in question (we assume that our initial state is some superposition of energy eigenstates which are all sufficiently "close" in energy). The Eigenstate Thermalization Hypothesis says that for an arbitrary initial state, the expectation value of  will ultimately evolve in time to its value predicted by a microcanonical ensemble, and thereafter will exhibit only small fluctuations around that value, provided that the following two conditions are met:[4]

will ultimately evolve in time to its value predicted by a microcanonical ensemble, and thereafter will exhibit only small fluctuations around that value, provided that the following two conditions are met:[4]

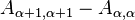

- The diagonal matrix elements

vary smoothly as a function of energy, with the difference between neighboring values,

vary smoothly as a function of energy, with the difference between neighboring values,  , becoming exponentially small in the system size.

, becoming exponentially small in the system size. - The off-diagonal matrix elements

, with

, with  , are much smaller than the diagonal matrix elements, and in particular are themselves exponentially small in the system size.

, are much smaller than the diagonal matrix elements, and in particular are themselves exponentially small in the system size.

Motivation

In statistical mechanics, the microcanonical ensemble is a particular statistical ensemble which is used to make predictions about the outcomes of experiments performed on systems with exactly known energy, which are believed to be in equilibrium. The microcanonical ensemble is based upon the assumption that in thermal equilibrium, all of the microscopic states of an isolated system with the same total energy are equally probable.[5] That is, the system will exist in any one of its given microstates with equal probability. With this assumption, the ensemble average of an observable quantity is found by averaging the value of that observable over all microstates with the correct total energy[5] (for a non-degenerate, discrete quantum mechanical system with some characteristic energy uncertainty ΔE, an appropriate "smearing out" of the averaging process must be performed, in which averages are computed over some appropriate energy window[6]). Alternatively, the canonical ensemble can be employed in situations in which only the average energy of a system is known, and one wishes to find the particular probability distribution for the system's microstates which maximizes the entropy of the system.[5] In either case, one assumes that reasonable physical predictions can be made about a system based on the knowledge of only a small number of physical quantities (energy, particle number, volume, etc.).

These assumptions of ergodicity are well-motivated in classical mechanics as a result of dynamical chaos, since a chaotic system will in general spend equal time in equal areas of its phase space.[5] If we prepare an isolated, chaotic, classical system in some region of its phase space, then as the system is allowed to evolve in time, it will sample its entire phase space, subject only to a small number of conservation laws (such as conservation of total energy). If one can justify the claim that a given physical system is ergodic, then this mechanism will provide an explanation for why statistical mechanics is successful in making accurate predictions. For example, the hard sphere gas has been rigorously proven to be ergodic.[5]

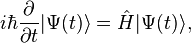

However, this mechanism of dynamical chaos is absent in Quantum Mechanics, due to the strictly linear time evolution of the Schrödinger equation,

where  is the Hamiltonian of the system, and

is the Hamiltonian of the system, and  is its state vector at some arbitrary time

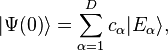

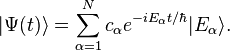

is its state vector at some arbitrary time  . If we expand the state at time zero in a basis of energy eigenstates according to

. If we expand the state at time zero in a basis of energy eigenstates according to

where D is the dimension of the Hilbert space, then the time evolution of the quantum state is given simply by

The expectation value of any observable  at any given time is

at any given time is

This time evolution is manifestly linear, and any notion of dynamical chaos is absent. Thus, it becomes an open question as to whether an isolated quantum mechanical system, prepared in an arbitrary initial state, will approach a state which resembles thermal equilibrium, in which a handful of observables are adequate to make successful predictions about the system. While one may naively expect, on the basis of the linear evolution of the Schrödinger equation, that such a situation is not possible, a variety of experiments in cold atomic gases have indeed observed thermal relaxation in systems which are, to a very good approximation, completely isolated from their environment, and for a wide class of initial states.[4][6] The task of explaining this experimentally observed applicability of equilibrium statistical mechanics to isolated quantum systems is the primary goal of the Eigenstate Thermalization Hypothesis.

Equivalence of the Diagonal and Microcanonical Ensembles

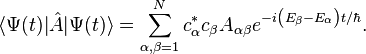

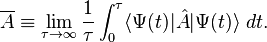

We can define a long-time average of the expectation value of the operator  according to the expression

according to the expression

If we use the explicit expression for the time evolution of this expectation value, we can write

The integration in this expression can be performed explicitly, and the result is

Each of the terms in the second sum will become smaller as the limit is taken to infinity. Assuming that the phase coherence between the different exponential terms in the second sum does not ever become large enough to rival this decay, the second sum will go to zero, and we find that the long-time average of the expectation value is given by[3]

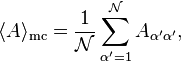

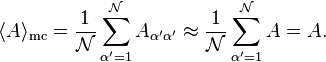

This prediction for the time-average of the observable  is referred to as its predicted value in the diagonal ensemble,[7] The most important aspect of the diagonal ensemble is that it depends explicitly on the initial state of the system, and so would appear to retain all of the information regarding the preparation of the system. In contrast, the predicted value in the microcanonical ensemble is given by the equally-weighted average over all energy eigenstates within some energy window centered around the mean energy of the system[6]

is referred to as its predicted value in the diagonal ensemble,[7] The most important aspect of the diagonal ensemble is that it depends explicitly on the initial state of the system, and so would appear to retain all of the information regarding the preparation of the system. In contrast, the predicted value in the microcanonical ensemble is given by the equally-weighted average over all energy eigenstates within some energy window centered around the mean energy of the system[6]

where  is the number of states in the appropriate energy window, and the prime on the indices indicates that the summation is restricted to this appropriate microcanonical window. This prediction makes absolutely no reference to the initial state of the system, unlike the diagonal ensemble. Because of this, it is not clear why the microcanonical ensemble should provide such an accurate description of the long-time averages of observables in such a wide variety of physical systems.

is the number of states in the appropriate energy window, and the prime on the indices indicates that the summation is restricted to this appropriate microcanonical window. This prediction makes absolutely no reference to the initial state of the system, unlike the diagonal ensemble. Because of this, it is not clear why the microcanonical ensemble should provide such an accurate description of the long-time averages of observables in such a wide variety of physical systems.

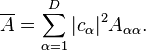

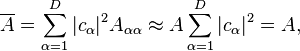

However, suppose that the matrix elements  are effectively constant over the relevant energy window, with fluctuations that are sufficiently small. If this is true, this one constant value A can be effectively pulled out of the sum, and the prediction of the diagonal ensemble is simply equal to this value,

are effectively constant over the relevant energy window, with fluctuations that are sufficiently small. If this is true, this one constant value A can be effectively pulled out of the sum, and the prediction of the diagonal ensemble is simply equal to this value,

where we have assumed that the initial state is normalized appropriately. Likewise, the prediction of the microcanonical ensemble becomes

The two ensembles are therefore in agreement.

This constancy of the values of  over small energy windows is the primary idea underlying the Eigenstate Thermalization Hypothesis. Notice that in particular, it states that the expectation value of

over small energy windows is the primary idea underlying the Eigenstate Thermalization Hypothesis. Notice that in particular, it states that the expectation value of  in a single energy eigenstate is equal to the value predicted by a microcanonical ensemble constructed at that energy scale. This constitutes a foundation for quantum statistical mechanics which is radically different from the one built upon the notions of dynamical ergodicity.[1]

in a single energy eigenstate is equal to the value predicted by a microcanonical ensemble constructed at that energy scale. This constitutes a foundation for quantum statistical mechanics which is radically different from the one built upon the notions of dynamical ergodicity.[1]

Tests of the Eigenstate Thermalization Hypothesis

Several numerical studies of small lattice systems appear to tentatively confirm the predictions of the Eigenstate Thermalization Hypothesis in interacting systems which would be expected to thermalize.[6] Likewise, systems which are integrable tend not to obey the Eigenstate Thermalization Hypothesis.[6]

Some analytical results can also be obtained if one makes certain assumptions about the nature of highly excited energy eigenstates. The original 1994 paper on the ETH by Mark Srednicki studied, in particular, the example of a quantum hard sphere gas in an insulated box. This is a system which is known to exhibit chaos classically,.[1] For states of sufficiently high energy, Berry's conjecture states that energy eigenfunctions in this many-body system of hard sphere particles will appear to behave as superpositions of plane waves, with the plane waves entering the superposition with random phases and Gaussian-distributed amplitudes[1] (the precise notion of this random superposition is clarified in the paper). Under this assumption, one can show that, up to corrections which are negligibly small in the thermodynamic limit, the momentum distribution function for each individual, distinguishable particle is equal to the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution[1]

where  is the particle's momentum, m is the mass of the particles, k is the Boltzmann constant, and the "temperature"

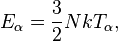

is the particle's momentum, m is the mass of the particles, k is the Boltzmann constant, and the "temperature"  is related to the energy of the eigenstate according to the usual equation of state for an ideal gas,

is related to the energy of the eigenstate according to the usual equation of state for an ideal gas,

where N is the number of particles in the gas. This result is a specific manifestation of the ETH, in that it results in a prediction for the value of an observable in one energy eigenstate which is in agreement with the prediction derived from a microcanonical (or canonical) ensemble. Note that no averaging over initial states whatsoever has been performed, nor has anything resembling the H-theorem been invoked. Additionally, one can also derive the appropriate Bose–Einstein or Fermi–Dirac distributions, if one imposes the appropriate commutation relations for the particles comprising the gas.[1]

Currently, it is not well understood how high the energy of an eigenstate of the hard sphere gas must be in order for it to obey the ETH.[1] A rough criterion is that the average thermal wavelength of each particle be sufficiently smaller than the radius of the hard sphere particles, so that the system can probe the features which result in chaos classically (namely, the fact that the particles have a finite size[1] ). However, it is conceivable that this condition may be able to be relaxed, and perhaps in the thermodynamic limit, energy eigenstates of arbitrarily low energies will satisfy the ETH (aside from the ground state itself, which is required to have certain special properties, for example, the lack of any nodes[1] ).

Alternatives to Eigenstate Thermalization

Two alternative explanations for the thermalizaton of isolated quantum systems are often proposed:[6]

- For initial states of physical interest, the coefficients

exhibit large fluctuations from eigenstate to eigenstate, in a fashion which is completely uncorrelated with the fluctuations of

exhibit large fluctuations from eigenstate to eigenstate, in a fashion which is completely uncorrelated with the fluctuations of  from eigenstate to eigenstate. Because the coefficients and matrix elements are uncorrelated, the summation in the diagonal ensemble is effectively performing an unbiased sampling of the values of

from eigenstate to eigenstate. Because the coefficients and matrix elements are uncorrelated, the summation in the diagonal ensemble is effectively performing an unbiased sampling of the values of  over the appropriate energy window. For a sufficiently large system, this unbiased sampling should result in a value which is close to the true mean of the values of

over the appropriate energy window. For a sufficiently large system, this unbiased sampling should result in a value which is close to the true mean of the values of  over this window, and will effectively reproduce the prediction of the microcanonical ensemble. However, this mechanism may be disfavored for the following heuristic reason. Typically, one is interested in physical situations in which the initial expectation value of

over this window, and will effectively reproduce the prediction of the microcanonical ensemble. However, this mechanism may be disfavored for the following heuristic reason. Typically, one is interested in physical situations in which the initial expectation value of  is far from its equilibrium value. For this to be true, the initial state must contain some sort of specific information about

is far from its equilibrium value. For this to be true, the initial state must contain some sort of specific information about  , and so it becomes suspect whether or not the initial state truly represents an unbiased sampling of the values of

, and so it becomes suspect whether or not the initial state truly represents an unbiased sampling of the values of  over the appropriate energy window. Furthermore, whether or not this were to be true, it still does not provide an answer to the question of when arbitrary initial states will come to equilibrium, if they ever do.

over the appropriate energy window. Furthermore, whether or not this were to be true, it still does not provide an answer to the question of when arbitrary initial states will come to equilibrium, if they ever do. - For initial states of physical interest, the coefficients

are effectively constant, and do not fluctuate at all. In this case, the diagonal ensemble is precisely the same as the microcanonical ensemble, and there is no mystery as to why their predictions are identical. However, this explanation is disfavored for much the same reasons as the first.

are effectively constant, and do not fluctuate at all. In this case, the diagonal ensemble is precisely the same as the microcanonical ensemble, and there is no mystery as to why their predictions are identical. However, this explanation is disfavored for much the same reasons as the first.

Temporal Fluctuations of Expectation Values

The condition that the ETH imposes on the diagonal elements of an observable is responsible for the equality of the predictions of the diagonal and microcanonical ensembles.[3] However, the equality of these long-time averages does not guarantee that the fluctuations in time around this average will be small. That is, the equality of the long-time averages does not ensure that the expectation value of  will settle down to this long-time average value, and then stay there for most times.

will settle down to this long-time average value, and then stay there for most times.

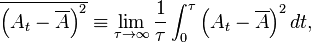

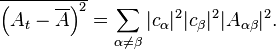

In order to deduce the conditions necessary for the observable's expectation value to exhibit small temporal fluctuations around its time-average, we study the mean squared amplitude of the temporal fluctuations, defined as[3]

where  is a shorthand notation for the expectation value of

is a shorthand notation for the expectation value of  at time t. This expression can be computed explicitly, and one finds that[3]

at time t. This expression can be computed explicitly, and one finds that[3]

Temporal fluctuations about the long-time average will be small so long as the off-diagonal elements satisfy the conditions imposed on them by the ETH, namely that they become exponentially small in the system size.[3][6] Notice that this condition allows for the possibility of isolated resurgence times, in which the phases align coherently in order to produce large fluctuations away from the long-time average.[4] The amount of time the system spends far away from the long-time average is guaranteed to be small so long as the above mean squared amplitude is sufficiently small.[3][4]

Quantum Fluctuations and Thermal Fluctuations

The expectation value of a quantum mechanical observable represents the average value which would be measured after performing repeated measurements on an ensemble of identically prepared quantum states. Therefore, while we have been examining this expectation value as the principle object of interest, it is not clear to what extent this represents physically relevant quantities. As a result of quantum fluctuations, the expectation value of an observable is not typically what will be measured during one experiment on an isolated system. However, it has been shown that for an observable satisfying the ETH, quantum fluctuations in its expectation value will typically be of the same order of magnitude as the thermal fluctuations which would be predicted in a traditional microcanonical ensemble.[3][6] This lends further credence to the idea that the ETH is the underlying mechanism responsible for the thermalization of isolated quantum systems.

General Validity of the ETH

Currently, there is no known analytical derivation of the Eigenstate Thermalization Hypothesis for general interacting systems.[6] However, it has been verified to be true for a wide variety of interacting systems using numerical exact diagonalization techniques, to within the uncertainty of these methods.[4][6] It has also been proven to be true in certain special cases in the semi-classical limit, where the validity of the ETH rests on the validity of Shnirelman's theorem, which states that in a system which is classically chaotic, the expectation value of an operator  in an energy eigenstate is equal to its classical, microcanonical average at the appropriate energy.[8] Whether or not it can be shown to be true more generally in interacting quantum systems remains an open question. It is also known to explicitly fail in certain integrable systems, in which the presence of a large number of constants of motion prevent thermalization.[4]

in an energy eigenstate is equal to its classical, microcanonical average at the appropriate energy.[8] Whether or not it can be shown to be true more generally in interacting quantum systems remains an open question. It is also known to explicitly fail in certain integrable systems, in which the presence of a large number of constants of motion prevent thermalization.[4]

It is also important to note that the ETH makes statements about specific observables on a case by case basis - it does not make any claims about whether every observable in a system will obey ETH. In fact, this certainly cannot be true. Given a basis of energy eigenstates, one can always explicitly construct an operator which violates the ETH, simply by writing down the operator as a matrix in this basis whose elements explicitly do not obey the conditions imposed by the ETH. Conversely, it is always trivially possible to find operators which do satisfy ETH, by writing down a matrix whose elements are specifically chosen to obey ETH. In light of this, one may be led to believe that the ETH is somewhat trivial in its usefulness. However, the important consideration to bear in mind is that these operators thus constructed may not have any physical relevance. While one can construct these matrices, it is not clear that they correspond to observables which could be realistically measured in an experiment, or bear any resemblance to physically interesting quantities. An arbitrary Hermitian operator on the Hilbert space of the system need not correspond to something which is a physically measurable observable.[9]

Typically, the ETH is postulated to hold for "few-body operators,"[4] observables which involve only a small number of particles. Examples of this would include the occupation of a given momentum in a gas of particles,[4][6] or the occupation of a particular site in a lattice system of particles.[6] Notice that while the ETH is typically applied to "simple" few-body operators such as these,[4] these observables need not be local in space[6] - the momentum number operator in the above example does not represent a local quantity.[6]

There has also been considerable interest in the case where isolated, non-integrable quantum systems fail to thermalize, despite the predictions of conventional statistical mechanics. Disordered systems which exhibit many-body localization are candidates for this type of behavior, with the possibility of excited energy eigenstates whose thermodynamic properties more closely resemble those of ground states.[10][11] It remains an open question as to whether a completely isolated, non-integrable system without static disorder can ever fail to thermalize. One intriguing possibility is the realization of "Quantum Disentangled Liquids."[12]

See also

- Equilibrium thermodynamics

- Fluctuation dissipation theorem

- Important Publications in Statistical Mechanics

- Non-equilibrium thermodynamics

- Quantum thermodynamics

- Statistical physics

- Configuration entropy

- Chaos Theory

- Hard spheres

- Quantum statistical mechanics

- Microcanonical Ensemble

- H-theorem

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Mark Srednicki (1994). "Chaos and Quantum Thermalization". Physical Review E 50 (2): 888. arXiv:cond-mat/9403051v2. Bibcode:1994PhRvE..50..888S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.50.888.

- ↑ Deutsch, J.M. (February 1991). "Quantum statistical mechanics in a closed system". Physical Review A 43 (4): 2046–2049. Bibcode:1991PhRvA..43.2046D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.43.2046. PMID 9905246.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Mark Srednicki (1998). "The approach to thermal equilibrium in quantized chaotic systems". Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General 32 (7): 1163. arXiv:cond-mat/9809360. Bibcode:1999JPhA...32.1163S. doi:10.1088/0305-4470/32/7/007.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Marcos Rigol; Srednicki, Mark (2012). "Alternatives to Eigenstate Thermalization". Physical Review Letters 108 (11). arXiv:1108.0928. Bibcode:2012PhRvL.108k0601R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.110601.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Reichl, Linda E. (2009). A Modern Course in Statistical Physics (3rd ed.). Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3527407828.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 Marcos Rigol; Dunjko, Vanja; Olshanii, Maxim (2009). "Thermalization and its mechanism for generic isolated quantum systems". Nature 452 (7189): 854–8. arXiv:0708.1324. Bibcode:2008Natur.452..854R. doi:10.1038/nature06838. PMID 18421349.

- ↑ Amy C. Cassidy; Clark, Charles W.; Rigol, Marcos (2011). "Generalized Thermalization in an Integrable Lattice System". Physical Review Letters 106 (14). arXiv:1008.4794. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.106n0405C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.140405.

- ↑ Sanjay Hortikar; Srednicki, Mark (1997). "Random Matrix Elements and Eigenfunctions in Chaotic Systems". Physical Review E 57 (6): 7313. arXiv:chao-dyn/9711020. Bibcode:1998PhRvE..57.7313H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.57.7313.

- ↑ Ballentine, Leslie E. (1998). Quantum Mechanics: A Modern Development. World Scientific Publishing. ISBN 981-02-4105-4.

- ↑ David A. Huse; Nandkishore, Rahul; Oganesyan, Vadim; Pal, Arijeet; Sondhi, S. L. (2013). "Localization protected quantum order". arXiv:1304.1158. Bibcode:2013PhRvB..88a4206H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.88.014206.

- ↑ D.M. Basko; Aleiner, I.L; Altshuler, B.L (2005). "Metal-insulator transition in a weakly interacting many-electron system with localized single-particle states". arXiv:cond-mat/0506617. Bibcode:2006AnPhy.321.1126B. doi:10.1016/j.aop.2005.11.014.

- ↑ Tarun Grover; Fisher, Matthew P. A. (2013). "Quantum Disentangled Liquids". arXiv:1307.2288.

External links

- "Overview of Eigenstate Thermalization Hypothesis" by Mark Srednicki, UCSB, KITP Program: Quantum Dynamics in Far from Equilibrium Thermally Isolated Systems

- "The Eigenstate Thermalization Hypothesis" by Mark Srednicki, UCSB, KITP Rapid Response Workshop: Black Holes: Complementarity, Fuzz, or Fire?

- "Quantum Disentangled Liquids" by Matthew P. A. Fisher, UCSB, KITP Conference: From the Renormalization Group to Quantum Gravity Celebrating the science of Joe Polchinski

![\overline{A} = \lim_{\tau \to \infty} \frac{1}{\tau}\int_{0}^{\tau}\left [ \sum_{\alpha, \beta=1}^{D}c_{\alpha}^{*}c_{\beta} A_{\alpha \beta} e^{-i \left (E_{\beta} - E_{\alpha} \right )t/\hbar} \right ]~ dt.](../I/m/042f693797587700a087787738aa0733.png)

![\overline{A} = \sum_{\alpha=1}^{D}|c_{\alpha}|^{2}A_{\alpha \alpha} + i \hbar \lim_{\tau \to \infty} \left [ \sum_{\alpha \neq \beta}^{D} \frac{c_{\alpha}^{*}c_{\beta}A_{\alpha \beta}}{E_{\beta}-E_{\alpha}}\left ( \frac{e^{-i \left (E_{\beta} - E_{\alpha} \right )\tau/\hbar}-1}{\tau} \right ) \right ].](../I/m/f62f9067d107947ed363aebdc4ed7024.png)